The FTC Targets Apple Music: Part II

This is the second in a series of essays on the FTC’s investigation of Apple Music. Part I discussed the reason for the FTC’s investigation as well as the facts behind the allegations levied at Apple. This part will look at the situation from an economic perspective and examine the extent to which competition in the market for smartphones would mitigate any threat to competition in the music streaming market arising due to Apple’s supposedly anti-competitive actions.

Before we consider the competitive effects of Apple’s actions, it’s important that we investigate the extent to which the severity of Apple’s actions is even relevant. Consider the following thought experiment:

Assume that Apple were to unilaterally ban all music streaming companies from offering iOS apps, thereby granting itself a monopoly in the market for iOS music streaming. Would this pose a significant threat to competition?

The instinctual answer is, ”Yes! Obviously the act of outlawing competition is a significant threat to competition.” In reality, however, the question is more complicated. Although Apple has monopoly power in its iOS ecosystem, its need to compete with Android devices in the overall smartphone market limits the extent to which it can exploit this power.

Consider the “Apple Tax,” which, as mentioned in part I, is the 30 percent “tax” Apple imposes on all purchases made through its App Store or through any iOS apps. At the moment, this tax is significant but not unreasonable. But imagine what would happen if Apple were to begin raising it, to 50 percent, 70 percent, 90 percent. As it grew higher and higher, app creators would spend less and less time making apps for iOS, and any paid apps made would become progressively more expensive. Consequently, consumers would increasingly switch to competing smartphone brands (presumably those running Google’s Android operating system).

The extent to which a change in the price of one good can lead to a change in the demand for another is referred to as the cross elasticity of demand and is critical to understanding our earlier hypothetical. Here, we are interested in the extent to which an increase in the total cost of ownership of an iPhone—realized as an increase in the price of music streaming apps on iOS—would drive consumers to switch to competing smartphone brands. A greater cross elasticity of demand would indicate higher consumer willingness to switch and, thus, would suggest that Apple’s actions in our hypothetical are less likely to pose a significant threat to competition.

Interchangeability

Of the many factors which contribute to a set of products’ cross elasticity of demand, the most straightforward is those products’ interchangeability—their ability to serve as substitutes for each other. Imagine two products that are functionally identical but different colors. Each of these products would serve as an effective substitute for the other and, consequently, these products would likely possess a high cross elasticity of demand. On the other hand, consider a treadmill and an elliptical. Although these products serve similar purposes, and each could serve as a replacement for the other, they are far from perfect substitutes. As a result, they would likely possess a much lower cross elasticity of demand.

In looking at smartphones, there are four primary channels through which differentiation can arise: hardware, operating systems, apps, and branding.

1. Hardware. For the sake of simplification, let's compare the iPhone 6 to the Galaxy S6, its most popular competitor. As is evident from this comparison chart, the hardware used in the Galaxy and the iPhone is remarkably similar. The Galaxy actually has the advantage in a few key areas, namely its RAM (3 GB vs 1 GB), its front camera resolution (5 MP vs 1.2 MP), its rear camera resolution (16 MP vs 8 MP), and its display resolution (1440p vs 1080p or 750p). Consider that the Galaxy S6 was released half a year after the iPhone 6, and it’s reasonable to conclude that they’re roughly equivalent from a hardware perspective. The sheer number of Android phones available, all with slightly different hardware configurations, further suggests that hardware concerns would be unlikely to ever act as a barrier to switching from an iPhone to an Android phone.

2. Operating Systems. iOS, the operating system installed on Apple’s iPhones, and Android, the operating system installed on most of its competitors’ phones, are also reasonably similar. Both incorporate the same set of core features, and, for the most part, have implemented these features in the same way. The primary difference between the two operating systems lies in their attitudes towards customization. Android is significantly more customizable than iOS, allowing users to change the default apps used to perform actions or open links, add widgets to their home screens, and even install custom launchers. Apple’s iOS allows none of this, opting instead for a set of “smart defaults.” Although users can certainly become attached to a given setup, it is unlikely that the differences between iOS and Android would act as a significant barrier to switching from an iPhone to an Android phone.

