The 2019 Unconstitutionality Index

Even in an administration attempting to cut regulation, the number of rules from hundreds of federal agencies (nobody really knows exactly how many) will vastly outstrip the number of laws that Congress passes.

Even in an administration attempting to cut regulation, the number of rules from hundreds of federal agencies (nobody really knows exactly how many) will vastly outstrip the number of laws that Congress passes.

That represents the triumph of the Administrative State over the Constitution, and this it even holds under President Trump.

The year 2018 and the 115th Congress have drawn to a close, so let’s look at Trump’s second calendar year. The 116th Congress gets underway

The 116th Congress gets underway January 3, 2019, in the wake of the Trump administration’s touting notable regulatory rollback achievements in a 2018 Regulatory Reform Status Report on the adminstration’s “one-in, two-out” goals for regulation. It’s available on the Unified Agenda web page, although it must be said that it becomes harder over time, for a president acting alone, to streamline anything.

Liberals who didn’t want regulations cut regardless were not impressed in the first phase, droning that Trump “claims credit for some regulatory actions begun under Obama,” and that the “deregulatory list ranges from bird feathers to grizzlies.”

The entrenched regulatory enterprise clearly has enormous staying power with which Congress has yet to grapple. In Trump’s first year, Congress did use the resolution of disapproval process established by the Congressional Review Act (CRA) to eliminate 16 Obama-era. “midnight rules”; the problem, though, was that hundreds were eligible. While the 115th Congress passed major reforms like the Regulatory Accountability Act, nothing apart from CRA resolutions ever got through the Senate.

With that backdrop, let’s look at rules vs. laws.

Congress’s 291 Laws

There were 97 public laws passed in 2017, the first session of the 115th Congress.

In 2018, the 2nd half of the 115th Congress passed and the president signed 180 laws according to the tally as of December 29 on the Government Publishing Office’s archive of public laws (my preferred archival resource). The archive is complete through the renaming of the Stop Trading on Congressional Knowledge Act, enacted Nov 3.

In addition, a Govtrack legislative search yields (an astonishing) 111 more enacted through December 21.

So Congress passed, by this preliminary count, 291 laws in 2018.

Among such annual tallies one finds legislative initiatives ranging from naming post offices and community centers after politicians and dignitaries, to major reauthorizations of agencies and mega-giga-programs like the Farm Bill.

I must pause here to reflect on those who say Congress doesn’t “get things done.” The only other calendar years since 1992 with more laws enacted were 2000 (with 410); 2004 (with 299); and 2006 (with 321).

But you don’ t want to know that from me; as a small-“l”-libertarian I prefer a Congress that gets things undone.

However, as usual—heavy 2018 legislative load that we must acknowledge notwithstanding—the unelected federal bureaucracy was far busier making laws than Congress was.

Agencies’ 3,367 Rules

During calendar year 2016 under Barack Obama, agencies broke records with a 95,894 page Federal Register. Within those pages, agencies issued 3,853 rules and regulations. By contrast, the 2017 calendar year Federal Register ended at 61,308 pages, the lowest count in a quarter century.

As 2018 wound down, the Federal Register ended at 68,082 pages. Within those pages, agencies issued a total of 3,367 rules.

Note that these page and rule counts are the preliminary tallies from the National Archives’ Federal Register database; a final reckoning will be issued within a couple months.

Rules have numbered well over 3,000 per year for decades. But there are hundreds upon hundreds of rules that agencies (rightly or wrongly) do not deem to rise to the level of “significance” targeted in the two-for-one executive order campaign. Federal Aviation Administration airworthiness directives numbering in the hundreds are a classic example.

The Unconstitutionality Index

Obviously in any given year, the specific rules agencies issue unlikely to be tied to the laws enacted that very same year. That probably would almost never be the case.

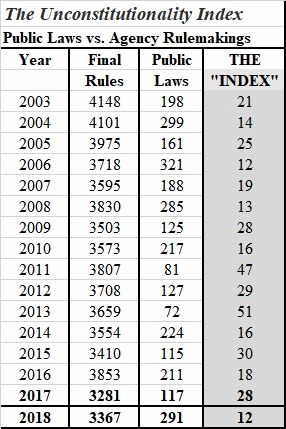

Nonetheless, in terms of flow, federal agencies in 2018 issued 12 rules and regulations for every law Congress passed (3,367 agency rules, compared to Congress’s 291 laws).

The Index had been 28 at the end of Trump’s first year, 18 in Obama’s last year. I like to call this ratio The Unconstitutionality Index; it’s simply the multiple of agency rules over the number of laws from our elected Congress.

As we’ve described before, there’s no pattern to any of this, since the numerators and denominators can vary widely. The multiple can be higher with fewer laws, or with more regulations, holding the other constant.

The point, though, is that the unelected personnel of agencies do the bulk of lawmaking in America, not Congress—no matter the party in power.

The chart below depicts the Index going back to 2003 (you can go back earlier in the Ten Thousand Commandments roundup in Historical Tables, Part J).

For what it’s worth, during Bush’s eight years, the multiple averaged 20, while Obama’s eight averaged 29.

Further, Trump’s aim is eliminating rules, but alas, eliminating a rule requires issuing another rule.

Still, as far as the Index is concerned, whether you’re adding rules or trying to take them away, unelected officials make most law. One might say the march toward civilization and human liberty is a march toward not doing that anymore.

Until then, the ratchet largely goes only one way and the administrative state grows, Legislators of both parties have relinquished their constitutional authority and tolerate the Administrative State. That is the wrong kind of bipartisanship.

Now, having said all this, there are yet hundreds of agency guidance documents and various forms of regulatory dark matter (guidance documents, memoranda, notices, letters, and other proclamations) that carry the lawmaking of the unelected to even greater levels. These would send the Index higher if included.

The Trump administration through a new executive order, should more explicitly recognize and restrain guidance. As it stands, lawmaking without elected representatives’ involvement goes well beyond what the Index now captures.

Now it’s the Democrat-dominated 116th Congress’s turn to develop a regulatory liberalization agenda with the president. The White House can’t (and shouldn’t) do all of it alone.

Happy New Year anyway!

In all seriousness, though, the most important regulatory reform measures of the past, like the Congressional Review Act itself, were overwhelmingly bipartisan upon passage.