Terrible Tech 2.0

The Most Burdensome, Anti-Consumer Technology Policy Proposals in Washington

Photo Credit: Getty

Executive Summary

If you are looking for bipartisanship in Washington, D.C., the technology policy sector may be your best bet— but not in a good way. There is a bipartisan impulse to exercise control over the Internet, apps, devices, and the algorithms and artificial intelligence that make them possible. This bipartisan “consensus” seeks to replace the hands-off approach that has been mostly prevalent since the Internet’s inception with one of greater government control.

While regulatory agencies, rather than Congress, do much of the lawmaking these days, Congress has become ambitious about extending its power over the tech sector. This report spells out how dangerous these ambitions are. Executive and independent agencies have their own plans for encroaching on the Internet. The favorability toward expansion of the administrative state by Republicans in particular—under a supposedly deregulatory Trump administration—heightens the urgency, and demands a fresh look.

This report was inspired by an earlier report, “The Digital Dirty Dozen: The Most Destructive High-Tech Legislative Measures of the 107th Congress” by Wayne Crews and Adam Thierer. As was the case with the original “Digital Dirty Dozen” report, the trend toward interventionist policies threatens to lead to legal and regulatory uncertainty for entrepreneurs and potential public harm. That has resulted in new legislation and regulation covering the Internet sector.

To date, a hands-off regulatory approach has helped fuel an explosion in broadband access innovation, and, barring interference from regulators, will allow a 5G Internet to make a large positive impact on the world. But, unfortunately, there are now dozens of proposed technology-related bills in Congress that threaten to expand the government’s reach. Not as paradoxically as it might seem, many big tech companies—seeing their market position as secure and desiring predictability—often support regulation.

This paper highlights numerous categories of interventionist policies, focuses on some of the most destructive legislative offerings within each category, and settles on the ones we consider to be the worst.

These bills address broadband deployment and access, antitrust and competition policy, bias and content controls, child protection, cybersecurity, and more.

Some are retreads, like those on online marketing and privacy. There are measures to increase antitrust intervention and to regulate “biased,” “harmful,” and other forms of speech.

The 115th Congress narrowly modified Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act with respect to human trafficking. Now both parties contemplate something more like a purge of Section 230. Section 230 allows social media networks to moderate their content without being held to the liability standards of a traditional publisher or a speaker. It protects platforms from lawsuits about third-party posts by recognizing that these hosts do not supply content like a newspaper or the content’s creator does. This enables the mostly permissionless, user-driven Internet experience we enjoy online today. Without this safeguard, platforms would have to vet the enormous amount of user-driven content before displaying it because of the increased liability they would assume. This would be prohibitively time-consuming and expensive. Alternatively, and ironically for conservative critics of Section 230, platforms could take a completely hands-off approach to curating content, but the results would likely be too violent, pornographic, or offensive to attract many eyeballs.

There are also attempts to set standards for privacy and online advertising and to address online “addiction” and hold companies accountable for it. Some seek to bring the gig economy into the regulatory maze of labor law. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve and the Securities Exchange Commission may seek to assert their authority over the payments processing sector just as cryptocurrencies are beginning to emerge.

The pressure to regulate has intensified thanks to the emergence of two other powerful regulatory centers that are vying with America to set the gold standard for global technological regulation. While the U.S. has traditionally aimed at empowering technology users, it faces competition from two different models. The European Union aims to protect technology users in paternalistic fashion. China wants to control how people use technology. For a global industry, regulations imposed by jurisdictions that encompass a large percentage of global population and GDP will affect American companies and consumers.

We argue instead for innovation and the separation of technology and state. Policy makers, including Republicans, must pay special attention to how these various proposals would expand invasive administrative bodies like the Federal Trade Commission, the Federal Communications Commission, the Securities and Exchange Commission, and other agencies.

Old-school telecommunications, transportation, and infrastructure have long been highly regulated, with government-supported monopoly in some instances. The Internet still offers an opportunity to show that spontaneous order can work to serve consumers and society better than lawmakers.

Market solutions, unlike legislation, better lend themselves to address the myriad problems that inevitably arise in a free, competitive economy. The Internet was not initially designed as the mass commercial and consumer medium it is today.

There is a role for law. Fraud, falsification, identity theft, hacking, and the like should be punished, but overly burdensome legislation will create legal and regulatory obstacles for small businesses—a reason some large firms favor intervention—and the development of newer technologies and services, which is one of the great hidden costs of regulation.

Bad legislation lays the groundwork for worse legislation later. Embracing regulation and central planning entail embracing collective “solutions” that will be difficult to correct later. The legislation we actually need would be a bill to prevent many of these misguided proposals.

Introduction

If you are looking for bipartisanship in Washington, D.C., the technology policy sector may be your best bet— but not in a good way. There is a bipartisan impulse to exercise control over the Internet, apps, devices, and the algorithms and artificial intelligence that make them possible. This bipartisan “consensus” seeks to replace the hands-off approach that has been mostly prevalent since the Internet’s inception with one of greater government control.1

While regulatory agencies, rather than Congress, do much of the lawmaking these days, Congress has become ambitious about extending its power over the tech sector.2 This report spells out how dangerous these ambitions are. Executive and independent agencies have their own plans for encroaching on the Internet. The favorability toward expansion of the administrative state by Republicans in particular—under a supposedly deregulatory Trump administration3—raises the urgency further, and demands a fresh look.4

This report was inspired by an earlier report, “The Digital Dirty Dozen: The Most Destructive High-Tech Legisla- tive Measures of the 107th Congress” by Wayne Crews and Adam Thierer. As was the case with the original “Digital Dirty Dozen” report, the trend toward interventionist policies threatens to lead to legal and regulatory uncertainty for entrepreneurs and potential public harm. That has resulted in new legislation and regulation covering the Internet sector.

In the recent past, court decisions also have played a role. For example, in 2018 the Supreme Court, reversing precedent, greatly expanded the power of state governments to tax beyond their borders when it gave the go-ahead to the remote taxation of goods purchased online. Of course, there also have been more encouraging court decisions. For example, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals recently upheld the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) repeal of net neutrality regulations.5

To date, a hands-off regulatory approach has helped fuel an explosion in broadband access innovation, and, barring interference from regulators, will allow a 5G Internet to make a large positive impact on the world.

But, unfortunately, there are now dozens of proposed technology-related bills in Congress that threaten to expand the government’s reach.

Meanwhile, tech industry critics complain that we are becoming addicted to our handheld devices and warn that the computer that beat the world champions at the strategic boardgame, Go, will steal our jobs next.6

While the FCC has successfully worked to roll back Obama-era net neutrality rules that would regulate the Internet as a public utility, some of the same Big Tech or FAANG—Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, Google7— companies that pushed for net neutrality rules are facing calls from both the left and right for regulation of online content standards on online platforms. Not as paradoxically as it might seem, many big tech companies—seeing their market position as secure and desiring predictability—often support regulation.

This report highlights numerous categories of interventionist policies, focuses on some of the most destructive legislative offerings within each category, and settles on the ones we consider to be the worst.

These bills address broadband deployment and access, antitrust and competition policy, bias and content controls, child protection, cybersecurity, and more. Some are retreads, like those on online marketing and privacy.8 There are measures to increase antitrust intervention and to regulate “biased,” “harmful,” and other forms of speech. Many of these proposals center on “reform” of the “sixteen words that created the Internet.”9

As Box 1 shows, the 115th Congress narrowly modified Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act with respect to human trafficking.10 Now both parties contemplate something more like a purge of Section 230.11

Section 230 allows social media networks to moderate their content without being held to the liability standards of a traditional publisher or a speaker.12 It protects platforms from lawsuits about third-party posts by recognizing that these hosts do not supply this content like a newspaper or the content’s creator. This enables the mostly permissionless, user-driven Internet experience we enjoy online today.

