Politico’s failed critique of DOE’s climate science report – who’s misleading on hurricanes?

In September, Politico published an article titled “How a major DOE report hides the whole truth about climate change.” In October, I rebutted that article in a two–part essay. Today’s post provides further vindication of the Department of Energy (DOE) report, A Critical Review of Impacts of Greenhouse Gas Emissions on the U.S. Climate.

Background

Four reporters — Benjamin Storrow, Chelsea Harvey, Scott Waldman, and Paula Friedrich — co-authored the Politico article. Climate scientists John Christy, Judith Curry, Steve Koonin, Ross McKitrick, and Roy Spencer co-authored the DOE report.

In August, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed to repeal the Obama-era EPA’s 2009 Greenhouse Gas Endangerment Finding. That Finding supplied the foundational statutory and scientific rationales for the climate policy regulatory agendas of the Obama and Biden administrations.

The EPA’s repeal proposal includes a brief “climate science discussion” that frequently cites the DOE report. The Politico article aimed to undermine the case for Endangerment Finding repeal by discrediting the DOE report as a “political plan” rather than a “scientific exercise.”

Politico claims the DOE report “cherry-picks mainstream research and omits context,” “relies on outdated studies,” “cites analyses that were not peer reviewed,” and “revives debunked arguments.” As my rebuttal pieces show, Politico’s criticisms repeatedly misfire or backfire, and none comes close to refuting any of the DOE report’s conclusions. Today’s post further debunks the Politico reporters’ “omits context” allegation.

Update

The Politico article accuses the DOE authors of quoting selectively from the 2021 Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Specifically, the reporters fault the scientists for quoting one sentence about hurricane intensity in AR6 but not the next sentence. That omission is “clearly designed to mislead the audience,” the reporters contend. Not so.

Here is the AR6 sentence quoted by the DOE report:

There is low confidence in most reported long-term (multi-decadal to centennial) trends in tropical cyclone frequency- or intensity-based metrics due to changes in the best track data (AR6, p. 1585).

Here is the next sentence, which the DOE report did not quote:

This should not be interpreted as implying that no physical (real) trends exist, but rather as indicating that either the quality or the temporal length of the data is not adequate to provide robust trend detection statements, particularly in the presence of multi-decadal variability.

According to Politico, omitting “the very next sentence” is misleading because the sentence “specifically warns against making assumptions that no link exists between rising temperatures and stronger storms.” That criticism fails for several reasons.

First, the quoted sentence itself is not misleading. It neither states nor implies that there is no link between rising temperatures and stronger storms. Such a connection is inherently plausible because hurricanes are heat engines. However, whether a quantitative relationship between global warming and tropical cyclone behavior has been detected, and whether scientists should have low, medium, or high confidence in such detection, are chiefly empirical questions. The gist of the AR6 sentence quoted in the DOE report is that confidence is low due to data limitations.

Second, the next sentence in AR6 does not retract or modify the preceding sentence’s statement of low confidence. It just provides a bit more technical detail about the data limitations that impede “robust trend detection.”

Third, the so-called warning in the omitted sentence merely restates the old saw that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. It adds nothing to the discussion of confidence levels. Such admonitory language is gratuitous, important only to those who fear — or who aspire to be — the climate thought police.

Fourth, the next sentence of the DOE report quotes the following sentence from AR6: “It is likely that the global proportion of major (Category 3–5) tropical cyclone occurrence has increased over the last four decades…” (AR6, p. 132; DOE Report, p. 48). Let that sink in. The DOE report quotes AR6’s conclusion that a hurricane strength-warming link is “likely.” Thus, the DOE authors do not hide anything or mislead anyone.

It is the Politico reporters who mislead the public by omitting the DOE authors’ “very next sentence.” The reporters commit the journalistic malpractice they falsely ascribe to the DOE authors.

Fifth, empirical analysis posted this week by American Enterprise Institute scholar Roger Pielke, Jr. confirms the assessment of AR6 and the DOE authors that robust detection of a trend towards stronger hurricanes continues to elude scientists.

