CBO likely overestimates effects of Medicaid reforms

Photo Credit: Getty

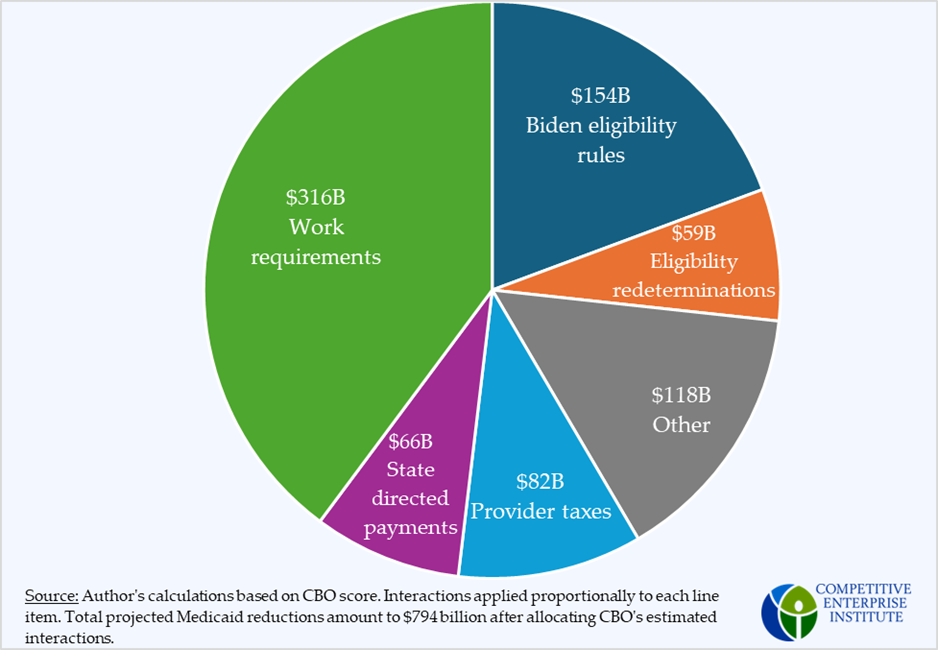

Yesterday, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released its estimates of the costs, both financial and in coverage, of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA). It estimates that the Act will reduce projected Medicaid spending by $794 billion over the next ten years and increase the number of uninsured Americans by 10.9 million. In addition, CBO has estimated a total of 16 million additional uninsured by 2034 when you include expiring provisions of Obamacare and a proposed CMS rule. The chart below shows how the CBO’s Medicaid spending reductions are split across the major elements.

Of the major provisions, only the work requirements should be classified as a significant operational change to Medicaid that would directly affect eligible beneficiaries. The moratorium on provider taxes and revision of state directed payments are both new limitations put in place to arrest states’ growing abuse of accounting gimmicks. Eligibility redeterminations are merely an increase in the frequency of checking that the Medicaid expansion population continues to qualify for the program. The $154 billion categorized as “Biden eligibility rules” accounts for the rolling back of rules put in place during the Biden administration which led to increased enrollment compared to historic norms.

States can make up most of the difference

States have been contributing less to Medicaid in recent years, while at the same time increasing enrollment and payments to providers in ways that boost federal spending on the program. As a percentage of GDP, states are contributing less to Medicaid than they were in the 2010s. If states increased their contributions back to their historical max, they would contribute an additional $628 billion to Medicaid over ten years. That amount would cover 80 percent of the reductions in the OBBBA. Since many of the provisions being debated wouldn’t directly reduce the number of Medicaid beneficiaries (like provider taxes, state directed payments, and redeterminations), states have the fiscal space to ensure that losses in coverage for those eligible would be minimal.

