SAFE Rule Examined Part 4 Consumer Choice

Whenever someone asked vaudeville comedian Henny Youngman, “How’s your wife?” the King of the One Liners would reply: “Compared to what?” That joke pretty much sums up my view of the Trump administration’s Safer Affordable Fuel Efficient (SAFE) Vehicles Rule.

Whenever someone asked vaudeville comedian Henny Youngman, “How’s your wife?” the King of the One Liners would reply: “Compared to what?” That joke pretty much sums up my view of the Trump administration’s Safer Affordable Fuel Efficient (SAFE) Vehicles Rule.

Does the SAFE Rule restrict consumer choice? Yes, it does—compared to the Draft SAFE Rule’s proposal to freeze corporate average fuel economy (CAFE) standards at model year 2020 levels, the Competitive Enterprise Institute’s proposed rollback of CAFE standards to model year 2017 levels, and the legendary CAFE-Free Zone of ancient Libertaria.

However, compared to the 2012 Obama administration CAFE rule it repeals and replaces, the SAFE Rule is deregulatory and pro-choice. And pro-life, too, if, as advertised, easing the Obama-era CAFE standards will avoid thousands of fatalities and tens of thousands of serious injuries (85 FR 25034).

California and its allies, however, claim the SAFE Rule impairs consumer choice because its CAFE standards are too weak to ensure automakers produce “the fuel-efficient vehicles consumers want.” I respectfully disagree. Today’s post explains why the SAFE Rule is friendlier (or less hostile) to consumer choice than the 2012 Obama-era rule.

Quick Background

The SAFE Rule requires average fuel economy to increase by 1.5 percent annually, from 37 miles per gallon in 2020 to 40 mpg in 2026. The 2012 rule, if still in effect today, would require average fuel economy to increase by 5 percent annually, from 37 mpg in 2020 to 47 mpg in 2025 (85 FR 24259). The same agencies, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), authored both rules. Elections do have consequences! No Obama-era rule would call public attention to “the core philosophical question of the CAFE program—whether consumers should choose for themselves how much fuel economy they want, or whether the government should choose for them” (85 FR 25184-85).

More importantly, Part One of the SAFE Rule, entitled the One National Program Rule, finalized in September 2019, returns the California Air Resources Board, the most aggressive advocate of regulatory stringency, to its lawful pre-2009 role as a stakeholder, not a policy maker, in CAFE rulemakings. That institutional reform is a monumental deregulatory achievement. It should relieve much of the political pressure on the EPA, NHTSA, and the auto industry to ignore the adverse impacts of CAFE standards on vehicle affordability, consumer choice, and occupant safety.

The SAFE Rule and Choice

CAFE standards inherently restrict consumer choice, and the more stringent the standards, the more severe the constraints on what automakers may manufacture for sale. CAFE standards impair consumer choice the following ways:

- Manufacturers must spend hundreds of billions of dollars on technology to comply with CAFE standards. That increases the average cost of new motor vehicles, which in turn can price middle-income households out of the market for new cars.

- CAFE standards further increase average vehicle cost by cartelizing the auto industry. All automakers must comply. None is free to beat competitors on price by producing fleets with lower-than-average fuel economy.

- There are engineering tradeoffs between fuel efficiency and certain other vehicle attributes such as affordability, crashworthiness, roominess, ride height, and towing capacity. Because CAFE standards are to be set at the “maximum feasible” level in each model year, manufacturers are constrained from selling vehicles that maximize those other attributes, which some consumers value more highly.

- Regulatory agencies have different priorities than consumers. If that were not so, the invisible hand would achieve the same average fuel economy the agencies deem maximum feasible, and CAFE standards would not be “needed.” CAFE standards unavoidably shift capital and engineering talent from consumer priorities to bureaucratic priorities.

Because the SAFE Rule is deregulatory compared to the 2012 rule, automakers will have more freedom to produce and sell the mix of vehicles consumers want. In terms of the first bullet point above, the SAFE Rule will slow the rise in industry compliance costs, which in turn will slow the rise in retail sales prices (85 FR 24259). That will help middle -income households afford safer vehicles that get better mileage than the vehicles they currently own.

For example, the agencies estimate that for model year 2026, industry technology costs will be $19 billion or 57 percent lower than under the 2012 rule, average vehicle cost will be $1,450 or 4 percent lower, and vehicle sales will be 300,000 units or 2.2 percent higher (85 FR 24987). If replacing the 2012 rule with the SAFE Rule restricted consumer choice, vehicle sales would be lower, not higher, compared to the 2012 rule baseline.

