Climate Disclosure’s Triple Threat

SEC, EU, and California regulators pile it on

Introduction

Financial regulators from the US federal government, California, and Europe have each recently adopted climate disclosure rules for companies. These environmental, social, and governance (ESG) mandates present major challenges for many US corporations caught between two or even three overlapping regulatory schemes.

Depending on their locale, US companies may be forced to grapple with:

- Millions of dollars in domestic and/or international compliance costs to document their carbon footprint;

- Multi-layered reporting requirements on firms for climate-related data that are of little interest to most retail investors;

- Mandatory requirements that threaten to upend the phenomenon of voluntary climate reporting;

- Unequal and noncomparable climate reports from companies that perceive external risks differently;

- Regulatory regimes that discount material differences across firms when imposing standardized reporting requirements;

- Voluminous ESG mandates that undercut corporate and investor choice and threaten to flood investors with what has been called “climate disclosure spam”;

- Conflicting demands of multiple regulatory jurisdictions, each demanding similar, but not identical, streams of environmental data;

- Widespread regulatory confusion among firms over what risks are materially relevant and therefore necessary for adequate disclosure; and

- Forced compliance from the European Union (EU), despite having no definitive legal basis for compelling ESG disclosures from American firms.

If all three regimes go into force, many large US firms will suffer a triple regulatory compliance burden. From a policy perspective, the greatest cumulative threat from these mandates is that they will critically deter business growth in American and European markets, while failing to generate meaningful environmental data that is consistent or comparable for investor choice.

What each rule requires

The Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) climate rule seeks to compel public corporations to produce consistent and comparable disclosures of material climate risks. The rule is the most restricted in scope, applying to only publicly listed domestic firms. Unlike California and the EU’s rules, the SEC’s rule adopts a limited greenhouse gas (GHG) scope reporting system. It requires large and accelerated filers to disclose any material information on their direct and indirect emissions.

However, the SEC’s rule is more multifaceted than its peers by imposing 12 categories of detailed disclosures on regulated firms. Certain businesses will need to include detailed footnotes on the physical effects and capitalized costs of severe weather events to their operations. The rule is broad in its expectations, as corporate boards will need to assess how climate related risks affect the firm’s business model, management strategy, and financial future.

California’s climate reporting rule was adopted with a similar aim of obtaining consistency and comparability among climate disclosures. The difference is that California’s rule targets both large private and public firms for their various emissions activities. Because of this, California’s rule is broader in scope, projected to ensnare roughly twice as many companies as the SEC’s rule. Its GHG reporting law is also broader than the SEC’s rule, including a Scope 3 provision that compels firms to disclose data on their value chain emissions.

Additionally, California’s rule is unique in that it requires firms to justify the emission reduction goals outlined in their carbon credit trading schemes. California would requires firms to account for any and all climate-related risks to business activities, irrespective of materiality.

Last but not least is the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). like California’s rule, CSRD applies to both public and private firms. The CSRD reserves the broadest jurisdiction, mandating climate reporting for all companies that do business across EU member states, so long as they meet specified financial thresholds. Similar to the SEC and California, the EU’s reporting requirements are most stringent toward large firms. The EU is far stricter on its assurance requirements relative to the SEC, as all firms will be required have an auditor verify their sustainability reporting.

Like the SEC’s 12 disclosure categories, the EU’s rule imposes 12 standards of reporting requirements that span a wide range of ESG matters. The EU’s rule goes beyond the SEC and California by imposing a complex “double materiality” requirement for all reporting firms, something untested in any US financial regulation.

Failure to properly navigate this complex web of climate reporting may trigger penalties in one agency’s jurisdiction, while otherwise being permissible in the other jurisdictions. This undermines the rules’ ostensible focus on establishing consistent climate reporting across regulated firms. As University of Maryland Professor Michael Faulkender warned, “when a standard like ESG is murky in the eye of the beholder, it’s impossible to enforce,” but many attempts will be made.

The trouble with dueling mandates

Forcing corporate compliance with overlapping, costly, and confusing ESG mandates is unwise and likely not feasible for three reasons.

First, the materiality requirements within California and the EU’s climate mandates are redundant for public firms in the US. This is because the SEC’s principle-based reporting standards already require public firms to disclose any material information to investors.

If climate risks actually exist and are deemed material by the reporting firm, investors will be made aware of any fluctuations in the company’s financial health or, if needed, by a separate sustainability report. Regulatory bodies from the US, EU, and California need only look at existing corporate financial disclosures that contain what is materially relevant to investors, rather than compelling firms to submit additional climate disclosures.

Second, despite their unified goal, it is impossible for all three climate rules to generate consistency and comparability of disclosures. This is because regulatory bodies set varying thresholds for materiality, environmental reporting standards, and categories of disclosure, making apples-to-apples carbon comparisons impossible. Companies also differ widely about what climate risks are deemed to be materially relevant for their investors. A company’s climate disclosure may look vastly different for California than it does for the EU or the SEC

Finally, the cumulative compliance costs for the three rules vastly outweigh the benefits of expanding corporate transparency. In the US, retail investors typically do not base their investment decisions upon disclosed ESG data.

Academic research backs this up, as a 2021 paper reveals that corporate “ESG disclosures are irrelevant to retail investors’ buy and sell decisions.” The study compares the preferences of retail investors to a firm’s ESG-related press releases and its financial announcements. The researchers find that investors “adjust their portfolios substantially less on days with ESG press releases relative to days with non-ESG press releases.”

In other words, the study demonstrates that investors adjust their portfolios only in the face of financially material developments at the firm rather than during uneventful periods with ESG disclosures. Such findings ought to have signaled to the SEC that, despite all the hype of mandatory ESG disclosures by select investment managers and large firms, the actual retail investors don’t base their decisions on ESG information. While subjective sustainability factors are meaningful to a certain subset of investors, most do not deem them to be equal or superior to traditional, objective financial factors. As such, the impact of the three climate rules will be the heightened compliance costs borne by all affected companies for the benefit of an almost immeasurably small group of market participants.

The SEC and EU’s conflicting climate rules

At the national level, the SEC has recently passed a final rule mandating that public companies report any material climate change risk factors in their annual and quarterly disclosures. The SEC’s rule is more flexible than the EU’s rule in that it does not ground its requirements in any approved ESG reporting standard.

