Senate pulls plug on California’s gas car ban

Photo Credit: Getty

The US Senate on Thursday voted 51-46 for H.J. Res.88, a Congressional Review Act (CRA) resolution of disapproval to repeal the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) December 2024 approval of California’s Advanced Clean Cars II (ACC II). ACCII features the state’s zero emission vehicle (ZEV) mandates that ban sales of new gas- and diesel-powered cars and pickups. The Senate’s vote is wonderful news for automobile consumers, the US auto industry, and all liberty-loving Americans.

The House on May 1 voted 246-164 for the resolution. The measure now goes to President Donald Trump, who is expected to sign it into law. This sequence of events will accomplish a sea-change in US public policy.

Aided and abetted by the Obama and Biden administrations, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) was on its way to becoming the nation’s de facto Industrial Policy Czar for Climate and Cars. Moreover, California and its blue state allies were poised to exert cartel-like market power over the auto industry, increasing vehicle prices and decreasing consumer choices beyond their borders.

The CRA provides an expedited process for the House and Senate to overturn agency rules. Critically, CRA resolutions cannot be filibustered in the Senate, requiring only a simple majority of 51 votes for passage. The House and Senate vote on identical CRA resolutions, so there is no opportunity for a conference committee to dilute or weaken a resolution. Once an agency rule has been overturned by an enacted CRA resolution, the rule “may not be reissued in substantially the same form.” Nor can litigants rescue a CRA-repealed rule, because CRA resolutions are exempt from judicial review. In the words of those adorable Munchkins, a rule killed by the CRA is “really most sincerely dead.”

Over the past several weeks, Democratic leaders avoided debating the legal and policy arguments against California’s gas-car ban. Instead, they argued that the EPA’s waiver of Clean Air Act (CAA) preemption for the ACC II program is not a “rule” for CRA purposes. My colleague Daren Bakst succinctly explained the common sense of the matter in a recent coalition letter signed by 56 organizations:

The waivers are exactly the type of agency actions that Congress envisioned would be addressed under the CRA: generally applicable policies affecting the rights or obligations of non-agency parties. The waiver for the car ban, for example, will directly affect tens of millions of people and possibly the entire country. It is hard to imagine anything more generally applicable.

The remainder of this post delves into core legal issues Senate Democrats studiously avoided. Here is the big picture in a nutshell. The Obama and Biden administrations collaborated with the California Air Resources Board (CARB) to defy Congress’s express, broad, and categorical preemption of state laws or regulations “related to” to fuel economy standards. Thursday’s vote in the Senate positions President Trump to terminate that mischief.

