Exposed: Bloomberg’s Anti-Tobacco Meddling in Developing Countries

Photo Credit: Getty

Back in February I wrote a piece for Inside Sources titled “Bloomberg’s Philanthro-Colonialism: A Threat to Global Health and Science,” criticizing the behavior of anti-tobacco groups funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies in low- and middle-income nations (LMICs). For those unfamiliar with Bloomberg’s initiative against tobacco—now expanded to target the use of any non-pharmaceutical nicotine—the headline might come across as sensationalistic. But internal communications from the group orchestrating that initiative, recently obtained by CEI, show the true extent of its influence, which reaches throughout all levels of civil society, media, and even government, and appears aimed at imposing its will on the developing world, regardless of the needs and interests of the people who live there. Worse, it often provides funding to foreign government entities, seemingly without much regard for those governments’ level of respect for liberal values and democratic governance.

The documents, provided by an anonymous source, comprise 128 pages of the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids’ (CTFK) 2017 strategy for LMICs. CTFK is one of the main outfits through which Bloomberg channels anti-tobacco money. Its stated mission is to cultivate and finance anti-tobacco efforts around the world. But its private plans reveal the scope and pervasiveness of its influence, particularly in developing regions. By building a vast network of “partners” that includes some of the most influential people and institutions in a society, including government agencies and authoritarian regimes, CTFK generates what appears like an organic consensus—a cacophony of ostensibly independent voices all clamoring for the same tobacco control policies. In reality, it is a highly synchronized chorus of interdependent interests, coordinated from afar.[1]

Neither Bloomberg nor its direct recipients conceal their financial ties. Bloomberg Philanthropies maintains a database that allows anyone to explore where its more than $700 million in tobacco grants have gone over the years. The largest of these beneficiaries, like CTFK, the World Health Organization (WHO), the CDC Foundation, and the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (the Union), are similarly open about their relationship with Bloomberg. Where things get murkier is in how those beneficiaries utilize that funding to influence key players. The existence and effects of this sort of cooperation are, if not disguised, so indirect they are often imperceptible. Based on CTFK’s internal plans, as well as other information that has recently come to light, that appears to be the point.

The overarching theme of CTFK’s approach is: We know what’s best. The bulk of its activities are aimed at convincing governments in low- and middle-income countries to go along. The plan not only rejects, but actively intends to fight any proposed approach to tobacco regulation that might take into consideration the unique needs or values of the people who live there.

As with all Bloomberg-funded anti-tobacco outfits, CTFK exclusively pursues a zero-tolerance approach to any and all use of “tobacco,” and demands the uniform application of aggressive tobacco laws dictated by international “authorities” (themselves and the other members of Bloomberg’s network). As experience has shown, zero-tolerance approaches don’t work, and often backfire.

Zero Tolerance Doesn’t Work

It doesn’t take a science degree to know that what might work with one group may not work with another. Residents of LMICs have different priorities, resources, and access to services or therapies. Their cultural, economic, and geographic environments also factor into how they respond to regulatory changes (e.g. substitution, illicit markets, or homemade products). As such, policies that might reduce smoking in one country may not only fail to reduce smoking in another, but might cause people to engage in even more harmful behaviors.

CTFK’s strategy recklessly ignores these factors. It also ignores the fact that not all forms of tobacco use have the same risks. Thus, despite the overwhelming evidence that noncombustible sources of nicotine (e.g. snus, heated tobacco, e-cigarettes) are radically less harmful and highly effective for smoking cessation, CTFK’s strategy includes demanding that LMICs—where 80 percent of the world’s smokers live and die—treat all tobacco equally, and apply the same high taxes, restrictions, and prohibitions meant to discourage or outright ban tobacco use to these potentially life-saving alternatives.[2]

Funding Governments

To that end, CTFK has endeavored to influence all levels of the political process and its key players in various countries. This includes partnerships and collaborations (often financial) with activists, think tanks, professional associations, media, universities, and governments. At the top, CTFK decides the priorities and the best course of action, while its grantees, sub-grantees, and “partners” aid the effort by promulgating public endorsements, media coverage, supportive evidence, regulations, legislation, and discrediting of detractors.