Rather, it is loosely based on recommendations proposed by the Taskforce for Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). The Financial Stability Board (FSB) created the taskforce in 2017 as an informal body of financial professionals and organizations, seeking to direct businesses globally to transparently disclose their climate change risks.

The most controversial element of the rule is the GHG component, requiring large reporting firms to quantify their direct (Scope 1) and indirect (Scope 2) emissions.

The SEC’s final rule fails to justify the need for compulsory climate disclosures of GHG data. Nowhere in the 885-page rule do SEC officials cite examples of investors being defrauded by a company’s misleading GHG data or perceived climate risks. The SEC should have properly justified its climate rule in advance by revealing concrete examples of greenwashing or climate reporting fraud. In the absence of clear fraud, Congress should repeal the SEC’s climate rule and honor a firm’s decision to voluntarily provide GHG emissions data.

Climate change is not the only area where compliance demands of multiple jurisdictions present a threat. Emergent artificial intelligence (AI) technologies face similar regulatory prospects, being “sandwiched between the regulatory requirements of the European Union (EU) and those of California,” according to Cato Institute analyst Jennifer Huddleston.

The EU has already imposed its own data privacy mandate on US firms in 2016. Known as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), this controversial initiative seeks to strengthen and modernize data protection and privacy within EU member states. By extension it would police the transfer of data from local firms to countries beyond its borders and undermine the free movement of such information. This includes regulating US-based companies that produce advertisements targeted at European citizens.

The EU lacks the authority to enforce the GDPR principles on companies beyond its members’ boundaries. Similarly, GDPR may contain invasive provisions about monitoring data protection that will directly conflict with data privacy laws in the US, the latter of which domestic firms are obligated to respect.

The EU not only suffers an enforceability limitation on the data transfer of US firms via the GDPR, it also cannot usurp existing US data privacy laws nor compel US firms to forsake their own internal data protection policies. The GDPR’s jurisdictional conflict over data privacy raises an important constitutional problem that the EU and California’s climate rules may also trigger: the Commerce Clause of the Constitution states that only the US Congress shall have the power “To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States.”

The GDPR’s intrusive data requirements for US firms are like the CSRD’s invasive climate-reporting requirements for US firms. The EU’s CSRD poses similar jurisdictional problems when seeking to hold non-EU regulated US firms in compliance. We see this “regulation by extension” for CSRD-specific provisions and generally for its Scope 3 mandate, which California’s rule also shares. In the US, Scope 3 introduces a dangerous snowball effect for US firms, as multiple states seek to mimic California. The more states that enact Scope 3, the greater the number of affected firms located outside of the enacting states will be.

With the prospect of multiple states like Illinois, Minnesota, and New York adopting competing climate disclosure rules, this runs the risk of a federal court invoking the Commerce Clause to prevent state or local regulatory interference in business transactions across state lines. California’s Scope 3 mandate, in particular, threatens to violate the Commerce Clause by forcing a host of private firms within and outside of the state to comply with the GHG value-chain emissions reporting requirements.

The EU’s climate mandate takes this a step further by threatening to assert jurisdiction via transatlantic commerce. The EU rule’s Scope 3 mandate essentially displaces congressional authority over regulating commerce by compelling the disclosure of GHG emissions from US-based firms who are partnered with EU-regulated entities.

The SEC’s rule imposes 12 broad new categories of corporate disclosure for climate change risks. This extends to board and managerial awareness of environmental factors affecting business decisions and financial performance.

The SEC’s rule was scheduled to go into effect on May 28, 2024, with a phased process for large firms to their climate reporting to the SEC by January 2025. That was before the SEC halted implementation of the rule in response to a whirlwind of lawsuits by opposing parties. The fate of the rule remains uncertain as the Eighth Circuit Court reviews consolidated challenges to it in Iowa v. SEC.

The EU finalized its climate reporting law—CSRD —in January 2023. Unlike the SEC’s only implied goal to direct investment toward corporate sustainability, the EU’s rule is more direct. This is because the CSRD was adopted as a critical component to advance the “European Green Deal,” a broad set of programs seeking to slash GHG emissions across EU member states, hold companies publicly accountable for their ESG impact, and constrain corporate investment exclusively to renewable energy. The ultimate aim of the European Green Deal is to ensure that Europe becomes the first net-zero continent by 2050.

Troy University Professors Alex Mendenhall and Daniel Sutter describe the EU’s ESG reporting requirements as part of a complicated web of regulations. This regulatory web fosters a concerning alliance between EU member states, quasi-governmental bodies like EFRAG, and EU directed entities to fully drive stringent ESG reporting requirements on private companies absent their input.

As consequence, “the State and supranational institutions, such as the European Union, play a crucial role in … supporting the ideology for legitimising [corporate social responsibility] reporting” without corporate consent or contribution. Government regulators, rather than private interests, are the primary driving force behind mandatory ESG reporting in Europe. The same can be said for climate reporting mandates by US regulators like the SEC, as private markets are being coerced into accepting sustainability disclosure as law in absence of any real market benefits.

Prior to the SEC’s climate disclosure rule, public companies were the primary determinants of the material information to disclose to investors. Corporate leaders provided such disclosures to satisfy the financial concerns of their investors. The SEC has steamrolled this principle-based disclosure framework to impose an arbitrary category of non-financial environmental information that must be disclosed.

This rule will overwhelm the average investor with waves of climate data, overshadowing most of the meaningful information that investors seek to know about their financial stake in the company. This over-disclosure of secondary information combined with the heightened compliance costs, confusion for investors, and enhanced paperwork almost certainly exceed the ostensible social benefits.

Sustainable disclosures have been a topic of discussion among EU officials since the 1990s, the result of sustained lobbying by climate activists. The CSRD represents the latest iteration of the EU’s climate reporting apparatus. The CSRD is intended to build upon the EU’s pre-existing Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD).

The 2014 NFRD was the first EU mandate to require large public interest entities (PIEs) to report non-financial information as part of their disclosure obligations. The CSRD goes beyond the NFRD in several important ways: CSRD has a broader scope that reaches many unlisted enterprises, it requires a third-party auditor, and it requires environmental reporting that is independent of the firm’s annual financial disclosure.

In essence, CSRD is NFRD 2.0, imposing a more aggressive climate reporting framework with far greater reach in response to perceived shortcomings. Some of the most notable of these include: only 20 percent of companies relating their climate risks to their financial, operational, or strategic impacts; fewer than 30 percent of reporting firms failing to explain how materiality of the reporting information was established; and companies integrating their nonfinancial ESG report within their pre-existing financial report. The CSRD contains provisions that are designed to mitigate each of the specified issues with the NFRD.