As in previous posts in this series, I have not reanalyzed the agencies’ data and models and do not vouch for their accuracy. Nonetheless, the details should not change the basic conclusion. The linkages between fuel saving technology and vehicle cost, and between vehicle affordability and consumer choice, are not controversial.

SAFE Rule opponents claim, in various ways, that markets will fail to serve consumers unless the 2012 rule’s tough CAFE standards are retained. Those rationales do not withstand scrutiny.

Rationale 1: Automakers Are Dim or Lazy

The critics do not put it that way, but that is what their argument boils down to. Absent tough fuel economy standards, they contend, manufacturers will not produce the high-mpg vehicles “consumers want.” That makes little sense. Automakers are for-profit companies that compete for customers and shareholders in a global marketplace. To survive and thrive, they must produce vehicles consumers want. They spend tidy sums on consumer trends research. Automakers do not need bureaucrats bending their ears and twisting their arms to spot and pursue profitable opportunities.

The Trump agencies find no evidence that “vehicle manufacturers cannot identify—or can, but voluntarily forego—opportunities to increase sales and profits at the expense of their rivals by offering models that feature higher fuel economy.” Indeed, they explain, “behavior on the part of individual businesses that leaves obvious opportunities to increase profits unexploited by an entire industry seems extremely implausible, particularly in light of the fact that auto manufacturers are profit-seeking businesses whose ownership shares are publicly traded and subject to regular market valuation” (85 FR 24612).

Rationale 2: Consumers Will Be Forced to Spend More on Fuel

The SAFE Rule puts less pressure on manufacturers to sell high-mpg and electric powertrain vehicles, which consequently are expected to capture smaller market shares relative to the 2012 rule baseline (85 FR 25107). Some critics claim consumers will be harmed by any set of CAFE standards lower than the 2012 baseline standards because buyers will be “forced to spend more on fuel” (85 FR 24238).

That is nonsense. CAFE standards apply to vehicle fleets on average, not to individual vehicles. Lowering the standards just means more people will be able to afford a new car; it does not mean anyone will be forced to buy a car with a lower-mpg rating. Consumers who want and can afford to buy a strong hybrid, plug-in hybrid, or battery electric vehicle will still have a plethora of models to choose from. Manufacturers will be as free as ever to cater to such customers.

The agencies explain:

As Figure IV-6 shows, the range of fuel economies available in the new market is already sufficient to suit the needs of buyers who desire greater fuel economy rather than interior volume or some other attributes. Full size pickup trucks are now available with smaller turbocharged engines paired with 8 and 10-speed transmissions and some mild electrification. Buyers looking to transport a large family can choose to purchase a plug-in hybrid minivan. There were 57 electric models available in 2018, and hybrid powertrains are no longer limited to compact cars (as they once were). Buyers can choose hybrid SUVs with all-wheel and four-wheel drive. While these kinds of highly efficient options were largely absent from some body styles in MY 2008, this is no longer the case. (85 FR 24238)

But what if—as SAFE Rule opponents contend—the Trump agencies significantly underestimate consumer demand for high-mpg and electric vehicles? No problem! The profit-motive will spur some automakers to exploit that unmet demand, boosting their market share and profits. Those companies will also earn tradeable “overcompliance” credits worth $5.50 apiece for every tenth of a mile per gallon by which each vehicle manufactured for sale exceeds the automaker’s CAFE obligation (85 FR 24316, 23986). The invisible hand of competition will soon drive other firms to follow suit. As the agencies observe, entire industries do not leave “obvious opportunities to increase profits unexploited.”

Rationale 3: Fuel Costs Rise by More than Vehicle Costs Fall

Opponents claim the SAFE Rule is a bad bargain for consumers. They gleefully note that the estimated increase in fuel costs ($1,461) exceeds the estimated decrease in vehicle ownership costs ($1,428). However, that is comparing apples to oranges. The $1,428 in savings is realized over the first 5.6 years of ownership (85 FR 25176). The $1,461 increase in fuel costs is the cumulative impact absorbed by multiple owners over the assumed 39-year lifespans of the vehicles (85 FR 25110). Few buyers of a new vehicle will retain possession long enough to lose money on the deal. If the owner of a new car drives 14,000 miles per year, her annual gasoline consumption will increase by less than 40 gallons under the SAFE Rule compared to the 2012 rule (85 FR 25182).