Section 230 applies even if a platform has content standards and acts to remove materials in violation of those rules. Without this safeguard, platforms would have to vet the enormous amount of user-driven content before displaying it because of the increased liability they would assume. This would be prohibitively time-consuming and expensive. Alternatively, and ironically for conservative critics of Section 230, platforms could take a completely hands-off approach to curating content, but the results would likely be too violent, pornographic, or offensive to attract many eyeballs.

There are also attempts to set standards for privacy and online advertising and to address online “addiction” and hold companies accountable for it. Some seek to bring the gig economy into the regulatory maze of labor law. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve and the Securities Exchange Commission may seek to assert their authority over the payments processing sector just as cryptocurrencies are beginning to emerge.

Fortunately, it is still hard to pass laws. But overseas courts and legislators are hard at work at dismantling the open social media ecosystem.13 The pressure to regulate has intensified thanks to the emergence of two other powerful regulatory centers that are vying with America to set the gold standard for global technological regulation. While the

U.S. has traditionally aimed at empowering technology users, it faces competition from two different models. The European Union aims to protect technology users in paternalistic fashion. China wants to control how people use technology. A survey of the various regulatory initiatives undertaken by these administrative rivals is beyond the scope of this paper, but for a global industry, regulations imposed by jurisdictions that encompass a large percentage of global population and GDP will affect American companies and consumers.14

We argue instead for innovation and the separation of technology and state. The longest journey does not merely begin with a single step; it requires not stepping backward. In the present instance, that means not enacting misguided laws and regulations.

Policy makers, including Republicans, must pay special attention to how these various proposals would expand invasive administrative bodies like the Federal

Trade Commission (FTC), the Federal Communications Commission, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and other agencies.

BOX 1. Major Pieces of Internet Legislation Passed Since the Heyday of AOL and Netscape.

Deregulatory

- The Telecommunications Act, the first significant update to telecommunications law since the 1934 Communications Act,16 created the “information services” classification, separate from telephone and cable services and not subject to regulations governing either.17

- Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act largely protects websites from liability over content created by third-party users, creating a safe harbor for websites that choose to moderate content. Prior to Section 230, any attempts to moderate content meant platforms could be held liable for all user-generated content.

- Title II of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act provides a safe harbor for Internet service providers, including websites, against liability for digital copyright infringements by third-party users. Providers must meet certain conditions to qualify for protection.18

Regulatory

- The Children’s Online Privacy Act prohibits websites and online services that are either directed at children or collect personal information of children under a certain age before meeting several conditions.19

- The Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography and Marketing (CAN-SPAM) Act governs commercial emails. Among other provisions, CAN-SPAM prohibits deceptive email subject lines, requires identifying information for the sender, and mandates an opt-out feature for recipients. It preempts state laws relating to commercial email, aside from those covering fraudulent or deceptive content.20

- The Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act scales back Section 230 immunity in several areas related to online content regarding prostitution and sex trafficking.21

Old-school telecommunications, transportation, and infrastructure have long been highly regulated, with government-supported monopoly in some instances. The Internet still offers an opportunity to show that spontaneous order can work to serve consumers and society better than lawmakers. Which will prevail, innovation or the central directives of the regulatory state?15

The Bleak Litany of Restrictive Proposals

In this report, we identify specific legislative or regulatory proposals that raise alarm bells. We also identify broad categories of control of which these proposals are examples. The report also stresses how a large administrative state grows at the expense of First Amendment rights, property rights, and free enterprise.

An “Internet Bill of Rights”: Proposals that Conflate Public and Private Spheres and Ignore the Dichotomy between Positive and Negative Rights

The concept of “Internet Exceptional- ism” is a common theme across these proposals. It postulates that the Internet is a unique kind of technology that requires new conceptions of law and economics.22 For example, Professor Tim Wu of Columbia University, famous for popularizing the concept of “net neutrality,” recently said that tech companies “had reinvented economics, reinvented business as we knew it.”23 This prism of novelty allows for a circumventing of norms surrounding the concept of rights in the United States. Instead of rights guaranteed to all private actors by restrictions on government through a negative rights framework, tech utopians advocate for positive rights guaranteed by government, provided at the expense of private companies and their consumers.

Under this vision, Internet users have entitlements, while those who help make the easy-to-use commercial Internet possible in the first place have obligations that supersede their own rights. As part of the lay of the land of the tech policy debate, we see longstanding calls for a “Magna Carta” or “new contract” for the Web from pioneer Sir Tim Berners-Lee.24 Worried about “fake news” and data protection,25 he has called for breaking up the tech giants.26 Such sentiments are shared by U.S. legislators like Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA), who have devised versions of a highly regulatory Internet Bill of Rights, using terminology conflating public and private spheres.27 Conservatives have proposed their own versions of this folly, largely in the area of content regulation.

Yet, if lawmakers were to undermine the negative-rights framework in regards to the Internet, we will lose the kind of rapid progress that has made the Internet seem “exceptional.” Imposing positive rights obligations upon Internet service providers and platforms would result in a significant drop-off in investment and innovation in the sector. It is not hard to understand why.

Positive rights require that resources are allocated in specific ways. If resources must be allocated in certain ways, then companies and their investors no longer enjoy complete property rights, which are integral to investment. Positive rights also create a drain on available resources. Like burning a candle at both ends, positive rights obligations on firms limit the resources available for risk-taking, the key to innovation.

The impetus behind an Internet bill of rights is at least nominally pro-consumer. Yet, as economist Milton Friedman said, “One of the great mistakes is to judge policies and programs by their intentions rather than their results.”28 While some users may find value in the various prescriptive guarantees, if the majority of consumers truly valued the protections or guarantees of an Internet bill of rights, the market would already be providing these features.

Yet, as the data show, users actually place little value in such features.

Rep. Khanna’s Internet Bill of Rights primarily seeks to protect data privacy, with six out of 10 provisions related to data collection. When asked, Americans certainly want companies to do a better job in protecting data privacy.

However, economics teaches us that human wants are limitless and what truly matters is how people value something relative to the alternatives. According a recent survey of over 3,000 American Internet users, only 26 percent said they would be willing to pay a monthly subscription fee for greater privacy protection.29 Many services already provide this privacy for a small fee, and in some cases for free.30 Apple recently made the privacy features of its iPhone line a major facet of its advertising campaigns.

Privacy-centric search engine DuckDuckGo has grown from approx- imately 16 million queries in 2010 to more than 15 billion in 2019.31

Consumers should be free to select the products and services that best meet their privacy needs and provide the best results. Imposing positive rights obligations on the Internet sector would reduce investment and innovation.

Consumers would ultimately have fewer choices in exchange for “rights” that the vast majority of consumers may not value all that much. The $50 smartphone makes the technology available to all, at the cost of privacy. When regulation produces fewer options in the market and a lack of investment in new competition, consumers are worse off at the margin, as they lack realistic alternatives to punish companies by taking their business elsewhere.

This is why the U.S. Bill of Rights places restrictions on government and not on private actors. The market is highly responsive to what consumers value, with consumers voting countless times every second with their attention, feet, and wallets; firms grow when they provide what people value. Government, on the other hand, faces no competition, is only rarely held to account, and tends to grow unimpeded.

Censorship of Social Media Content and Bias

The safe harbor provided by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act is a major reason why America leads the world in online technology investment and innovation.32 Section 230 protects tech platforms from liability over content posted by third- party users. For example, if a person posts a libelous Facebook status about you, only the person who posted it, not Facebook, is legally responsible for the content.

While critics of Section 230 exist on both sides of the aisle for various reasons, the law is largely responsible for the Internet as we know it today. Without it, platforms—from online marketplaces, to social media to review sites—would either be unmoderated cesspools or simply would not exist as largely free and open to users. Prior to Section 230, any attempts to moderate content meant platforms could be held liable for all user-generated content. Section 230 addresses the impracticality and excessive risk of assuming liability for all the countless pieces of content uploaded by users by granting tech companies the ability to moderate content as they see fit.