The NFRD is not unlike the SEC’s climate rule. They each represent the first set of policies for compelling corporate nonfinancial information in Europe and North America, respectively. The SEC and NFRD are also more passive and reserved about certain disclosure requirements compared to the CSRD, which forces most large businesses and all EU-listed firms (including small and medium) to provide strict auditing and assurance reports as part of their overall compliance.

And while the SEC’s rule simply requires the disclosure of pre-existing GHG reduction targets, the EU’s CSRD forces firms to set baseline GHG reduction targets and justify their progress toward reaching said targets. The CSRD erases the corporate discretion of thousands of European and US firms by forcing them to report climate-related financial risks, sustainability goals, and climate mitigation strategies in their financial reports.

Both the SEC and EU’s climate mandates seek to establish a wide-reaching, standardized system of corporate climate reporting that is comparable for investors. However, thanks to significant regulatory disparities, companies are saddled with two competing and at times contradictory standards.

Perhaps the most glaring contradiction between the SEC and EU rules is the diverging set of standards for reporting the impact of GHG emissions. The SEC’s rule requires certain large companies to report their Scope 1 (direct emissions) and Scope 2 (indirect emissions) only if they are deemed to be material. By contrast, the EU requires US subsidiaries in Europe to disclose Scope 1-3 emissions regardless of the perceived materiality and to also justify the reported items through a novel double-materiality disclosure (more on this later).

Both rules require mandatory reporting of GHG emissions, corporate sustainability practices, and explanations of what climate-related risks affect the firms’ activities. However, the rules carry different reporting standards and thus different definitions for how companies should disclose their climate risks. The EU’s mandate is more restrictive and invasive than the SEC’s, requiring all registrant companies to adopt the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS).

The SEC’s rule does not formally adopt or impose any international reporting standards. Instead, it resembles the Financial Stability Board’s (FSB) now-superseded Taskforce for Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) by adopting a similar definition for companies to use when assessing their potential climate-related financial risks. Under the SEC’s rule, companies enjoy more leeway to align with the TCFD’s reporting standards or adopt a similar standard, such as the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), which officially replaced the TCFD in the fall of 2023.

These differences in reporting standards and disclosure requirements undermine the SEC and EU’s shared vision for consistency and comparability across climate disclosures. Moreover, a single, mandatory standard of evaluation has some drawbacks.

This is because multiple competing and evolving voluntary frameworks are more likely to serve the interests of the minority of investors interested in climate reporting better than a single unchanging system. Hence, regulators should preserve the status quo of voluntary reporting based on a company’s standard of choice. Different companies assess different climate risks and compliance with one rule won’t satisfy, and may even contradict, the specified standards of another.

Indeed, standardized climate disclosures are a regulatory fiction. The informational relevance of such disclosures will vary widely among US public companies, while diverging sharply between jurisdictions in the US and EU that are subject to different environmental laws and materiality expectations. This undermines an investor’s ability to cross-compare companies based on objective financial criteria, as the EU’s environmental performance principles don’t reflect the SEC’s environmental transparency goals, despite sharing a broad vision.

This is the case even before considering that climate policy plans are fundamentally forward-looking. In fact, each firm’s assumptions and predictions about weather trends multiple decades in the future can never be adequately standardized.

As Commissioner Hester Peirce stated in a public rebuke of the SEC’s climate rule: “It will require reliance on third-parties and an array of experts who will employ their own assumptions, speculations, and models. How could the results of such an exercise be reliable, let alone comparable across companies or even consistent over time within the same company?”

With the unworkability of these climate mandates in mind, let us now examine some enforceability barriers that EU and SEC regulators will likely face.

EU’s extraterritorial disclosure ambitions

A core issue with the EU’s CSRD mandate is in how it seeks to extend foreign regulations on US-based firms. For instance, the EU’s Scope 3 and double-materiality requirements will ensnare US parent firms by requiring they share GHG data along their value chain and how their activities factor into the subsidiary’s assessment of materiality. In essence, the CSRD’s regulatory reach will extend across the Atlantic and require US firms that were formerly unregulated by the EU to comply.

The CSRD’s reporting requirements capture US firms that are listed on a European financial market, or subsidiaries owned by US-based firms, so long as they generate €150 million in revenue across EU-regulated markets. While US-owned subsidiaries may be subject to the EU’s mandate, given their physical location, their parent firm cannot be compelled to acquiesce to the CSRD. Similarly, some US companies may list securities on an EU regulated market without actually maintaining a physical presence in the EU, as their services may be conducted entirely online.

To meet the European Green Deal’s 55 percent GHG reduction benchmark by 2030, EU member states will aggressively pressure companies to set goals for achieving net-zero carbon output. Similar to the SEC’s rule, the EU’s ESRS require firms to report their climate change mitigation strategies and provide details on how their carbon offsetting programs sufficiently advance a net-zero objective.

EU member states will be empowered by law to crack down on regulated companies for any perceived failures or flaws in their reporting. By contrast, the SEC relies on vague provisions of its authorizing statutes to argue that Congress entrusted the agency with a broad disclosure capacity that encompasses environmental, rather than purely financial, factors.

The EU’s mandate is broader in reach than the SEC’s rule. It applies to any firm with European subsidiaries that list securities on an EU-regulated market. Its wide-reaching reporting requirements will even ensnare non-EU companies that conduct at least €150 million in revenue on the EU market.

Large companies with more than 500 employees must issue their annual EU sustainability report beginning in 2025. Similar to the SEC’s climate rule, where smaller firms enjoy a phased-in compliance date for reporting their disclosures, the EU allows small and medium firms to begin reporting in 2026. Such firms also can op-out of reporting until 2029. Non-EU parent companies must begin reporting in 2028.

The regulatory entanglement of Scope 3

Each of the three rules imposes a set of scope reporting requirements. The EU and California impose stringent requirements for firms to disclose their Scope 1-3 emissions data, while the SEC only requires Scope 1-2 reporting in certain contexts. Scope 1 represents a firm’s directly produced emissions from operations, Scope 2 represents a firm’s indirect emissions from purchased energy, and Scope 3 provides a firm’s value chain emissions across production with third parties.

