Science Reporters Get it Wrong: Moderate Alcohol Consumption Isn’t Dangerous

Joel Achenbach, a science and politics reporter, once asked why “many reasonable people doubt science.” He should look at his own reporting on alcohol research for the possible explanation. Despite decades of overwhelming evidence that moderate drinking confers health benefits, Achenbach’s August 3 Washington Post piece asserts that the evidence is “murky.” The basis for the assertion seems to come from a single study published in April in the journal The Lancet. Not only is a single study insufficient to challenge three decades of research, but Achenbach (along with reporters at other major news outlets) completely misunderstood the what this study found.

Conducted by long list of mostly European scientists, The Lancet study sought to determine what level of alcohol drinking maximized health benefits and minimized health risks by analyzing the health and dietary data of nearly 700,000 people. When the authors compared self-reported alcohol intake to health they found that the lowest risk of most heart-related illnesses and lowest incidence of death occurred among those consuming more than zero but less than 100 grams of alcohol (about 3.5 drinks) a week.

That finding prompted headlines like “One drink a day can shorten life” (from the BBC), “Even one drink a day linked to lower life expectancy” (CNN and Reuters), and the aforementioned Washington Post article, the headline of which read: “A huge clinical trial collapses, and research on alcohol remains befuddling.” It also prompted calls to lower the government guidelines which currently recommend people limit drinking to one serving a day, a suggestion made in the title of the study’s press release and for which the authors advocated throughout the paper.

But as pointed out by the likes of biostatistician Adam Jacobs and author Christopher Snowdon, the study actually confirms, not contradicts, the existing body of evidence which finds that moderate alcohol intake reduces both heart disease—the number one cause of death in the U.S.—and overall mortality risk. The only thing about this new study that is somewhat novel is in the way the results were spun.

NOT DRINKING HAS RISKS, TOO

The first of the graphs supplied in The Lancet paper shows a disturbing trend: as alcohol intake increases, so does all-cause mortality. But the data used to create that graph, like all the others in the main body of the paper, omits something very critical: data on the health effects of not drinking any alcohol.

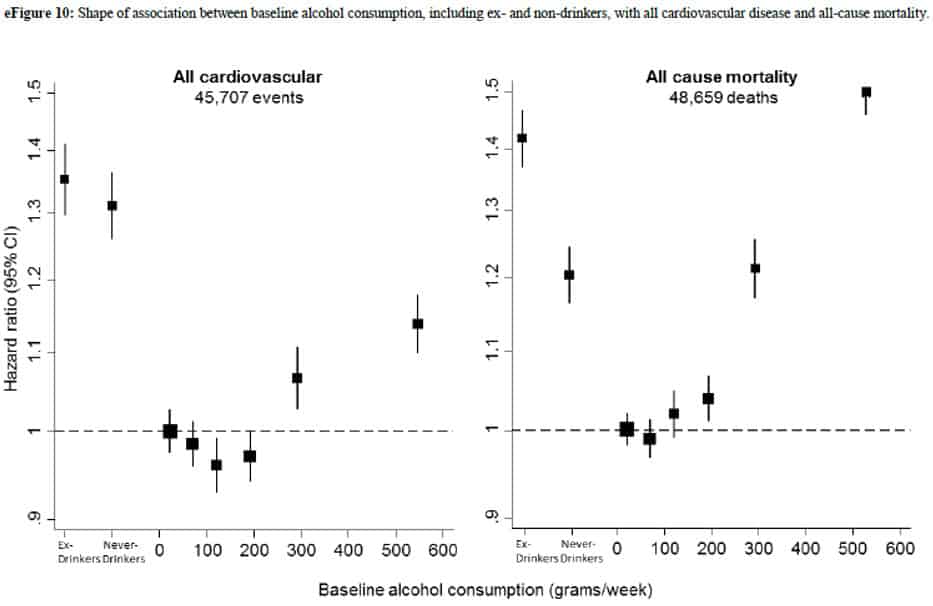

Once data from never-drinkers is included (which the study only does this in the appendix of the paper) we can see the results show what almost all studies looking at alcohol and heart health or death: the risks are highest among those who drink heavily and those who drink nothing with the best outcomes among those drinking a moderate level of alcohol.

The justification for excluding ex-drinkers is from their analysis is reasonable, because someone may quit drinking because of an illness that will also affect their overall health and risk of dying. In other words, comparing healthy drinkers to unhealthy abstainers could lead to the erroneous conclusion that drinkers have better health than abstainers because of their drinking when, in fact, it might be that the abstainers being studied have worse health due to unrelated conditions. This is known as “sick quitter bias,” and to reduce this bias it makes perfect sense to exclude ex-drinkers from the analysis, as much alcohol research does. However, it makes little sense to exclude never-drinkers from analysis as there’s no reason to believe these lifelong abstainers are likely to be sicker or lead unhealthier lives than those who drink.[2]

Luckily, the authors of the Lancet study divided the non-drinker category into both never-drinkers and quitters. When we look at drinkers compared only to never-drinkers, we see the authors found exactly what other research has: for most people, light and moderate drinking is associated with less risk of cardiovascular disease and death than those who don’t drink any alcohol. Even the heaviest drinkers, those consuming more than 35 drinks a week, were less likely to have cardiovascular disease than never drinkers. Never-drinkers had about the same mortality risk as those drinking about 21 alcoholic beverages a week and significantly higher risk than those consuming up to 14 drinks a week which, as it happens, is the limit currently recommended by the Centers for Disease Control.