Effects on coverage

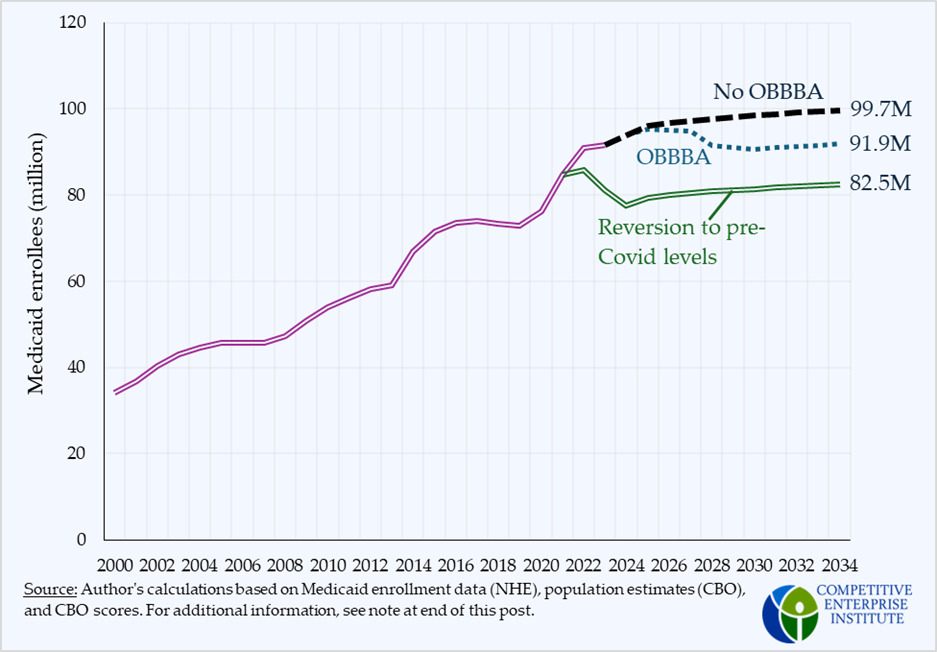

CBO estimates that the Medicaid provisions, specifically, would increase the rate of uninsured by 7.8 million people in 2034. While there are many reasons to believe that these are overestimates, notably, this projected reduction would still be smaller than the post-COVID increase in the Medicaid program.

During the pandemic, enrollment grew by nearly 20 million due to relaxations of eligibility rules and redeterminations and other efforts to grow Medicaid. The Medicaid-boosting provisions are only now being unwound, and the OBBBA would further undo them. Despite that, however, by 2034, Medicaid enrollment would still be nearly 10 million people greater than it would have been if it had stayed proportional to the population. The OBBBA is merely putting Medicaid back on its pre-COVID track, but only partially.