In government, CTFK and its partners engage in lobbying, like most other advocacy organizations, but CTFK’s strategy for influencing tobacco policy really hinges on establishing itself as an indispensable resource for regulators and lawmakers. For example, the CTFK plan lists myriad examples of support it has provided to government entities, such as assisting in lawsuits against the tobacco industry in Brazil, Peru, Uruguay, Uganda, Nigeria, and Kenya. In Panama, it notes “collaboration with the Ministry of Health of Panama who is interested in financing a regional effort” for tobacco litigation.[3]

Other government functions that CTFK apparently funds or assists include training staff, organizing meetings, and producing research or communications materials. For example, in Indonesia, CTFK worked with the Ministry of Home Affairs and the Ministry of Health to organize and fund “legal drafting workshops” for parliamentary counsel to encourage those lawyers to “report developments with the bad legislation and assist advancing tobacco control legislation.”[4] Similar efforts also seem to be under way in Uruguay, where CTFK refers to “coordinating a lawyers training, in collaboration with the Uruguayan Government,”[5] as well as in Nigeria and Uganda, where “the Campaign’s legal team has been working closely with in-country lawyers to draft regulations.”[6]

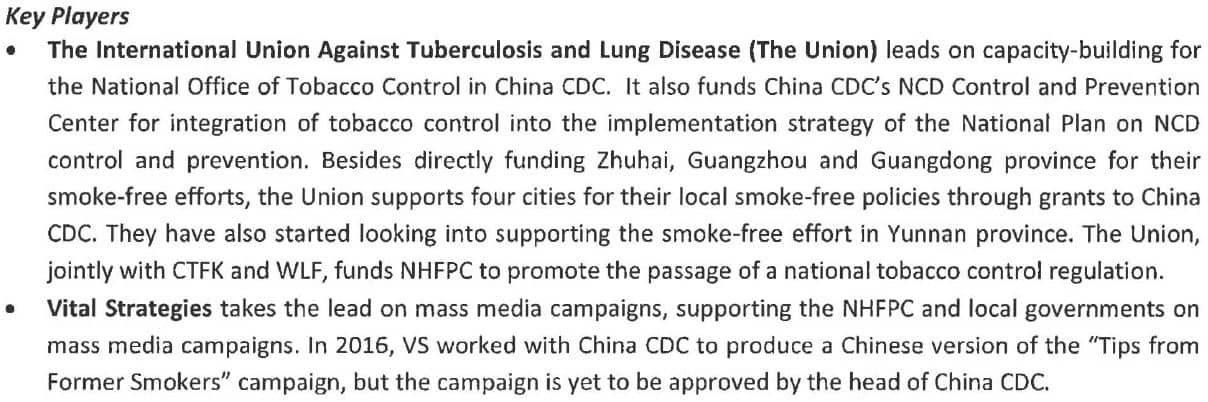

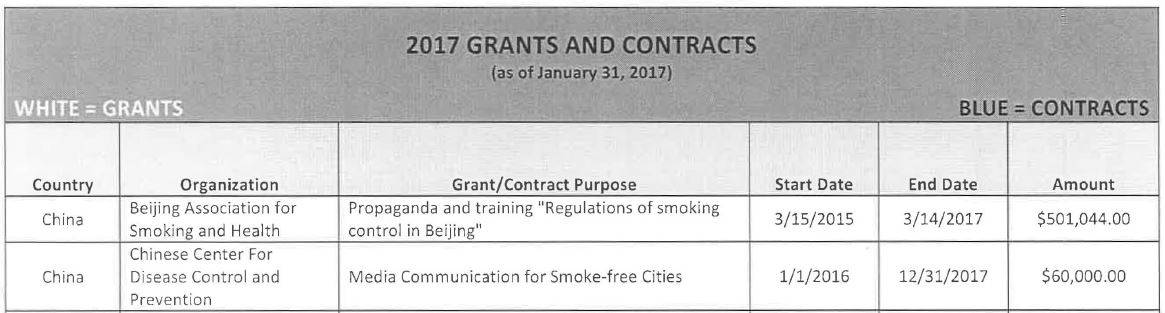

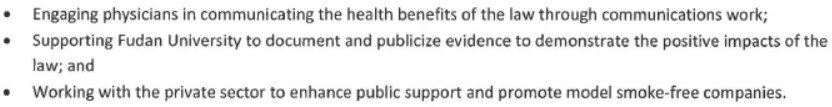

