The Endangerment Finding’s disqualifying systemic biases, part 2

Photo Credit: Getty

The previous post in this series documented the 2009 Greenhouse Gas Endangerment Finding’s reliance on overheated models and inflated emission scenarios to estimate climate change risks. Today’s post spotlights a third systemic bias — ignoring the power of adaptation to promote climate safety and human flourishing.

The Obama-era EPA determined that potential adaptive responses to climate change are “outside the scope” of an endangerment analysis. That decision exacerbated the alarmism already baked into the assessment by running warm-biased models with warm-biased emission scenarios.

The EPA argued it would be as inappropriate to consider potential adaptation to a changing climate as it would be to “consider the availability of asthma medication in determining whether criteria pollutants endanger public health.”

But excluding adaptation was neither scientific nor even reasonable. One might as well speculate about the health risks of winter weather without considering the availability of warm clothes, heated buildings, health clinics, or chicken soup. Or assess the food security risks of drought without considering the availability of irrigation or trade with food surplus regions.

Moreover, the EPA’s analogy between carbon dioxide (CO2), the main anthropogenic GHG, and criteria pollutants, is strained at best. Criteria, toxic, and radiological pollutants endanger health or welfare via direct routes of exposure such as inhalation, dermal contact, or ingestion. In contrast, CO2 is non-toxic to humans and animals at any concentration projected to result from fossil fuel combustion, and the ongoing rise in atmospheric CO2 concentration has substantial agricultural and ecological benefits.

For criteria pollutants, toxic pollutants, and radiological pollutants, public policy aims to reduce or eliminate dangerous exposures. In other words, for such pollutants, “adaptation” is primarily mitigation, whether in the form of pollution control and prevention, remediation, or measures to isolate toxins from people or other living things.

Carbon dioxide-related risks arise not from exposure but from potential changes in weather and sea levels on multi-decadal scales. Accordingly, adapting to a changing climate chiefly requires the sorts of economic, engineering, and behavioral decisions people have made to better their lives since time immemorial. That process indisputably improves health, safety, and comfort in diverse (often harsh) climatic conditions.

The EPA did not explain why it should disregard the availability of asthma medications — or hazmat suits, for that matter — when determining whether air pollution endangers public health. Two reasons leap to mind. First, the types of protective gear worn by firefighters and other first responders are not a practical solution for daily use by the public. Second, no one would suggest that someone receiving medical treatment for a toxic exposure is better off than someone who was never contaminated in the first place.

Adaptation is part of the virtuous cycle of progress that, in the modern warming period, has increased global average life expectancy by 58 percent since 1950, global per capita income by 292 percent since 1960, and global per capita food supply by 35 percent since 1961.

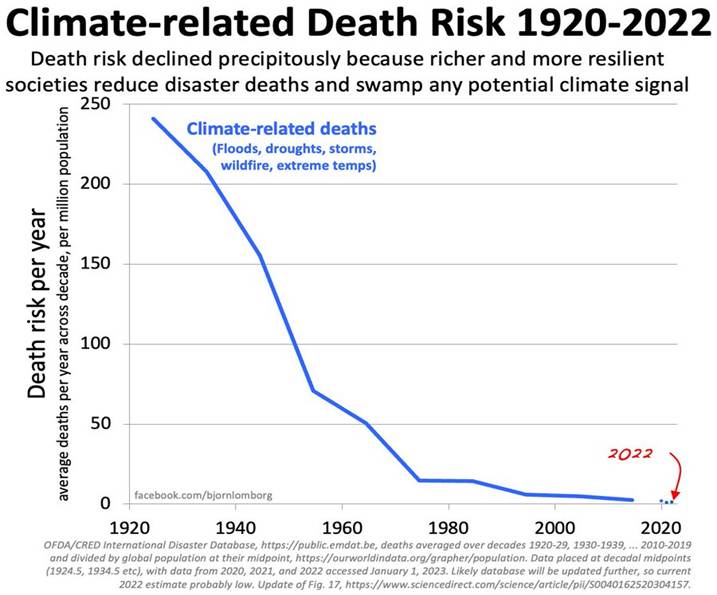

More critically, adaptations driven by the pursuit of happiness, market dynamics, and prudent policies increasingly protect humanity from extreme weather. Globally, the decadal annual average number of deaths due to droughts, floods, wildfires, storms, and extreme temperatures declined from about 485,000 per year in the 1920s to about 14,000 per year in the past decade — a 96 percent reduction in annual climate-related mortality.