The EU’s reporting mandate encompasses a Scope 3 requirement that compels reporting of GHG emissions produced from activities across each regulated EU company’s value chain. Value chain refers to the range of procedures and steps a company undergoes to produce and transport a product. Many firms rely on private partners as links of support along their value chain. These partners help provide the service, create the product, and deliver these to customers. These emissions must be captured from the third-party firm’s activities when conducting business with the regulated firm, such as the manufacturing, transportation, and product development.

By contrast, the SEC’s rule compels only disclosures of direct emissions by the public firm (Scope 1) and indirect emissions from purchased energy (Scope 2). The agency chose to eliminate its Scope 3 provision of the rule when faced with significant industry pushback.

One objection to the SEC’s initial Scope 3 proposal was that it would force novel regulatory burdens on otherwise unregulated private firms that have business relationships with registrant firms. This regulation by extension underscores one of the chief issues with the EU and California’s Scope 3 mandates. Private firms that once enjoyed little to no disclosure obligation will now be weighed down by the same compliance burden as public firms.

As the US public markets become increasingly regulated and costly to enter under current SEC leadership, many private entities, particularly farmers and ranchers, were opposed to Scope 3 compliance as a condition of doing business. Despite the SEC’s removal of Scope 3 on paper, some observers are not convinced that it is completely gone. There are concerns that public firms with preexisting sustainability goals (e.g., GHG reduction targets) will still be required to gather emissions data from their private partners for disclosure. Thus, the SEC’s rule may invite a backdoor, or informal, Scope 3 mandate that will be inescapable for environmentally conscious companies. In addition to this potential backdoor Scope 3 requirement, many public US firms will still need to disclose their Scope 3 emissions to their subsidiaries via the CSRD.

Unlike EU and California officials, the SEC heeded some of the public comment concerns about Scope 3 reporting. For instance, third parties that decline to provide such information may remove their reporting obligations by severing business ties with registrant firms entirely. Private companies might choose to do so because they do not want to be named a party to an SEC enforcement lawsuit against the registrant firm for failing to meet its Scope 3 requirement. In essence, Scope 3 greatly elevates a reporting firm’s litigation risks while threatening certain partnerships that are sensitive to regulations.

The SEC at least recognized the potential market disruption posed by the Scope 3 mandate and heeded public opposition in removing it from the final rule. The EU retains its Scope 3 mandate despite the prospect of a more expensive and widespread regulatory impact on the many thousands of private firms doing business with EU-regulated companies.

Both the SEC’s rule and EU’s mandate not only require scope emissions reporting, they also demand that companies report on how they will engage in GHG reduction or other forms of climate change mitigation. Essentially, government regulators are seeking to drive corporations to decarbonize their activities, forcing their hand to mitigate their reported risks through an arbitrary litmus test. In the US, critics of the SEC’s rule charge that they are pursuing this absent any legitimate legislative authority.

This means that many publicly traded firms housed in the US will need to meet the EU’s regulatory requirements for disclosure, even though they are not directly subject to EU law. Estimates show that approximately 50,000 firms are currently caught in the CSRD’s regulatory dragnet, including an estimated 3,000 US firms. The EU’s reporting requirements extend to many European based subsidiaries of US companies.

This regulatory framework is problematic, since the subsidiaries will extend the CSRD’s compliance burden over to the US-based parent firm simply by circumstance of their location. The subsidiary’s obligation to satisfy millions in CSRD compliance costs and potential monetary penalties for noncompliance will trickle up to the parent US firm and its shareholders.

Additionally, the subsidiary will need to coordinate with the parent firm when gathering comprehensive data on its climate-related risks, energy usage, sustainability efforts, and proposed targets for reducing alleged environmental harm over time. This will force subsidiaries to shift much of this hefty administrative and paperwork burden onto the parent firm, which will likely already be grappling with domestic compliance hurdles within the SEC’s and/or California’s climate mandates.

The EU’s heavy focus on qualitative data from regulated firms will also place a heavier burden on firms gathering internal data across many different departments that otherwise were not gauging their climate risks across the entire business. This places US firms at a severe learning disadvantage, since the domestic climate disclosures like the SEC’s rule don’t require as high degree of detail, cross-departmental collaboration, or personalization in what is disclosed.

Finally, under the EU’s Scope 3 provision, the parent firm may need to share its GHG emissions data with the subsidiary if they are on the same value chain or if the subsidiary is a partnered with the parent in product development. Many third-party US firms will also need to report their emissions data to the affected EU-regulated firm because of their business connections.

In essence, the EU’s CSRD uses US-based subsidiaries as vehicles to punish larger US-based firms that would otherwise not be influenced by the EU’s reporting requirements. This complex regulation-by-association imposed by distant EU officials on US parent firms will make transatlantic investing far less attractive in the future.

The EU also goes beyond the SEC’s rule in that it requires firms to expend additional resources to hire certified accountants to produce assurance reports. The SEC’s final rule reduced some of its initial assurance requirements to extend a “phase-in period” for large and accelerated filers, while limiting the assurance requirements for only accelerated filers.

The EU’s reporting requirements officially began in January 2024, with a mandate that EU member countries incorporated CSRD’s regulatory requirements by a July 2024 deadline. While the SEC’s rule introduces a novel set of climate disclosures for companies to report, the EU bases its rule on strengthening preexisting ESG mandates like NFRD with aggressive new reporting standards like ESRS. As such, the EU’s rule uses earlier laws as a template for its legally binding and enforceable CSRD.

The ESRS framework was formally adopted by the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) in 2023. EFRAG was formed as a private association in 2001 by a broad coalition of European interest groups representing the accounting profession. While EFRAG is private on paper, it operates at the behest of the European Commission. Since its founding, EFRAG’s primary role has been to conscript publicly listed banks, insurance companies, and bank federations to comply with a uniform set of standards that align with the EU’s regulatory interests. This has earned it a distinction as the “European voice of financial reporting.”

Europe’s largest financial institutions are required by EU law to adopt EFRAG standards in consolidated accounts. EFRAG ensures that these institutions report environmental impact and climate risk disclosures in a manner that is aligned with ESRS. EFRAG cracks down on perceived misconduct across Europe and serves a purpose similar to the SEC’s recently disbanded ESG Enforcement Task Force.

EFRAG’s regional influence also resembles how the TCFD has spurred US domestic reporting requirements in the SEC’s climate disclosure rule. EFRAG extends its influence far beyond European soil to affect over 100 jurisdictions globally.