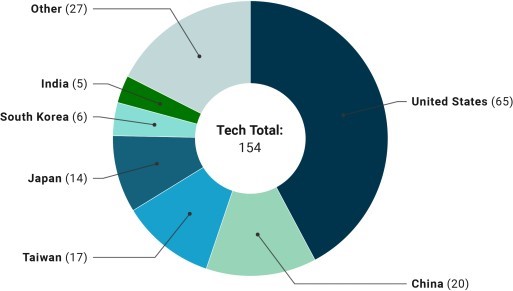

Where The World’s Largest Tech Companies Are

Image via Jonathan Ponciano, “The Largest Technology Companies In 2019: Apple Reigns as Smartphones Slip and Cloud Services Thrive, Forbes, May 15, 2019, ttps://www.forbes.com/sites/jonathanponciano/2019/05/15/worlds-largest-tech-companies-2019/#21e4b2bc734f.

The 10 Largest Tech Companies in the World

Image via Jonathan Ponciano, “The Largest Technology Companies In 2019: Apple Reigns as Smartphones Slip and Cloud Services Thrive, Forbes, May 15, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/jonathanponciano/2019/05/15/worlds-largest-tech-companies-2019/#21e4b2bc734f.

Meanwhile, conservatives accuse tech giants of using content moderation under Section 230 to promote online bias and censor right-leaning voices, and in response they seek compulsory redress. Yet, the Internet is actually one of the few realms, like talk radio, not dominated by left-leaning views, and the drive to change that is at the root of some liberals’ calls to regulate it.33 Still, right and left agree on one thing: The federal government should lord over speech, with the First Amendment’s free speech guarantees thrown by the wayside. Instead of a free online marketplace of ideas, we would get one regulated by agencies like the Federal Trade Commission.

One side would partner with government to ban “harmful speech,” while the other would compel and then certify political neutrality. Some companies cater to this mindset, glossing over the distinction between government and private parties.34 Collectively, all ignore the fact that, as noted, First Amendment speech and association rights are negative rights that constrain the government, not private parties, from restricting or compelling your speech.

- The Ending Support for Internet Censorship Act, sponsored by Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO) would require “tech companies to moderate content without political bias as a condition of civil immunity.”35 This policy would deny property rights, compel speechand add considerably to an already large administrative state bureaucracy. In order to retain immunity from liability for user-generated content under Section 230, a “covered company” would have to obtain an “immunity certification” every two years from the FTC by assuring a majority of the (unelected) commissioners that it does not moderate content provided by others in a politically biased way.36

It also mandates arbitrary thresholds regarding which parties it would regulate. A “covered company” needing objectivity certification would be one with more than 30 million active U.S. monthly users, 300 million worldwide users, or $500 million or more in annual global revenue. Along with the false premise of private censorship in the bill’s title, one cannot prove the negative of non-bias, so the bill is inoperable and susceptible to partisan disputes over the meaning of objectivity. That is a battle that conservative proponents will ultimately lose, since what will be regarded as politically objective by a future FTC will not necessarily match Hawley’s— and many other conservatives’— vision.37

- The Limiting Section 230 Immunity to Good Samaritans Act was also introduced by Sen. Hawley.38 To understand this legislation, it is necessary to get an understanding of Section 230 of the 1996 Communi- cations Decency Act. Part of what makes Section 230 special is not what it does but rather what it does not do. The relatively short law provides “Protection for ‘Good Samaritan’ Blocking and Screening of Offensive Material.”39 The law’s title states as its purpose: “To amend the Communications Act of 1934 to provide accountability for bad actors who abuse the Good Samaritan protections provided under that Act, and for other purposes.” The text does not define the term “Good Samaritan,” which suggests that the law’s authors acknowledge a simple truth: The definition of a Good Samaritan is subjective, as are the definitions of what would constitute “bad actors” or “abuse” in regard to Section 230.

In other words, the Limiting Section 230 immunity to Good Samaritans Act seeks to accomplish the impossible and define what constitutes being a Good Samaritan, or at least a Web service acting in “good faith.” For Web services that are seen to be acting in bad faith by selectively enforcing their terms of service on content moderation, the bill allows for civil liability of up to $5,000. Like the Ending Support for Internet Censorship Act, the bill also sets arbitrary thresholds over which entities it covers. Specifically, it outlines that it only applies to services with over 30 million U.S. users, 300 million global users, or $1.5 billion in global revenue. 40

There are several problems with this approach. First, just as the definition of a Good Samaritan is subjective, many decisions on content moderation come down to subjective judgements. The spirit of the bill thus essentially disincentivizes moderation at the margins for fear of exposure to liability. This would mean more offensive and objectionable content online where there was none before.

Second, the bill has a huge loophole that renders it essentially futile. It would allow for Web services to include a right to selectively enforce said terms in their terms of service. As Gizmodo’s Dell Cameron notes, “the changes to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act proposed by Hawley do not appear to place any new restrictions on how companies define their own moderation policies—only that they stick to, and evenly apply, whatever rules they ultimately decide upon.”41

Third, by stipulating that the bill only applies to the largest Web services, it provides an incentive for these services to become even larger and more dominant over online discourse.

Upstart competitors approaching any of the bill’s three metrics would be incentivized to sell to larger competitors that already exceed those thresholds—and have the compliance personnel to deal with that.

- The Stop the Censorship Act, introduced by Rep. Paul Gosar (R-AZ), would limit moderation of “objectionable” content by only granting immunity when companies act in “good faith” to remove “unlawful content.”42 Under such a regime, companies would be forced to host endless amounts of content against their will—regardless of whether or not they would be deemed in compliance with the impossible non-bias standard in Hawley’s bill. This would amount to a violation of the speech and association rights of the covered firms.

Rep. Gosar has frequently made the claim, common among critics of Section 230, that tech companies are unlawfully acting as both a “publisher” and a “platform.” In a tweet from September 18, 2019, he wrote: “Facebook makes a judicial admission it is a publisher not a platform. As a publisher it can assert editorial control. But it can also be sued for defamation and tortious interference. Sec. 230 of the CDA protects platforms. Not publishers.”43 No part of the actual law makes this distinction.

Professor Jeff Kosseff, a cybersecurity law professor at the U.S. Naval Academy and perhaps the nation’s leading expert on Section 230, said on the platform-publisher distinction:

I’m not quite sure what their parameters are for publisher or platform. Are they saying you don’t do any moderation at all? A free for all? I seriously would not want to be on the internet at all if that was the case. … I don’t know where these people are drawing the line between platforms and publishers. All I can say is that Congress, at least at the time, did not intend that distinction.44

Yet an Internet Kosseff seriously would not want to be on would be the default setting for tech platforms and other websites under the Stop the Censorship Act, as consumers would be forced to choose to opt in to see or receive moderated content. Should a social media page filled with hateful, violent, and sexually explicit content really be the default setting?

- The Biased Algorithm Deterrence Act would effectively abolish Section 230 immunities by commanding that:

[A]n owner or operator of a social media service that displays user-generated content in an order other than chronological order, delays the display of such content relative to other content, or otherwise hinders the display of such content relative to other content … shall be treated as a publisher or speaker of such content.45

This bill literally puts others’ words in the platforms’ mouths, by declaring the platform to be the speaker. It also mandates a chronological presentation of content. Algorithms that learn what you are interested in are actually useful to readers. Anyone who has tried installing a social media plug-in that forces the display of content in chronological order will know what happens when a friend has uploaded an album of holiday photos—endless scrolling to get to the next interesting item.

