Fred Smith and the Hourglass of Market Evolution

Photo Credit: Getty

Our much–loved CEI founder Fred L. Smith Jr. would often insist that we not refer merely to antitrust or antitrust policy, but to call it antitrust regulation.

Conventional notice-and-comment regulations aren’t written for the trustbusters’ myriad antitrust forays, yet antitrust is one of the most invasive, all-encompassing regulatory interventions possible. Like most economic regulation, antitrust transfers wealth from Peter, Inc. to Paul, Inc.—and away from the buying public made to suffer and pay more on Paul’s behalf.

Yet another Wall Street Journal editorial today frets over “hundreds of millions of dollars in billing and career advancement for the antitrust bar,” yet says nothing that hasn’t been repeated thousands of times with respect to the naked opportunism and the revolving door between the antitrust bar, academia, and the Federal Trade Commission and Department of Justice. Things probably will change only when disbarment becomes the penalty for filing an antitrust suit.

Antitrust doesn’t merely needle the targeted firm of the moment; in churning fashion, antitrust changes the very structure of numerous economic sectors, creating a fictitious economy that doesn’t reflect consumer demands or needs. Sometimes I call it the Original Sin of the Administrative State, although to be fair to its apologists, there were plenty 19th Century regulatory predecessors.

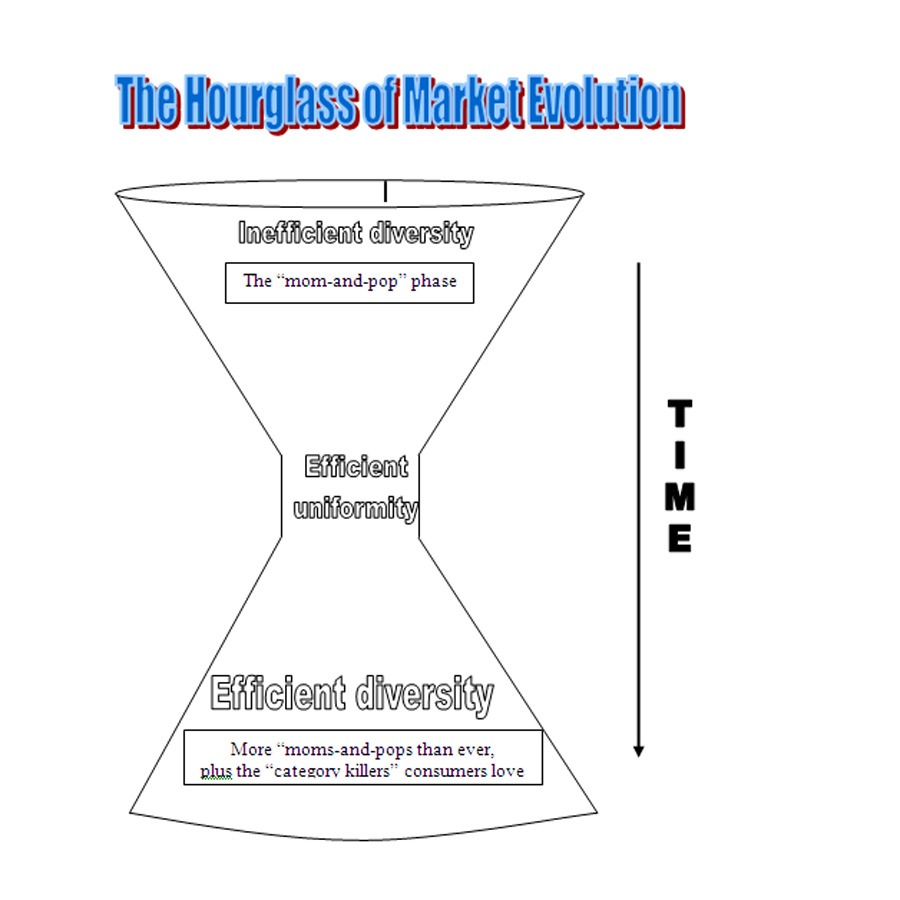

The recent spate of high-profile antitrust cases (against Google, Meta, Amazon, Microsoft, Live Nation, American Airlines/JetBlue and more) along with our reflecting upon Fred’s magnificent legacy have reminded me of the time when Fred, in a conversation at least 10 years ago, idly brought up the notion of an “Hourglass of Market Evolution” right off the top of his head.