ACC II: Unlawful under the nation’s fuel economy statute

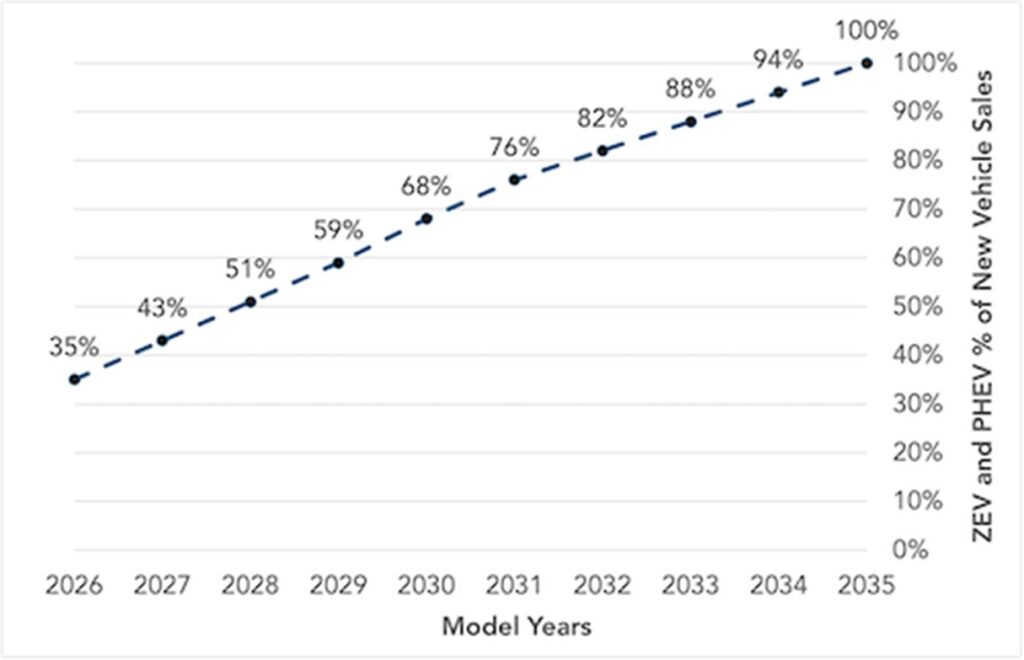

Unlike the first Advanced Clean Car (ACC) program, for which the EPA granted waivers in 2013 and 2022, ACC II does not include any new tailpipe carbon dioxide (CO2) emission standards for combustion engine vehicles. Although such tailpipe standards exert upward pressure on vehicle prices, the major threat to vehicle affordability, automotive choice, and auto industry viability comes from the ZEV mandates. The original ACC required that about 15 percent of new passenger cars and pickups in California be electric vehicles (EVs) by 2025 (78 FR 2112, 2114). ACC II requires all sales of new light duty vehicle sales in the state to be EVs by 2035.

As explained in painstaking detail by the Trump administration’s September 2019 One Program Rule, also known as Part I of the Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient Vehicles Rule (SAFE 1), California’s tailpipe CO2 emission standards and ZEV mandates are preempted by Section 32919(a) of the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA), the nation’s fuel economy statute.

EPCA Section 32919(a) states:

When an average fuel economy standard prescribed under this chapter is in effect, a State or a political subdivision of a State may not adopt or enforce a law or regulation related to fuel economy standards or average fuel economy standards for automobiles covered by an average fuel economy standard under this chapter.

EPCA preemption is clear, sweeping, and categorical. The preemption is expressly stated. It applies to state policies merely “related to” fuel economy standards. It allows no exceptions, not even for state regulations identical to federal fuel economy standards. Moreover, neither NHTSA nor any other agency may waive EPCA preemption. Thus, EPCA 32919(a) is not a “general rule of preemption” requiring subsequent regulatory adjudication to fine tune the boundaries of permissible state action. It is absolute and definitive (83 FR 42986, 43233).

Federal preemption statutes derive their authority from the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution (Article VI, Clause 2), which states:

This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.

As the Supreme Court explained in Maryland v. Louisiana (1981), “It is basic to this constitutional command that all conflicting state provisions be without effect.” That means any conflicting state policy is void ab initio—from the moment the policy is adopted or enacted, not when a court later declares it so (Ninth Circuit, Cabazon Band of Mission Ind. v. City of Indio (1982)).

Tailpipe CO2 standards are directly (i.e., physically and mathematically) “related to” fuel economy standards. An automobile’s CO2 emissions per mile are directly proportional to its fuel consumption per mile. Consequently, tailpipe standards calibrated in grams CO2 per mile convert mathematically into Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards calibrated in miles per gallon. If an agency regulates tailpipe CO2 emissions, it also regulates fuel economy, and vice versa (84 FR 51310, 51313). That is because tailpipe CO2 emissions and fuel economy are “two sides (or, arguably, the same side) of the same coin” (83 FR 42986, 44327).

It was only because of such mathematical convertibility that the Obama administration EPA and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) could boast, in their May 2010 joint rule establishing tailpipe CO2 and CAFE standards for model year 2012-2016 light-duty vehicles, that they had achieved a “harmonized and consistent National Program.”

The EPA and NHTSA concisely explained the “very direct and close” relationship (75 FR 25324, 25327) between their respective standards:

The National Program is both needed and possible because the relationship between improving fuel economy and reducing CO2 tailpipe emissions is a very direct and close one. The amount of those CO2 emissions is essentially constant per gallon combusted of a given type of fuel. Thus, the more fuel-efficient a vehicle is, the less fuel it burns to travel a given distance. The less fuel it burns, the less CO2 it emits in traveling that distance. While there are emission control technologies that reduce the pollutants (e.g., carbon monoxide) produced by imperfect combustion of fuel by capturing or converting them to other compounds, there is no such technology for CO2. Further, while some of those pollutants can also be reduced by achieving a more complete combustion of fuel, doing so only increases the tailpipe emissions of CO2. Thus, there is a single pool of technologies for addressing these twin problems, i.e., those that reduce fuel consumption and thereby reduce CO2 emissions as well (emphases added).

The two types of standards will remain mathematically convertible as long as affordable and practical onboard carbon capture technologies do not exist (71 FR 17566,17670). Since the start of the CAFE program in 1975 and for the foreseeable future, all design and technology options for reducing tailpipe CO2 emissions from combustion-engine vehicles, such as aerodynamic streamlining, low rolling resistance tires, and hybridization, are fuel-saving strategies by another name.

