Classifying regulations is now more confusing thanks to Biden administration

Photo Credit: Getty

Joe Biden’s Modernizing Regulatory Review executive order (E.O. 14094) raised the threshold for a “significant regulatory action” from $100 million to $200 million in “annual effect on the economy.”

These and other administration changes like the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) reworking of Circular A-4 guidance on regulatory review matter for long-term regulatory supervision as well as for approaching congressional battles over resolutions attempting to disapprove certain costly rules, particularly in environmental policy, during this last year of Biden’s four-year term.

In a CEI report on the matter, we outlined the case for Congress to scrub and simplify regulatory nomenclature that has accumulated in laws, executive orders and administrative archives.

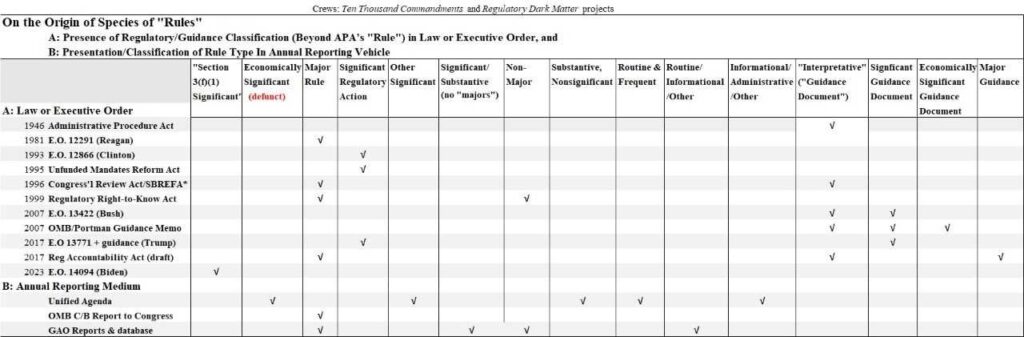

Instead of subtracting, for the moment we must now add E.O. 13094’s “Section 3(f)(1) Significant” rule designation (S3F1) to our developing taxonomy of rule types, large and small, shown nearby (and online).

Perhaps boosting our case, a recent Government Accountability Office report we described here references the heritage of certain rule types in its broader appeal for improving congressional oversight of the regulatory process.

“In the beginning,” so to speak, the 1946 Administrative Procedure Act in part codified a “rule” as “the whole or a part of an agency statement of general or particular applicability and future effect designed to implement, interpret, or prescribe law or policy.”

After a couple generations, Ronald Reagan’s 1981 E.O. 12291 isolated $100 million “major rules” for stricter review. Bill Clinton’s 1993 replacement E.O. 12866 dropped “major” and adopted the aforementioned $100 million threshold for a “significant regulatory action.” In addition to cost, Section 3(f) of the Clinton order noted that conflicts across agencies, budgetary effects of entitlements, grants fees and loans and the raising of “novel legal or policy issues” also can render regulatory actions “significant.”

Out of more than 3,000 rules each year, a few hundred get tagged “significant” for purposes of E.O. 12866 (and now 14094). The “major” designation became codified in the Congressional Review Act, which was part of the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act of 1996.

Prior to Biden’s Modernizing Regulatory Review, rules reaching the $100 million threshold were called “economically significant.” Curiously enough, that phrase appears in no law nor executive order but was a convention adopted by OMB, and widely accepted.

There are several examples of this. References to “economically significant” rules were to be found footnoted in OMB’s annual Report to Congress until their replacement by S3F1 in the February 2024 edition. The Unified Agenda of Federal Regulatory and Deregulatory Actions long itemized $100 million “economically significant” rules and noted these rules’ similarity to “major” rules, but now refers to these in the past tense. The reginfo.gov page still contains a zombie FAQ that references the now-superseded category. Finally, prior to its 2023 rewrite, the OMB’s Circular A-4 guidance on practices and procedures for regulatory analysis also referred to conducting analyses for economically significant actions.

So, to be fair, the “S3F1” addition was paired with the subtraction of economically significant rules. But the inventory of rule types is large than what many probably imagine. Joining major, significant and S3F1, lesser rule classifications deployed in federal publications and databases (and shown in our table nearby) include “other significant,” “significant/substantive,” “non-major,” “substantive, nonsignificant,” “routine & frequent,” and “routine/informational.”

Born alongside the “rule” of the Administrative Procedure Act were “statements of policy” and “interpretative” rules (a.k.a. “interpretive” rules), now often referred to as guidance documents. This “interpretative” species eventually led to “significant guidance document,” “economically significant guidance document,” and other classifications.

As the table shows, the nomenclature is substantial and rather opaque. If a rule is S3F1 significant, it is also major. Major and significant rules may or may not be S3F1 significant. New names for even bigger $500 million-dollar-plus rules have been proposed (for example, the “high-impact rule” designation of the 118th Congress’s Regulatory Accountability Act). And we would need to call the tiered rule cost categories of the ALERT Act by some moniker. Nomenclature should also better capture initiatives that are specifically deregulatory

But in better characterizing the effects or costs of rules, we can surely still streamline the categories. Rather than being endangered, invasive species of rules and regulations stand to proliferate. They could use a humane culling, while at the same time be more concretely defined to better enable governing and streamlining.

For further reading:

“On The Origin Of Species Of Federal Rules, Regulations And Guidance Documents” Forbes