The executive order explosion: When counting counts

Photo Credit: Getty

What stands out in the Trump administration is the unnerving tension between executive orders (EOs) that shrink government and those that expand it.

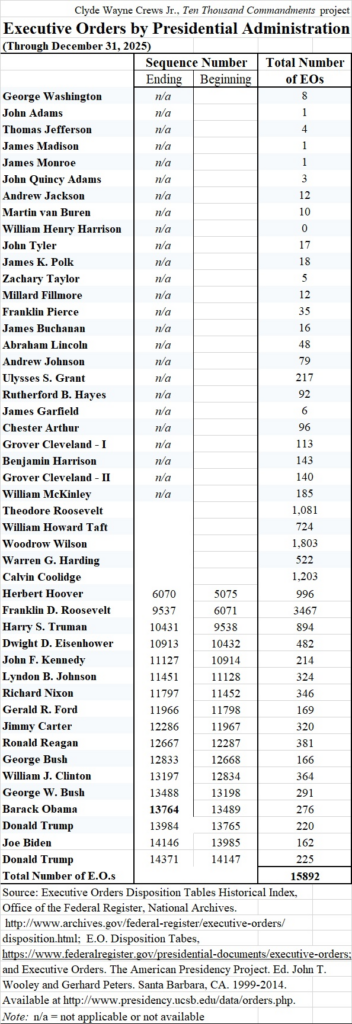

EOs date back to George Washington, but their systematic cataloging and archiving is a relatively modern phenomenon. Since the nation’s founding, presidents have issued at least 15,892 executive orders. The United States was several decades old before a president issued more than two dozen EOs during a single term, as Franklin Pierce did between 1853 and 1857. Totals remained in the single digits or teens until Abraham Lincoln’s wartime consolidation of federal authority and the subsequent Reconstruction period. Ulysses S. Grant’s 217 executive orders set a 19th-century high mark.

The modern era is different. Since the 20th century, every presidency has produced well over 100 executive orders with some administrations issuing them by the thousands. Franklin D. Roosevelt issued 3,467 executive orders over an interval spanning the Great Depression and World War II. His record looms large because of its scale and because it normalized the idea that executive directives are an acceptable substitute for legislation during emergency or crisis.

To be sure, we should welcome and applaud executive controls internal government spending, contracts, and regulatory processes when they expand individual liberties and reduce coercive federal interventions.

But the normalization of interventionist EOs has never been reversed, such that even emergency rationales are no longer required.

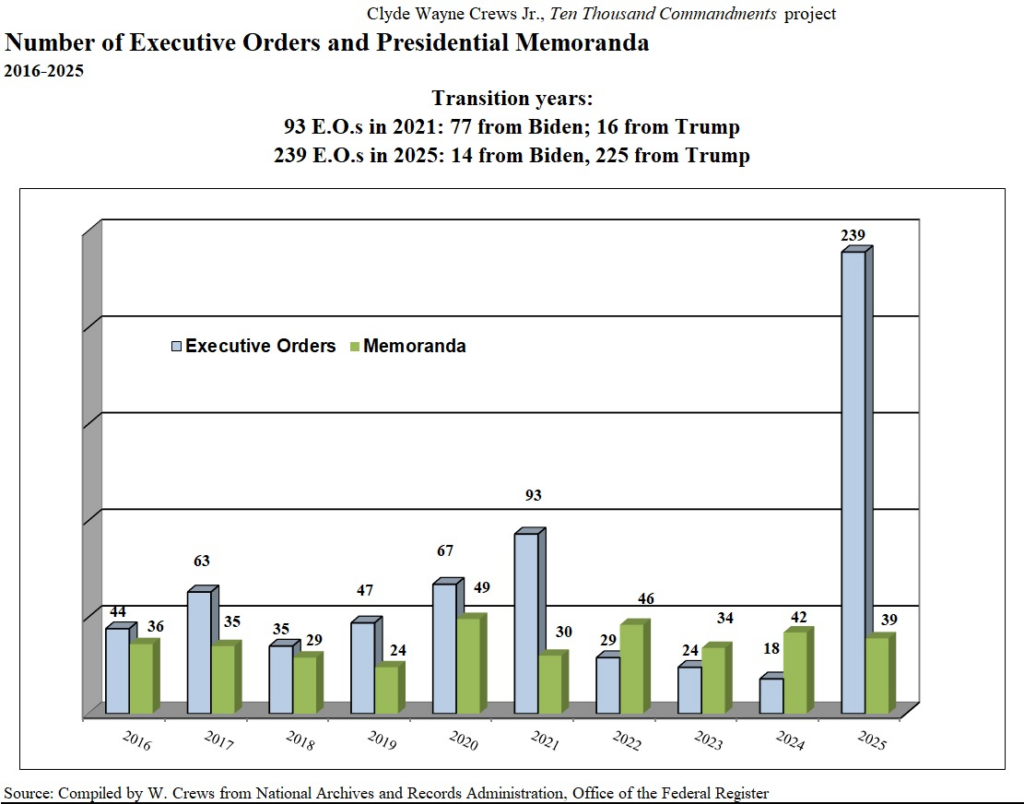

Let’s look at where we stand after one year of the second Trump administration. The 239 executive orders published in calendar year 2025 stand out sharply in the modern era, representing a 1,228 percent increase over 2024 levels. Of those, Joe Biden issued 14, while Donald Trump issued 225.

