Appeals court rejects DOE’s attempt to eliminate fast dishwashers

Photo Credit: Getty

The days of dishwashers with four-hour cleaning cycles may be coming to an end. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals repudiated the Biden administration’s attempt to prohibit faster dishwashers on Monday. The Court described the government’s position as arbitrary, capricious, and bordering on frivolous—which is much harsher language than judges generally use about lawyers.

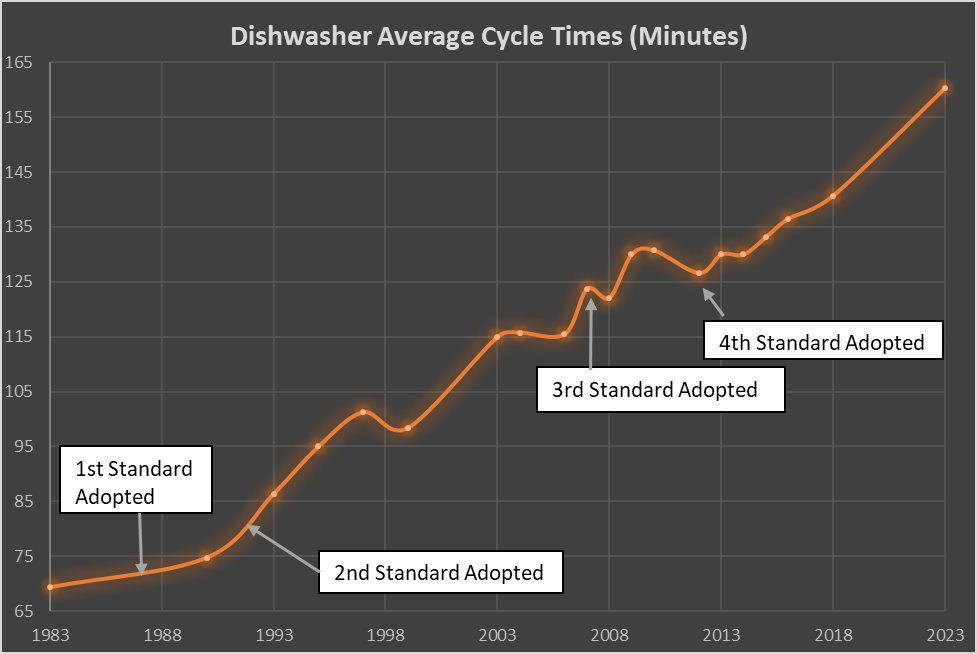

The Competitive Enterprise Institute first proposed the faster dishwasher regulations more than five years ago, in response to the way that federal regulations limiting water and energy doubled the time dishwashers took to operate. Indeed, the government admitted it. The Department of Energy stated: “To help compensate for the negative impact on cleaning performance associated with decreasing water use and water temperature, manufacturers will typically increase the cycle time.” Experts outside of CEI agreed that It’s the Government’s Fault Your Dishwasher Cycle Is 2 or 3 Hours Long and that it was the result of energy and water restrictions. In turn, this increased time caused people to hand wash dishes.

In 2018, on behalf of the Competitive Enterprise Institute, I submitted a proposal to the Department of Energy for faster dishwashers that can use more energy and water for greater speed. We proposed that DOE create new regulations based on the statutory language in 42 U.S.C. § 6295(q). Typically, standards can only be made higher or more stringent due to the limits in § 6295(o)(1), but § 6295(q) creates an exception that allows a “lower” level of efficiency or energy use if the new subclass of products have a “capacity or other performance-related feature which other products within such type (or class) do not have” that justifies the lower standard.

DOE posted the petition on the federal register and allowed the public to comment on the proposal without supporting or opposing the idea. In the comments by individuals, 16 opposed the new class of dishwashers, 41 were neutral, and 2,187 supported this new type of dishwasher. That overwhelming show of support by the public convinced DOE to accept our petition and adopt those regulations in October 2020. DOE liked the idea so much that it made a similar regulation for clothes washers and driers on their own initiative.

On the day of his inauguration, President Biden ordered DOE to reconsider the creating of these new classes of faster dishwashers, clothes washers, and driers. The Biden administration’s DOE repealed the new class of faster dishwashers. It claimed that the Trump administration had failed to consider the appropriate standard when issuing the new class of dishwashers.

A dozen states filed a lawsuit seeking to stop the repeal of these new types of dishwashers, and CEI wrote an amicus brief supporting those states. The Court’s first job was determining if the states had standing to sue—if the repeal injured them. The states claimed they had standing because they own and operate residential dishwashers through a variety of state programs; therefore, because their choice about which dishwasher to buy was limited by the repeal, they were harmed.