2. Operating Systems. iOS, the operating system installed on Apple’s iPhones, and Android, the operating system installed on most of its competitors’ phones, are also reasonably similar. Both incorporate the same set of core features, and, for the most part, have implemented these features in the same way. The primary difference between the two operating systems lies in their attitudes towards customization. Android is significantly more customizable than iOS, allowing users to change the default apps used to perform actions or open links, add widgets to their home screens, and even install custom launchers. Apple’s iOS allows none of this, opting instead for a set of “smart defaults.” Although users can certainly become attached to a given setup, it is unlikely that the differences between iOS and Android would act as a significant barrier to switching from an iPhone to an Android phone.

3. Apps. Both Apple’s iTunes App Store and Google’s Google Play Store offer their users vast catalogues of apps to choose from. As of January 2015, there were approximately 1.2 million iPhone apps available in the iTunes store, compared to approximately 1.4 million Android apps in the Google Play store.* But if anyone has an advantage when it comes to apps, it is Apple. First, it is common for new releases to come to iOS before Android, a consequence of the difficulties associated with coding for the myriad Android devices available. Although any successful app—and many unsuccessful ones—will almost inevitably come to Android, there is sometimes a delay. This delay may serve as a small disincentive for users considering switching to Android. A second disincentive is Apple’s refusal to release Android versions of many of its proprietary apps. As a result, many of the default iPhone apps—Maps, Safari, Mail, for example—aren’t available on Android. Although there is no shortage of competent—even superior—replacements on Android, the need to abandon the comforting familiarity of one of Apple’s apps and learn to use a new one in its place may discourage users considering switching. On the whole, however, these disincentives are closer to minor inconveniences than to major barriers. Both iOS and Android offer rich ecosystems of apps, and although differences exist, they are relatively minor.

4. Branding. Branding is the one area in which there is a significant difference between the iPhone and its competitors. Although many Android devices rival the iPhone’s stylish design, they will always lack the Apple brand—a brand which a number of different publications all ranked as the most valuable in the world. Regardless, it would be absurd to conclude that Apple’s brand value in and of itself serves as a serious barrier to the interchangeability of the iPhone and its Android competitors. The extent to which a company “abuses” the value of its brand should be of no concern to antitrust regulators. Were it considered a concern, the ramifications would be severe—and absurd. Rolex, Louis Vuitton, Mercedes Benz, and a whole host of other luxury brands would all become targets; in fact, it would constitute an attack on the very concept of a luxury brand. Yet trademark law not only permits companies to extract value from their brand, it encourages them to do so by forbidding counterfeiting and other forms of brand dilution. Moreover, any reliance on branding as a means of preventing users from switching would be checked by the fact that Apple’s brand is reliant on the company’s reputation, which would be damaged by any decision to engage in anti-competitive actions. Consequently, we can conclude that although there is a significant difference in branding between the iPhone and its Android competitors, this difference shouldn’t be considered a legitimate barrier to interchangeability and, as such, shouldn’t be a cause for concern.

In conclusion, there are Android phones which, despite a number of minor differences, would serve as effective substitutes for the iPhone. This is good for competition; it indicates that we can expect a higher cross elasticity of demand, which in turn suggests that Apple’s ability to exercise excessive market power in its iOS ecosystem will be limited.

Availability and Cost of Information

Another factor which contributes to the cross elasticity of demand of a set of products is the extent to which information on those products is cheaply and readily available. The greater the availability of product information, the more capable consumers are of reacting to any anti-competitive actions and the higher the cross elasticity of demand. This effect becomes stronger when the product is expensive or the consumer is a repeat or experienced purchaser, as both of these traits make it more likely that consumers will actively seek out information on a product.

In the case of the smartphone market, the widespread availability of information, disseminated through a variety of traditional and alternative channels such as news sites, blogs, forums, and social media, has made becoming an informed consumer incredibly easy. Moreover, smartphones are expensive products and smartphone consumers—especially those on postpaid mobile contracts—are generally repeat buyers. These features of the smartphone market are yet another indicator that the cross elasticity of demand is likely to be high.

Sunk Costs

One additional factor which influences the cross elasticity of demand is the sunk costs associated with switching. Although sunk costs are a fallacy, they are one which, nevertheless, influences consumers’ decision making. Consumers’ bias towards loss aversion will drive some to avoid switching phones when it would be objectively advantageous to do so.