These proposals’ violations of private companies’ speech and association rights alone, not to mention the impossibility of policing objectivity when government agents have plenty of their own biases, render these proposals problematic, to put it lightly. Forcing companies to host content against their will goes beyond simple control over their platforms. There are significant implications for the tangible property of these firms under each of these supposed anti-censorship proposals. While cyberspace may seem unlimited, it is not. Tremendous resources are dedicated to hosting all the data uploaded to the Internet. In 2019, an estimated $210 billion was spent worldwide on data centers.46 Forcing companies to host any and all lawful content would dramatically increase the physical infrastructure needs of tech platforms, a de facto tax of potentially hundreds of billions of dollars.

Ironically, the tremendous resource costs related to hosting content, under these anti-censorship proposals, could lead to forced limiting of online speech due entirely to resource constraints. In this way, all sorts of spam, violent, sexual, and other objectionable content that is otherwise discarded could impose a sort of heckler’s veto over the political content Hawley, Gosar, and their allies are trying to protect.

Congress should not stand in judgment of others’ acceptable or unacceptable bias or speech. Regardless of all the various legal and practical problems with implementing such policies, progressives have already teed up an abundance of subjective, ill-defined, and open-ended categories of speech to be regulated, including misinformation, disinformation, harmful content, and hate speech.

One likely effect of content restraint would be a clampdown on anonymous speech and criticism of unorthodox views. In fact, in a self-regulatory move, Facebook has decided to allow more political content on the platform in exchange for stricter rules to ensure the true identity of the speaker can be identified.47 Moreover, if content rules are good for social media, why they are not also good for government websites, mainstream media, and publicly funded university curricula?

These proposals violate the spirit of the First Amendment by restricting private citizens’ speech and leaving the government not only unshackled, but more powerful.

Trial Ballooning a Sweeping Federal Takeover of the Internet

In July 2018, the Columbia Journalism Review (CJR) reported on a leaked draft white paper from Sen. Mark Warner (D-VA) that contained a wide-ranging slate of proposals to treat tech companies as essential facilities and to regulate content and speech.48

The white paper, titled “Potential Policy Proposals for Regulation of Social Media and Technology Firms,” cited anonymity using trolls, misinformation, and election interference as justification. Warner expressed alarm that “bots, trolls, click-farms, fake pages and groups, ads, and algorithm-gaming can be used to propagate political disinformation.”49 Proposed solutions, which Warner refers to as “guard rails,” include:

- Labeling of automated “bot” accounts;

- Requiring location verification;

- Limiting certain elements of anonymity;

- Limiting Section 230 immunity for re-uploaded content;

- Imposing liability for defamation, false light, and deep fakes;

- Audits of tech company algorithms, and

- Defining certain services to be essential facilities.50

Reason correspondent Elizabeth Nolan Brown called it “plans for a government takeover of the Internet.”51

The loss of the civil right of anonymous online speech is an unexplored vulnerability in the various social media regulatory campaigns, with Warner leading the charge.52 The CJR’s Matthew Ingram notes:

When it comes to misinformation, the Warner paper says one possible proposal is that platforms be required to label automated bot accounts, and also do more to identify who is behind anonymous or pseudonymous accounts. If there’s a failure to do these things, it says, the Federal Trade Commission could step in with sanctions.53

If companies like Facebook grew thanks to the protections of Section 230, newly formed social media companies have the right to do the same, and politicians the duty not to interfere. Future networks that do not yet exist deserve the same clear path.

The Internet has given individuals power over their speech, providing a platform for both popular and unpopular ideas. It is a good thing that the Internet allows the questioning of orthodoxies and the bypassing of gatekeepers. Yet, attempts are now under way to reestablish gatekeepers. For all the talk of regulating algorithms, such efforts seek to certify government “algorithms” while demonizing those of the private sphere.

Helicopter Government: Saving Children from Parents’ Failure in the Duty to Supervise Online Activities

- Sen. Josh Hawley teamed with two Democrats, Sens. Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut and Ed Markey of Massachusetts, to sponsor the Protecting Children from Abusive Games Act (S. 1629).54 Targeting what he calls the “addiction economy,” Hawley alleges, “When a game is designed for kids, game developers shouldn’t be allowed to monetize addiction.55 And when kids play games designed for adults, they should be walled off from compulsive microtransactions. Game developers who knowingly exploit children should face legal consequences.”56 Games would be banned from having loot boxes, defined as “microtransactions offering randomized or partially randomized rewards to players.” (If you ever bought a Cracker Jack box hoping for a good prize, you might be familiar with the concept.) The bill also targets “pay-to-win” mechanics that “manipulate a game’s progression system … to induce players to spend money.”57

The Entertainment Software Association argues that loot boxes do not constitute gambling, and describes tools the sector provides “that keeps the control of in-game spending in parents’ hands. Parents already have the ability to limit or prohibit in-game purchases with easy to use parental controls.” In Hawley’s perspective, parents are not competent to supervise the purchase of digital weapons for junior’s Fortnite game and need the help of the nanny state.

- The Protecting Children from Online Predators Act (S. 1916), also sponsored by Hawley, would prevent companies like YouTube from recommending videos featuring minors.59 As Reason’s Elizabeth Nolan Brown describes it:

Teen video makers couldn’t rely on algorithms to recommend any of their content. Sites like Facebook would be prohibited from recommending family videos featuring children to grandma and grandpa.60

Relatedly, a Federal Trade Commis- sion rulemaking on the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) is underway.61 The bill was passed 20 years ago to prevent online data collection from children under 13 years of age. The FTC oversees enforcement and issues fines to websites that are not in compliance with the regulations. As CEI noted in comments submitted to the FTC, COPPA “exceeds its mandate and ultimately harms children by creating disincentives towards the production and distribution of content directed towards children while not providing any additional privacy protections.”62 As noted, outcomes are far more valuable than intent in measuring public policy. Meanwhile, Google has reached a settlement with the FTC and promises to improve the protection of children’s data on YouTube.63 Yet, there is still no substitute for parents’ supervision, not just in tech concerns, but everywhere.

Helicopter Government, Continued: Saving Dumb Adults from Online Addiction, Manipulation, and Nuisance

- The Social Media Addiction Reduction Technology (SMART) Act (S. 2314), also sponsored by Hawley, is filled with extremely specific paternalistic rules aimed at stemming online addiction, including banning autoplay videos and infinite scrolling, and limiting social media use to 30 minutes a day.64 The latter clock would be reset every month even if one chooses to change it. But why stop there when there are TVs and newspaper subscriptions to ban?65 The SMART Act would also require a make-work report:66

Not less frequently than once every 3 years, the [Federal Trade] Commission shall submit to Congress a report on the issue of internet addiction and the processes through which social media companies and other internet companies, by exploiting human psychology and brain physiology, interfere with free choices of individuals on the internet (including with respect to the amount of time individuals spend online).

Every generation has faced new threats to the moral order. It was comic books’ effect on youth in the 1960s, Guns ‘n Roses in the 1980s, and now it is online addiction. It seems technology is no barrier for puritans seeking to ruin someone else’s fun. The SMART Act managed to attract no cosponsors.

- The Deceptive Experiences to Online Users Reduction (DETOUR) Act (S. 1084), sponsored by Sen. Mark Warner (D-VA) and Sen. Deb Fischer (R-NE), seeks “to prohibit the usage of exploitative and deceptive practices by large online operators and to promote consumer welfare in the use of behavioral research by such providers.” Specifically, it would grant new powers to the Federal Trade Commission to police “unfair” and “deceptive” acts by sites with more than 100 million active monthly users:

… to design, modify, or manipulate a user interface with the purpose or substantial effect of obscuring, subverting, or impairing user autonomy, decision-making, or choice to obtain consent or user data; [or] to subdivide or segment consumers of online services into groups for the purposes of behavioral or psychological experiments or studies, except with the informed consent of each user.

