New Book ECO-FREAKS Reveals Destructive Environmental Agenda

Contacts: Peter Nasaw, (212) 966-4600, Christine Hall, (202) 331-2258

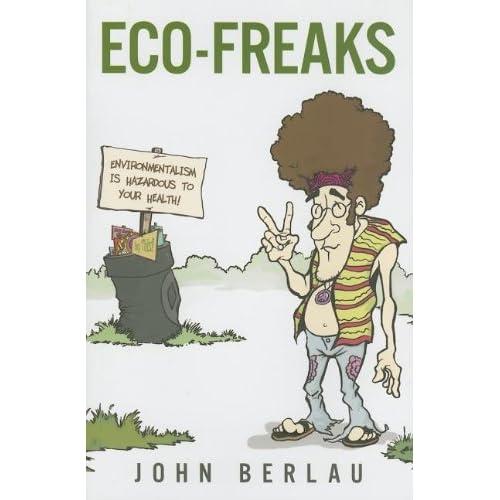

Washington, D.C., November 28, 2006—Rachael Carson’s Silent Spring advice actually killed birds? Trees cause more air pollution than cars? In a new book, ECO-FREAKS, author John Berlau shatters long-standing environmental myths with true, startling revelations.

“Environmentalists have long admitted to using fear to arouse public action,” writes Berlau, who is a policy director at the Washington, D.C.-based Competitive Enterprise Institute. In ECO-FREAKS, Berlau exposes the often tragic consequences of modern environmentalism. From the banning of DDT to the collapse of the levees in New Orleans, environmentalists have used an idyllic image of “nature” to pursue a radical, anti-human agenda.

In ECO-FREAKS, the author shows how environmentalism has put us all in danger: The banning of DDT has made more people sick; the banning of asbestos has allowed more buildings to catch fire; and exaggerations about global warming jeopardize automobile safety. Environmentalists also played a role in the devastation wrought by Hurricane Katrina by blocking the federal government’s plans to build giant floodgates on Lake Pontchartrain. Berlau urges policymakers to abandon such destructive policies and embrace a practical conservation ethic, one that would better protect public health and wildlife.

CLICK HERE to request a copy for review.

CLICK HERE to buy the book on Amazon. (ISBN: 1595550674)

AUTHOR BIO

John Berlau is Director of the Center for Entrepreneurship. Previously, he was the 2004-2005 Warren Brookes Fellow. He has written for many publications, recently serving as an investigative writer on the staff of Insight magazine. The National Press Club awarded him its 2002 Sandy Hume Memorial Award for Excellence in Political Journalism for his series of stories in Insight about the conflicts of interest of now-former IRS commissioner Charles Rossotti. He is a former Washington correspondent for the newspaper Investor’s Business Daily. He has also written for Reader’s Digest, USA TODAY, USA Weekend, the Wall Street Journal, the New York Post, Reason, The New Republic, National Review, and The Weekly Standard, and RAZOR.He graduated from the University of Missouri in 1994, with a double-major in journalism and economics. He was a media fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University.

****************** Q and A with author John Berlau ******************

1. What do you have against environmentalism?

I am a conservationist. I believe in wise stewardship in harvesting and conserving natural resources and in good management of the beauty of the landscape.

The environmental movement of today, by contrast, is preservationist, obsessed with preserving and restoring a landscape unaltered by humans that may have never existed. It operates on the premise that untrammeled nature is always benign. Paradoxically, because we have been so successful at overcoming nature’s ravages, too many people attribute everything from rough weather to diseases — forces of nature that have plagued the world for centuries – to human activities. To focus on the “environment,” the “planet”, or the “ecosystem” obscures and often worsens specific threats to humans, animal, and plants. And many times, environmentalist prescriptions have been in conflict with public health.

2. But isn’t global warming threatening public health by causing a resurgence of diseases like malaria?

This is just one instance I’ve found where environmentalists blame some man-made threat for a problem largely caused by their own misguided policies. The primary cause of the malaria resurgence is the ban of DDT, which was demonized by Rachel Carson’s influential Silent Spring yet remains the most effective insecticide for use to control malaria-carrying mosquitoes.

Malaria is nothing new to Nairobi. Outbreaks occurred there in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. What got malaria “under control” there as well as in other areas, including parts of the United States, was the introduction of DDT after World War II. The World Health Organization specifically credited DDT use for preventing a malaria epidemic from reoccurring there after a flood in the early 1960s. But after DDT use stopped due to environmental pressure, malaria returned in many places where it had been nearly eliminated, such as Sri Lanka. And DDT was banned before a malaria eradication program could be launched for most of southern Africa, where the disease now kills to million a year. In fact, the World Health Organization recently just reversed its long-held policy and now encourages DDT use there to combat malaria.

