Favorable selection in Medicare Advantage can’t be managed from the top

Photo Credit: Getty

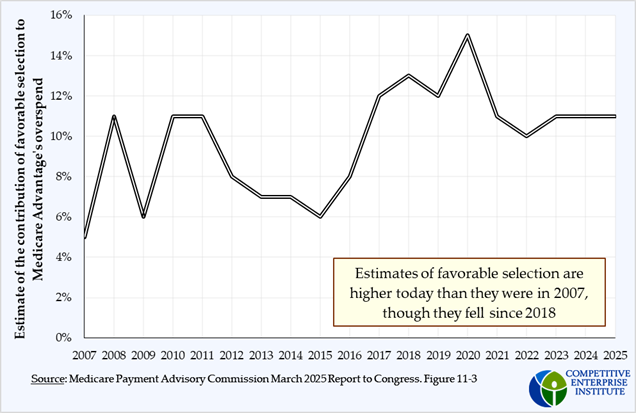

A previous post covered how the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) attempts to mitigate upcoding have been unsuccessful. Another often-decried activity in Medicare Advantage is known as favorable selection. As with coding intensity, the attempts to decrease its use demonstrate the limitations of using administrative analysts to engineer solutions to complex economic problems.

What is favorable selection?

As discussed in Part I, Medicare Advantage (MA) plans are paid a fixed amount per enrollee. While aggressive coding intensity can bump enrollees into a higher risk group and draw larger payments for the plans, the plans also have another tactic they can use to boost their profits. Because everyone in a certain risk group will earn the plan the same payment, plans are financially better off if they can enroll the lowest-cost person within any risk group.

As an illustration, imagine Medicare pays the same amount to plans for every person who enrolls in Medicare Advantage. Whether an enrollee is a 65 year-old pickleball champ or a 90 year-old requiring dialysis, the plans will receive the same dollar amount to pay for the member’s care. If the payment for both of those potential enrollees is the same, the MA plan would prefer to enroll the younger, healthier one, because the cost of providing them care will be lower.

The plan will then try to attract this person from traditional Medicare by doing things like offering pickleball equipment as part of the plan benefits. Health economists and policymakers refer to this inclination as favorable selection and have been trying to counter it for decades. As a matter of fact, this is a primary purpose of the risk groups.

How risk groups are supposed to counteract favorable selection

The idea behind risk groups is that grouping together people with similar costs will reduce the incentive for plans to engage in favorable selection. Now, all the pickleball players will be in one risk group, and all these people earn the plans the same dollar amount which is based on the average costs within the group. Similarly, all the 90 year-olds will be in their own group and the plans will receive a higher amount for these enrollees.

Using risk groups reduces favorable selection in two ways. First, it reduces the incentive for the plan to target the lower-cost beneficiaries because their payment will also be lower. Second, to engage in favorable selection, now the plan also must determine who is lower cost and devise methods to attract the less costly enrollees within each risk group, which would be more difficult. For example, if plans were offering free gym memberships to attract more active members, that wouldn’t work as well when healthier seniors are grouped together.

Real world failures of the risk-group approach

The risk adjustment process has been evolving since the inception of Medicare Advantage. Before 2000, the model used only a handful of demographic variables—age, sex, geography. In 2000, CMS began to integrate inpatient diagnoses into the formula, and by 2008, the current structure which also includes outpatient procedures was in place. Since then, CMS has been tweaking its risk adjustment model continuously to try to keep up with the plans’ own adaptations.

One study even concluded that risk adjustment enabled more favorable selection, saying, “We find no evidence that overpayments were on net reduced.”

Since the institution of Medicare Advantage, the federal government has been engaged in an arms race with private plans, developing new and more complicated approaches while also expanding the scale of its efforts. Despite these changes, the problems they’re trying to solve seem to be getting worse. It’s a losing battle because bureaucracies populated by technocrats are insignificant next to the power of incentives.

A better way

To truly solve these issues, the system should be oriented more around competition. Under a competitive market, the plans would bid each other down to offset any abuses. For instance, if a plan is adept at attracting relatively healthy beneficiaries, it has more space to lower its bid to attract them from other plans, which will cancel out whatever benefit they might’ve enjoyed. Other plans may follow suit, and the outcome may be one with substantial favorable selection and intensive coding, but because the plans are paid according to their bids, the costs are still held low.

This kind of competition should prevail regardless of the cost of care. While experience suggests that insurance companies prefer to serve low-cost beneficiaries, in a bid-based system, the bids would presumably be higher for high-cost beneficiaries, but still lower than the traditional Medicare costs. Perhaps plans would segregate enrollees according to cost but that is not necessarily the case, as this doesn’t happen in Marketplace plans. These private plans use a different mechanism to prevent favorable selection.

If there is a persistent focus on low-cost beneficiaries, or a scarcity of competition in any segment of the population, then traditional Medicare will still serve as a failsafe, so seniors could not be made worse off than today.

Designing a system that engenders competition and gives private agents the incentives to generate the desired outcomes is generally more effective and more efficient than fighting against a poorly designed one.