Factoring in the fourfold increase in global population since the 1920s, the average person’s risk of dying from extreme weather today is more than 99 percent lower than it was a century ago.

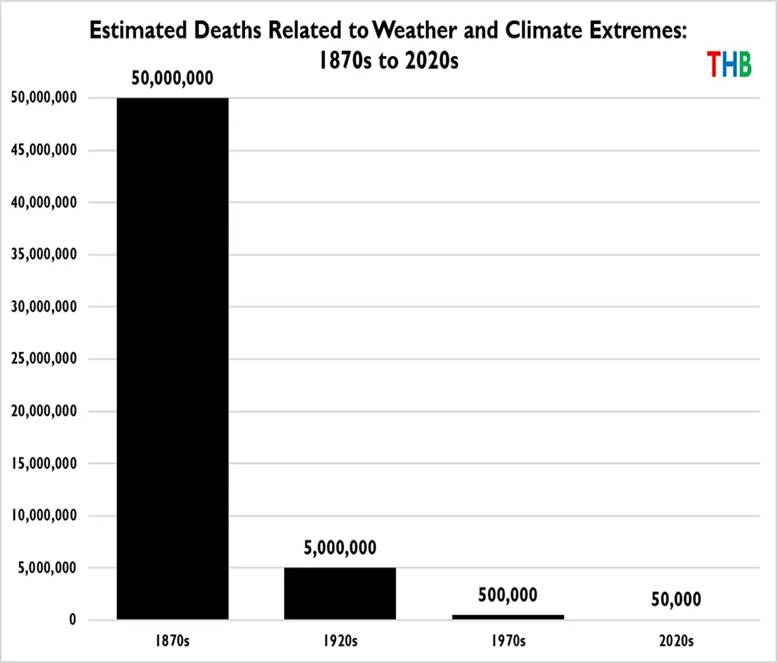

Equally impressive, over the past century and a half, global decadal weather-related deaths have decreased by an order of magnitude every 50 years, as natural disaster expert Roger Pielke, Jr. shows in the next chart.

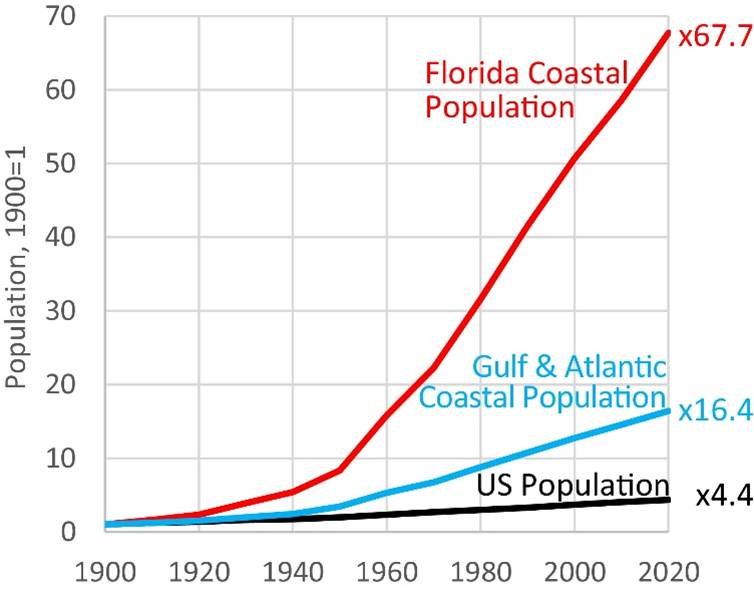

Granted, total climate-related economic damages are increasing, but that is chiefly due to increases in population and exposed wealth — what Danish economist Bjorn Lomborg calls the “expanding bull’s eye effect.” For example, since 1940, “Florida’s 35 coastal counties have increased a phenomenal 67.7 times, from less than a quarter-million to over 16 million in 2020.” Economic development continually puts more property and infrastructure in harm’s way.

From a sustainability perspective, what matters is not absolute damages but relative economic impact — losses as a share of GDP. Climate researchers Giuseppe Formetta and Luc Feyen estimate that, as a percentage of exposed wealth, global extreme weather damage declined almost five-fold from 1980-1989 to 2007-2016.