3. But DDT was once nicknamed “Double Death Twice” in the popular press. What happened to people exposed to higher than normal amounts of DDT?

Studies show they turned out fine, and the experiences of some folks makes me wonder if exposure to DDT actually prolongs your life. Joseph Jacobs was a chemist directing the effort to mass-produce DDT to protect World War II soldiers from insect-borne disease. In the rush to get the first shipment out the door, a valve that Jacobs happened to be standing under was accidentally opened, and Jacobs was soon covered with hot DDT. Jacobs did indeed die – more than 60 years later at the tender young age of 88. He would go on to build a top engineering firm, write books, and have a family. But he always considered his role in the early production of DDT as one of his greatest accomplishments. The story is same for others, including one man who is still alive at 97.

4. But what about birds and forests. Doesn’t DDT do a lot of damage there?

DDT can be harmful if used in excess, but application of DDT has also saved many trees from insect infestations and may be partly responsible for an increase in bird populations. Starting in the late ‘40s, it was sprayed on elm trees to successfully stave off predatory beetles spreading Dutch Elm disease. After DDT was banned, the U.S. population of elm trees fell by more than half, and many American towns have few of the elms that once lined their streets. DDT also saved Oregon’s “old-growth” Douglas fir trees, home for the celebrated spotted owl, from devastation by tussock moths in 1974.

In some of the instances where DDT was alleged to have killed birds, other factors – from excess hunting to mercury poisoning – were more likely the real culprits. Further, the bird population would often increase in areas spread with DDT as there were fewer insects to spread bird diseases. Ironically, today the mosquito-borne West Nile virus is killing many of the birds – including robins, condors, eagles and peregrine falcons – alleged to have been harmed by DDT. Yet greens still oppose most spraying programs that use any type of pesticide to fend off mosquitoes.

5. The word “asbestos” today has a dangerous connotation. Yet you credit asbestos with saving hundreds of thousands of lives. Why?

Donald Trump said, “A lot of people in my industry think asbestos is the greatest fireproofing material ever made.” Fire testing organizations such as the National Fire Protection Association have consistently given asbestos materials a zero flame-spread rating, which means it has no ability to spread flame under any circumstances. Before asbestos was widely used, it was not uncommon for a fire in a school or theater to kill, dozens, and sometimes hundreds of people. After asbestos, these types of fires disappeared overnight. Fred Astaire sang the praises of asbestos in the classic 1930s song, “I won’t dance.” And my book documents how lack of asbestos added to the tragedies of the World Trade Center attacks in 2001 and the fire at The Station nightclub in Rhode Island in 2003

6. Is overdevelopment the cause of the increase of automobile collisions with deer?

Not primarily. Laws and polices, influenced by environmentalists, are actually moving the “wild lands” closer to us. Since the ‘50s, only 26 percent of former farmland has been urbanized. Much of the rest has become new forest land in a phenomenon called reforestation. The share of forested land increased from 50 percent to 86 percent in New Hampshire.

And policies in these new and old forests are harming humans and wildlife. Bans on cutting down most “old-growth” or mature trees results an abundance of big trees with leaves that deer can’t reach. The trees also block sunlight for other vegetation that deer could eat. This necessitates deer “eat out” more often, heading through traffic to rummage through gardens.

7. How did the environmentalists make New Orleans more susceptible to flooding?

The Army Corps of engineers intended to construct floodgates to close off water from Lake Pontchartrain during storms. A lawsuit by the local environmental group Save Our Wetlands, assisted by the national Environmental Defense Fund (now Environmental Defense), sued the Corps of Engineers, saying that gates could threaten some fish species. The U.S. Attorney warned the federal judge that a delay could kill thousands of New Orleanians in a hurricane. Nevertheless, in 1977, a federal judge stopped the project.

The Corps had already done an environmental impact study that was approved by the EPA. A second study satisfying the judge’s requirements, such as examining the mating habits of certain fish, may have taken ten years, the Corps feared. So the Corps went with what was regarded as the second-best option, building higher levees.

8. Why should liberals and leftists be skeptical of the environmental movement?

I disagree with liberals on most issues, but I do believe that many of them care deeply about people. So they should be alarmed when environmental leaders put the welfare of animals and plants ahead of people.

Liberalism and environmentalism have only been strongly connected for about 40 years. Franklin D. Roosevelt had no particular fondness for pristine wilderness. He boasted proudly of the dams he built and proclaimed proudly, at the dedication of the Hoover Dam (then called the Boulder Dam), that humans were “altering the geography of a whole region” that had previously been “cactus-covered waste.” In the 19th century, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels disagreed vehemently with the original population doomsayer Thomas Malthus. Sounding much like modern population control critic Julian Simon, Engels wrote that “it is ridiculous to speak of overpopulation,” because the progress of “science … is just as limitless and at least as rapid as that of population.”