This refers to prompting users to take actions they presumably otherwise would not. Examples include yes or no buttons of different sizes, suggestions that others are about to buy an item in hopes of closing a sale, making alternative settings difficult to access, and luring kids to ask their parents for in-app purchases.67 The problem, allegedly, is the possibility of websites goading people into giving up more information than intended, through “prompts to access phone and email contacts in order to keep using the platform.”68 Warner points to fake smudges tricking users to click on an ad.69 Sen. Hawley is on board, too, since dark patterns “feed tech addiction.”70 Apparently, the Internet is a giant haunted house manipulating everyone to give up personal data and information via “dark patterns.”

The DETOUR Act retains government’s protected-class status. Not only does it expand the power of the FTC, it hypocritically fails to restrain politicians’ purchase of online political ads and grassroots rallying for election.71

Lawmakers Threaten the Right to Anonymous Speech

The tech regulatory proposals described above threaten the right of anonymous speech, which is elemental to our right to speak and petition for redress of grievances, since sometimes speaking can make one a target for retaliation. Indeed, anonymous political speech was integral to America’s founding, with the publishing of the Federalist Papers initially under the pseudonym “Publius.” This stands in contrast to current policy makers’ professed concerns over our data privacy in commercial contexts.

The Honest Ads Act proposal (S. 1356) from Sens. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and Mark Warner (D-VA) aims “to enhance the integrity of American democracy and national security by improving disclosure requirements for online political advertisements.”72 The bill would expand the power of the Federal Election Commission and require tech companies to disclose how they target online political ads and the cost of those ads. Both Facebook and Twitter have endorsed it.73

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg proclaimed that election “interference is a problem that’s bigger than any one platform, and that’s why we support the Honest Ads Act. This will help raise the bar for all political advertising online.”74 Echoing that, Facebook Ads Vice President Rob Goldman wrote:

[W]hen it comes to advertising on Facebook, people should be able to tell who the advertiser is and see the ads they’re running, especially for political ads. … That level of transparency is good for democracy and it’s good for the electoral process.75

Russia did not buy that many ads, in the grand scheme of things. Yet, the bill includes an exemption for “a communication appearing in a news story, commentary, or editorial distributed through the facilities of any broadcasting station or any online or digital newspaper, magazine, blog, publication, or periodical,” unless a political body controls it—all this because Russia bought $100,000 worth of ads.76 If people are that malleable, they may not be suited for voting in the first place.

The bill is not limited to candidates, but encompasses issue advocacy as well. Section 8 (4) (III) requires individuals purchasing political advertisements on social media to disclose their name, address, and phone number (and those of associates) and requires online platforms to keep a record of anyone spending $500 on political ads. In that sense, the bill contradicts its original intent. It was intended to keep tabs on potential Russian-style interference in elections, but Section 8(1)(A) could expose private information to public inspection in a machine-readable format, which in turn could make individuals vulnerable to online harassment.77

- Related in spirit is Sen. Diane Feinstein’s (D-CA) Bot Disclosure and Accountability Act (S.2125).78 It prohibits candidates, campaigns, and political organizations from using “social media bots in political advertising, which is intended to deceive voters and suppress human speech.” The legislation would empower the Federal Trade Commission to enforce social media transparency requirements regulating “the use of automated software programs intended to impersonate or replicate human activity on social media.”79

“Fake news” does not undermine democracy until governments assume the authority to label information as such and to squelch speech. Anonymous speech is a cornerstone of our republic: After all, Thomas Paine signed Common Sense “An Englishman” and the Federalist Papers authors used pseudonyms as did John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon when they penned Cato’s Letters.80

Compulsory Disclosure of Internal Business Processes and Monetization of Data

- The Designing Accounting Safeguards to Help Broaden Oversight and Regulations on Data (DASHBOARD) Act (S.1951) would require social media platforms to disclose how much their user data is worth, presumably to determine for how much big tech is selling, or would sell, their data. Specifically, it would require any “commercial data operator” with more than 100 million unique monthly users to, at least every 90 days, “provide each user of the commercial data operator with an assessment of the economic value that the commercial data operator places on the data of that user” and describe the types of data collected and any tangential uses of it. The bill would also impose limits on data retention and the ability to delete it.81 The Federal Trade Commission would enforce all these requirements. The Securities and Exchange Commission would oversee annual or quarterly filings (parallel to financial filings) related to the value of aggregate data, and develop accounting schemes to attempt an impossible calculation of the “value” of the data that tech firms gather or collect from users.

Internet Privacy

Top-down privacy proposals would generally force online operations to reveal their collection policies, secure that information, and allow users to control its use. Advocates want the federal government to supersede states in order to avoid a patchwork of rules. Aside from the federalism counterarguments, former Federal Trade Commission Chairman Tim Muris long ago noted that privacy abuses are lessened by the fact that national companies like Visa require sites with which it does business to adopt privacy policies.82

Large players have often supported legislation, while small businesses are hurt more by onerous regulation than large operations with plenty of legal assistance. Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg invited a data privacy law and further regulation in 2018 Senate testimony:

I actually am not sure we shouldn’t be regulated. I think in general technology is an increasingly important trend in the world and I actually think the question is more, what is the right regulation rather than “Yes or no, should it be regulated?”83

Zuckerberg, whose company argues that sharing on social media forfeits any expectation of privacy,84 later stated:

I also believe a common global framework—rather than regulation that varies significantly by country and state—will ensure that the internet does not get fractured, entrepreneurs can build products that serve everyone, and everyone gets the same protections.85

- The Do Not Track Act (S. 1578), also introduced by Hawley, calls for the government to establish a national “Do Not Track” system “to provide consumers a legally enforceable right to browse the internet privately, without data tracking.”86 This system will allow users to attach a “signal” to their devices that all websites and online applications must be able to recognize and therefore not target ads at them. Without providing any detail on how this system will work on a technical level, the bill demands that it be up and running in just six months. In addition, the legislation would require websites and applications to inform users about the Do Not Track system if they are not already enrolled, requiring a notification from each website and application the first time a signal is not detected and each subsequent 30th time.

The Do Not Track Act illustrates the fundamental problem with privacy legislation. Acceptable privacy means something different to everyone.

Government’s role is not to dictate the terms of privacy contracts, but to enforce companies’ promises.

Governments need not mandate privacy, but allow it.87 A world where people have control of their information cannot be reconciled with government being in control of what information can be created and communicated.

- The American Data Dissemination (ADD) Act, sponsored by Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL), would apply the Privacy Act of 1974, which covers government agencies, to private Internet service providers.88 Like most privacy legislation, it would impose onerous requirements on virtually all businesses, yet do nothing to actually protect privacy. As Will Rinehart, then with the American Action Forum (now with the Center for Growth and Opportunity at Utah State University), described it:

In total, every business in the United States would be subject to an onerous privacy regime. And because the ADD Act is based on the Privacy Act of 1974, it too will commit the same errors by focusing on data collection and disclosure. But collecting and disclosing data isn’t especially problematic. What is worrying is how a company might use information in a way that could be harmful to consumers.89

- The Social Media Privacy Protection and Consumer Rights Act of 2019 (S. 189), sponsored by Sen. Amy Klobuchar, would mandate that behavioral data collected on social media after registration be flagged to users as being used and shared.90 The marvelous thing about the Internet is that one can contact and learn about anyone and anything. The downside is that the reverse is often true. Of course, websites have long collected and marketed information about visitors. Behavioral marketing firms “watch” user clickstreams to develop profiles or inform categories to better target future advertisements. While inarguably beneficial, the process stokes understandable privacy concerns. Privacy policies need to be filtered through the lens of the entire society’s needs. We must consider the impact on 1) consumers; 2) e-commerce and commerce generally; 3) broader security, cybersecurity, homeland security and critical infrastructure issues; and finally 3) citizens’ Fourth Amendment protections.91

- The Own Your Own Data Act, sponsored by Sen. John Kennedy (R-LA), would force social media companies to disclose to individuals how they were using their data and create a property right in data “that an individual generates.”92 The inherent properties of data make creating an individual property right legislatively in the area difficult, costly, and detrimental to innovation.93 Privacy is a relationship, not a thing.94 There is an infinite range between anonymity and full authentication. It is incoherent to say there is an automatic property right in privacy, that no one can say anything or use any information about somebody else, any more than we can be forbidden to gossip. But it is conceivable that in various contexts— such as the medical, insurance, and financial fields—contracts are created regarding certain information and its disclosure that can be considered a property right of sorts (as intellectual property may be), but not a blanket property right in “personal info.”