The Congress that enacted EPCA in 1975 understood the scientific relationship between CO2 emissions and fuel economy. That is why it approved the EPA’s procedure of testing automotive fuel economy by measuring tailpipe emissions of carbon-based compounds, chiefly CO2 (EPCA Section 503(d)(1)).

While ZEV mandates do not have a direct (one-to-one) relationship to fuel economy standards, they are nonetheless substantially related. Fuel economy standards are fleet-average standards. During the first 21 years of the California ZEV program (1990-2011), ZEV market share in California remained under 1 percent of new vehicle sales, so had negligible impacts on fleet-average fuel economy.

However, as ZEV mandates tighten, fleet-average fuel consumption per mile decreases, and fleet-average fuel economy increases. Conversely, when fuel economy standards (or their CO2-tailpipe equivalents) reach a certain stringency, automakers cannot comply without selling more EVs and fewer combustion engine vehicles. For example, the stringent implicit fuel economy standards in the EPA’s April 2024 vehicle emissions rule are projected to restrict non-electric vehicle sales to less than one-third of the new car market by 2032 (89 FR 27842-27856). Because ZEV mandates are substantially related to fuel economy standards, EPCA also expressly preempts state ZEV programs.

Furthermore, EPCA impliedly preempts state policies regulating or prohibiting tailpipe CO2 emissions because such policies interfere with the CAFE program in three main ways.

First, California’s policies revise regulatory determinations Congress authorized NHTSA to make. EPCA expressly requires NHTSA to weigh and balance four factors when determining CAFE standards: technological feasibility, economic practicability, the effect of other federal emission standards on fuel economy, and the national need to conserve energy (49 U.S. Code § 32902). EPCA, as interpreted by DC Circuit case law, also directs NHTSA to consider the impact of fuel economy standards on occupant safety (CEI v. NHTSA, 1992). California is not bound by those factors and is free to subordinate them to climate ambition.

Only by sheer improbable accident would CARB, when prescribing tailpipe CO2 standards, balance such factors the same way NHTSA does when prescribing fuel economy standards. Indeed, there is no policy rationale for elevating CARB from fuel economy stakeholder to decisionmaker unless its technical assessments and regulatory priorities differ from NHTSA’s. As environmental attorney Marc Marie observes, when Congress directs an agency to balance specific decision criteria, state regulations that disturb that balance are impliedly preempted (Arizona v. United States, 567 U.S. 387, 405 (2012)).

Second, California’s ZEV mandates conflict with the structure of the CAFE program. ZEV standards are technology-prescriptive, requiring automakers to sell increasing percentages of vehicles powered by batteries or fuel cells. CAFE standards are technology neutral. As the Obama administration EPA explained, under the CAFE program, manufacturers are “not compelled to build vehicles of any particular size or type.” Rather, each manufacturer has its own fleet-wide performance standard that “reflects the vehicles it chooses to produce.”

Third, EPCA as amended prohibits NHTSA from considering the fuel economy of alternative vehicles (49 U.S. Code § 32902), including EVs (49 U.S. Code § 32901), when setting CAFE standards. The amendment aims to ensure that CAFE standards never become so stringent manufacturers must sell EVs to comply (85 FR 24174, 25170). Mandating EV sales is the very purpose of the ZEV program, which logically culminates in banning combustion engine vehicles.

In short, California’s tailpipe CO2 standards and ZEV mandates are both expressly preempted by EPCA 32919(a) and impliedly preempted by their inherent conflicts with the statutory fuel economy program Congress established. Preemption statutes operate ab initio, which means EPCA voided California’s tailpipe CO2 standards and ZEV mandates years before the EPA agreed to review them. EPCA automatically turned those policies into legal phantoms—mere proposals without force or effect.

Fruit of a poisoned tree

Readers may wonder how CARB came to wield regulatory powers denied to it by Congress’s clear, broad, categorical preemption. The answer is a series of underhanded moves by the Obama and Biden administrations.

It all started in 2009, when EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson agreed to reconsider her predecessor Stephen Johnson’s denial of California’s request for a waiver to enforce CARB’s tailpipe CO2 standards of new cars and pickups, adopted pursuant to the state’s greenhouse gas motor vehicle statute, AB 1493. Jackson’s reconsideration raised the fearsome prospect of a patchwork-quilt of market-balkanizing fuel economy requirements. Why so?

As noted, tailpipe CO2 standards are implicit fleet-average fuel economy standards, and under CAA Section 177, other states can opt into vehicle emission standards “identical” to those for which the EPA has granted a waiver under CAA Section 209(b). Each automaker typically sells a different mix of vehicles in each state because consumer preferences differ from state to state. Thus, to achieve the same average tailpipe CO2 emissions in two different states, automakers would have to reshuffle the mix of vehicles delivered for sale in those states. If all states were to adopt California’s standards, each automaker would potentially have to manage 50 separate fuel economy fleets—an extreme version of the market fragmentation Congress enacted EPCA 32919(a) to prevent.