In the context of the smartphone market, the effect of sunk costs is exacerbated by the fact that any smartphone user wishing to abandon his current smartphone will need to not only get over the fact that he is “wasting” the money spent on his current phone but also commit himself to buying a new smartphone. Unlike the sunk cost associated with discarding a previously purchased smartphone, this additional cost is a rational disincentive for users wishing to switch.

Sunk costs in the smartphone market come in more than just one form; costs associated with replacing any accessories—such as cases, adapters, or docks—will further deter switching. Although a new smartphone will almost certainly come with essential accessories included, the difference in body shape and in connector type between the iPhone and its Android competitors would render any supplementary iPhone accessories useless to anyone switching to Android.**

Finally, users who rely on Apple’s iTunes or iBooks stores to purchase content other than music—such as television shows, movies, and books—would be unable to take that content with them to an Android device if they were to make the switch. Non-music content sold in these stores is limited by Apple’s FairPlay Digital Rights Management (DRM), which prevents users from consuming the content outside of Apple’s proprietary apps. As Apple hasn’t made any of these apps available on Android, customers of Apple’s iTunes and iBooks stores cannot legally consume their purchased content on an Android device. Anyone wishing to do so would have to remove the DRM from their content, an act which, although definitely possible, is illegal under 17 U.S.C. § 1201, not to mention inconvenient, and predicated on a certain, albeit relatively low, level of technical proficiency.

Although sunk costs have a tendency to drive down the cross elasticity of demand in the smartphone market, the prevalence of postpaid mobile contracts among smartphone users limits their power to inhibit consumer movement between different smartphone brands. These contracts, which typically last anywhere from one to three years, almost universally guarantee the customer a significant discount on a new phone upon entering into a new contractual period; thus, there are already significant incentives for many U.S. consumers to purchase a new smartphone—and in doing so, re-evaluate whether they want to buy an iPhone or an Android device—on a regular basis. As approximately 70 percent of U.S. mobile phone users are on postpaid mobile contracts, the effectiveness of these plans in limiting inelasticity due to sunk costs in the smartphone market is likely to be reasonably high.

Reputation

Up to this point, we have been discussing the cross price elasticity of demand—the extent to which a change in the price of one good will result in a change in the demand for another. In this section, we will examine the relationship between a company’s reputation and the demand for its products, a concept which l will refer to as the reputation elasticity of demand.

In our hypothetical, Apple’s decision to prohibit competing streaming services from offering iOS apps would not only increase the total cost of ownership of an iPhone; it would also damage Apple’s reputation. The question, then, is, “To what extent would a decline in Apple’s reputation lead to a decline in demand for the iPhone?” or equivalently, “How high is the reputation elasticity of demand of the iPhone?” A higher reputation elasticity of demand is good for competition because it indicates that the potential damage to a company’s reputation as a result of engaging in anti-competitive actions will serve as a stronger limit on the company’s willingness to engage in those actions.

In the case of the iPhone, it is reasonable to assume from Apple’s reliance on its brand—which, as mentioned earlier, is the most valuable in the world—to market and sell the iPhone that reputation is important to the company and, consequently, that the reputation elasticity of demand of the iPhone is relatively high. This reliance on branding is evident in Apple’s recent iPhone ads, all of which end with the slogan, “If it’s not an iPhone, it’s not an iPhone.” Apple has successfully created a unique identity for the iPhone. If this identity were to lose its positive connotation and instead take on a negative one, it would represent a devastating blow to both Apple and the iPhone.

The effectiveness of a high reputation elasticity of demand at mitigating any anti-competitive actions is not a constant, however. It depends heavily on the importance of future demand for the product, which, in turn, is primarily dependent on the growth rate of the product market. The faster a market is growing, the more revenue there is to be gained from future sales, and the more important future demand—and consequently, reputation—is likely to be. In the case of the global smartphone market, growth, although slowing, remains high. According to research firm Gartner, worldwide smartphone sales grew by 28.4 percent in 2014. Meanwhile, IDC is projecting year-over-year growth of 11.3 percent in 2015 and a compound annual growth rate of 8.2 percent over the five year period from 2015 to 2019.

These two factors—the iPhone’s high reputation elasticity of demand and the global smartphone market’s relatively high growth rate—should act as a powerful check on Apple’s ability to engage in anti-competitive behavior inside its iOS ecosystem.