In some cases, the assistance CTFK and its partners provide to government is even more direct, such as in China, where it apparently has been funding the governments of three provinces (Zhuhai, Guangzhou, and Guangdong), four city governments, and the National Health and Family Planning Commission (a cabinet-level government agency until it was dissolved) to advance indoor smoking bans and “promote the passage of national tobacco control regulation.” CTFK’s partners, such as Bloomberg grantee Vital Strategies, have also been working with local governments and the Chinese CDC (which has received direct grants from Bloomberg and $60,000 from CTFK for “media communications”).[7]

In Brazil, CTFK notes that it provided the Solicitor General’s Office with “financial support as requested” to further its litigation agenda.[8]

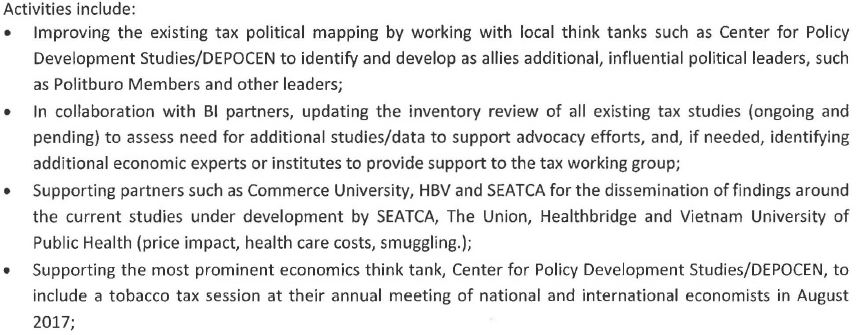

In Vietnam, CTFK reveals that along with the Union and Bloomberg, it financed the Steering Committee on Smoking and Health (also known as the Vietnam Tobacco Control Fund and formerly VINACOSH), as well as the Tax Policy Department in the Ministry of Finance.[9]

Notably, the plan led to a recent scandal over foreign political meddling in Mexico, where it was found that CTFK lawyers had fully written proposed legislation to ban e-cigarettes. That was not an isolated incident. Rather, it seems to be standard operating procedure for CTFK and its grantees to draft legislation for sympathetic lawmakers to then introduce. Other examples of CTFK’s activities around the world include the following:

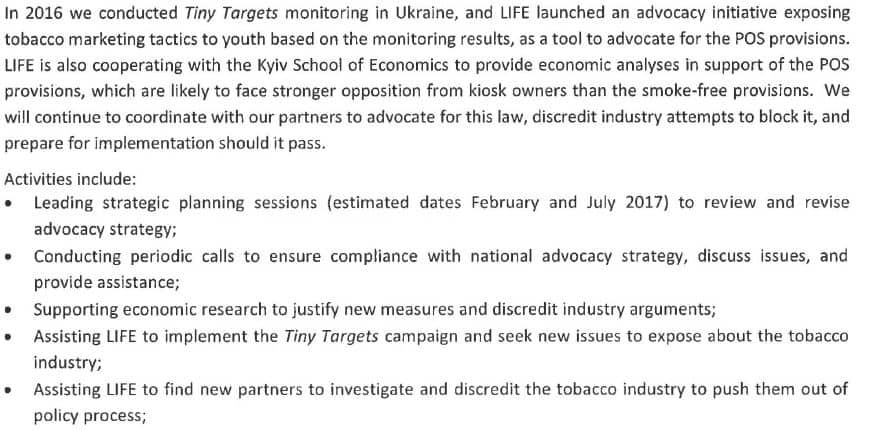

- CTFK notes that in 2015 one of its Ukraine grantees, LIFE Regional Advocacy Center (LIFE), “introduced bill 2820 through MP allies in Parliament” and describes plans to “work on a new bill” should that measure fail.[10]

