The Constitutional Cure for the Paris Agreement

Today marks the first anniversary of President Trump’s Rose Garden speech announcing his intention to withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement. That speech was a pivotal moment in the great unraveling of President Obama’s regulatory assault on fossil fuels. Mr. Trump’s steely resolve to protect America’s emerging “energy dominance” was now beyond dispute.

Today marks the first anniversary of President Trump’s Rose Garden speech announcing his intention to withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement. That speech was a pivotal moment in the great unraveling of President Obama’s regulatory assault on fossil fuels. Mr. Trump’s steely resolve to protect America’s emerging “energy dominance” was now beyond dispute.

Energy Dominance vs. Deep De-Carbonization

Where Obama disdained fossil fuels as “dirty” relics of a bygone era, Trump celebrates the nation’s “vast energy resources” and champions Americans’ freedom to produce coal, oil, and natural gas. Through market-driven energy development, Trump seeks to boost economic growth, create new jobs, lower energy prices, make U.S. manufacturers more competitive, and strengthen America’s geopolitical influence vis-à-vis Russia and OPEC.

Trump correctly understands that sticking with Obama’s Paris Agreement emission-reduction pledge, the so-called U.S. nationally determined contribution (NDC), is a death knell for most of the U.S. energy sector. To be sure, many fossil-fuel producers could survive the NDC’s plan to reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions 26-28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025. However, few investors want to park their capital in industries the U.S. government has targeted for punitive regulatory treatment.

Moreover, the 26-28 percent target is just the initial phase of a steadily tightening chokehold. By design, the Obama administration’s NDC is “consistent with a straight line emission reduction pathway from 2020 to deep, economy-wide emission reductions of 80 percent or more by 2050.” It is “part of a longer range, collective effort to transition to a low-carbon global economy as rapidly as possible.”

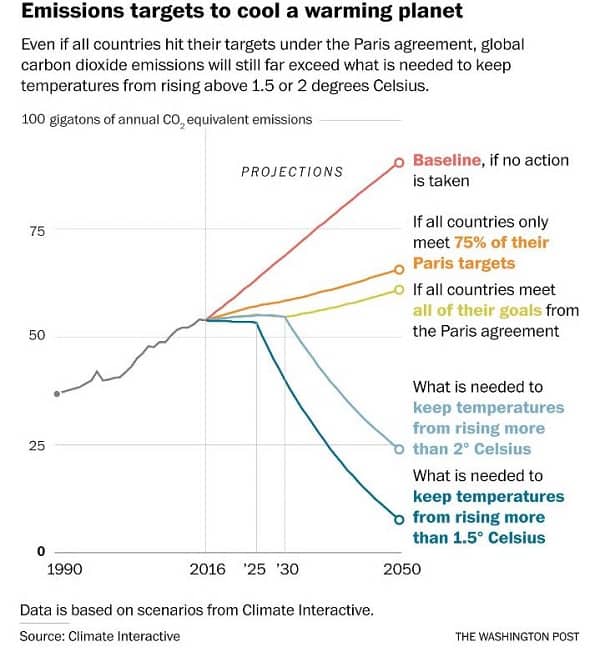

Had Hillary Clinton won the 2016 presidential election, the U.S. government would today be charging down the “path to deep de-carbonization.” The allegedly scientific basis of the Agreement is the collection of dubious, overheated models underpinning the UN’s climate assessment reports. Based on those models, global fossil fuel consumption must start declining by 2030 if the world is to avoid 2°C of warming by 2100—the treaty’s central goal.

In short, absent technological breakthroughs that make carbon capture technology cheap and scalable, American energy dominance and deep de-carbonization are conflicting agendas. Trump is to be congratulated for recognizing their incompatibility and choosing the right one.

Legal Chicanery

Unsurprisingly, all manner of special pleaders—former Obama officials anxious to preserve their handiwork, State Department officials keen to grow the climate diplomatic corps, carbon tax advocates licking their chops at the prospect of a global vehicle for their agenda, and even fossil-fuel companies seeking new rationales to subsidize carbon capture and enhanced oil recovery projects—have tried to persuade President Trump that he does not have to exit the Paris Agreement to reject Obama’s NDC. According to them, Trump may discard Obama’s emission-reduction pledge without breaking any official U.S. commitment.

That is flimflam—a ploy to keep America in the fossil-fuel haters club until the next establishment Republican or progressive Democrat becomes president and picks up where Obama left off. The pertinent provision of the Agreement, Article 4.11, states: “A Party may at any time adjust its existing nationally determined contribution with a view to enhancing its level of ambition.” The Paris pleaders claim the provision alternatively means that a party may at any time decrease its level of ambition.

No such thing is either stated or implied in the text. Indeed, if Article 4.11 authorized parties to weaken their commitments at any time, it would make hash of the Agreement’s core architecture. Article 4.3 requires each party every five years to submit a new NDC that “will represent a progression beyond the Party’s then current nationally determined contribution and reflect its highest possible ambition.” That ratchet mechanism is what most distinguishes the Agreement from previous climate pacts. Such quinquennial exercises have little point if, “at any time” in between, a party may replace its existing NDC with a “commitment” reflecting its lowest possible ambition.