The issue with EFRAG’s broad influence is that it imposes unreasonable expectations on European companies. This translates to forcing firms to merge preexisting ISSB standards with the newly updated ESRS standards.

In attempting to merge these reporting standards, firms will need to find a way to accommodate the EU’s aggressive sustainability requirements through ESRS with the more passive baseline elements of ISSB. The greatest difficulty will be to retrofit ESRS’s experimental notion of “double materiality” onto ISSB, ensuring that climate reporting advances the EU’s vision of corporate sustainability.

In essence, firms must diminish their traditional focus on disclosing purely financial risk and opportunities, while elevating the disclosure of climate-related concerns and how these introduce opportunities for sustainable investment. Companies cannot overlook what is material simply to appease the demands of different regulators by providing non-material data.

The redundancy of imposing mandatory climate reporting is that companies already know what is material for their investors. Most firms act within the best interests of investors to provide such pecuniary information through traditional financial reports.

And when this hodgepodge of ESG reporting standards proves to be untenable for many firms, EFRAG and the SEC’s taskforces will stand ready to make examples of noncompliance with their enforcement functions.

The trap of double materiality

Materiality is a fundamental concept in American securities law. The SEC, at its creation, was empowered by Congress to require the disclosure of certain information from publicly traded companies, but those powers are not unbounded.

The agency’s disclosure authority is limited to topics that Congress specified in statute. To keep investors informed, Congress requires public companies to report changes in their registered securities, managerial responsibilities, business development, and financial performance on a quarterly and annual basis.

These areas of disclosure have been understood over time to be “material” to the investment decisions of the average investor. While there is no statutory definition of materiality, there has been a consensus among regulators and firms alike regarding what materiality entails for the average investor. This broad consensus was reaffirmed by the US Supreme Court in 1976. Likewise, the SEC has recognized several highly similar definitions of materiality that each align with the Supreme Court’s ruling.

Despite this legal precedent, climate activists worldwide and EU regulators have advanced a different theory of disclosure that has been called double materiality. Double materiality has been so named because it considers: (1) what is financially important to the investor and (2) what regulators deem to be societally or environmentally important.

Double materiality allows regulators to justify mandating ESG disclosures. Because the EU maintains that broader stakeholder interests are equal to the financial interests of investors, EU companies must report a much broader range of external factors that influence business decisions.

The closest US equivalent to double materiality are unofficial frameworks like the “triple bottom line” (TBL’s three pillars are “social, environmental, and economic”) and the “four P’s” of “purpose, people, planet, profit.” This extended-stakeholder view is, at least rhetorically, in line with major policy announcements in recent years like the 2019 declaration by the Business Roundtable redefining the purpose of a corporation as a social engine for change.

The EU’s CSRD incorporates double materiality by requiring companies to capture and report financial and non-financial metrics pertaining to the firm’s climate change risks. They must also prepare an official climate impact portion of their report to the EU, which represents a form of “integrated reporting” used by various institutional investors like the Dutch Pension Fund and large corporations like Shell. Integrated reporting artificially combines a firm’s financial performance expectations with social or environmental considerations.

The SEC’s climate rule is less forthright than the EU’s rule. It seeks to redefine US materiality by incorporating an implied form of double materiality that hasn’t been recognized by Congress or any court of law. SEC regulators now assume that concerns over climate change automatically warrant material consideration. Accommodating that assumption via government mandate subverts the legally recognized view of materiality.

While the SEC stops short of outlining what climate risks may or may not be materially relevant, public firms will be at great risk if they fail to report any climate-related issues. In other words, public companies will not receive a free pass from the SEC, their own activist shareholders, or environmental activist groups for simply declining to report any climate change risks. Many firms will likely play along with the SEC’s implied recognition of double materiality to avoid noncompliance actions.

The EU’s materiality disclosure requirements go further than the SEC’s rule. This can be seen in how the EU’s CSRD requires companies to provide an assurance report on disclosures, while the SEC currently leaves this as merely an option. The SEC’s rule provides a “materiality qualifier” for companies to have some wiggle room in deciding what issues are materially relevant to disclose. The EU’s rule affords no such discretion.

As a result, EU-regulated firms, including US subsidiaries, will need to hire more professionals to prepare separate assurance reports that affirm a firm’s reported climate impact. Because of this strict assurance requirement, firms will have little to no room for error when seeking to convince the EU of how material climate risks factor into their financial performance.

Additionally, the EU’s CSRD requires companies to adequately “report both on their impacts on people and the environment, and on how social and environmental issues create financial risks and opportunities for the company.” This will contribute to a transatlantic disparity between what climate risks are deemed material and how this impacts financial decision-making.

This disparity in climate reporting underscores an important argument against multiple climate disclosure laws. Despite the rules’ unified goal of standardizing climate reporting, the end result will likely be the incomparability and inconsistency of climate disclosures that will vary globally and even domestically.

At the heart of this confusion is that the EU’s strict enforcement of double materiality will misalign with the SEC’s climate rule, which only implies, rather than dictates, double materiality. Setting the SEC’s climate activism aside, the existing Supreme Court precedent and the Code of Federal Regulations does not afford room for a double-materiality standard.

California’s renegade push for disclosure

While California’s rule is more narrowly tailored than the SEC’s rule in terms of demanding fewer environmental categories for disclosure, its regulatory reach is more invasive. It will punish both public and private firms for their carbon footprints.

California rule is unique for becoming the first state to enact an ESG reporting law. The Golden State is widely regarded as a trend-setter among American states for pushing the envelope of environmental policy. Being the first state to officially compel climate disclosures is just the most recent example. With one of the largest economies in the world, California’s mandatory rule will directly affect roughly 10,000 businesses.

California’s requirement that companies estimate their carbon footprints is consistent with the state’s other aggressive environmental policies, including the scheduled ban on the sale of all new internal combustion engine vehicles starting in 2035. This mandate is part of a larger ongoing effort to achieve a green-energy transition to a future net-zero state economy.

In the Spring of 2023, California’s legislature passed three bills containing three separate climate reporting provisions that comprise California’s landmark climate rule. One measure, the Climate Corporate Data Accountability Act, requires all companies to provide scope reporting for their direct, indirect, and value-chain emissions. Secondly, the Voluntary Carbon Market Disclosure requires companies to disclose how they engage in decarbonization efforts through the voluntary sale and marketing of carbon offsets and whether their carbon reduction goals are being met.

