States can keep Medicaid whole if they want

Photo Credit: Getty

Congress is considering slowing Medicaid growth over the next 10 years enough to reduce federal spending by $625 billion. Many Republicans argue that the federal share of spending has increased substantially over the past 10 years and that the program’s growth needs to be constrained going forward. Further, if the federal government spends less, Republicans argue, the states can make up the difference themselves with state revenues.

Democrats say that that’s not possible, that state budgets are maxed out. Left-leaning health care analysts concur. However, recent history suggests that states have the capacity to make up for these changes with minimal impact.

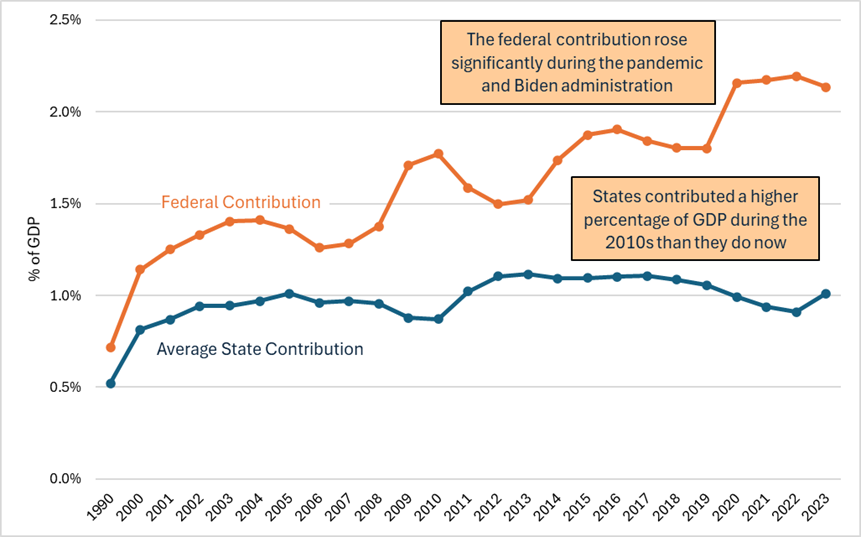

During the 2010s, states contributed a higher proportion of their economies to Medicaid than they do now. From 2012 to 2018, states contributed, on average 1.10 percent of GDP to Medicaid, peaking in 2013. During and after Covid, that contribution fell below 1 percent. In fact, these numbers potentially are misleading and states are contributing even less than they suggest because of increased use of the provider tax gimmick. With the increased use of provider taxes and state directed payments, the actual burden on state taxpayers is lower given the circular nature of using provider taxes to pay for health care.

State and federal Medicaid expenditures as a percentage of GDP

Those higher levels of contribution from the 2010s suggest that states have room to increase their own support of Medicaid beyond current levels.

Even as a percentage of state budgets, according to MACPAC, states have been contributing less to Medicaid.

In fact, by my calculations, if states were to match the peak contribution during the Obama administration, they would increase spending on Medicaid by almost $400 billion, nearly two-thirds of the reduction in expected federal payments.

To replace all $625 billion of the reduced spending, states would need to bump up their own contribution to Medicaid by an additional 0.06 percent of GDP. This would amount to raising their Medicaid expenditures by less than 6 percent from their 2013 peak. They could do this either by raising revenues or diverting funds from other programs.

Further, if the goal were to maintain Medicaid at current levels of GDP without any further expansion, states could accomplish that even more handily. Doing this would cost only $81 billion. If they wanted to allow for the higher levels of medical inflation, only $97 billion.

Whatever the goal, states have demonstrated they have the fiscal capacity to replace at least two-thirds of the proposed reductions in spending growth. Congress should not fret shifting some of that burden back to the states considering the responsibility those states have for the huge run-up in expenditures.