- In Bosnia, CTFK boasts that the Minister of Health approved a bill “drafted by grantee PROI [Progressive Reinforcement of Organizations and Individuals] with assistance from CTFK.”[11]

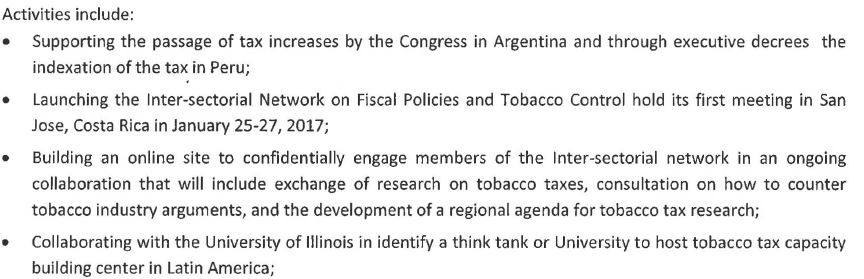

- In Latin America, CTFK’s activities included “drafting legal arguments and legislative proposals for target countries to authorize bans or restrictive regulations of these [flavored tobacco] products and support lobbying efforts.”[12]

- In the Philippines, it describes efforts “to file and push a smoke-free bill” aimed at blocking tobacco industry representatives from being part of the policy process, further noting that such a bill “has been drafted and will be filed as soon as the opportunity is ripe.”[13]

- In Africa, it notes that “through CTFK’s continued support, Ethiopia has drafted and advocated for the passage of [tobacco control laws] which should be presented to Parliament by February 2017.”[14]

When CTFK isn’t working directly with state actors to advance its agenda, its network partners are busy laying the groundwork to do so in the future. In addition to more pedestrian media tactics like press releases and publicity stunts (in Latin America they planned a “fake product launch, Killer Candy calendar, [and] candlelight vigil”),[15] they also cultivate relationships with research groups and universities to produce evidence of how beneficial CTFK’s plan will be for their respective countries.[16]

In China, Fudan University has received hundreds of thousands of dollars from CTFK to, among other things, “document and publicize evidence to demonstrate the positive impacts of the [smoke-free] law”—not investigate if it has positive impacts, but state that it does. It also received funds for the “advancement and evaluation of the smoking control legislation in Shanghai” and for “Building Capacity for Advocacy and Leadership in Tobacco Control at Chinese Universities.” [17]

