Time to rip the veil of secrecy off government agencies’ in-house courts

Photo Credit: Getty

In a previous piece, we explored some of the pros and cons of administrative law courts (ALCs). These are regulatory agencies’ special in-house courts, which are not part of the independent judicial branch. This post looks at how ALCs are structured.

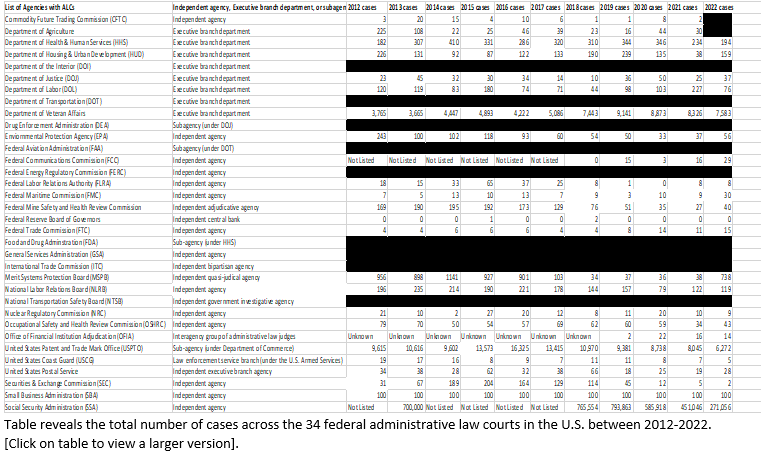

The big picture is that 34 federal agencies have ALCs. Their employees make up about a fifth of the Executive Branch, though relatively few of them are judges. ALC pay is about a third above the average for federal employees. While most ALC-possessing agencies make data about their ALC caseloads available to the public, at least a third of them keep some or all of their ALC activity hidden from public view.

Congress should pass legislation requiring better transparency and oversight for the legal arm of the administrative state. ALC transparency should be at least at the same level as standard Article III courts.

According to 2021 BLS statistics, there are a total of 13,840 administrative law judges, adjudicators, and hearing officers across the U.S. The federal executive branch has 4,460 administrative law employees, comprising 21 percent of the total workforce in the executive branch.

The hourly mean wage for federal administrative law workers is $65.98, while their yearly mean wage is $137,240. This is 36 percent greater than both the average state and local hourly rate of $42.00 and the yearly mean wage of $88,000 for administrative law employees. Administrative law court officers seem to be concentrated most heavily in the northeast region of the country, particularly in the New England area.

For context, the average salary of a federal government employee in 2021 was $93,777, which is 32 percent less than the average for federal administrative law workers.

The three states offering the largest number of administrative law court employment opportunities are California, New York, and Texas, each among the top-five most populous states. A similar trend is present for the location quotient of administrative law judges, adjudicators and hearing officers across various states, with the densest, per capita amount of ALC employees located in the New England and Mideast regions.

Among the top three states offering the highest concentration of administrative law court jobs based on state population, two of these (Connecticut and New Hampshire) are located in the New England area. The greatest number of ALC employees reside in the New York-Newark-Jersey City area, at 1,070 workers.

The top paying states for administrative law court employees are Alabama, Massachusetts, and Missouri. For the federal government employment as a whole, the most lucrative bureaucratic work opportunities tend to be in Washington D.C. High paying ALC employment, by contrast, is more decentralized.

There are only a few dozen administrative law judges in each of the 34 federal agencies that house ALCs. Among these, the Social Security Administration (SSA) houses the largest number of ALJs by far, having employed 1,400 judges in 2013 that regularly adjudicate over 700,000 cases annually.

This unusually heavy caseload was established by a controversial quota requiring each judge to process 500-700 cases a year. This has failed to address SSA’s case backlogs. Claimants wait an average of 373 days just to receive a disability hearing date. Most federal administrative law courts claim to fully adjudicate a matter in 350 days or less. SSA’s track record is a far cry from this promise.

Transparency varies widely among agencies. Among the 34 federal departments and agencies housing ALCs, 26 catalog and provide public access to their case history. Nine of these 26 agencies have online pages that provide profiles on their current judges, links for individuals to file a claim, and instructions for participating in an administrative proceeding. Despite this, these nine agencies fail to list anything about current or prior cases.

The agencies that lack an administrative case database are: The Department of the Interior (DOI), Department of Transportation (DOT), Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Food and Drug Administration (FDA), General Services Administration (GSA), International Trade Commission (ITC), and the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB).

Two of these ALCs belong to executive branch departments (DOI and DOT), three belong to sub-agencies of executive departments (DEA, FAA, and FDA), and four are in independent federal agencies (FERC, GSA, ITC, NTSB).

Four federal agencies—the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), Office of Financial Institution Adjudication, and the Social Security Administration (SSA)—have online pages that list only a limited number of cases. These ALCs only provide their adjudicative history spanning the last four or five years. This paints a very limited picture of what types of cases these select agencies have overseen and how often their ALCs process cases.

While many independent agencies are not directly accountable to the public, they are, for the most part, statutorily obligated to Congress. If a quarter of all agencies housing ALCs are allowed to adjudicate cases involving public citizens without informing the larger public about the nature of these cases, then the federal government has a major accountability probem. Why should certain federal departments and sub-agencies get a pass to keep administrative proceedings hidden from public view?

Sub-agencies like the FAA, DEA, and FDA all have bureaucratic responsibilities that fall under the executive branch, and as a result, must ultimately answer to their Cabinet department. These must regularly report their activities to the president, who is democratically accountable to the American electorate. With this understanding, administrative law courts are obligated to report adjudicative proceedings to the public, especially when such cases involve U.S. citizens and legal issues comprising public concerns.

This layered framework raises concern over the current level of bureaucratic obscurity and obfuscation. The federal executive possesses two layers of unaccountable bureaucrats (Cabinet departments and their sub-agencies) appointed by an elected official—the president. The public has a right to know why many ALCs keep their matters hidden from public view.

While public citizens are powerless to vote for or against the unelected administrative law judges overseeing these clandestine courts, they can compel them to release case information, though the process can take years and has no guarantee of success.

Under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), Americans can compel federal agencies to disclose requested information that doesn’t violate any of FOIA’s nine exemptions or three exclusions. Information requested on administrative proceedings that are partially or fully obscured by the 13 ALCs (38 percent) should not be prohibited from public view. It also should not take a FOIA request to unearth the information, especially in a country that is supposed to possess an independent judiciary and transparent executive.

Most ALCs report some information involving their annual adjudications. However, more than one-third of these courts fail to provide a full picture of their adjudicatory history. In many cases, they offer no picture.

These courts operate within a veil of secrecy as an unofficial shadow government, obscured from public view. Despite all of the BLS employment data available on ALJs, there is zero information provided on the important adjudicative matters affecting 13 federal agencies. The American public deserves to know what transpires in these in-house courts.

When we can better see the big picture of ALCs in America, we can work toward reforming them.