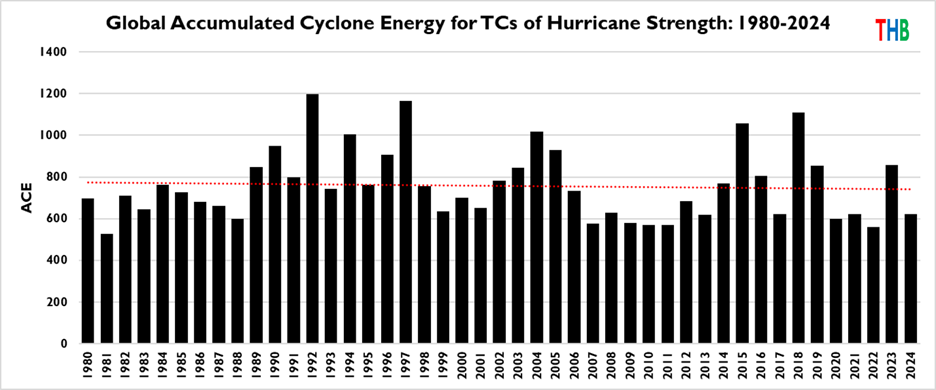

The chart below tracks annual changes in accumulated cyclone energy (ACE), a metric integrating hurricane intensity and duration, for global tropical cyclones of hurricane strength during 1980-2024. There is no trend.

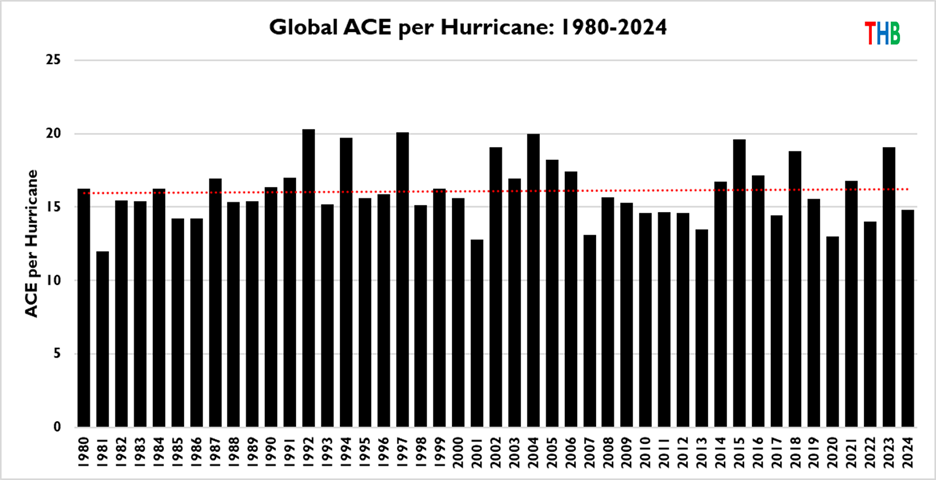

The next chart shows the global ACE per hurricane. There is also no trend.

Pielke, Jr. comments:

That lack of trend challenges a popular hypothesis—specifically, that changes in climate will result in fewer storms, but a greater proportion of them will be of higher intensities. As a matter of simple math, both fewer storms (the denominator in ACE/hurricane) and greater per-storm intensities (the numerator) should result in an increase in ACE per hurricane. While such a trend might emerge in the data in the future, to this point it has not.

The data depicted in the charts above should lower the already-low confidence in reported trends toward stronger hurricanes. Since the topic at hand is climate change, it goes without saying that a trend towards stronger storms could emerge in the future. To claim it is misleading not to belabor the obvious is itself misleading. It is also misleading to treat the absence of a trend towards stronger hurricanes, despite four decades of global warming, as a datum of no relevance to an Endangerment Finding.

What is even more misleading, though, is the Endangerment Finding’s reliance on overheated climate models, inflated emission scenarios, and lame adaptation assumptions — a recipe designed to exaggerate the physical effects of climate change and the socio-economic harmfulness of such effects. For further discussion of those topics, see part one and part two of “The Endangerment Finding’s disqualifying systemic biases.”