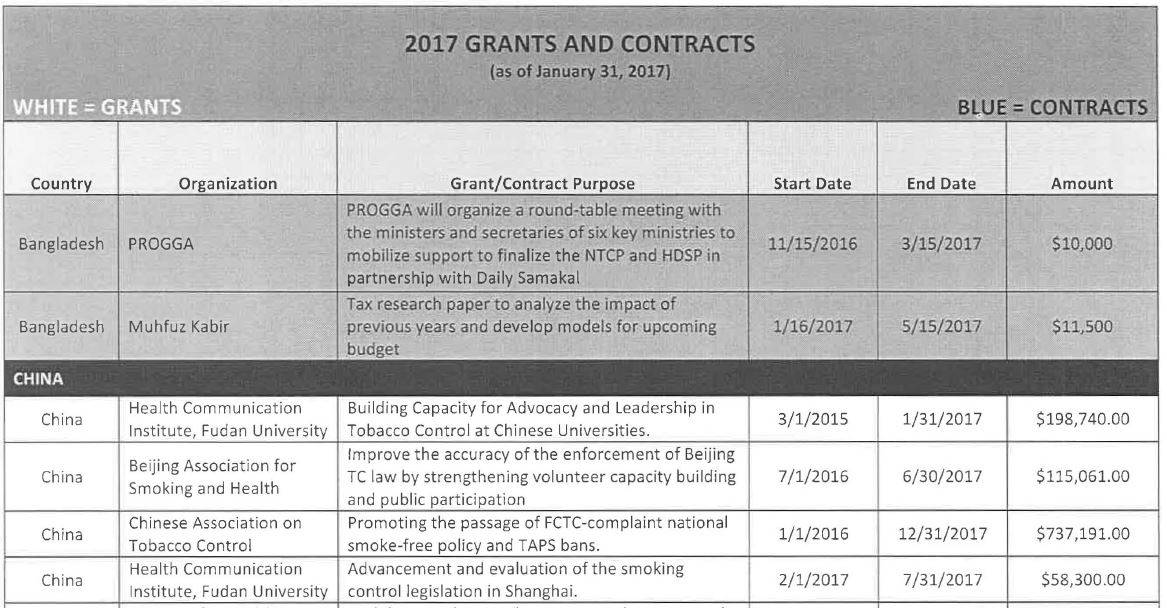

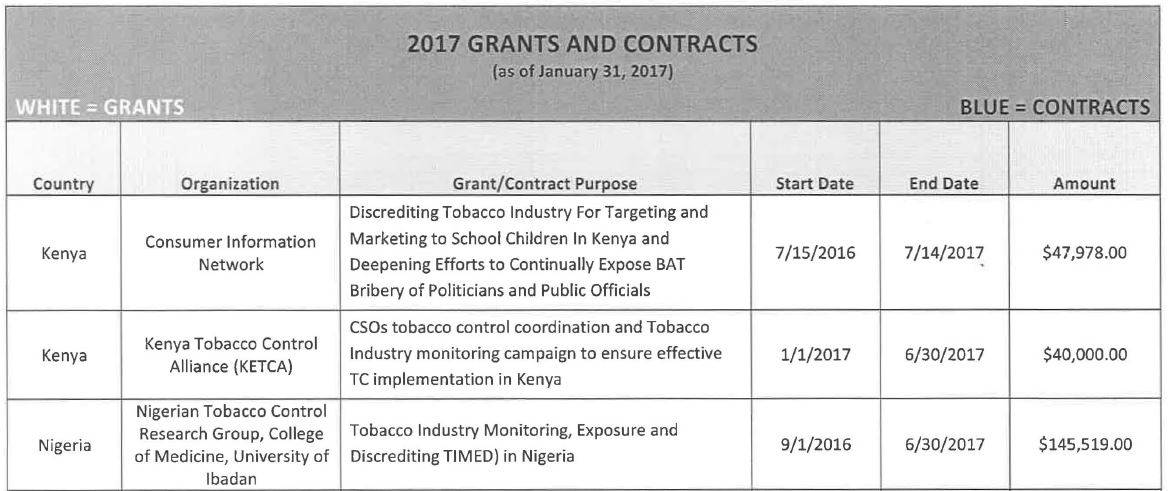

The National Law School of India University received over $70,000 for a similar advocacy-capacity building project, with recipients including “members of the Health and Police departments, law teachers and Judges on sensitizing to reduce tobacco use.”[18] In Nigeria, the University of Ibadan received about $145,000 for “Tobacco Industry Monitoring, Exposure, and Discrediting.”[19] And CTFK provided support to the Vietnam University of Commerce “for the dissemination of findings around the current studies under development” by other Bloomberg-funded outfits.[20]

In Ukraine, CTFK worked to support “economic research to justify new measures and discredit industry arguments,” while its grantee, LIFE, reportedly worked with the Kyiv School of Economics to “provide economic analyses in support of [bans on point of sale advertising] provisions.” LIFE also received assistance to find partners to help them “discredit the tobacco industry to push them out of the policy process.”[21]

U.S.-based universities also work closely with CTFK and receive financial support, including the University of Illinois[22] and Johns Hopkins University. CTFK credits the latter with publishing a report titled Tiny Targets that “aims to discredit the tobacco industry in Peru, Argentina, Bolivia, and Nicaragua.”[23]

If you think in-country journalists might question this potential interference in their democratic process, CTFK has a plan for that, too. Along with constructing the evidence and building a chorus of credible voices in support, CTFK’s plan involves partnering with local media outlets and training journalists to make sure the public—and especially lawmakers—hear what CTFK wants and ignore any contradictory messages.