INCREASED RISK DOES NOT MEAN UNSAFE

Despite their results showing that the current recommended limit on alcohol intake is optimal for health, the authors still insist it is evidence that the guidelines should be lowered. It does not. More importantly, the study in no way justifies the conclusion that greater-than-one drink a day reduces lifespan or that “alcohol is dangerous,” as one of the study’s authors has been repeatedly quoted.

Even taking looking only at the drinkers included in the study, it merely indicates that the optimal level of alcohol for the general public is around 100 grams, or seven drinks a week: drink more or drink less and risks increase. But what it doesn’t say is if these changes in risk are meaningful. We make choices every day that slightly increase or decrease our risks, but just because our behavior deviates from the optimal it does not mean the behavior is “unsafe.” For example, eating a slice of cake once a month probably slightly increases the risk of developing diabetes or obesity, but nobody would say such behavior is “dangerous.” This is an important distinction that almost every news story on this study ignored.

Christopher Snowdon sharply critiqued the conflation of risk and danger by noting that if we are going to change government alcohol guidelines based on a study finding that seven drinks a week is associated with the best health, then seven drinks a week should not only be the maximum limit, but also the minimum intake recommended (since the study found increased risk among never-drinkers.) “In other words, we should tell non-drinkers to start drinking and tell light drinkers to drink more,” and have headlines about how drinking no glasses of alcohol a day decreases life expectancy. Of course, such a message is unlikely to gain traction with most in the modern public health community and, certainly, not the authors of this particular study. [2]

After reading this study and its press release, it appears the authors involved are among those health activists hoping to discredit the decades of research showing health benefits from moderate drinking in order to convince the public and regulators that no level of alcohol intake is safe. That would explain why they highlighted the results that supported and ignored the results that contradicted that message. But it doesn’t explain why journalists writing stories on the study did the same thing.

A SCIENCE JOURNALISM ‘FAIL’

It’s difficult to fault journalists for occasional sloppy reporting. They are under enormous pressure to produce click-worthy content in a depressingly short amount of time. For science journalists, this often means relying on press releases for a quick and easy explanation of the study’s findings and useful quotes. In this case, neither the primary text of the study nor the press release, titled “Alcohol limits in many countries should be lowered, evidence suggests” mentioned the findings about the benefits of moderate drinking or the increased risk they found for never-drinkers, which as noted, were buried in the supplementary materials. Because of this, Snowdon writes that he is “inclined to give the Fourth Estate a break on this occasion.” I am not.

Lack the time or background to scrutinize a study from front to back, to understand its results, context, and implications is not an excuse. If that is the situation in which reporters find themselves they (and certainly the reading public) would be better served if they simply didn’t write about the study at all. While I can certainly sympathize with the demands that might lead a reporter to take shortcuts, the explanation that the slipshod reporting we’ve observed on The Lancet study was caused by reliance on a misleading press release, doesn’t absolve this this journalistic failure: if anything, it makes it more offensive.

If a pharmaceutical company issued a press release about how wonderful their new drug, failing to disclose the reported negative side effects, would we tolerate reporters uncritically echoing that narrative? Would we be satisfied if news coverage included only the facts and quotes pulled from the press release, information carefully curated to present the company and its product to the public in the best possible light? Of course not. Yet, when it comes to science journalism, this sort of press-release parroting is becoming common practice. Consequently, instead of the science news that provides readers insight into how the research on a topic is evolving, we get hyperventilating headlines that exaggerate, confuse, and misinform.

These science news stories, which too often contradict those of the previous day, affect how people see the world, live their lives, and the opinions they hold—even if the stories are later corrected. Corrections are boring, but headlines about your possible addiction to cheese stick in the mind. People who write press releases understand this: even if it is inaccurate, a press release with grandiose claims about a new study gets attention, both from journalists and the reading public.

Likely, most of the reporters spreading this sort of science spin aren’t unaware that that’s what they’re doing. But, the frightening possibility is that some do know and simply don’t care.

Perhaps then, the answer to Achenbach’s question about why reasonable people question scientifically accepted wisdom isn’t because they distrust science, but rather that they’ve grown skeptical of science reporting. With coverage like we’ve seen on The Lancet study, it is hard to argue that this is such an unreasonable position to take.

Notes:

[1] In the U.S. a standard drink contains about 14 grams of alcohol. This is roughly equivalent to a 12-ounce can of standard-strength beer, a 5-ounce serving of wine, or a shot of 80-proof spirits.

[2] Studies since the 1980s have accounted for sick quitters and continue to find that moderate drinkers have less risk of cardiovascular disease than non-drinkers. See e.g.

- Boffetta P, Garfinkel L. “Alcohol drinking and mortality among men enrolled in an American Cancer Society prospective study.”

- Marmot M, Brunner E, “Alcohol and cardiovascular disease: the status of the U shaped curve.”

- Fuller, TD “Moderate Alcohol Consumption and the Risk of Mortality.”

There is evidence that suggested reason light-to-moderate alcohol intake decreases cardiovascular risk is because of its “antiatherosclerotic” effect: it raises high-density lipoprotein (HDL, the “good fat”) and because of its anti-coagulant effect (similar to taking aspirin).

[3] As it shouldn’t. Certain individuals, for example alcoholics or those at high risk for liver disease, would certainly not be served by being told that they should have one alcoholic beverage a day because, for them, having one drink is not possible and likely would not reduce their health risk to a greater extent than it would increase their health risks