Note, too, that the Obama administration confronted manufacturers with the patchwork peril during the Great Recession, when GM, Ford, and Chrysler tottered on the brink of bankruptcy. Then, in a maneuver resembling a protection racket, the administration made the industry an offer it could not refuse.

In closed-door, “put nothing in writing, ever” negotiations run by Obama climate czar Carol Browner, California and its state allies agreed to deem compliance with EPA’s forthcoming model year 2012-2016 tailpipe CO2 standards as compliance with their own. However, manufacturers, for their part, would have to pledge their support for the new “national” program administered by the EPA, NHTSA, and CARB. That included surrendering their due process rights under EPCA.

As memorialized in the same May 2010 joint rule acknowledging the “very direct and close” relationship between CAFE and tailpipe CO2 standards, automakers’ obligations included “not contesting the final GHG and CAFE standards for MYs 2012–2016, not contesting any grant of a waiver of preemption under the CAA for California’s GHG standards for certain model years, and to stay and then dismiss all pending litigation challenging California’s regulation of GHG emissions, including litigation concerning preemption under EPCA of California’s and other states’ GHG standards” (75 FR 25324, 25328 emphasis added).

For all we know, Browner also conditioned the availability of bailout money on automakers’ fealty to the so-called national program. As a House Government Oversight Committee report observed, “The negotiations on the 2009 auto industry bailout occurred simultaneously with the negotiations on the Model Year (MY) 2012 to 2016 fuel economy standards.”

However, EPCA 32919(a) was still in force. How then did NHTSA square California’s new role as de facto fuel economy regulator with EPCA preemption? About midway through the 405-page rule, we find this evasive answer: “NHTSA is deferring further consideration of the preemption issue” (75 FR 25324, 25546).

Two years later, in the Obama administration’s 2012 joint rule establishing CO2/fuel economy standards for model year 2017-2025 light duty vehicles, NHTSA again announced it was “deferring consideration of the preemption issue” (77 FR 62624, 63147). NHTSA did not stop deferring until the Trump administration proposed the SAFE Rule in August 2018.

In both the 2010 and 2012 vehicle rules, NHTSA’s excuse for “deferring” was that “it is unnecessary to address the issue further at this time because of the consistent and coordinated Federal standards that will apply nationally under the National Program.”

But then, five years later, the Obama administration tossed consistency out the window. The 2012 rule required the agencies to conduct mid-term evaluations (MTEs) of their respective standards for model years 2022-2025 light duty vehicles. The MTEs were to be completed “concurrently” “in order to align the agencies proceedings’ for MYs 2022-2025 and to maintain a joint national program” (77 FR 62624, 62784). The plan, posted on NHTSA’s Website, was for the EPA to publish its draft MTE in mid-summer 2017 and finalize it by the April 1, 2018 deadline specified in the rule.

However, when Trump won the November 2016 election, the EPA rushed out a proposed MTE on November 30, and then finalized it in January 2017, just in time to confront the incoming Trump administration with a regulatory fait accompli. This precluded meaningful coordination with NHTSA, scuttling the “harmonized, consistent national program.”

The Trump administration’s April 2020 SAFE Rule put the band back together, promulgating coordinated and consistent tailpipe CO2 and CAFE standards for model year 2021-2026 light duty vehicles.

However, the Biden administration dismantled the revived national program by adopting EPA tailpipe CO2 standards for model year 2023-2026 light duty vehicles in December 2021 (86 FR 74434, 74493) and model year 2027-2032 LDVs in April 2024 (89 FR 27842, 27856) that “necessitate” ZEV sales. Those standards are increasingly inconsistent with NHTSA’s CAFE standards.

At the risk of belaboring the obvious, CARB’s ZEV mandates are manifestly not “harmonized, consistent, and coordinated with” NHTSA’s CAFE standards.

The point here is that even if “consistent and coordinated federal standards” that “apply nationally” render consideration of EPCA preemption unnecessary, as the 2010 and 2012 rules incorrectly contend, Democratic administrations scuttled the so-called national program not once but twice.

Trashing SAFE I

In the Trump administration’s September 2019 SAFE 1 Rule, NHTSA determined that EPCA 32919(a) preempts California’s tailpipe CO2 standards and ZEV mandates. The EPA, partly in affirmation of NHTSA’s preemption analysis, but also because vehicular CO2 emissions in California have no relevance to the state’s air quality challenges, withdrew the 2013 EPA waiver for California’s ACC program, including its ZEV mandates for model year 2017-2025 motor vehicles.

