Party Bias in EPA’s Power Plant Rule?

What’s the main difference between EPA’s final rule to regulate carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from state electric-power sectors—the so-called Clean Power Plan (CPP), released August 3—and the draft rule, published in June 2014?

“The media have focused on modest tweaks to non-binding national goals—emissions are now expected to drop 32 percent by 2030, versus 30 percent in the draft, and coal is expected to provide 27 percent of our power instead of 31 percent—but those aren’t the changes that matter,” argues Politico reporter Michael Grunwald.

What does matter? The changes to states’ legally-binding emission-reduction targets, which have “serious political implications.” The final rule is more aggressively anti-coal than the draft rule:

The original draft took it easiest on states with the heaviest reliance on dirty fossil fuels – states that nevertheless complained the most about Obama’s supposedly draconian plan. The final rule cracks down much harder on those states, while taking it much easier on states that are already moving toward cleaner sources of electricity.

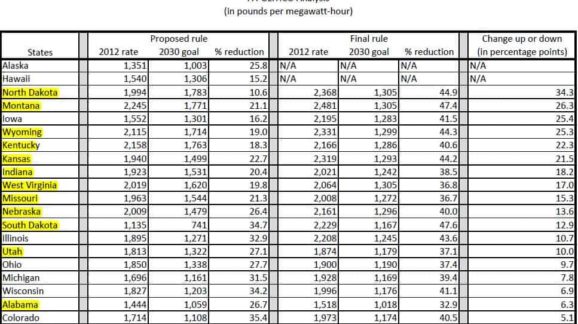

Check out this excellent chart compiled by my colleague Alex Guillen. North Dakota would have been required to cut emissions just 10.6 percent to comply with the draft rule, the least of any state; it will have to cut emissions 44.9 percent to comply with the final rule, the most of any state except for similarly fossil-fueled Montana and South Dakota. Coal-rich Wyoming, Kentucky, West Virginia and Indiana were also among the biggest losers in the revised plan. Meanwhile, the states that are already greening their grid – led by Washington, Oregon and New York – were the biggest winners in the final rule.

Is there also a partisan thrust to this pattern? The title of Grunwald’s article calls the CPP a “whack at red states.” The article itself, however, does not use the terms “Red State” and “Blue State.”

So let’s look at how the draft and final rule targets compare in states won by Mitt Romney (“Red”) and those won by President Obama (“Blue”) in the 2012 presidential election.

The chart below is the one compiled by Grunwald’s colleague. I have shaded in yellow the name of each Red State.

Nine of the 10 states with the biggest increases in regulatory stringency are Red States. Seven of the 10 with the biggest decreases in regulatory stringency are Blue States.

Compared to the draft rule, 13 Red States have tougher targets and 8 have more lenient targets in the final rule.

Compared to the draft rule, 10 Blue States have tougher targets and 15 have more lenient targets in the final rule.

While those numbers are interesting, it is important to realize that the CPP inherently whacks Red States. Why? It vitiates their freedom to adopt low-cost, pro-growth energy policies—policies that help make them attractive places for Americans to work, invest their money, and register to vote.

As discussed in more detail elsewhere, the CPP is not just another bureaucratic power grab. It is potentially an Archimedean lever for transforming American politics.

In brief, the CPP is a plan to cartelize state energy policies along the product lines of California’s Global Warming Solutions Act and the Northeast States’ Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). In general, to meet their CPP emission-reduction targets, states without renewable energy mandates will have to adopt them, others with renewable energy quota will have to increase them. Grid operators will have to replace traditional “economic dispatch” with “low-carbon dispatch,” giving priority to generating units with the lowest emissions rather than those with the lowest cost. EPA helpfully explains that cap-and-trade programs, especially if administered through multi-state compacts, can help states comply.

Once the CPP is locked in through federally-enforceable implementation plans, households and businesses will be less able to vote with their feet against “progressive” (Blue State) energy policies. The CPP will thereby remove an important check—a shrinking tax base—on regulatory excess. Politicians still advocating pro-growth (Red State) energy policies within an EPA-administered policy cartel could become a dying breed.

Consider also that many national lawmakers learn their chops in state government, and most politicians are weathervanes anyway. If, between now and 2030, the vast majority of states are “cooperating” with EPA on climate policy, fewer and fewer advocates of Red State energy policy will be elected to Congress. Congressional resistance to cap-and-trade, national renewable energy quota, and UN-sponsored climate treaties would be increasingly hard to sustain.

Fortunately, resistance is not futile. The CPP is unlawful in numerous ways making it a prime target for litigation by coal states, energy-intensive industries, and free-market public-interest groups. The CPP is also likely to be a hotly contested issue in the 2016 elections. If Red State politicos win a clean sweep, they should be able to upend EPA’s power grab.