Use the Congressional Review Act to strike rules not reported to Congress and GAO

Photo Credit: Getty

Significant attention is likely to turn to Joe Biden’s ambitious regulatory agenda before summertime.

That’s because rules the administration finalizes “late”—during the last 60 in-session days of the 118th Congress—are potential targets for expedited reversal via Congressional Review Act “resolution of disapproval” if there is a change in administration in 2025.

At the moment, for example, there are 232 rules under production acknowledged by the administration to weigh at least $200 million in annual impact that are well worth Congress’s attention.

Of course, any of these rules agencies fail to finalize during 2024 will simply be frozen in January 2025 if someone takes Biden’s place, as is the norm. But those finalized late in the year rather than early are vulnerable to being smacked by the “ROD.”

Less known, though, is that Congress might have even more options than this to disavow some of the larger or more controversial rules that squeak in before the 60-day CRA window closes this year.

The Government Accountability Office’s website FAQ reminds us that “The CRA requires an agency promulgating a rule to submit the rule to Congress and GAO before it can take effect.”

Accordingly, the GAO maintains an online database of those submitted rules (as well as the subset of “major rule” reports the CRA also requires). There’s even an official form for these submissions.

As it turns out, though, that mandatory rule submission doesn’t always happen, and this lapse can matter for supervising the Biden agenda if Congress insists upon it.

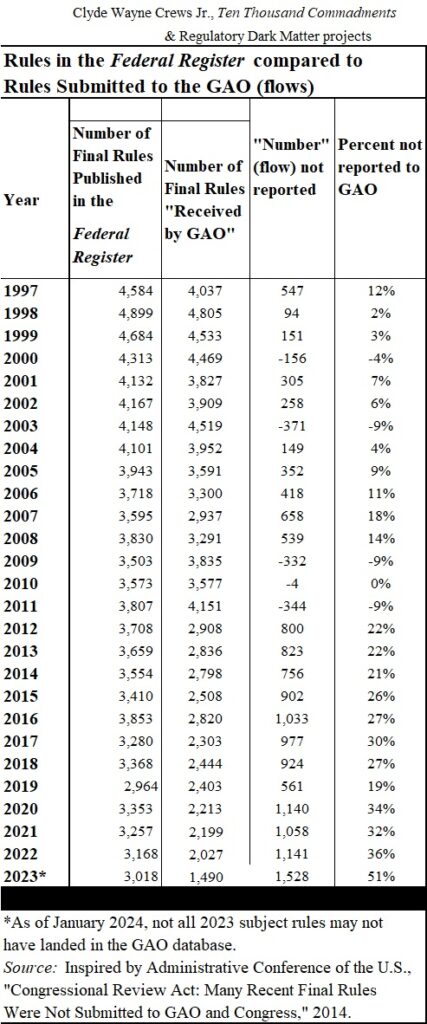

A 2014 Administrative Conference of the United States report “Congressional Review Act: Many Recent Final Rules Were Not Submitted to GAO and Congress” found that many rules were in fact not being properly submitted as required. Among other inquiries, the ACUS survey compared the full population of rules finalized in the Federal Register with those that had been reported to GAO.

Most but not all agencies rules (as well as guidance documents, and that’s another big story) are required to be submitted. At the time of the ACUS report, the CRA-compliant proper percentage submitted to GAO appeared to hover around 88 percent, but ACUS found slippage as the rate of submission fell to only around 71 percent of rules by the time 2013 rolled around.

There remains no readily available direct one-to-one mapping of covered rules reported or not-reported to GAO to compare with rules finalized in the Federal Register (requiring such a mapping would be an appropriate reform). But in the update below, the concern highlighted by ACUS seems to have worsened. By gross counts in the GAO database and in the Register, more covered rules than ever before are likely still not being properly reported to GAO.

In each of the years 2020, 2021 and 2022, over 30 percent of rules in terms of flow were not reported to GAO by this reckoning. Conversely, the early days seemingly may have done somewhat better than the initial ACUS investigation found since the “received” component of rules has retroactively increased compared to the “submitted” designation ACUS employed then (moreover, it is not uncommon for us to find federal regulatory archival databases to rewrite themselves slightly). But matters seemingly did worsen from 2012 onward with over 20 percent unreported.

The subset cannot be bigger than the whole, but the chart does show “overages” in some of the GAO counts compared to the full set represented by the Federal Register in some calendar years. This is perhaps explained by GAO posting in batches or by some rules being applied to an adjacent calendar year, and lags in when rules land at GAO and when they get posted by in the rules database. In the future, more direct mapping can help with this.

That “only” 51 percent for 2023 were reported is noteworthy, but that is likely to improve considerably as it may be that some of 2023’s received rules are not yet embedded in the database.

But in any event, since 2012, hundreds, sometimes over 1,000 rules a year are not being reported, at least ostensibly so in terms of Federal Register “excess” over the GAO database. Congress should investigate what’s really happening, and could request clarification from GAO itself, or inquire with Congressional Research Service about delving a bit into the current status of CRA compliance.

In any event, the seeming non-compliance, in GAO’s own interpretation, implies a significant population of “invalid” rules are out there now, and that some may yet reside among Biden’s newest tranche. Even those finalized before the 60-legislative-day deadline would nonetheless be problematic by this interpretation.

This non-compliance concern is greater than the chart implies. While one can easily inspect the GAO rules database and make a rough comparison of reported/total flows, that’s only one half of the equation as far as CRA reporting requirements go.

There is no readily available capability for tracking the equally important reporting or lack thereof to both houses of Congress. There is no form, no agreed-upon process for readily evaluating CRA compliance in this respect. One can observe some non-definitive executive communications in the Congressional Record, but nothing actually archival or official exists to certify compliance with the CRA. That implies still more “invalid” rules are out there.

To be sure, many of the rules implicated in non-compliance are “routine or informational,” but some could already and may later likely include Biden’s $200 million ventures. Furthermore, even allegedly routine and informational rules in fields such as health care, retirement, insurance and aviation are more than merely routine when they displace what would have otherwise been private activity.

A remedy for reporting failures, after better defining what counts as success, would be a legislative patch to require prominent documentation (for example in the Federal Register and in the Congressional Record) of the reporting of covered rules to both GAO and to Congress. Guidance must also be included, since it is now exempt from disclosure altogether, yet is subject to the CRA.

Along with its likely plan of attack for rules not finalized within the CRA legislative-day window, the Congress should affirm this year that finalized but unreported rules will be considered suspect if not deemed invalid altogether. The occasional approach of requesting a GAO declaration that some particular instance is a “covered rule” before embarking upon a ROD proceeding is not a stance capable of restraining administrative state growth.

At least according to the letter of the law, unreported rules are invalid. If the laws says so, Congress can believe it since it wrote the law in the first place—and try opening the window for streamlining wider than 60 legislative days.