- The Information Transparency and Personal Data Control Act, from Rep. Suzan DelBene (D-WA) and with 24 cosponsors, directs “the Federal Trade Commission to promulgate regulations on sensitive information.”95 What counts as sensitive? The government will decide, with said standards not applied to itself, of course. The legislation would give users the option to opt in to the collection, stor- age, and sharing of their data. It also would require companies to inform consumers if and with whom their sensitive information will be shared. However, the bill stops short of em- powering consumers to sue companies or letting states experiment with their own approaches to data privacy.”96

- The Balancing the Rights of Web Surfers Equally and Responsibly (BROWSER) Act, sponsored by Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN), a vocal advocate for federal privacy legislation, would require both Internet service providers (ISP) and edge providers to obtain opt-in consent from consumers in order to use their data.97 The bill also preempts state privacy laws and would at least avoid the interstate commerce clause violation of a patchwork of 50 state privacy regimes—which would be a costly and complicated compliance nightmare for ISPs and edge providers.

Privacy Mandates on the Frontier: Home Devices and Public Surveillance via Facial Recognition and Biometrics

Privacy concerns have moved from marketing and online tracking into larger realms like real-time surveillance in cities.98 Since these realms involve public property and infrastructure, the dangers are real and bring the issue of government information collection to the forefront.99 This offers a chance to make the proper value assertions, but seemingly Washington will have no part of that. One in four Americans now owns a voice-activated smart speaker of one kind or another.100 And there is always the ultimate opt-out of not buying or using these features.

- The Commercial Facial Recognition Privacy Act, sponsored by Sens. Roy Blunt (R-MO) and Brian Schatz (D-HI), purports to “strengthen consumer protections by prohibiting commercial users of facial recognition technology (FR) from collecting and re-sharing data for identifying or tracking consumers without their consent.”101 While government may use technology to identify a match to a wanted individual in a database for whom they had already undertaken Fourth Amendment safeguards to identify, incidental recognition data on other individuals “passing by” must not be retained by authorities. On the private sector side, people may be willing to give up “privacy” in exchange for services they want.

Competition and avoidance of data breaches, backed by companies’ reputations for security and safeguarding, are more powerful than regulation by the quarter most eager to invade privacy and track everyone: the government itself.

Antitrust Regulatory Manipulation and Corporate Breakup

Antitrust regulation is likely to be one of the highest-stakes regulatory battles in the technology sector.102 President Trump and members of Congress from both parties have threatened antitrust actions against Google, Amazon, and Facebook over political grievances often unrelated to competition. In March 2019, the European Commission fined Google €1.49 billion ($1.7 billion) for violating EU antitrust laws in the firm’s search business.103 State attorneys general in the United States and federal regulators have threatened to bring their own cases.

In the Google cases, progressives tend to object to Google’s market share in online advertising, search, and that of its Android operating system. Conservatives often attack the company claiming its search results have an anti-conservative bias.

In a potential Amazon case, progressives are concerned with Amazon’s market share in retail and its labor relations. President Trump seems to have a personal grudge against Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, who separately owns The Washington Post, which often runs coverage critical of Trump. The paper is unaffiliated with Amazon.

Regarding Facebook, progressives focus on the company’s dominance in social networking, its tendency to buy out competitors, and privacy issues.

Conservatives believe Facebook’s algorithms and software designers are biased against conservatives and censor conservative viewpoints.

None of these cases have merit. Most of the reasons are addressed in a 2019 CEI paper, “The Case Against Antitrust Law.”104 That paper focuses more on general theory than on specific cases. This section will apply those arguments to today’s Google, Amazon, and Facebook antitrust debates.

The Relevant Market Fallacy. The relevant market fallacy is one of the most common misconceptions behind antitrust policy. A company’s critics almost invariably assume that its relevant competitive market is smaller than it actually is. Google’s share of Internet search is actually much smaller than many antitrust advocates believe. Common searches ranging from Netflix recommendations to match- finding algorithms on online dating sites rely on search engines other than Google. In fact, their proprietary search algorithms are often a competitive selling point. The only area of Internet search where Google truly has a monopoly is on Google searches.

Amazon controls roughly half of online retail, for example, but only about 5 percent of total retail. Which is the proper relevant market? Facebook dominates social networking. But as a way to use leisure time, it competes with television, movies, YouTube, books, music, friends, families, and more.

Solving problems and continuing to innovate may require “collusion” among service providers of the very sort that is going to enrage the “open Internet” and antitrust advocates. “The Case Against Antitrust Law,” goes into greater detail about the productive case for some forms of collusion.105 CEI has also detailed how these large firms are actually fiercely competing with each other across a number of fronts.106

Net Neutrality Mandates and the Denial of Property Rights in Complex Assets

It has been two years since the repeal of heavy-handed title II regulation of the Internet, known as net neutrality regulations, and none of the dire predictions of net neutrality supporters have come to pass. The Internet is not just intact, but is thriving.

- The Open Internet Act of 2019 (H.R. 1006), sponsored by Rep. Robert Latta (R-OH) would “amend title I of the Communications Act of 1934 to provide for internet openness.”107

- This bill is similar to The Promoting Internet Freedom and Innovation Act of 2019,108 sponsored by Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-WA) and untitled legislation introduced by Rep. Greg Walden (R-OR).109 With some nuances, this category of bills involves reinstituting bans on blocking content online; slowing data, a practice known as throttling; and preventing so-called “fast lanes” that prioritize certain traffic across the network, presumably for an increased fee. Those practices were legalized in the Federal Trade Commission’s repeal of net neutrality regulations, along with ending the Internet’s classification as a Title I information service.110

Distortion via Government Ownership, Subsidies, and Industrial Policy in Tech R&D and Production

Some legislation in the 116th Congress was aimed at promoting broadband and 5G, but this is best carried out by regulatory liberalization and easing permitting restrictions. And unfortunately, while the FCC has been eliminating cumbersome net neutrality regulations and working to bring more spectrum to market, it also has been pushing unwise federal funding of broadband deployment in certain sectors.111

- The Accelerating Broadband Development by Empowering Local Communities Act of 2019, introduced by Rep. Anna Eshoo (D-CA), would nullify rules issued by the Federal Communications Commission that revoke state and local authority to regulate telecommunications equipment deployment.112 It would seem to be the dead opposite of needed federal preemption, which would eliminate the patchwork maze of costly and complicated state and local regulatory regimes.

- The Office of Rural Broadband Act, sponsored by Sen. Kevin Cramer (R-ND), would create an office at the FCC to coordinate rural broadband deployment efforts.113 This is as the FCC itself fights to shrink the regulatory underbrush, not expand it.

Government Subsidies and Intervention in the Gig Economy, Tech Workforces, and Education

- The Championing Apprenticeships for New Careers and Employees in Technology (CHANCE in Tech) Act would provide industry intermediaries, like state tech associations, the ability to receive federal grants to develop apprenticeships within the technology sector.114 These are baby versions of grander schemes for “free college.”