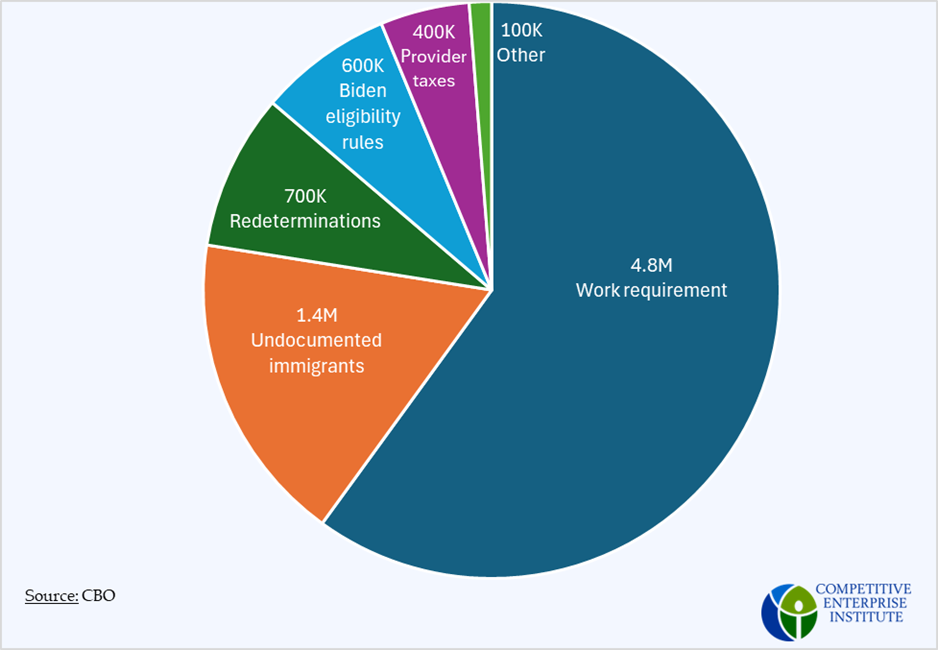

In a supplemental letter, CBO broke down their estimate into six categories. Work requirements are responsible for the largest proportion of the projected reductions in the insured. The second largest proportion comes from undocumented immigrants.

There are several reasons to believe that CBO’s estimates won’t come to fruition. The largest portion of the 7.8 million comes from the Medicaid work and service requirement. Projections of the effect of the work requirement are based on two states’ experience—Arkansas and Georgia. These are the only two states that have introduced any work requirements. However, neither of these states’ experience provides the information that would be necessary for accurate, long-term projections.

The Arkansas work requirement was in effect for less than a year. It went into effect on June 1, 2018, and a lawsuit was filed on August 14 of the same year. The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia ruled in March of 2019 that it was unlawful, and its implementation was suspended. An ostensibly permanent policy, which was challenged within 75 days of its going into effect, and operating under a Sword of Damocles for seven of the ten months it was in existence is not going to be very informative for researchers or policymakers who want to know what the effects of a permanent, national policy would be.

Critics of the work requirement argue that the work requirement will be mostly ineffective at promoting work because a large proportion of Medicaid beneficiaries are already employed. Any reductions in coverage will come from burdensome administrative tasks and paperwork that beneficiaries won’t perform. However, there’s good reason to believe that administrative burdens on those who are eligible will be minimal and are overstated, even in the Arkansas case.

More than 70 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries are enrolled through a managed care organization—a private insurer that manages the health care for beneficiaries. These organizations differ from the traditional fee-for-service model in that the organizations enroll the beneficiary, receive a monthly payment from the state, and are then responsible for financing the health care of the beneficiary.

These organizations have every incentive to enroll as many people as possible, regardless of eligibility, because it means additional revenues. Over time, one would expect these organizations to minimize any paperwork burden to ensure maximal enrollment and maximum revenue. The short duration and narrow geographic scope of the Arkansas experience didn’t allow MCOs to adjust fully, but it would very likely be significant at a national level.

Predicting the future is difficult, and even more so when you must predict interactions across multiple organizations at a large scale for a policy that has never been implemented. CBO is doing its best with the information it has, but given the complexity of the health care system and the lack of experience with these policies, it is highly unlikely that its models will be adequately account for the major provisions in the OBBBA.

Note on coverage projections

Medicaid coverage estimates, both historic and projected, are subject to moderate variation. Because recipients come on and off Medicaid throughout a given year as their circumstances change, Medicaid enrollment changes, too. As a consequence, estimates of Medicaid enrollment might be of beneficiaries who are ever enrolled at all during the year, or at a point in time. The latter case will result in smaller enrollment figures. Additionally, CBO projections appear to be undergoing large fluctuations. For example, in February 2024, CBO projected that federal expenditures for Medicaid would be $898 billion in 2034. In its January 2025 edition of the same projection, CBO’s projection for 2034 rose by $88 billion to $986 billion; close to a 10 percent increase. The ten-year projection went up by $1.4 trillion. The projected enrollment in the graph is based on National Health Expenditures estimates historically, carrying forward projections based on percentage of population. The CBO estimates of enrollment are lower than this, but were not used because CBO’s enrollment projections were only available from the 2024 projections, which underwent major revisions in 2025.