Goodbye to the roaring twenties of regulation? A cost roundup

Photo Credit: Getty

The final Report to Congress on the Benefits and Costs of Federal Regulations from the Biden administration appeared January 15. Here at the middle of this second decade of the 21st Century, the transition between Biden and Trump offers an opportunity to take stock as Trump tees up a ten-for-one operating mandate for rulemaking.

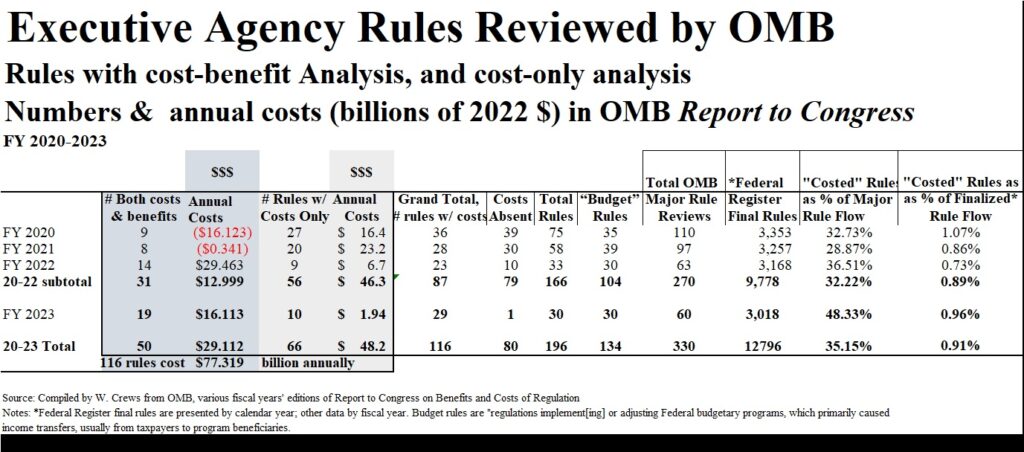

For fiscal year 2023 (which ended September 30 of that year) the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) quantified the costs of 19 major rules sporting both benefit and cost assessments at $16.1 billion annually. Another 10 rules lacking monetized benefits but costing an additional $1.92 billion annually was also disclosed, as seen here.

Fiscal years 2020 through 2022 appeared in a composite, catch-up edition of the Report to Congress back in 2023. As may also be seen in the table above, 31 rules with both benefits and cost quantified boast $13 billion in annual costs, while 56 more with solely costs assessed add another $46 billion annually.

We’re in fiscal year 2025 now, however, and a draft 2024 report never appeared despite the issuance of rules last year with total cumulative costs (as opposed to annualized costs that concern us here) exceeding $1 trillion, much of which was accounted for by just a few rules. Without an official report, those costs are not included here in our current roundup.

What we can say now is that, by official estimates, 116 rules issued so far in the second decade of the 21st Century add $77 billion in annual regulatory costs. Inventories of those rules appear in Appendices A and B of the 2024 Ten Thousand Commandments (through 2022, that is; the 2023 component will be included in the forthcoming 2025 edition). Among these rules are familiar examples like vehicle fuel efficiency, building energy conservation, industrial admissions standards, COVID-19 paid leave, as well as certain savings from the first Trump term that appear as negative values in the table above.

While eye-opening, these cost figures barely scratch the surface of the federal regulatory burden. The first 20 years of the century found OMB noting $151 billion in annual costs added from rules with both costs and benefits quantified (averaging around $7 billion annually). In addition, there were dozens of cost-only rule disclosures with high-end estimates that totaled $54 billion.

So, where the first two decades of the century brought some $205 billion in annualized costs, the first four years of this decade alone have added the aforementioned $77 billion. That’s a pace worthy of the roaring twenties moniker. The recent election of Trump presumably interrupts this surge—assuming Trump’s own “swamp things” like trade, antitrust and artificial intelligence interventions don’t flip the script.

Despite these costs, OMB routinely labels federal regulations as net beneficial despite acknowledging limitations of its selective assessments. The reality is that there has been no comprehensive assessment of aggregate regulatory costs in two decades, despite legal requirements for an annual reckoning from the disregarded Regulatory Right-to-Know Act.

Even with the sporadic annual reckonings we get, the percentage of rules reviewed with cost analysis remains low, as the table also shows. For example, the 29 of 60 acknowledged major rules reviewed in FY 2023 with cost analysis represents 48 percent of that major population—but a mere 1 percent of that calendar year’s total flow of 3,018 rules published in the Federal Register.

The Trump administration no doubt recognizes that the gaps in OMB’s cost reporting are substantial. Independent agencies such as the Federal Communications Commission and financial regulators are not reviewed. Antitrust actions, public-private partnerships, and federal controls over critical industries remain unaccounted for. Additionally, the economic consequences of guidance documents, memoranda, and other informal directives regulatory dark matter are largely ignored.

Further complicating the picture, cost-benefit analysis fails to fully consider opportunity costs—what might have been achieved if regulatory “budgets” were allocated differently not just withing an agency but across the federal enterprise. Instead, agencies operate in silos, each justifying their own regulations with inadequate regard for broader effects. This approach is particularly damaging now given that numerous complex infrastructure sectors segregated by regulators need to work together instead.

Many will be watching. If Trump’s ten-for-one policies are successfully implemented, the fiscal year 2025 Report to Congress will likely tell a very different tale that that of the Biden era.

For more see: