CEI comments on NHTSA’s proposed SAFE III Rule to prevent automakers from being forced to produce and sell electric vehicles.

Dear Mr. Bayer,

On behalf of the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI), thank you for the opportunity to submit comments on the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s (NHTSA’s) proposed SAFE III Rule.

CEI strongly supports NHTSA’s proposal. SAFE III would realign the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) program with legislative intent, reduce CAFE compliance burdens, enhance US auto industry competitiveness, promote consumer choice, and avert an estimated $900 increase in average new car prices.

SAFE III would repeal and replace the Biden administration NHTSA’s CAFE standards. Under the Biden program, CAFE standards for passenger cars increase in stringency by 8 percent per year for model years (MYs) 2024–2025, 10 percent per year for MY 2026, and 2 percent per year for MYs 2027–2031.

In sharp contrast, the proposed SAFE III CAFE standards increase by 0.5 percent per year for MYs 2022-2026, 0.35 percent per year for MY 2027, and 0.25 percent per year for MYs 2028-2031.

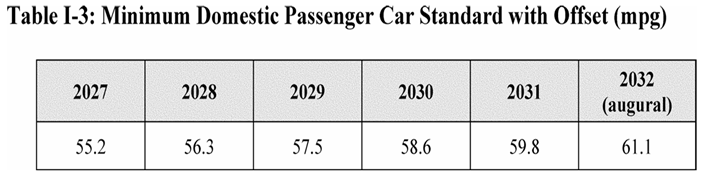

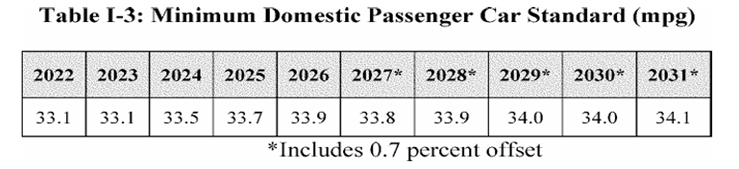

The resulting reduction in regulatory stringency is substantial. Here are the minimum domestic passenger car fleet average standards in NHTSA’s June 2024 CAFE rule:

Here are the standards in the proposed SAFE III Rule:

NHTSA seeks comment on “all aspects” of the SAFE III proposal. CEI’s comments aim to strengthen the case for SAFE III’s restoration of the rule of law and economic rationality in federal motor vehicle regulation. SAFE III will not only repeal regulatory excesses of the previous administration. It will also re-center the CAFE program on long-obfuscated statutory restrictions, thwarting future acts of regulatory overreach.

The comments are organized as follows.

- Section I reviews California and the Biden administration Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) coercive vehicle electrification programs.

- Section II reviews the Biden administration NHTSA’s pivotal and auxiliary roles in advancing coercive vehicle electrification.

- Section III reviews the unlawfulness of coercive vehicle electrification under the major questions doctrine and § 32919(a) of the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA).

- Section IV reviews the statutory imperative for SAFE III’s CAFE reset—EPCA § 32902(h), which does not allow NHTSA, when determining fuel economy standards, to consider either the fuel economy of dedicated and dual-fueled automobiles or the availability of regulatory credits.

- Section V concludes the comments.

