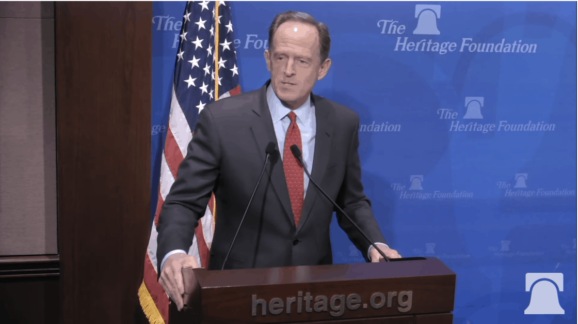

Sen. Toomey Defends Capitalism

Yesterday afternoon Sen. Pat Toomey (R-PA) gave an excellent and much-needed speech at the Heritage Foundation on capitalism and its right-leaning critics. Toomey maintained a reasonable and respectful manner, but made clear that he thinks that the anti-market measures promoted by self-described nationalists and populists are a mistake and would be a failure if enacted.

When it comes to proposals to restrict trade or for government to favor certain industries over others, we need to be clear about what problems such policies would ostensibly be solving. In certain cases, the supposed problems exist mostly in the minds of policy advocates. Take the claim that average wages for American workers have stagnated or declined in real terms over the last 40 years. That’s simply not true, especially so when one accounts accurately for the growth of both non-monetary benefits as well as wages and salaries.

In fact, far from being “left behind,” income for hourly wage workers has been growing fastest for those at the very bottom in the income ladder. And income growth has been faster in the last 20 years than in the previous 20—precisely the opposite of what most populists would have us believe. The excellent new book by the American Enterprise Institute’s Michael Strain, The American Dream Is Not Dead, makes this abundantly clear.

But even when there are real concerns to be dealt with, such as declining demand for manufacturing workers, the protectionism and favoritism of populist economic policy would not help and would, almost certainly, make the situation worse.

As Toomey points out, while we have far fewer Americans employed in the manufacturing sector as in previous generations, we have more manufacturing output—and a similar share of GDP derived from it—than at any point in our supposed historic heyday. Far from it being the case that “we don’t make anything in this country anymore,” if the U.S. manufacturing sector alone were its own country, it would rank among the world’s 10 biggest economies.

Those factory workers of yesterday aren’t simply sitting around unemployed. Many of those people who did, or otherwise would have, worked in manufacturing in previous decades are today working in the services sector—everything from doctors and lawyers to burrito artists and hair stylists.

As the White House keeps reminding us, we are currently seeing the lowest unemployment rates in half a century. Given that the shift in employment shares has been driven by competitive forces and have been consistent with rising standards of living, it’s not clear why the populists believe the federal government should try to artificially inflate the payrolls of manufacturing firms, other than in service of some kind of industrial nostalgia for muscle-intensive workplaces.

The biggest reason for this shift in the American workforce is that new technology and production methods have made every existing worker far more productive. Toomey cites figures from the Urban Institute, but this is a widely agreed upon phenomenon. Roughly 90 percent of the shift away from manufacturing employment is the result of automation and productivity gains with, at most, 10 percent due to increased competition from low-priced imports.

Higher tariffs on consumer goods from China and steel from Canada will not (thankfully) reverse these decades-old trends. In order to stay competitive, U.S. firms need to take advantage of every advance in cost-cutting and efficiency. A policy agenda that forces them to do the opposite would be a grave threat to everyone’s economic future.

That economic threat is ultimately Toomey’s most important point. Out of a misguided desire to solve perceived social problems with government economic policy, populists are suggesting an extremely risky solution: implement policies that even their advocates agree would slow economic growth and possibly even shrink the economy, in hopes that that economic pain will somehow invigorate civil society and make families stronger.

It’s sort of a social conservative version of the environmental left’s “de-growth” theory. Not only is it not likely to actually solve the problems being targeted, it would leave everyone with fewer tools and resources for solving the problems that inevitably remain (to say nothing of the new, unplanned ones that such policies would create).

As Toomey put it, “economic growth doesn’t solve all problems, but it makes all problems easier to solve.”