Accounting for overlap in transition years, recent administrations break down as follows:

- Bill Clinton (1993–2000): 364 executive orders, 46 per year

- George W. Bush (2001–2008): 302 executive orders, 38 per year

- Barack Obama (2009–2016): 291 executive orders, 36 per year

- Trump first term (2017–2020): 212 executive orders, 53 per year

- Biden (2021–2024): 164 executive orders, 41 per year

But counting executive orders misses the more important question: what kinds of executive orders are being issued, and what institutional repair — or damage — might they cause?

Admirably, executive orders sometimes aim at regulatory review and streamlining as distinct from their popularity for implementing policy. In that respect EOs are often not just benign but vital tools for internal management or administrative housekeeping. This subset includes Ronald Reagan’s EO 12291 that centralized regulatory oversight at the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Bill Clinton’s EO 12866 retained that framework, but reaffirmed agency primacy. Biden’s EO 14094, “Modernizing Regulatory Review,” went in the opposite direction — softening cost-benefit discipline, raising the threshold for what counts as a “significant” regulation and biasing OMB methodology toward finding regulations as uniformly net-beneficial.

Trump in 2025 revoked Biden’s framework and replaced it with an aggressive streamlining regime, prominently featuring regulatory budgeting and a one-in, ten-out model. Several of these orders explicitly invoked the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) in an overarching regime encompassing directives on workforce optimization, cost efficiency, reducing anti-competitive barriers, and enshrining zero-based regulatory budgeting in energy rulemaking. EO 14215 is particularly notable for extending OMB review to independent agencies such as the Federal Communications Commission for the first time.

These are deregulatory executive orders — procedural and aimed at restraining administrative sprawl. They are not the problem.

The problem is a parallel class of executive orders that operate as stand-alone regulatory regimes — what I have often referred to as Trump’s discordant “swamp things.” These directives do not streamline anything; they substitute executive command for legislation and embed new federal control and bloat that will be difficult to unwind.

Tariff executive orders are a prime example, of course, altering prices economy-wide and entrenching permanent administrative shenanigans. The same interventionist impulse shows up in Trump’s price-control forays such as those involving drug pricing and concert ticket and venue pricing (the latter memorably during Trump’s Oval Office appearance alongside Kid Rock).

A new executive order just announced on January 21 is “Stopping Wall Street from Competing with Main Street Homebuyers,” a move my colleague John Berlau warns can backfire as it can hurt housing availability and undermine the genuinely deregulatory housing reforms Trump pursues elsewhere, such as ending counterproductive energy mandates and opening access to federally-owned property for construction.

Other prominent interventions include platform-specific forced divestiture directives, such as the TikTok ban, that benefit specific firms, partial nationalizations of firms like Intel, and federal steering of emergent artificial intelligence through the likes of conditional subsidies for favored firms or ventures. These and other industrial policy forays preload regulation, which shifts default authority to the administrative state and crowds out competitive market disciplines, blurring distinctions between regulation, spending, and ownership itself.

Bottom line: some executive orders deregulate, but others regulate — badly and illegitimately.

Deregulatory orders are fragile and easily reversed unless Congress backs them up.

Regulatory executive orders, however, accumulate, metastasize, and entrench. They outlive administrations like Trump’s because they affirm the premises of progressives who have sought governmental control over the economy for more than a century. Along with over-regulation of the conventional kind, they displace Congress as the primary lawmaking institution.

The real executive order crisis is not their number, despite Trump’s Roosevelt-like record setting new tally. It will take boatloads of executive orders to dismantle parts of a $7 trillion government, where they can legitimately be used to do so.

While they can do some good when they constrain government, executive branch decrees too often fail to perform that function. Today, executive orders — alongside other forms of presidential and executive branch regulatory dark matter that we often detail — too often embody rule of flaw rather than rule of law. They too often set precedents that any future power-mad president — of any party — can and will inevitably exploit.

“Presidential documents: A baseline to curb the pen and phone,” Forbes

“Framing an ‘Abuse-of-Crisis Prevention Act’ to Confine the Federal Government,” Social Science Research Network