Market Share

Before returning to our hypothetical, it is worth mentioning the attribute of a product most commonly associated with antitrust law: market share. In general, market share has less of an effect on the competitive effects of a corporation’s actions than the factors mentioned previously, for the simple reason that the possession of significant market share does not necessarily imply the possession of significant market power. For example, a company can have 90 percent market share, but if a perfect substitute for its product exists, it will barely be able to increase prices, if at all.

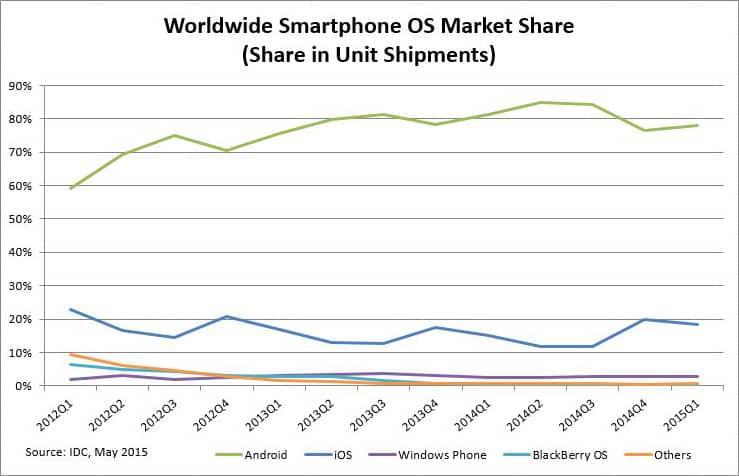

That said, there is some value to using market share as an indicator of market power. Consequently, it is worth noting that Apple possesses only 18.3 percent of the global smartphone market and only 43.1 percent of the U.S. smartphone market. IPhones may seem ubiquitous, but in reality they don’t even constitute a majority of the market.

That said, there is some value to using market share as an indicator of market power. Consequently, it is worth noting that Apple possesses only 18.3 percent of the global smartphone market and only 43.1 percent of the U.S. smartphone market. IPhones may seem ubiquitous, but in reality they don’t even constitute a majority of the market.

Back to Hypotheticals

Now, let’s return to our hypothetical, in which Apple prohibited all rival music streaming companies from offering iOS apps. Such a decision would create a significant incentive for iPhone users interested in using non-Apple music streaming services—or simply worried about a potential future rule banning rival e-readers, navigation apps, video services, or any number of other services—to replace their iPhone with an Android phone. The number of users that would actually switch depends on the cross elasticity of demand, which is likely to be relatively high—as we have shown by examining the interchangeability of the iPhone and competing Android phones, the availability of information about the market, and the sunk costs associated with switching phones. This finding echoes that of a 2010 study by Scott Cromar, which concluded, “Self-elasticity and cross-elasticity [in the smartphone market] are high. No one firm in the market has sufficient market share to control prices, resulting [in] strong rivalry and competitive pricing.” Moreover, as shown earlier, the combination of the iPhone’s high reputation elasticity of demand and the smartphone market’s relatively fast growth rate should severely constrain Apple’s ability to take any action which non-trivially damages its reputation in the eyes of consumers.

Granted, this isn’t a quantitative analysis, and it’s possible that even in spite of these mitigating factors, Apple’s hypothesized actions would have a net negative effect on competition. But the purpose of this thought experiment is to demonstrate that even if we take Apple’s “anti-competitive” actions to the extreme, the high price and reputation elasticities of demand associated with competition in the smartphone market would significantly limit any threat to competition.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll make the assumption that, contrary to the conclusions of this section, competition in the smartphone market has no mitigating effect on any anti-competitive actions engaged in by Apple and look instead at the extent to which Apple’s real-world actions are, in and of themselves, both pro- and anti-competitive.

*At Apple’s June Worldwide Developer Conference, CEO Tim Cook announced that the App Store had passed 1.5 million apps. I chose to use the slightly outdated January statistic in order to ensure that the numbers being compared were from the same point in time.

** Android phones use micro-USB connectors whereas iPhones use Apple’s proprietary lightning connectors.

The FTC Targets Apple Music