Besides, the notion that an NDC, once submitted, may be rescinded “at any time” turns words like promise, pledge, and commitment into gibberish. “I didn’t break my promise to pick up the kids after school,” the climate activist told his wife, “I adjusted it with a view to decreasing the level of ambition so I could have drinks with the guys instead.”

Granted, NDCs are “non-binding” (unenforceable) under international law. However, that merely means promise breakers incur no legal penalties such as trade sanctions. It does not mean each party may retract its promise to avoid being “named and shamed” for breaking it.

Misdirection

The artificial controversy over the meaning of “may . . . adjust” in Article 4.11 is a classic case of misdirection. Clever lawyers naturally want us to believe that textual minutia, not the massive political and economic interests that affect us as citizens, consumers, and bread winners, should determine public policy. The big picture obscured by such pedantry is this. Even if the Agreement did authorize Trump to tear up Obama’s NDC, remaining in the pact would still endanger America’s economic future and political independence.

Through an endless procedural churn of committee meetings, annual climate summits, and five-year mega summits, where the main business is monitoring, reporting on, and verifying each party’s climate policies, the Paris Agreement is designed to mobilize a global, multi-decade, political pressure campaign. A key objective of such pressure is to keep U.S. leaders committed to deep de-carbonization via strategies such as cap-and-trade, Clean Power Plan-style regulation, “keep it in the ground” restrictions on energy development, and billions in “climate aid” for developing countries—the very policies Mr. Trump campaigned against and is rescinding.

Whether America should stay in or pull out of the Paris Agreement comes down to a very simple question. Should we remain in a club organized to pressure us into acting against our best interests and better judgement? If, as Mr. Trump believes, a thriving domestic energy sector is in the national interest, prudence dictates that we exit the Paris Agreement as quickly and irreversibly as possible.

The Constitution Solution

Article 28 of the Paris Agreement provides two withdrawal options. A nation may withdraw from the parent treaty, the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), in which case withdrawal takes effect in one year. Or, a nation may withdraw from the Paris Agreement itself. In that case, a nation must wait until three years after November 4, 2016, the date on which the Agreement entered into force, to submit a notification of withdrawal. Then it must wait an additional year for withdrawal to take effect. If President Trump uses that method, America is not out of the Paris Agreement until the day after Election Day 2020.

Consequently, using the slow option would allow the next president to put us right back in 2021. The U.S. energy sector would face the same sort of political risks it did under the Obama administration. The Trump presidency could end up being a mere bump on the road to deep de-carbonization.

Fortunately, the quickest and most durable way to safeguard U.S. energy producers from the Paris pressure regime is to revive the constitutional treaty process.

President Obama rightly called the Paris Agreement the “most ambitious climate change agreement in history.” Because of the automatic quinquennial ratchet mechanism, the Paris Agreement is more ambitious than either the UNFCCC or the Kyoto Protocol, both which are indisputably treaties subject to the Constitution’s advice and consent process. Nor is that all. When we consider that the climate system embraces the Earth’s oceans and atmosphere, and that the Paris Agreement calls for the transformation of energy policies, markets, and infrastructure on a global scale, the Agreement is easily the most ambitious environmental agreement in history.

Yet President Obama claimed he could adopt the Agreement on his sole authority as chief executive—as if it were on a par with the bilateral executive agreements the Bush administration negotiated with Congo, Niger, and Ethiopia to promote environmental education in primary and secondary schools.

Under Article II, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution, “The President . . . shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur.” The Paris Agreement is a treaty by virtue of its costs and risks to the nation as a whole, dependence on subsequent legislation by Congress, and other traditional criteria. President Obama claimed the Paris Agreement was not a treaty because he knew that even when Democrats were in the majority, “two-thirds of the Senators present” would not approve new international climate commitments.

The constitutional way to safeguard America’s emerging energy dominance is to submit the Paris Agreement to the Senate with the recommendation that it be voted down. There is even less chance today than there was during the Obama administration that the Senate would give its consent to ratify the treaty.

This approach has two great advantages over Article 28’s slow withdrawal procedure. First, America would effectively be out of the Paris Agreement as soon as the Senate votes. Second, once the Agreement is rejected and exposed as lacking broad public support, few if any future presidents would attempt to rejoin it on their sole authority. Or, if a future executive did so, the people and their representatives would be more likely to recognize and oppose such overreach.

My colleague Christopher Horner puts the matter well in a recent press release:

We hope President Trump will consummate the announced withdrawal, preferably more durably than the continued pen-and-phone tit for tat—each such unilateral act being subject to a unilateral reversal. He should resolve this attempted end-run around our Constitution by doing what the French, Germans, Italians, and others did: send it to the elected body that has the express, constitutional role for approving these types of commitments.