Note, too, many consumers can more easily avoid higher fueling expenses than higher ownership costs. As the agencies explain, “significant increases in fixed upfront prices (which for many people translate to monthly financing costs) are harder for certain segments of new vehicle buyers to manage than fuel costs, which can be managed to some extent through vehicle switching or travel decisions” (85 FR 25178).

Rationale 4: Consumers Do Not Know What’s Good for Them

This line of criticism may be summarized as follows. Consumers have insufficient information about the benefits of fuel-saving technology. Consequently, they “undervalue” fuel economy improvements. Therefore, agencies should substitute regulatory directives for the signals the market fails to transmit to manufacturers.

The agencies’ response is persuasive. First, information is costly to produce and disseminate. Consumers rarely if ever know as much about a product as the people who make and sell it. Even if consumers know less than industry salespersons about potential fuel savings, that is not evidence of market failure (85 FR 24608).

Second, manufacturers have “consistently told” the agencies consumers are willing to purchase fuel saving technologies that repay the investment within two to three years. Thus, consumers do value fuel economy (85 FR 24606). Whether consumers should be satisfied with longer payback periods is not for policy makers to decide. Each consumer has her own financial priorities, transportation needs, and opportunity costs, all of which are unknown to central planners.

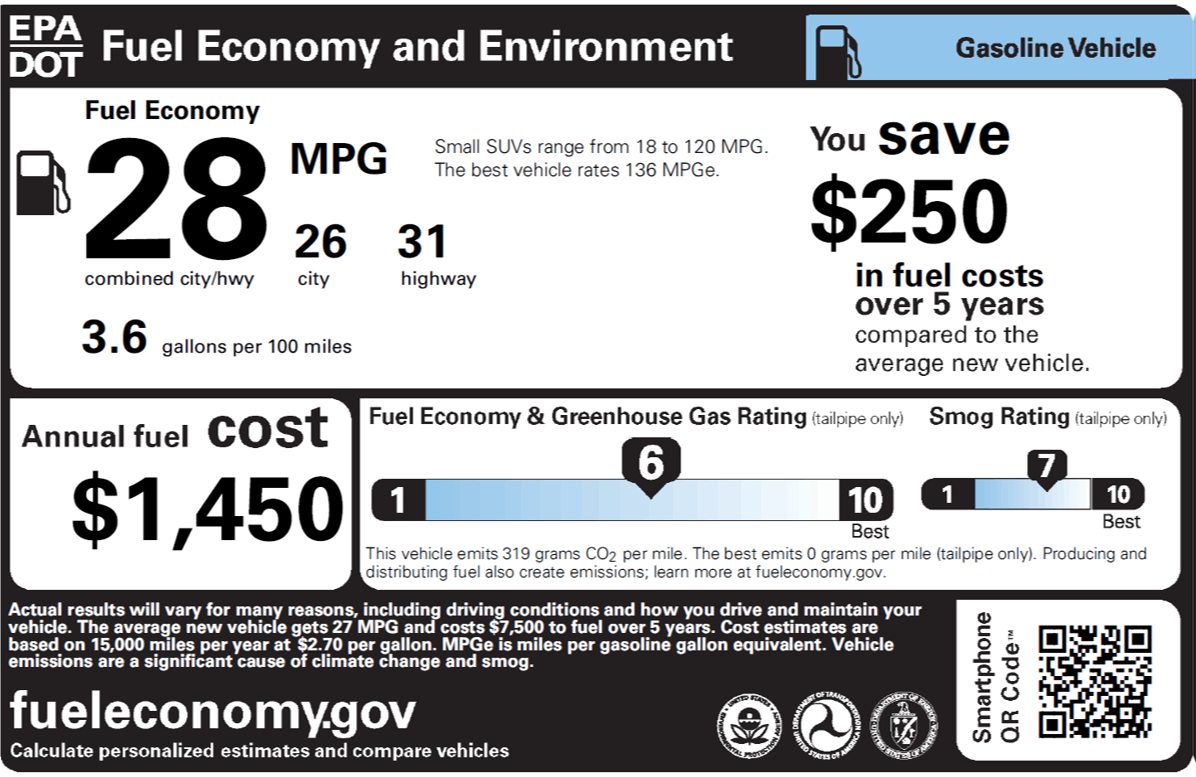

Third, consumers have a great deal of information about fuel economy. Manufacturers “have consistently advertised the fuel economy performance of their vehicles,” and federal law “requires the physical posting fuel economy performance, as well as estimated and comparative fuel cost information, on every new vehicle offered for sale” (85 FR 25116).