- The Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act of 2019, sponsored by Rep. Bobby Scott (R-VA), would likely cripple gig economy firms by destroying their business model. Specifically, it creates a federal version of the “ABC” test in AB5, the recently enacted California law that seeks to reclassify large numbers of independent contractors as employees eligible for unionization.

The many thousands who work for sharing economy platforms because they value flexibility or extra income would lose their gigs. The millions of dollars of consumer surplus added to the economy by these firms would vanish. The PRO Act passed the House in 2019 but has so far languished in the Senate. It is likely that future administrations might attempt to reclassify workers by administrative fiat, as the Obama administration attempted.

California’s AB5 was an attempt to force gig economy firms like Uber, Lyft, and Taskrabbit to classify independent contractors as employees, giving them full benefits and the right to unionize. AB5 uses what is called an ABC test to determine if a worker is an independent contractor or a formal employee. It consists of three questions:

- How closely is each worker supervised or directed? Do they check in with a boss every day? Or do they work mostly on their own and have wide discretion on how to do their job?

- Is their work part of the company’s core business? (For an Uber driver, the answer is yes. For an accountant or a maintenance worker, maybe not.)

- Is the hiring company the contractor’s sole or dominant customer? Is the job mostly in the contractor’s area of specialty or expertise?115

The bill text is vaguely worded.116

In practice, nearly any freelancer qualifies as a formal employee under AB5, but a lot of job arrangements are somewhere in between. While those firms have so far successfully resisted the effort, many thousands of independent contractors in California have lost their jobs, been dropped from in-state work, or been forced to move out of state.117

- The Gig Is Up Act, sponsored by Rep. Debra Haaland (D-NM), also targets gig economy firms. It would require businesses to pay employer and employee portions of Social Security and Medicare taxes when they contract with at least 10,000 independent contractors and gross at least $100 million in a calendar year. While not as existential a threat to gig economy firms as AB5 or the PRO Act, it would still impose significant costs on national firms, reducing the attractiveness of their business model and probably reducing the amount they are able to pay workers.

Moves Toward the Regulation of Virtual Currencies

For more than three years, the Securities and Exchange Commission has been lording over the cryptocurrency and blockchain technology sectors, including in areas over which it has no jurisdiction granted from Congress. It has been doing so via arbitrary enforcement actions and “regulatory dark matter”—agency issuances, including guidance documents bulletins, memos, and even blog posts that do not go through the notice-and-comment rulemaking process, as required by the Administrative Procedure Act, yet carry regulatory weight.118

In short, without changes in the law, stated intent of Congress, or a formal rule, the SEC has been sending signals through enforcement actions and statements from officials that new issuers of cryptocurrency may be required to go through the same cumbersome securities registration process as do issuers of stocks and bonds.

The SEC has been regulating products under its jurisdiction, such as exchange- traded funds, or ETFs, more stringently if they involve cryptocurrency. Since 2017, the commission has rejected proposals for more than 10 Bitcoin- based exchange traded funds, sparking a strong dissent in 2018 from Commissioner Hester Peirce. Peirce wrote that the SEC’s rejection “signals an aversion to innovation that may convince entrepreneurs that they should take their ingenuity to other sectors of our economy, or to foreign markets.”119

Most troubling is the SEC’s assertion of jurisdiction over cryptocurrency products that clearly do not fit the definition of a “security” from either Congress or the courts. A 2019 guidance document from the SEC— properly classified as “regulatory dark matter,” since it was never submitted to Congress for review as a rule— states that even in cases where cryptocurrency can be used in a functional market for goods and services, “there may be securities transactions if … there are limited or no restrictions on reselling those digital assets.”120

This overly broad definition of a security could set a precedent for the SEC to regulate not just cryptocurrency, but everyday consumer goods, as “securities.” In an interview for a CEI study, prominent FinTech attorney Georgia Quinn said after reading the SEC guidance, “I think airline miles and retailer points could be considered securities,” noting that some of these items are transferable and therefore could be deemed to have a secondary market. For instance, the website points.com enables users to manage and exchange rewards points, creating what could be deemed a secondary market.121 And then there are the numerous physical goods, from comic books to baseball cards, that are often bought in part as investments and can be sold in secondary markets.

For cryptocurrency and other new technologies to flourish, consumers, investors and entrepreneurs must be protected from the overreach of the SEC. The Trump administration and Congress need to rein in “regulatory dark matter” at the SEC (as well as other agencies) and curb any efforts by the SEC to stretch the definition of “security” beyond recognition.

Furthermore, Congress should update the nation’s securities laws to more clearly and narrowly define federal agencies’ jurisdiction over cryptocurrency.

INFORM Act

The Integrity, Notification and Fairness in Online Retail Marketplace for Consumers (INFORM) Act (S. 3431) would force online marketplaces like Amazon, eBay, and the like to verify the government ID, tax ID, bank account, and contact information of all their third-party sellers that make at least 200 sales amounting to $5,000 or more in one year. Platforms would also be obligated to make that information available to customers. The bill seeks to thwart sales of counterfeit and stolen items online by third-parties, but platforms are already working to solve those problems for consumers.

Just as there is a certain amount of fraud in bricks and mortar retail, there is also fraudulent activity online. But a lack of perfection should not be the rule for when to regulate. Market failure should be the only justification for government intervention.

Retail platforms that host third-party sellers have every incentive to protect their reputations by protecting their customers. eBay has won awards for its cooperation with rights holders to address the sales of fakes online.122 Amazon is the nation’s largest online retailer and Americans rank the company among the most trusted brands.123 That trust is a competitive advantage that Amazon saw fit to spend $500 million protecting in 2019. The retail platform also devoted the efforts of 8,000 employees to combat these problems on its platform last year.124 The company vets new third- party sellers, monitors their offerings, and proactively notifies and even refunds consumers when fraud has been detected. Amazon offers a Brand Registry program,125 a Transparency service,126 a Counterfeit Crimes Unit, and other security services that the company has instituted on its own.127

All of this appears to be money well spent because, according to testimony from Amazon Vice President Dharmesh M. Mehta gave to the House Committee on Energy and Commerce in March, the company prevented 2.5 million suspected bad actor accounts from starting to sell in its online stores, blocked six billion suspected bad listings from appearing, and blocked and repressed 100 suspected fake reviews last year.128 All of this benefits Amazon in preserving its good name, and it benefits consumers by protecting them from fraudulent items and information.

Market solutions are already working to protect consumers. A regulatory bill is not needed.

But worse than being repetitive, the INFORM Act may be harmful. The unintended consequences of the bill include security and privacy concerns with the gathering, storing, and sharing with customers of potentially sensitive information. The best intentions do not prevent the inherent tension between verification and privacy. There is also a chance that these compliance costs could act as a barrier to entry for the next, but still small, eBay or Amazon. The big platforms can afford to comply, but the new guy might find the regulatory hoop cost prohibitive.

Better to let market forces compete for consumers by catering to their preferences. It is already happening to combat fraud online. Let’s hope Congress does not get in the way.

Conclusion

Market solutions, unlike legislation, better lend themselves to address the myriad problems that inevitably arise in a free, competitive economy. The Internet was not initially designed as the mass commercial and consumer medium it is today. If one were to design a commercial network today from the bottom up, it likely would incorporate better authentication. Now that we are in midstream, we wonder if technology can fix its attendant problems, or if law must do it. Either free enterprise or Congress and legislators can set terms, but not both.

There is a role for law. Fraud, falsification, identity theft, hacking, and the like should be punished, but overly burdensome legislation will create legal and regulatory hassles for small businesses—a reason some large firms favor intervention—and the development of newer technologies and services, which is one of the great hidden costs of regulation.

Bad legislation now lays the groundwork for worse legislation later. Embracing regulation and central planning entails embracing collective “solutions” that will be difficult or impossible to correct later. The legislation we actually need would be a bill to prevent many of these misguided proposals.

