EPA’s new powerplant rule is the Clean Power Plan on steroids

Photo Credit: Getty

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) yesterday announced its final rule establishing carbon dioxide (CO2) emission performance standards for existing coal powerplants and new natural gas powerplants. Although the final rule differs from the EPA’s May 2023 proposed rule in various ways, the big picture remains the same. The rule establishes a 90 percent carbon capture and storage (CCS) requirement that will drive coal generation out of the nation’s electricity mix. This is the Clean Power Plan on steroids. The rule defies the Supreme Court’s ruling in West Virginia v. EPA. It is an unlawful assault on affordable energy and grid reliability.

Under Section 111 of the Clean Air Act, emission performance standards are to reflect the “best system of emission reduction” (BSER) that has been “adequately demonstrated,” taking into account costs, energy requirements, and non-air environmental impacts. Whether CCS is “adequately demonstrated” has been a bone of contention for many years.

CCS is an energy and water-intensive process that adds significantly to the cost of electricity generation. Despite decades of R&D and billions of dollars in taxpayer and ratepayer subsidies, only two commercial CCS coal powerplants operate in North America: Petra Nova in Texas and Boundary Dam in Canada. Only Boundary Dam was operational during the comment period. Both projects were built with substantial subsidies and plagued with technical difficulties. Although Boundary Dam can capture up to 90 percent of its CO2 emissions, its actual capture rate as of January 2022 was 75-80 percent.

The final rule also imposes a 90 percent CCS requirement on new baseload natural gas power plants. No utility scale natural gas CCS plant exists today. Only one small-scale facility was ever built – Florida Power & Light’s 40 MW CCS gas plant in Bellingham, Massachusetts. It closed in 2005. Not exactly a broad technological base on which to predicate an industry-wide 90 percent carbon capture requirement.

The Biden administration aspires to decarbonize US electric generation by 2030. However, wind farms do not produce power during wind droughts, which can last a week or more, and solar stations produce little power on cloudy days and none at night. Absent breakthroughs that dramatically decrease the cost and increase the performance of battery storage, grid reliability will depend on the availability of electric power generated from coal, gas, nuclear power, or dams.

That may be why the EPA decided not to impose a 90 percent carbon capture requirement on existing baseload natural gas powerplants.

Let’s quickly review how the final rule differs from the proposed rule, with an eye to the rule’s potential impacts on electricity cost and reliability, and its legal status under West Virginia v. EPA.

In the proposed rule, baseload coal powerplants that don’t commit to close by 2039 must capture 90 percent of their CO2 emissions by 2030. The final rule extends the 90 percent CCS deadline until 2032. That does not change any electric utility’s bottom line. It just means the owners of those facilities have two more years to sell the furniture and pack their boxes.

In the proposed rule, new natural gas powerplants must capture 90 percent of their CO2 emissions by 2035. The final rule moves up the deadline to 2032. Presumably, even fewer new baseload natural gas powerplants will be built.

Indeed, to qualify as baseload in the proposed rule, a natural gas powerplant had to run at least 50 percent of the time. The final rule lowers the threshold to 40 percent. So, compared to the proposed rule, fewer new baseload natural gas powerplants will be able to avoid the 90 percent CCS requirement, and all will have to meet it three years sooner.

In the proposed rule, new baseload gas units had the option to co-fire with 96 percent “green” hydrogen (hydrogen produced by electrolyzing water with renewable energy) as an alternative to achieving 90 percent carbon capture. The final rule drops that option. Apparently, even the EPA acknowledges that its “adequately demonstrated” determination for green hydrogen co-firing could not pass the laugh test. After all, if a so-called natural gas powerplant co-fires with 96 percent hydrogen, it is really a hydrogen powerplant that co-fires with 4 percent natural gas.

In the proposed rule, the 90 percent CCS/96 percent co-firing requirement applied to existing baseload natural gas powerplants as well as new facilities. The final rule defers the existing source requirements to a future rulemaking. We should not be surprised if the EPA again proposes 90 percent CCS for existing gas generation in a second Biden administration.

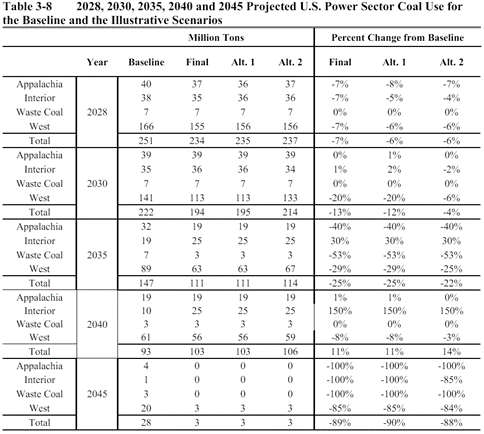

In sum, the final rule is more stringent than the proposed rule in some respects, and less stringent in others. Both are far more aggressive than the Clean Power Plan (CPP), which the Supreme Court vacated in West Virginia. The CPP established an emission performance standard for existing coal powerplants of 1,305 lbs. CO2/MWh – approximately 24 percent lower than the emission rate of efficient supercritical coal plants then in service (1,720 lbs. CO2/MWh). The EPA now demands a 90 percent reduction in CO2 emissions from existing baseload coal powerplants. The CPP projected a reduction in coal generation market share from 38 percent in 2014 to 27 percent in 2030. The new rule projects an 89 percent reduction in power sector coal use in 2045, relative to the current policy baseline.

Whether coal and gas powerplants should be forced out of the nation’s electricity supply system is undeniably a major question of national policy. The EPA may not decide that question absent a clear statement of congressional authorization. As the Supreme Court ruled in West Virginia, Section 111 of the Clean Air Act does not come “close to the sort of clear authorization required” to “delegate authority of this breadth to regulate a fundamental sector of the economy.”