In addition, consumers are “reminded clearly and frequently of the financial consequences of their fuel economy choices each time they purchase fuel. Increasingly, consumers also have ready online access to comparisons of fuel prices at competing locations near their homes or along routes they travel” (85 FR 24610).

Rationale 5: Consumers Refuse to Act in Their Own Interest

Some SAFE Rule opponents claim tough CAFE standards are needed to cure a behavioral malady dubbed the “energy paradox.” The basic idea is that many “consumers voluntarily forego investments that conserve energy even when those initial outlays appear likely to repay themselves—in the form of savings in energy costs—over the relatively near term” (85 FR 24607).

During the Obama administration, the EPA and NHTSA tried but failed to find bona fide market failures that might explain the “energy paradox.” Most perplexing to them was the behavior of long-haul freight companies. The companies have abundant access to all kinds of technical information, and for many, fuel is the single biggest operating expense, exceeding drivers’ wages and benefits combined. Yet they were reluctant to spend an extra $10,000 or so apiece for new trucks with improved fuel saving technology. What market failure can explain such irrational behavior?

As my comment letter on the agencies’ 2015 (Phase 2) heavy truck rule explains, the EPA and NHTSA provided no solid evidence that truckers were underinvesting in fuel-saving technology. In fact, some of the agencies’ market failure hypotheses indicated truckers were simply being prudent buyers. The companies knew how much the agencies’ preferred technologies would cost, but only after years of road testing would anyone know whether the technologies worked as advertised or how the “improvements” might affect vehicle reliability and maintenance costs. The truckers, not the agencies, would be out of pocket if the new technology malfunctioned or failed to deliver the promised fuel savings bonanza. It is easy for bureaucrats with no skin in the game to scold private actors for not putting more of their capital at risk.

That was then. The SAFE Rule reports that “recent research cast [sic] doubt on whether such an energy paradox exists in the case of fuel economy” (85 FR 24607). The agencies comment that “conjectures about why buyers might undervalue potential savings from investing in higher-efficiency vehicle models do not represent evidence that they actually do so, and as discussed above, recent research seems to show that such behavior is not widespread, if it exists at all” (85 FR 24610).

Deregulatory Benefits

In the comment period, some commenters denied CAFE standards reduce R&D spending on other vehicle attributes such as occupant safety. The agencies’ rebuttal concludes with what may be the funniest line in the 1,105-page rule:

NHTSA believes that it is reasonable and appropriate to consider some aspects of safety as part of its consideration of economic practicability, because NHTSA continues to believe that vehicle manufacturers have finite budgets for R&D and production that may be spent on fuel economy improvements when they may otherwise be spent on safety improvements, among other things that consumer value. Some commenters said that that was not a reasonable assumption, but it is supported by statements from vehicle manufacturers, and NHTSA does not have a reason to disbelieve that companies have limited budgets. (85 FR 25136)

As mentioned earlier, easing CAFE standards will lower manufacturers’ technology costs. That will reduce vehicle costs and, thus, bring more new cars and light trucks within price ranges of middle-income households.

Alternatively, manufacturers can “redirect some or all of their savings in technology costs to instead improve other attributes of cars and light trucks—passenger comfort, safety, carrying and towing capacity, or performance—that potential buyers value” (85 FR 24702).

More than likely, they will offer “combinations of price reductions and more limited improvements in these other attributes on some of their models.” Easing CAFE standards will expand the range of strategies and combinations of strategies manufacturers can pursue to grow their profits and market share by selling cars consumers wants (85 FR 24702).

Conclusion

CAFE standards do not expand consumer choice, they restrict it. Because it is deregulatory, the SAFE Rule is less hostile to consumer choice than the 2012 rule it replaces. The agencies’ commentary on this point is suitable for framing:

CAFE does not affect fuel economy improvements that are supported by consumer demand—market forces will take care of that. Instead, it specifically addresses fuel economy improvements that are not preferred by consumers, and the agency sets standards that require manufacturers to make fuel economy improvements that consumers are not otherwise seeking. (85 FR 25181)