I. California and EPA: forced electrification via sales mandates and performance standards

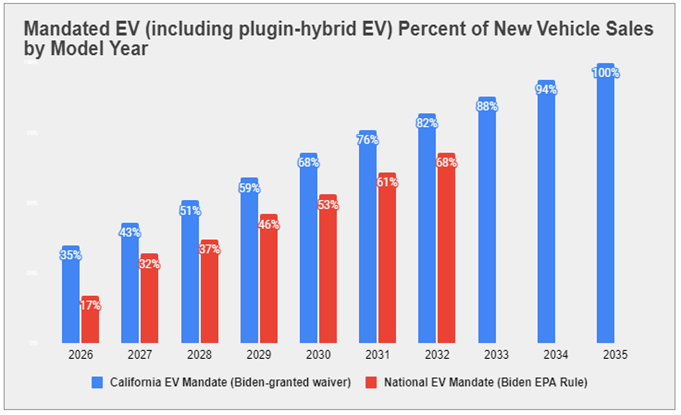

There are essentially two ways a regulatory agency can coerce automakers to shift production and sales from internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles that run solely or chiefly on liquid fuels such as gasoline and diesel fuel, to electric vehicles (EVs), which run solely or chiefly on batteries or fuel cells. In NHTSA’s regulatory classification, the main types of EVs are battery electric vehicles (BEVs), plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHEVs), and fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs). The most direct way an agency can force a shift from liquid fuels to batteries is through express mandates that require specific annual percentages of new car sales to be EVs. California’s zero emission vehicles (ZEV) program, which would effectively ban sales of new gas- and diesel-powered cars by 2035, is the best-known example.

Source: California Air Resources Board (CARB)

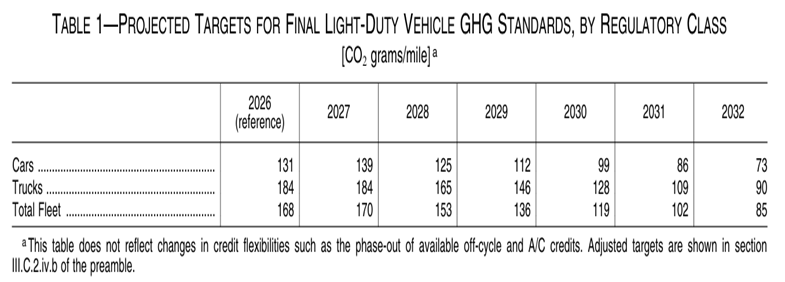

The other method of forcing vehicle electrification is to establish fleet-average performance standards, calibrated in miles per gallon (mpg) or grams of carbon dioxide per mile (g CO2/mi), that automakers cannot meet without averaging in the “fuel economy” or emissions profile of “dedicated” and “dual-fueled” automobiles (such as BEVs and PHEVs, respectively) that operate solely or chiefly on energy sources other than gasoline and diesel fuel. That was the EPA’s strategy during the Biden administration, beginning in its first year.

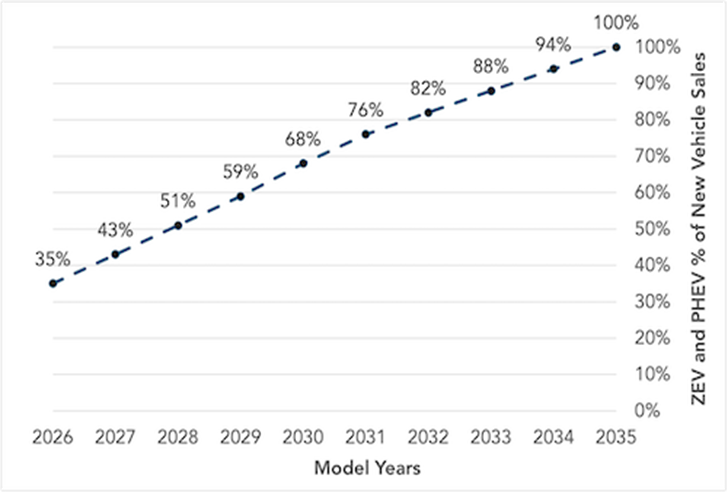

The EPA in December 2021 adopted tailpipe CO2 standards that effectively required automakers to boost EV sales. In the EPA’s words, its MY 2023-2026 tailpipe CO2 standards “will necessitate greater implementation and pace of technology penetration through MY 2026 using existing GHG [greenhouse gas] reduction technologies, including further deployment of BEV and PHEV technologies.” The EPA projected that BEVs and PHEVs would make up 17 percent of new car sales by MY 2026.

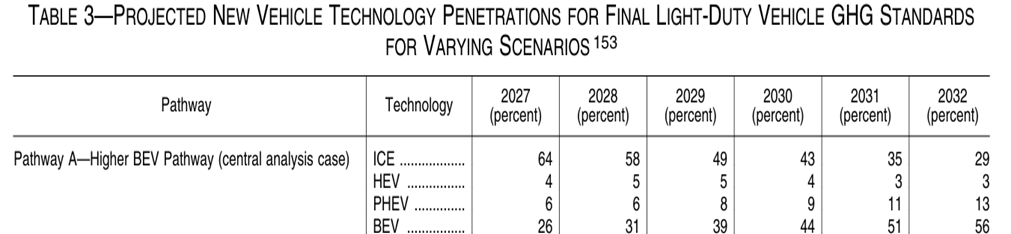

The EPA’s MYs 2027-2032 GHG emission standards were more aggressive. The EPA projected that by MY 2032, the market share of BEVs and PHEVs would increase to 69 percent, while that of ICE vehicles (including fuel-efficient hybrid vehicles) would decline to 31 percent.

The EPA denied that its tailpipe emission standards were sub rosa EV sales mandates. However, the functional similarity between the EPA and California programs is unmistakable. As one commentator put it, the EPA vehicle emissions program is a nationwide version of California’s gas-car ban with a two-year delay and the outyears hidden.

Source: Phil Kerpen, Unleash Prosperity (April 2024)

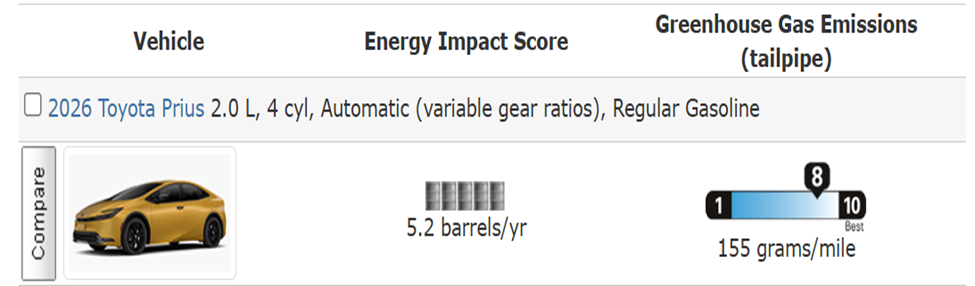

That the EPA standards implicitly mandate EV sales—and effectively squeeze ICE vehicles out of the market—becomes crystal clear when we compare those standards to the emissions profile of Toyota’s best-performing Prius hybrid. The EPA’s passenger car standard for MY 2032 is 73 g CO2/mi. The Prius emits 155 g CO2/mi.

Note that Toyota also manufactures hybrids and non-hybrids with significantly higher emission profiles, such as the Corolla Crown AWD hybrid, rated at 214 g CO2/mi, and the non-hybrid Corolla (1-mode TM), rated at 248 g CO2/mi.

Thus, even if Toyota wiped out its entire product line except for its best performing Prius, the fleet average (155 g CO2/mi) would be more than double the EPA’s MY 2032 standard (73 g CO2/mi). The EPA standards undeniably put pressure on legacy manufacturers to shift production and sales from ICE vehicles (including hybrids) to EVs.

To downplay the agency’s role in the “transition to a clean vehicles future” (after crowing about it in the rulemaking press release), the Biden EPA ascribed much of the projected 69 percent EV market share in MY 2032 to external factors, including EV tax credits and charging station grants provided by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), market demand for plug-in vehicles, and “California’s Advanced Clean Cars II program and its adoption by section 177 states.”

However, the EPA neglected to mention that it brought California’s ZEV program back from the regulatory boneyard in March 2022 by reinstating the Obama EPA’s January 2013 Clean Air Act preemption waiver for the state’s Advanced Clean Cars (ACC) program. That decision was widely expected after Election Day 2020, as was the EPA’s subsequent decision, in December 2024, to waive preemption for the state’s Advanced Clean Cars II (ACC II) program, with its 100 percent gas-car ban.

In short, the EPA was no mere surfer riding a wave generated by others. The EPA’s full-throttle partnership with California was a major force behind the “market trends” it cited as evidence for the cost-reasonableness and feasibility of its automobile GHG standards.

The good news, from a free-market perspective, is that, in June 2025, President Trump and Congress enacted a Congressional Review Act resolution of disapproval overturning the ACC II waiver.

II. NHTSA’s pivotal and auxiliary roles in advancing coerced electrification

As indicated above, the EPA’s March 2022 reinstatement of its January 2013 waiver for California’s ACC program and December 2024 waiver for the ACC II program empowered the state to resume and intensify its regulatory assault on vehicle affordability and choice. However, NHTSA’s December 2021 repeal of its portion of the Trump administration’s SAFE I Rule was the critical legal prerequisite for the EPA’s reinstatement of the ACC waiver and approval of the ACC II waiver.

SAFE I was a joint rulemaking by NHTSA and the EPA. NHTSA, for its part, reviewed California’s tailpipe CO2 emission standards and ZEV sales mandates under EPCA § 32919(a). That provision expressly prohibits states from adopting or enforcing laws or regulations “related to” fuel economy standards. SAFE I determined that policies regulating or prohibiting tailpipe CO2 emissions are “related to” fuel economy standards. Hence, EPCA preempts California’s tailpipe CO2 standards and ZEV mandates.

The logic of SAFE I’s preemption analysis is clear and compelling. An automobile’s CO2 emissions per mile are directly proportional to its fuel consumption per mile. Thus, if an agency regulates tailpipe CO2 emissions, it implicitly regulates fuel economy, and vice versa. Fuel economy and tailpipe CO2 emissions are “directly” related by fuel combustion chemistry and mathematical convertibility. They are “two sides (or, arguably, the same side) of the same coin.” Unsurprisingly, “there is a single pool of technologies for addressing these twin problems, i.e., those that reduce fuel consumption and thereby reduce CO2 emissions as well.”

ZEV mandates are “substantially” related to fuel economy standards. As ZEV mandates tighten, EV market share increases, eventually boosting fleet-average fuel economy as well. Conversely, when fuel economy standards exceed the capacity of combustion engine vehicles, compliance increasingly requires higher EV sales and/or lower ICE vehicle sales.

In its portion of SAFE I, the EPA, partly in affirmation of NHTSA’s preemption analysis, but also because vehicular CO2 emissions in California have no relevance to the state’s air quality challenges, withdrew the CAA preemption waiver it had granted in 2013 for the ACC program.

Preemption statutes derive their authority from Article VI of the Constitution, the Supremacy Clause. As the Supreme Court explained in Maryland v. Louisiana (1981), “It is basic to this constitutional command that all conflicting state provisions be without effect.” Consequently, any conflicting state policy is void ab initio—from the moment the policy is adopted or enacted, not when a court later declares it so.

That means the EPA could not authorize state policies preempted by EPCA by waiving preemption under a different statute. EPCA preemption itself is non-waivable and does not even allow states to adopt or enforce regulations identical to federal fuel economy standards.

In short, EPCA voided California’s tailpipe CO2 standards and ZEV mandates years before the Obama administration EPA agreed to review them under CAA § 209(b). EPCA turned those policies into legal phantoms—mere proposals without force or effect.

The Trump administration NHTSA incorporated SAFE I’s preemption analysis in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). With SAFE I on the books, the Biden administration could not reinstate the 2013 ACC waiver or grant the ACC II waiver. SAFE I repeal was therefore a day-one priority for the Biden White House.

Although the Biden administration NHTSA repealed SAFE I, it did not even try to refute its preemption argument. Indeed, NHTSA’s May 2021 repeal proposal did not quote or summarize SAFE I’s preemption analysis. Nor did the December 2021 final repeal rule, although excerpts from comments by CEI and other SAFE I supporters conveyed the gist. NHTSA agreed that EPCA § 32919(a) preempts state policies “related to” fuel economy standards. However, it declined to say which state policies might be related or “opine on the substance of EPCA preemption.”

In addition to its pivotal role of rescuing California’s “clean car” ambitions, the Biden administration NHTSA also had an auxiliary role, namely, provide a regulatory backstop in case future litigation or policy shifts upend the EPA/California vehicle electrification agenda. As NHTSHA’s proposed MYs 2027-2032 CAFE rule cautiously put it, “CAFE standards can also ensure continued improvements in energy conservation by requiring ongoing fuel economy improvements even if demand for more fuel economy flags unexpectedly, or if other regulatory pushes change in unexpected ways.”

The final MYs 2027-2032 CAFE Rule rejected the allegation that NHTSA “intended to backstop” an electrification agenda or “mandate” EV sales. However, as noted above, when CAFE standards reach certain stringency levels, compliance increasingly entails boosting sales of BEVs and PHEVs. NHTSA’s MY 2027-2032 standards are stringent enough to drive electrification.

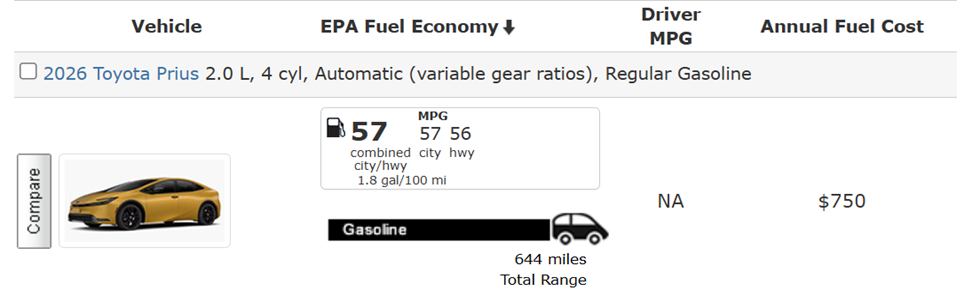

Consider, again, Toyota’s top-of-the-line Prius hybrid. Its CAFE rating is 57 mpg.

Toyota also manufactures hybrids and non-hybrids with lower mpg ratings, such as the Crown Hybrid AWD, rated at 41 mpg, and the non-hybrid Corolla (1-mode TM), rated at 35 mpg. However, even if all Toyota passenger cars were to achieve the mpg of the Prius hybrid shown above, the fleet average would fall short of the final rule’s MY 2032 standard (61.1 mpg).

Absent breakthroughs in hybrid technology, compliance would require significant electrification. Legacy automakers would have to sell more BEVs and PHEVs and fewer ICE vehicles. Granted, they could also comply (at least in part) by purchasing CAFE credits from full-time EV companies like Tesla. However, such trading confers windfalls on EV manufacturers.

III. Unlawfulness of coerced vehicle electrification

Major questions: Under the Supreme Court’s major questions doctrine, a regulatory agency must identify a clear congressional authorization when it undertakes to make a policy decision of major economic and political significance. A decision to restructure the US auto industry, restrict the availability of today’s best-selling models, and increase average new car prices by thousands of dollars obviously qualifies as a decision of major importance. Yet no clear authorization for such a policy exists in CAA § 202(a), the EPA’s putative authority for regulating vehicular GHG emissions, or anywhere else in federal law.

In Massachusetts v. EPA (2007), the Supreme Court did not consider authorizing the EPA to promulgate and enforce CAFE-like tailpipe CO2 standards to be a big deal. The Court opined that “there is no reason to think the two agencies cannot both administer their obligations and yet avoid inconsistency,” and was confident granting the EPA jurisdiction over vehicular CO2 emissions would not lead to “extreme measures” such as the Food and Drug Administration’s unauthorized attempt to ban cigarette sales.

Those rosy assurances proved false. After Donald Trump won the November 2016 election, the EPA abruptly abandoned regulatory commitments it had made in the agencies’ 2012 GHG/CAFE rulemaking to “finalize their actions related to MYs 2022–2025 standards concurrently,” and adopted its GHG standards 14 months ahead of schedule with no clue as to what CAFE standards NHTSA might eventually adopt. During the Biden administration, the EPA’s GHG standards became increasingly more stringent than NHTSA’s CAFE standards. Worse, the EPA’s GHG standards increasingly aimed to ban sales of combustion engine vehicles—products of much greater economic significance than cigarettes.

There was in fact reason to expect the “single,” “national,” “harmonized,” “coordinated,” and “consistent” CAFE/GHG standards program touted in the agencies’ 2010 and 2012 vehicle rules to break down. It’s called “climate ambition.” Exalted in executive orders and intergovernmental treaties, climate ambition tends to foster impatience with statutory and constitutional constraints.

The EPA’s de-facto ZEV mandates are based on the same type of unauthorized policy judgement the Court shot down in West Virginia v. EPA (2022). The Court said the EPA may not set emission performance standards for coal power plants based on its judgment “that it would be ‘best’ if coal made up a much smaller share of national electricity generation.” Logically, the EPA may not set tailpipe emission standards based on its judgment that ICE vehicles should be squeezed out of the nation’s automobile market.

Similarly, the EPA’s de-facto ZEV mandates employ the same type of regulatory tactic the Court shot down in West Virginia. The Court said the EPA may not promulgate CO2 emission standards beyond the reach of fossil-fuel power plants to force a shift from coal and gas generation to wind and solar generation. Logically, the EPA may not promulgate tailpipe emission standards beyond the reach of fuel-efficient hybrids to force a shift from liquid-fueled ICE vehicles to battery-powered EVs.

EPCA preemption. As explained above, the EPA had to revive and advance California’s ACC and ACC II programs to make its own de-facto ZEV standards seem aligned with “market trends.” However, California had no right to enforce vehicle emission voided by EPCA.

California and its allies suggest that SAFE I’s categorical reading of EPCA § 32919(a) must be mistaken because Congress, when amending CAA § 209(b) in the 1977 Clean Air Act Amendments, afforded California the “broadest possible discretion in selecting the best possible means to protect the health of its citizens and the public welfare.” For example, the EPA’s ACC II waiver decision document quotes all or part of that statement a full dozen times. It also cites two seminal DC Circuit Court decisions, MEMA I (1979) and Ford Motor Co. v. EPA (1979), which invoked California’s “broadest possible discretion” to uphold the state’s vehicle emissions policies.

That narrative crumbles upon examination. The phrase “broadest possible discretion” is not in CAA § 209(b), or any other provision of law. It comes from the House Conference Committee Report on the 1977 CAA Amendments. It is rhetorical assertion rather than statutory explication. If “broadest possible discretion” is a core meaning of CAA § 209, why didn’t Congress put it in the statute? As Justice Scalia emphasized, the main source for understanding a statute is the statute itself. Report language can be illuminating but sometimes it is just spin.

More importantly, there is a shocking disproportion between the discretion approved by the DC Circuit in 1979 and California’s current regulatory ambitions. In MEMA I, the court upheld California’s decision to adopt weaker-than-federal carbon monoxide (CO) standards so that automakers could implement stronger-than-federal nitrogen oxides (NOX) standards. In Ford Motor Co., the court upheld California’s revision of manufacturer warranties to encourage (not compel) the development of more durable emission control devices. The court said Congress intended for California to be a “pioneer” and “laboratory of innovation,” not an industrial policy czar for climate and cars.

California and its allies also contend that when reviewing a CAA § 209(b) waiver request, the EPA may not—or at least need not—consider anything except the three decision criteria contained in the provision, which do not include consistency other statutes or the US Constitution. That claim is incorrect.

California seeks § 209(b) waivers so that it and allied states may include California vehicle emission standards in their National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) state implementation plans (SIPs). CAA § 110(a)(2)(E) requires each SIP to provide “necessary assurances” that no “portion” of the plan is “prohibited under any provision of federal or state law.” CAA § 110(k)(1)(A) requires the Administrator to “determine whether the plan submission complies with the provisions of this chapter.” The Administrator may not lawfully fail (much less lawfully refuse) to consider whether ACC II is prohibited by EPCA.

IV. Coup de Grace: SAFE III’s literal reading of EPCA §32902(h)

NHTSA’s rollback of CAFE standards is based on its judgment as to the maximum feasible levels manufacturers can achieve, balancing four key factors: technological feasibility, economic practicability, the nation’s need to conserve energy, and the effect of other federal regulations on fuel economy. The balancing takes account of current and projected circumstances. For example, diminishing returns from higher fuel economy standards, rising domestic petroleum production, an “already unaffordable new car market,” and large percentages of vehicles that could not meet the MY 2022 CAFE standards militate against heavily weighing the nation’s need to conserve energy.