Finally, California’s Climate-Related Financial Risk Act requires a biannual disclosure that incorporates recommendations issued by the recently merged TCFD, requiring firms to account for how climate-related financial risks adversely impact their business.

Both public and private firms with operations in the state must now proceed with extreme caution when engaging in carbon-emitting activities, which will be captured and reported under the Accountability Act. This provision will negatively affect 5,300 companies that generate at least $1 billion in annual revenue.

The Accountability Act will allow climate activists to use the data disclosed to attack firms, even when their conduct is law-abiding and in the interest of shareholders. This will likely take the form of coordinated legal and public relations attacks against firms deemed to be high GHG emitters. Many California activists already brand big business as a threat to the environment. The text of the Act reveals that “environmental justice interests” will be consulted to guide the implementation of the disclosure rule, rather than the affected firms.

Climate activists in and out of government will likely weaponize the Risk Act as well. This rule, combined with the Scope 3 provision of the Accountability Act, was designed to compel decarbonization across private businesses, which will ensnare a number of small firms. Large firms generating $500 million annually will need to submit biannual reporting of their physical and transition climate risks and what steps they are taking to address them.

As a result of the Risk Act, around 10,000 regulated companies will lose their managerial discretion over these risks. California’s government has spoken for these companies by deeming that any potential climate risk is mandatory for reporting and resolving.

Activists and officials can use California’s proposed disclosure laws to accuse firms of engaging in deceptive practices and contributing to climate-related catastrophes. We’ve already seen California state officials use climate accusations to go to war with major energy companies, like Exxon Mobil, even in the absence of official climate reporting laws. If California’s climate disclosure rules are fully implemented, they will drive activist litigation to new levels by providing a new exploitable legal framework for such complaints.

The heightened legal battles to come from the Risk Act are emblematic of an ongoing struggle between climate activists and energy companies in California. Ryan Meyers, vice president of the American Petroleum Institute, stated in response to California’s 2023 lawsuit that sought to force energy firms to pay for severe weather recovery efforts, “This ongoing, coordinated campaign to wage meritless, politicized lawsuits against a foundational American industry and its workers is nothing more than a distraction from important national conversations and an enormous waste of California taxpayer resources.”

Activists can also use California’s Risk Act as a cudgel to punish firms in court for allegedly failing to go far enough to mitigate the risks associated with climate change. Like the SEC’s rule, California has followed many of the TCFD recommendations, including the imposition of the GHG Protocol’s scope 1-3 reporting system.

On climate policy, California’s Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom even boasted that “we move the needle for the country, and, as consequence, for the globe. And that is profound.”

The Carbon Market disclosure also undermines the corporate discretion of California businesses to engage in a truly voluntary exchange of carbon credits. Regulated firms must now outline how they are using carbon offsetting to achieve net zero. This expectation could be a major problem given both the declining market demand for carbon offsets nationwide and the real difficulty of firms coming close to meeting their net-zero benchmarks. Violating the terms of California’s carbon credits disclosure guidelines will result in businesses paying a civil monetary penalty of up to $2,500 per day. California is setting an example for states like Illinois, Minnesota, and New York that are working to adopt similar climate rules. These states seek to adopt their own climate accountability acts, modeled after California’s legislation in that they target both public and private businesses with Scope 1-3 GHG disclosure requirements. Yet, Illinois has been struggling all year to even pass its costly climate proposal out of legislative committee.

Nor are things sailing smoothly even in California. Gov. Newsom has delayed his state’s climate reporting requirements by two years, perceiving the original scope reporting timeline to be unreasonable for businesses. As a result, California businesses won’t need to report their Scope 1 and 2 numbers until 2028 (rather than 2026) and Scope 3 by 2029. So, while California was the first state to adopt mandatory climate reporting laws, the EU may outpace it to be the first regulatory body that actually imposes its climate mandate on US businesses.

California’s law retains more stringent reporting requirements than the SEC and EU with its mandatory carbon offsetting and TCFD components. This will negatively affect many of the estimated 1.7 million private firms housed in the state.

Triple disclosure = cost multiplier?

Each of the three climate disclosure mandates carries its own hefty set of compliance costs and expectations. US firms subject to all three will need to fashion climate disclosures that satisfy each of the reporting demands. The climate disclosure submitted to the SEC cannot simply be used to satisfy the EU’s or California’s disclosures, especially given that California and the EU impose formal Scope 3 reporting requirements, while the SEC’s does not.

To demonstrate the severity of the triple-disclosure burden, imagine an SEC-registered US firm that does business in California and European markets. The firm owns businesses across multiple EU-member states and California.

Rather than submitting a one-sized fits all climate disclosure that satisfies all three regulators, the firm must conduct a complicated accounting exercise to prepare separate, detailed reports that cater to the regulatory landscapes in which they do business.

For example, the firm must place greater emphasis on the unique physical risks associated with California’s wildfires, droughts, and alleged sea-level rises, depending on their firm’s business locations. These physical risks will differ vastly from the firm’s locations across Europe (captured by the CSRD) and in its firms located across US states beyond California for the SEC’s rule.

Additionally, the SEC’s GHG report will provide a much more limited outlook on the firm’s carbon footprint, focusing only on emissions from their direct (Scope 1) and purchased energy (Scope 2). By contrast, California and the EU’s scope mandate will dwarf the SEC’s version by flooding investors with even more confusing GHG data from their many private partners. Reporting firms will need to quantify and account for their decentralized emissions across the value chain (Scope 3).

Each of the three rules varies widely on the categories of disclosure and the standards on which to base such information. California’s Risk Act requires firms to align their reporting with the TCFD’s recommendations, while the SEC’s rule does not require the adoption of any third-party standard. The EU requires all firms (including EU-based US subsidiaries) to strictly adopt ESRS reporting standards. Firms facing a triple-disclosure burden will thus be unable to report their climate risks and opportunities in a consolidated manner.

Private companies that partner with regulated US firms doing business in Europe and California may need to submit Scope 3 data for both rules. California’s rules extend to both public and private companies, the EU’s rule similarly captures all public and many large private firms across EU member states, while the SEC’s rule applies, theoretically, to only publicly registered firms.