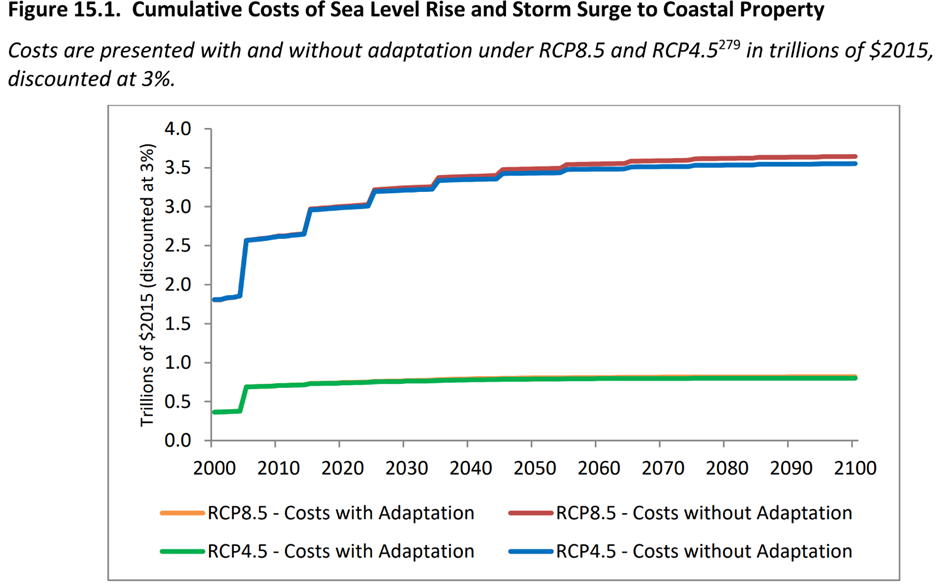

Although the EPA excluded adaptation from its 2009 Endangerment Finding, its 2017 Sectoral Impacts Analysis, a technical report for the Fourth National Climate Assessment (NCA4), estimates that “proactive adaptation” could decrease 21st century climate change damages to US roads by 98 percent under the RCP8.5 (the “severe” emissions scenario) and 83 percent under RCP4.5 (the “moderate” scenario).

Strikingly, according to the sectoral analysis, reducing RCP8.5 emissions to RCP4.5 levels would reduce 21st century US coastal property damages by only 2.6 percent — from $3.6 trillion to $3.508 trillion. In contrast, proactive adaptation could decrease US coastal property damages by 77 percent, from $3.6 trillion to $880 billion. Combining mitigation with adaptation would barely enhance the latter, reducing coastal property damage by a further $20 billion or 0.5 percent. Indeed, the additional coastal protection benefit from reducing RCP8.5 emissions to RCP4.5 levels is almost invisible in the chart below.

Adaptation’s full potential may be greater still. In his book False Alarm, Bjorn Lomborg reviews Hinkel et al. (2014), a sea-level rise study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The study includes a scenario in which RCP8.5 warming and sea level rise flood up to 4.6 percent of global population in 2100, with annual losses up to 9.3 percent of global GDP.

However, those extraordinary damages occur only if people do nothing more than maintain current sea defenses. If “enhanced” (anticipatory) adaptive measures are taken, flood damages in 2100 are “2-3 orders of magnitude lower.” Yes, annual flood damages and dike costs would increase by tens of billions of dollars. But Lomborg calculates the relative economic impact of coastal flooding would decline sixfold from 0.05 percent of global GDP in 2000 to 0.008 percent in 2100. Moreover, the annual average number of flood victims would decline by more than 99 percent — from 3.4 million in 2000 to 15,000 in 2100.

In short, even in a high-end warming scenario, forward-looking adaptation could make coastal flooding less disruptive and damaging than it is today. To exclude that type of analysis from an endangerment determination is unreasonable.

Overheated models, inflated emission scenarios, and lame adaptation assumptions drove the Endangerment Finding’s conclusion that rising GHG concentration “may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare.” Today’s EPA should consider a different conclusion: Societies that protect economic liberty and welcome abundant energy may reasonably anticipate a future of increasing climate safety and economic stability.

Note: This post was expanded on November 25, 2025.