The Court found that the states did have standing, based partly on the results of previous litigation from the Competitive Enterprise Institute. CEI had sued NHTSA and established our standing on the fact that NHTSA was preventing people from buying bigger and less fuel-efficient vehicles. The D.C. Circuit had found that standing in that case rested on the limitation of the consumer’s choice. Ultimately, the Fifth Circuit found that the states had standing in the dishwasher case on the same basis.

Getting to the merits, the Fifth Circuit rejected DOE’s argument on many grounds:

(1) The Court disputed that DOE had the authority to regulate water use in dishwashers and clothes washers.

(2) Even if DOE did have that authority, it should have considered whether its regulations limiting per-cycle water and energy use actually increased total water and energy use, due to such factors as handwashing and people running the dishwasher multiple times to clean dishes.

(3) DOE failed to consider whether cycle time was an important performance characteristic and failed to provide a reasoned explanation for how its actions would preserve cycle time.

(4) Even if the Trump rules were illegal, DOE failed to consider possible alternatives to repealing them entirely. A failure to consider other options due to internal time and resource constraints was contrary to what DOE had said weeks earlier, and it needed to explain that inconsistency. The many alternatives open to DOE included:

a. Conducting what it considers the proper analysis that it claims was lacking before,

b. Issuing the energy conservation standards that it claims were required to create the new class of faster dishwashers, or

c. Creating a separate class for faster dishwashers but setting them to the same standard, so that when future increases in efficiency occur, the faster models would be allowed a lower rate of increase in efficiency in the future.

(5) The Court also rejected the post hoc rationalization of DOE that the Trump administration had violated procedural requirements. As the Court noted, the agency must defend its actions based on its explanation of those actions at the time, and the Biden administration’s claims about procedural violations were only produced later. Furthermore, the Court noted that the Biden administration’s claims about a failure of consideration bordered on the frivolous, as these matters were discussed throughout the rule the Trump administration had issued.

These arguments cover a lot of ground, but from the perspective of the future, the most interesting rulings are the first three. If DOE cannot regulate any water efficiency rules outside of showerheads, faucets, water closets, and urinals, then the Court has decided to shrink an authority that DOE has improperly exercised for decades.

An examination of how consumer behavior has been altered by shifting standards would be a sea change in how DOE determines the efficiency of appliances. Many ideas have good intentions but create bad outcomes, and some appliance regulations probably fall into this category. The goal of limits on the per-cycle use of water and energy is presumably to save water and energy. But in reality, those limits change how consumers operate the appliance. A degradation in performance might cause the user to run the dishwasher multiple times, flush the toilet more often, or take longer showers to get clean.

If the products worked better with less water, the manufacturers have an incentive to make that change. But the burden of regulation may be so heavy that handwashing or other changes in consumer behavior use more total energy and water than if the regulation had never been enacted at all. It’s difficult to determine costs and benefits of regulations if we don’t know what the actual savings of water and energy are that spring from these regulations. And that data isn’t even evaluated by the DOE at all.

Finally, the Court recognized that cycle time is an important characteristic of dishwashers and other appliances. If DOE realistically evaluated the impact its regulations have on cycle time and considered how to minimize their harm, that would be a drastic change. Indeed, DOE has acknowledged that cycle time is increased by its regulations. Still, it doesn’t attempt to measure that increase or do anything to mitigate its harms.

The ultimate result of the decision is that the Court told the agency to do its job right this time. The Court didn’t vacate the rule, so faster dishwashers won’t be allowed for now, but this opinion will force DOE to explain itself. Here’s a summary of the big questions that the agency will be forced to answer during the process of creating a new rule:

(1) Can DOE create any water efficiency standards at all for products outside of showerheads, faucets, water closets, and urinals?

(2) Why does 42 U.S.C. § 6295(q) say it allows a “lower” efficiency or energy use if DOE says the statute can’t permit that?

(3) Does the increase in cycle time caused by lower energy and water limits cause enough people to switch to handwashing in a way that causes an increase in total energy and water use?

(4) Can DOE implement alternatives to repealing the Trump rules? For instance:

a. Going through what it considers the proper analysis that it claims was lacking before,

b. Issuing the energy conservation standards that it claims were required to create the new class of faster dishwashers, or

c. Creating separate classes for faster dishwashers but setting them to the same standard, so that when future increases in efficiency occur, the faster models would be allowed a lower rate of increase in efficiency in the future.

(5) Does DOE have a substantive response to the actual arguments presented by the Trump administration concerning § 6295(q) and § 6295(o)(1)?

Will DOE listen to the public – which has asked and asked for faster dishwashers – or will it continue to ignore its pleas? I hope that, after this new regulatory process, the era of painfully slow dishwashers (and other appliances) will be over. That day can’t come soon enough.