However, what chiefly drives the CAFE reset is a new strict interpretation of EPCA § 32902(h). In determining maximum feasible fuel economy levels, “the Secretary of Transportation—(1) may not consider the fuel economy of dedicated automobiles; (2) shall consider dual-fueled automobiles to be operated only on gasoline or diesel fuel; and (3) may not consider … the trading, transferring, or availability of [CAFE compliance] credits.”

As NHTSA explains in its June 2025 interpretative rule, the meaning of those restrictions is “unequivocal” as well as “clear” from the legislative history. For example, the interpretive rule quotes from Rep. John Dingell’s (D-MI) statement on the Conference Report for S. 1518, the Alternative Fuels Act of 1988. Dingell states: “It is intended that the Secretary will not take into account in any such assessment [of maximum feasible fuel economy] the extent to which manufacturers have produced alternative fueled vehicles.” He further states: “It is intended that this examination will be conducted without regard to the penetration of alternative fueled vehicles in any manufacturer’s fleet…” In short, Dingell affirms that § 32902(h) means what it says.

The problem, NHTSA explains, is that in 2012, 2020, 2022, and 2024, the agency “took the position that it could account for the factors prohibited from consideration in section 32902(h) by using a narrow construction of that provision.” Under that narrow—actually, loose—construction, NHTSA may consider the market penetration of alternative and dual-fueled vehicles if rising sales is due to factors other than NHTSA’s CAFE standards, and if the rise is projected for years before or after the period for which NHTSA is setting standards. Under the loose construction of § 32902(h), NHTSA may consider BEV and PHEV sales induced by the EPA and California’s vehicle emission programs. Thus, the loose construction has the effect of increasing the stringency of CAFE standards that can be considered maximum feasible.

The Biden NHTSA also considered the availability of compliance credits in years outside the model years for which the agency is setting CAFE standards. That, too, made stringent standards appear more affordable, especially the large credit values awarded for EV sales. It significantly increased fuel economy requirements for traditional gasoline- or diesel-fueled fleets.

Loose construction of EPCA § 32902(h) was the permission slip for NHTSA’s electrification backstop—the agency’s adoption of fleet average standards exceeding the mpg performance of the best-performing Prius hybrid.

It was counterfeit. NHTSA may not consider the fuel economy of dedicated vehicles “in any respect at any point in the process for setting fuel economy standards.” Ditto for credit trading. CAFE standards “must be feasible and practicable for gas-powered vehicles without regard to any reliance on non-gas-powered alternatives or compliance credits.”

Accordingly, NHTSA “proposes to remove consideration of prohibited technologies and credits from every aspect of the standards development process to bring the program back within its statutory constraints.” SAFE III CAFE standards will be maximum feasible within the “unequivocal” strictures of EPCA § 32902(h).

NHTSA also proposes to eliminate the inter-manufacturer credit trading system, starting in MY 2028. There will no longer be a legitimate need for trading because automakers will not be subject to unachievable standards. Manufacturers will be able to focus more on consumer preferences and less on regulatory complexities.

V. Conclusion

CEI congratulates NHTSA for its penetrating analysis of the regulatory and market distortions wrought by years of impermissible interpretation of EPCA § 32902(h). Thanks to the Trump administration and Congress, America is on the cusp of liberating the US auto industry from decades of overregulation. Congress and President Trump repealed the waiver for California’s ACC II program. Administrator Lee Zeldin has proposed to repeal the EPA’s motor vehicle GHG standards. Now, with SAFE III, NHTSA proposes to terminate and preclude the agency’s unauthorized participation in forced vehicle electrification.

If all goes according to plan, America can look forward to an era of more affordable automobiles, more choices for consumers, and a more competitive auto industry.

An additional reform would help secure this grand achievement. NHTSHA should rescind the Biden administration’s SAFE I Repeal Rule and adopt a new interpretive rule clarifying EPCA’s categorical preemption of state policies that regulate or prohibit tailpipe CO2 emissions.

Sincerely,

Marlo Lewis, Ph.D.

Senior Fellow

Competitive Enterprise Institute