Throughout its plan, CTFK refers to cultivating positive media coverage through training, workshops, and fellowships for journalists. In Bangladesh, for example, it notes that its partner PROGGA, an anti-tobacco advocacy group, has “trained 350 print, broadcast or online media journalists across the country and supports the Anti-Tobacco Media Alliance (ATMA).” CTFK boasts that journalists trained by PROGGA “have successfully generated much of the increased media coverage [on tobacco control.]” [24] According to the documents, PROGGA has been “working through the journalists to discredit the tobacco industry on a consistent basis,” while ATMA journalists have aided in the effort to “pressure the Government to adopt national tobacco control policy.”[25]

In some cases, CTFK and its grantees outright pay to manipulate news coverage. In Indonesia, it refers to “contracting with radio network KBR to develop and broadcast a series of programs” on tobacco use.[26]

In China, it lists “contractual partnerships” with Caixin Magazine and Xinhua News Agency—the state-run press agency. While noting that the Communist Party has recently curtailed the ability of foreign entities to directly contract with media outlets in China, CTFK boasts that it has been able to continue “effective media advocacy” through local partners.[27]

And this strategy doesn’t seem to be limited to LMICs. Just this week it was revealed that The Investigative Desk, a European news outlet, received an undisclosed sum for a contract with the University of Bath to publish anti-tobacco news stories. The contract was, in turn, funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies, which gave the University of Bath at least $20 million for its anti-tobacco work. The contract contains a provision compelling The Investigative Desk not to reveal that Bloomberg Philanthropies directly funds its activities.

Conclusion

Taken individually, the activities noted in CTFK’s strategy may not seem particularly problematic. Plenty of other advocacy organizations engage in this sort of coalition-building, communications marketing, and legislator outreach. Furthermore, its intentions sound well-meaning, portrayed as an effort to encourage the adoption of regulations that protect people from the harms of smoking.

Viewed as a whole, however, the strategy of CTFK and the wider Bloomberg-funded anti-tobacco effort appears aimed at winning policy battles and passing laws with little consideration of whether they result in actual reductions in smoking or improvements in health.

In Turkey, a country cited as a success story for implementing all of the WHO’s tobacco policies, which CTFK advocates for around the world, adult smoking rates actually increased from 27 percent to over 31 percent between 2012 and 2018. In the Philippines, under the iron fist of anti-drug zealot Rodrigo Duterte (whom the CTFK strategy credits for his “progressive policies on tobacco control”), the anti-smoking policies advocated by groups like CTFK have led to thousands of people being arrested, fined, or imprisoned.[28]

Even among higher-income populations, the policies favored by CTFK and the tobacco control authorities they support often backfire. High taxes increase tobacco smuggling and drive consumers toward the illicit market. Bans lead consumers to change behavior in ways not always beneficial to health. For example, recent research found that youth smoking substantially increased after San Francisco banned flavored tobacco products, including e-cigarettes.

On the other hand, there is evidence that alternative approaches work better for certain populations. These are vehemently rejected by the Bloomberg-funded anti-tobacco movement, who consistently ignore the successes of countries like Japan, where cigarette sales have dropped over 40 percent thanks to people switching to heat-not-burn tobacco products, and Sweden, which enjoys the lowest rates of smoking and lung cancer in the European Union as a result of its embrace of the use of non-combustible snus.

Despite all this, CTFK and its allies in the global tobacco control movement continue to advocate for policies that have been shown to consistently backfire, without any apparent effort to course correct. More troublingly, perhaps, they also appear uninterested in how their approach to influencing LMICs may be harmful to the long-term welfare of the people who live there. Despite claims to the contrary, the Bloomberg-CTFK strategy doesn’t seem focused on “supporting” existing political processes in these countries, but in commandeering them, creating a widespread system of dependency on foreign authorities—and with little regard for those authorities’ respect for democratic norms. The strategy may be effective for manipulating LMICs into adopting the tobacco policies Bloomberg and CTFK favor, but it may also be perpetuating or exacerbating the legacy of colonialism in the developing world.

[2]

[5]

[7]

…

…

[9]

[11]

…

![]()

[14]

[15] See endnote 12

[16]

[17]

…

[18]

[19]

[20]

[21]

[22]

[24]

…

[26]