Fred, who often made the case for abolishing antitrust rather than “reforming” it, casually described how he saw voluntary competitive markets evolving as society becomes wealthier. I was so thrown for a loop I scooted back to my office to draw what he had described verbally with pen and paper, and then used the illustrator tools in Microsoft Word to (very poorly) draw what you see here.

Granted, I should’ve reversed top and bottom; or even better, drawn it left to right and added “wealth” to that “time” axis; but what follows is the gist of Fred’s observation.

Fred remarked that when capitalism is new, and during a free economy’s early stages out of the agricultural (let’s say), folks may be making or growing their own necessities and luxuries, and trading with others in a state of “Inefficient Diversity,” or the mom-and-pop store phase. Then, when shareholder capitalism and “big business” takes root, that diversity might “go away,” (not really, of course) in favor of an “Efficient Uniformity” that nonetheless makes society and individuals richer with abundant oil and gas, grocery stores, mainframe computers and Fred’s Oreos.

Regulators, Fred warned, tend to intervene inappropriately against “trusts” in this vulnerable efficient uniformity phase (for example, the A&P or Microsoft “monopolies”). But when they do, they derail the higher-level economic expansion, job and wealth creation that emerge in the form of competitive responses.

But if that offending antitrust bar is kept at bay, the spread of wealth over time gives us not only those big-box stores and other dominant players, but it also allows for the flourishing of more mom-and-pops than ever. That is, we achieve an “Efficient Diversity” capable of placing large-scale inter-planetary entities alongside mass individualized customization up to and including the likes of household 3D printing and the Etsy painted-rock universes that coexist with Elon Musk.

Fred’s hourglass metaphor and with its North Star of protecting the emergence of efficient diversity is especially timely given inappropriate but rampant bipartisan calls for federal infrastructures ranging from tap water to space commercialization, in turn hobbling every smart city and energy/charging network innovation in between. Too often with these frontier sectors, as Fred would also say, “the government steers while the market merely rows.” That is genuine monopoly, and we don’t want it. The alternatives to Fred’s efficient diversity are problematic public/private partnerships being erected with little to no connection to markets or consumer choice, potentially sacrificing trillions in lost wealth.

Like no other, Fred would emphasize the importance of property rights in the creation and management of complex assets, as well as warn of the false distinction policymakers erect between the network grids and the goods and services flowing over them, and the need to allow freedom in both elements.

The hourglass is just one of Fred’s many lessons to us on the perils of politicized regulation rather than competitive discipline. The rent-seeking partnerships between business and government explain antitrust’s staying power. All such planning, thought, as Fred would put it, “drips with market socialism.”

The lesson of Fred’s hourglass for the liberty movement is to defend both the efficient uniformity and diversity categories. Efficient uniformity is most vulnerable to predation, yet it is a transitory phase necessary for efficient diversity and all the wealth and productivity those aspirations entail. Every antitrust case on tap looks ridiculous upon recognizing that the size and scope of private firms necessary to organize smart cities, to carry out manned missions to the Moon and Mars, and to undertake asteroid mining must be on a scale far larger than any enterprise that exists today. The only alternative is larger government monopoly power –that which antitrust is supposed to fight—to do these things, and for them to be done poorly if at all.

Fred Smith and the Hourglass of Market Evolution—it’s catchy, I think; someone with better chops than me should write a storybook about it, much like the classic illustrated antitrust-skeptic’s classic Tom Smith and his Incredible Bread Machine (“IBM,” get it?). As it happens, Fred and CEI reprinted that one back in 2006.

To the extent that antitrust regulation strikes down business practices that have misunderstood or ignored efficiency justifications, especially in an information-based economy on the verge of interplanetary travel and AI saturation, society and individuals are made poorer.

Antitrust, wrongly seen as being in the public interest, advances the wellbeing of various species of political predators. Targeted companies’ rivals have a direct financial interest in the outcome, and are protected from having to respond. Antitrust regulation decreases wealth and cracks Fred’s hourglass and scatters the sands of efficient diversity to the winds.