NOTES

- Elizabeth Holmes and Amy Schatz, “McCain Tech Plan to Continue Hands-Off Approach to Regulation,” Wall Street Journal, August 14, 2008, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB121867827436739337.

- Clyde Wayne Crews, Jr., “Mapping Washington’s Lawlessness: An Inventory of ‘Regulatory Dark Matter’ 2017 Edition,”

Issue Analysis 2017 No. 4, Competitive Enterprise Institute,

https://cei.org/content/mapping-washington%E2%80%99s-lawlessness-2017. Clyde Wayne Crews, Jr., Ten Thousand Commandments 2020: An Annual Snapshot of the Federal Regulatory State, Competitive Enterprise Institute, May 27, 2020, https://cei.org/10kc2020.

- The White House, “President Donald J. Trump’s Historic Deregulatory Actions are Benefiting American Families, Workers, and Businesses,” news release, June 28, 2019.

https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/president-donald-j-trumps-historic-deregulatory-actions-are-benefiting- american-families-workers-and-businesses/.

- Clyde Wayne Crews, Jr. and Adam Thierer, “The Digital Dirty Dozen: The Most Destructive High-Tech Legislative Measures of the 107th Congress,” Policy Analysis No. 423, Cato Institute, February 4, 2002, https://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/digital-dirty-dozen-most-destructive-hightech-legislative-measures- 107th-congress.

- Patrick Hedger, “Consumers to Benefit from Court Decisions to Uphold FCC Restoring Internet Order,” OpenMarket blog, Competitive Enterprise Institute, October 1, 2019,

- Clyde Wayne Crews Jr., “A CES Takeaway: Don’t Fear Robots and Artificial Intelligence, Fear Politicians,” Forbes, January 8, 2017,

https://www.forbes.com/sites/waynecrews/2017/01/08/a-ces-takeaway-dont-fear-robots-and-artificial-intelligence-fear– politicians/#357903107984.

- FAANG is but one acronym, and Netflix sometimes seems misplaced here. Other examples include GAFA (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple) and even MAGA (Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Apple).

- Will Rinehart, “An Ongoing List of Tech Bills in 116th Congress (2019–2020), Medium, March 15, 2019, https://medium.com/@willrinehart/an-ongoing-list-of-tech-bills-in-116th-congress-2019-2020-f3822b2b3182.

- “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, characterized as such by Jeff Kosseff of the U.S. Naval Academy’s Cyber Science department in a book of the same name. Jeff Kosseff, The Twenty-Six Words that Created the Internet (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019).

- On February 27, 2018, the Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act/Stop Ending Sex Traffickers Act (FOSTA-SESTA) package was passed in the House of Representatives by a 388-25 vote. On March 21, 2018, the FOSTA-SESTA package bill passed the Senate with a vote of 97-2, with only Sens. Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Rand Paul (R-KY) voting against it. Roll Call Vote on Passage of HR 1865 SESTA/FOSTA Last Vote of the Day, Senate Democrats, March 21, 2018, https://www.democrats.senate.gov/2018/03/21/roll-call-vote-on-passage-of-hr-1865-last-vote-of-the-day.

- The Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (FOSTA) was the House of Representatives bill and the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (SESTA) was its Senate companion bill. For more, see, Elizabeth Nolan Brown, “Section 230 Is the Internet’s First Amendment: Now Both Republicans and Democrats Want to Take it Away,” Reason, July 29, 2019, https://reason.com/2019/07/29/section-230-is-the-internets-first-amendment-now-both-republicans-and-democrats-want-to- take-it-away/.

- 1996 Communications Decency Act, Section 230, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/47/230.

- “Sites Using Facebook ‘Like’ Button Liable for Data, EU Court Rules,” Euractive with AFP, July 30, 2019, https://www.euractiv.com/section/digital/news/sites-using-facebook-like-button-liable-for-data-eu-court-rules.

- For more on EU Internet regulation, see Ryan Radia and Ryan Khurana, “European Union’s General Data Protection

Regulation and Lessons for U.S. Privacy Policy,” OnPoint No. 245, Competitive Enterprise Institute,” May 23, 2018, https://cei.org/content/european-unions-general-data-protection-regulation-and-lessons-us-privacy-policy.

- Adam Thierer and Clyde Wayne Crews, Jr., eds, Copy Fights: The Future of Intellectual Property in the Information Age

(Washington, DC: Cato Institute, 2002).

- Telecommunications Act of 1996, Federal Communications Commission, https://www.fcc.gov/general/telecommunications-act-1996.

- Charles B. Goldfarb, “Telecommunications Act: Competition, Innovation, and Reform,” Congressional Research Service, June 7, 2007. https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20070607_RL33034_41a165fda09eb9fd0de96374f3425ae4f3276f53.pdf.

- Digital Millennium Copyright Act, Harvard University. Accessed at: https://dmca.harvard.edu/pages/overview.

- Mulligan, Stephen P., Wilson C. Freeman, and Chris D. Linebaugh, “Data Protection Law: An Overview,” Congressional Research Service, March 25, 2019. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R45631.pdf.

- “What is the CAN-SPAM Act?” Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/inbox/what_is_can-spam.

- Goldman, Eric, “The Complicated Story of FOSTA and Section 230,” First Amendment Law Review, April 17, 2019.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3362975.

- Jeff Kosseff, The Twenty-Six Words that Created the Internet (Ithaca; N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2019).

- https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2018/11/8/18076440/facebook-monopoly-curse-of-bigness-tim-wu-interview.

- Jemima Kiss, “An Online Magna Carta: Berners-Lee Calls for Bill of Rights for Web,’” Guardian, March 12, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/mar/12/online-magna-carta-berners-lee-web.

- “Web Pioneer Wants New ‘Contract’ for Internet,” France24, May 11, 2019,

https://www.france24.com/en/20181105-web-pioneer-wants-new-contract-internet. Jamey Keaten, “At Age 30, World Wide Web is ‘Not the Web We Wanted,’” Associated Press, March 12, 2019, https://apnews.com/1a944fcf10c445f2a87fcd5c2d0320e5.

- Guy Faulconbridge and Paul Sandle, “Father of Web Says Tech Giants May Have to be Split Up,” Reuters,

November 1, 2018,

- Office of Congressman Ro Khanna, “Rep. Khanna Releases ‘Internet Bill of Rights’ Principles, Endorsed by Sir Tim Berners-Lee,” news release, October 4, 2018,

https://khanna.house.gov/media/press-releases/release-rep-khanna-releases-internet-bill-rights-principles-endorsed-sir-tim. Todd Shields, “Democrats Eye ‘Internet Bill of Rights’ If They Win the House Todd Shields,” Bloomberg, October 17, 2018, https://www.bloombergquint.com/business/democrats-eye-internet-bill-of-rights-if-they-win-u-s-house.

- “Notable and Quotable: Milton Friedman,” Wall Street Journal, October 6, 2015, https://www.wsj.com/articles/notable-quotable-milton-friedman-1444169267.

- Kari Paul, “Will Americans pay companies to keep their data private? Here’s their answer,” MarketWatch, January 19, 2019,

- Armando Roggio, “DuckDuckGo Attracts Privacy-conscious Shoppers,” Practical Ecommerce, January 24, 2020, https://www.practicalecommerce.com/duckduckgo-appeals-to-privacy-conscious-shoppers.

- DuckDuckGo traffic information, https://duckduckgo.com/traffic.

- Jonathan Ponciano, “The Largest Technology Companies In 2019: Apple Reigns as Smartphones Slip and Cloud Services Thrive,” Forbes, May 15, 2019,

- Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO) remarked in September 2019: “It is time we held them accountable, stood up for the First Amendment, and it is time to stop censorship by these big companies and say that conservative speech is valuable speech and conservatives ought to be able to speak in our society openly, in public, and without reprisal.” https://twitter.com/yaf/status/1156615193385943040.