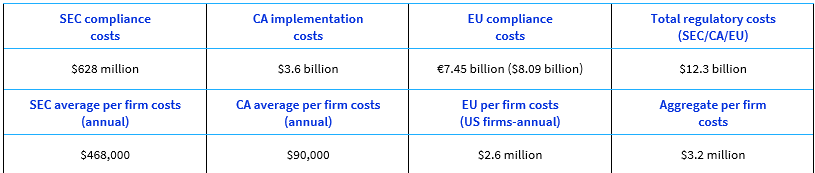

Table 1

In addition to varying expectations, each rule carries its own set of compliance costs. Regulators do, at times, attempt to minimize the cost-burden imposed by their own rules. However, regulators seldom consider the overlapping compliance burdens for multi-jurisdictional climate mandates. Such burdens were clearly overlooked by all three regulatory bodies imposing their own specialized climate mandates.

Below is a table estimating the annual compliance costs for each rule and the enhanced costs for businesses regulated under all three mandates.

The price tag of California’s climate rules is based on its initial implementation costs. The ongoing annual compliance costs have yet to be reported and will likely impose a much higher financial burden for firms. Such compliance costs will likely take the form of California Air Resources Board (CARB) assessing annual fees against regulated firms for their environmental impact.

To fund the creation, dissemination and collection of climate disclosures, California’s government has diverted $3.6 billion from the state’s general fund to the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF). This will translate to roughly $90,000 cost per firm per year, across the estimated 10,000 firms affected.

Additionally, California’s revised 2024-2025 budget shows that the state decided to eliminate $22 million in direct oil and gas subsidies, divesting the proceeds to fund its climate disclosure programs (via the GGRF). GGRF is bolstered by the state cap-and-trade program, which will be used to help finance the climate rule’s implementation.

In other words, California is taxing companies for their carbon emissions through cap-and-trade and using the gathered revenue to impose an even greater corporate burden in the form of its climate reporting laws.

This is California’s way of paying for the rule using higher corporate taxes, which Gov. Newsom has sought to increase by $18 billion over the next four years. This would occur over the same period that companies will pay more (in fees) for their climate reporting. Much of this increase in corporate taxation is going to cover the annual expense for implementing the climate rules, which requires CARB to “identify covered entities, write regulations, develop and maintain a verification program, and conduct other tasks.”

The EU’s $8.1 billion CSRD appears to be the first European disclosure mandate that thousands of US companies will be saddled with. Table 1 captures the per-firm costs for the affected 3,000 firms based in the US, estimated to be $2.6 million for each firm.

The CSRD’s cost covers the combined administrative and assurance costs (direct and indirect) that regulated firms will need to pay, which is expected to be somewhat less severe for non-EU based US firms. Still, the CSRD fails to provide any form of regulatory waiver or exception for US owned subsidiaries and parent firms.

Regarding the SEC’s climate rule, the $468,000 figure in Table 1 represents the average per-firm costs for public companies beginning in the second year of reporting. The low end of these estimated annual compliance costs is around $197,000, while the high-end estimate is $739,000. This figure is separate from the notably higher first-year costs that firms will pay, which averages $931,000 between the small reporting companies at one end and over $1 million for large accelerated filers at the other end.

The SEC’s climate rule ostensibly marks a 10 percent increase in total annual compliance costs for businesses ($628 million), rising from $3.8 to $4.2 billion. The actual cost increase is likely much greater than stated, as the SEC failed to conduct a proper cost-benefit analysis. There are many unaccounted-for indirect costs and long-term economic consequences posed by the rule that the base $628 million price tag fails to capture.

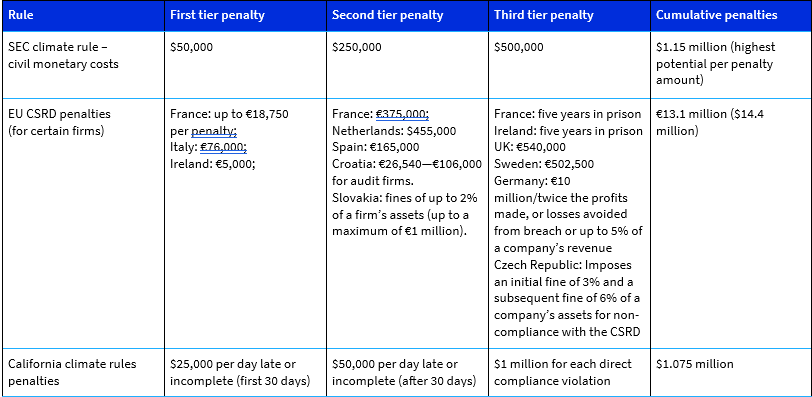

In addition to the three rules’ combined compliance costs of $8.7 billion, it is important to get a sense of how much US firms may need to pay for violating one or more of these provisions. The following table examines the overlapping costs for compliance violations that US entities may be forced to bear.

Among the three regulatory bodies, California’s CARB is the only entity not authorized to financially penalize businesses for violating its climate rules. This is because CARB has yet to adopt official regulations for firms, which will need to be published by January 1, 2025, for the Climate Corporate Data Accountability Act to officially become enforceable. Despite this, California rushed to impose its climate rule and specified a set of penalties absent any clear regulatory guidelines or means to enforce its disclosure mandate.

According to table 2, California’s climate rule imposes the second highest potential cost burden per firm at up to $1.075 million per firm. There is a significant gap between California’s tier 2 and tier 3 compliance costs, as tier 3 shoots up by 95 percent for a single rule violation. Many firms will likely find this increase to be unreasonably severe.

Standing even above California’s penalty regime is the EU’s CSRD. The EU imposes the greatest combined cost burden of €13.1 billion among the eleven European countries that stand ready to punish firms for perceived disclosure violations. I organize tiers for the EU member state penalties based on severity. For tier 1, the financial penalty ranges in the €10,000s—€300,000s, tier 2 ranges in the €500,000s, tier 3 imposes prison time in addition to hefty financial consequences in the millions.

Each of the listed amounts in Table 2 represents the median values within a penalty range imposed by each EU member state. Germany is poised to impose the most severe monetary punishment by far, standing at a potential €10 million per firm. As an alternative, German officials may force the noncompliant firm to pay twice as much for the profits made or losses avoided from the stated breach to the CSRD.

Only a third of all EU member states have formally adopted the CSRD within the July 6, 2024, deadline. Among these nine countries, only three of them—France, Ireland, and Slovakia—have revealed their financial penalties for corporate noncompliance. If the remaining 18 EU nations continue to delay or refuse to adopt the CSRD into law, they will ironically face hefty EU penalties of their own for unwarranted delay.