The Biden administration EPA could not reinstate the EPA waiver for the ACC program, much less grant a waiver for ACC II, without repealing SAFE 1. Accordingly, one might suppose the Biden administration would present a detailed rebuttal of SAFE 1’s preemption argument.

However, that is not what the Biden administration did. Rather, NHTSA’s December 2021 SAFE 1 Repeal Rule simply “withdraws” SAFE 1’s preemption analysis without rebutting or even summarizing it.

Yes, NHTSA acknowledged EPCA 32919(a) preempts state laws or regulations “related to” fuel economy standards but professed agnosticism about which types of state standards might be “related.” As if the agency had not been administering the EPCA program for the previous 46 years.

Indeed, NHTSA even acknowledged the agency had interpreted EPCA preemption along the lines of SAFE 1 in its 2006 (71 FR 17566, 17654-17670) and 2003 (68 FR 16868, 16896) CAFE standards rulemakings. But here too, NHTSA announced it was “withdrawing” those views without summarizing them or explaining why it no longer considered them valid.

This peculiar behavior is not hard to explain. The proposition that policies regulating or prohibiting tailpipe CO2 emissions are directly or substantially related to fuel economy standards is very close to being self-evident. The mind assents as soon as it understands the terms in which the proposition is framed.

The SAFE 1 Repeal Rule was a travesty of reasoned decision making. NHTSA was tied to a position it could not defend by an agenda (forced national vehicle electrification) it could not admit.

Unlawful ACC II waiver

In its December 2024 ACC II waiver decision, the EPA takes the position that the agency may not—or at least need not—consider EPCA preemption when reviewing California’s request for a waiver of Clean Air Act preemption (pp. 51, 179-180).

According to the EPA, its sole job under CAA 209(b) is to grant the waiver unless it makes one or more of three judgments: (A) California’s determination that its standards in the aggregate are at least as protective as federal standards is arbitrary and capricious, (B) the state does not need such standards to “meet compelling and extraordinary conditions,” or (C) such standards are inconsistent with CAA Section 202(a) requirements for adopting and enforcing federal vehicle emission standards. Thus, the EPA contends, it may not, or not need, consider any legal factors other than the three decision criteria specified in 209(b). That is incorrect.

Statutory construction is a holistic endeavor. As the Supreme Court stated in Food and Drug Administration v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp. (2000):

It is a “fundamental canon of statutory construction that the words of a statute must be read in their context and with a view to their place in the overall statutory scheme.” Davis v. Michigan Dept. of Treasury, 489 U. S. 803, 809 (1989). A court must therefore interpret the statute “as a symmetrical and coherent regulatory scheme,” Gustafson v. Alloyd Co., 513 U. S. 561, 569 (1995), and “fit, if possible, all parts into a harmonious whole,” FTC v. Mandel Brothers, Inc., 359 U. S. 385, 389 (1959).

A proper reading of CAA 209(b) must consider other parts of the CAA that provide context and shape its role in the overall statutory scheme. A relevant provision is CAA Section 110, which sets forth the requirements for State Implementation Plans (SIPs) under the national ambient air quality standards (NAAQS) program.

When repealing its portion of SAFE 1, NHTSA repeatedly invoked the “federalism interests” of California and other states seeking to incorporate ZEV mandates into their SIPs. The EPA’s ACC II waiver decision document makes the same argument (p. 181).

And there’s the rub. As Marc Marie points out, CAA Section 110(a)(2)(E) states that each SIP “shall … provide necessary assurances” the state is “not prohibited by any provision of Federal or State law from carrying out such implementation plan or portion thereof.” The EPA is responsible for reviewing SIPs and approving or rejecting SIP elements. Therefore, when the EPA reviews a waiver request under CAA 209(b), it may not turn a blind eye to potential conflicts between SIP elements contained in the waiver request and other federal statutes. It may not ignore EPCA 32919(a), which expressly and impliedly prohibits California’s ZEV mandates.

Conclusion

Multiple acts of regulatory evasion, prevarication, and usurpation propped up California’s automotive central planning ambitions for many years. The House and Senate’s CRA votes upend this unlawful power grab that threatens to price millions of Americans out of the market for new cars, undermine US automakers’ competitiveness by forcing them to discontinue many of their best-selling models, and rob Americans of their freedom to purchase the types of vehicles that best meet their needs.

It is now President Trump’s turn to deliver the coup de grace. Restoring the rule of law in the US automotive sector will foster a more competitive auto industry, happier consumers, and a freer society.