The SEC’s climate disclosure rule comes in third for cost of compliance violations. The SEC does not list specific monetary penalties in the body of the climate disclosure rule. However, the SEC frequently charges market actors for disclosure related violations of various securities laws.

The listed penalties in table 2 represent the average ceiling for tiered civil monetary penalties that the SEC pursues against registered companies. These amounts can increase based on the nature and severity of the violation and represent the total amount that a noncompliant firm can be charged with. The $1.15 million figure represents the potential peak of a per-violation monetary penalty that the SEC can pursue (adjusted for inflation). SEC officials possess enormous discretion when calculating penalties that may exceed the listed tiered amounts above.

Material omissions to investors or violations of the SEC’s climate rule will likely fall within these penalty ranges. In certain instances, however, the SEC has been prone to impose far more severe monetary penalties that fall beyond these specified ranges, running into billions of dollars per year.

US companies that are penalized under all three climate rules and each compounding penalty will suffer substantially, facing upwards of $16.9 billion in punitive costs. This estimate is likely far lower than the actual combined penalties, as it doesn’t account for the other EU member states that have yet to disclose their enforcement standards.

Firms that fail to course-correct may face multiple penalties that will compound over time, based on the SEC and California’s specified tier system. For the EU, table 2 places member states into unofficial tiers based on how costly certain countries compliance violations run. The most draconian and costly violations will be imposed on US firms located in Germany, Ireland, and France.

Legal concerns over jurisdictions

These three climate disclosure rules will have a disparate impact on US firms affected by multiple jurisdictions. This will generate a multiplier effect of administrative burdens: heightened compliance costs, substantial time burden to prepare two or three detailed disclosures, psychological costs for confused investors, and a daunting learning curve for firms unfamiliar with or unable to prepare fully compliant climate disclosures. This may represent what my colleague Wayne Crews calls a “tip of the costberg” for many firms attempting to satisfy compounding regulatory costs for its environmental activities across multiple jurisdictions.

US firms with locations in EU states or that list securities on an EU-regulated exchange will be subjected to a costly foreign mandate that has no basis in or connection with domestic securities laws.

Given that none of the three climate rules provide safe harbors to overlapping disclosure mandates, many US firms will be subjected to dual or triple disclosure burdens. When accounting for California’s controversial climate rules, the result will impose a web of ESG compliance requirements for registrant firms. Not only is there no official interoperability—using one rule’s requirements to satisfy the others—between the three mandates, but there are also no exemptions for firms hit multiple times by scope reporting and other violations.

Additionally, it will be confusing for the US firms to adapt their disclosures to satisfy both the SEC and EU. Some environmental matters may be deemed materially relevant for reporting to the EU via double materiality, while other risks may not be relevant to the SEC’s rule under single materiality.

Each disclosure mandate carries varying compliance requirements, differing forms of materiality, and conflicting reporting standards for the EU and… California, and no universally… accepted standard for the SEC. This confusion will practically invite crackdowns by regulators in the form of what has been called “regulation by enforcement,” in addition to incentivizing activist investors to launch lawsuits against firms over the quality of their ESG disclosure.

US firms, for instance, will suffer greater exposure in court for the unfeasibility of their carbon offsetting programs. While all three climate rules require firms to be forthcoming in detailing their carbon offsetting programs (i.e., exchange of carbon credits), EU-based firms that fail to show how offsetting meets the law’s prescribed GHG reduction targets are at greater risk of noncompliance. Firms will be required to justify their use of carbon credits as a concrete means for justifying carbon emissions, regardless of how unpopular or unfeasible the carbon market has proven to be.

Conclusion

As the EU prepares to enforce its CSRD mandate, the SEC and California each grapple with a major set of legal challenges and setbacks. If any of these three regimes are allowed to go into effect, many US firms will be ensnared by climate disclosure requirements. As a European directive, the EU’s CSRD threatens to undermine the US constitutional and state corporate law protections of US companies by imposing a foreign set of ESRS standards that have not been recognized in domestic securities laws.

Likewise, the SEC’s rule operates outside of the scope of federal law by adopting a novel, unofficial form of climate change materiality. US firms must grapple with the incoming regulations associated with dual or even triple climate disclosures if each of these mandates survive legal challenge. While the SEC and California’s rules are already under fire from a range of lawsuits, the EU’s rule faces greater insulation from litigation. This is because CSRD is protected by various international laws like the European Green Deal and standards like the ESRS. This makes their climate rule more interwoven into the corporate fabric of the continent and enforceable on European firms. By contrast, the SEC and California’s rules are much more vulnerable to being toppled in a domestic court.

Despite the EU’s more durable structure, the CSRD faces problematic implementation delays just like the SEC and California. Both California and the SEC have delayed the effectiveness of their mandates to combat major legal challenges and funding issues (in California’s case). By contrast, two-thirds of EU member states have failed to implement the CSRD into law by the July 2024 deadline.

The EU’s stringent climate reporting standards will likely depress share prices of affected firms, decreasing their short-term value in the capital markets. Each of the three rules (SEC/EU/CA) stand to expose the largest GHG emitting firms to greater threat of litigation from climate activist groups. Similarly, large firms with multiple satellite locations throughout Europe run the risk of triggering CSRD compliance violations across multiple countries, each containing their own degree of punitive standards.

Compliance costs will only compound for many unfortunate firms that violate multiple climate regulations or one regulation multiple times. This paints a bleak picture for US firms (both public and private) seeking to expand into European markets. Worse, they can get stung by regulation simply for maintaining a lucrative subsidiary in EU capital markets.

If nothing is done at the US federal level to prevent the implementation of government-mandated climate reporting, we may see more states emulate California’s climate reporting rules and other rogue agencies adopt the SEC’s desired approach to climate regulation. And, if the US government doesn’t push back against the EU’s unwarranted interference in domestic commerce, other foreign bodies could pile on similar regulation in the future.

Many US firms are already bracing for some form of mandatory climate disclosure. Absent serious pushback, the business environment may get much worse than they expect. Mandatory reporting requirements from several regulators are arbitrary and overly complicated, burdening companies with severe administrative costs that outweigh their potential benefits. Ultimately, businesses, not regulators, should determine what climate risks are worth disclosing to their investors.