Tobacco 21: Feel-Good Policy Could Backfire

Amid an outbreak of “vaping-linked” lung illnesses, a campaign of fear against vaping has reached a frenzied peak. For years, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Centers for Disease Control (CDC), health groups, and lawmakers have been sounding the alarm over rising numbers of adolescents who reported using e-cigarettes once a month. The lung injuries, occurring predominantly in young people and apparently entirely related to vaping black market cannabis, has only escalated the panic. Now, many officials are jumping to support raising the minimum age for purchasing tobacco products to 21 years old as a means of addressing youth vaping. The problem, as I write in a new paper published today, is that there is little evidence raising the age limit will benefit public health. In fact, it could actually increase adolescent smoking.

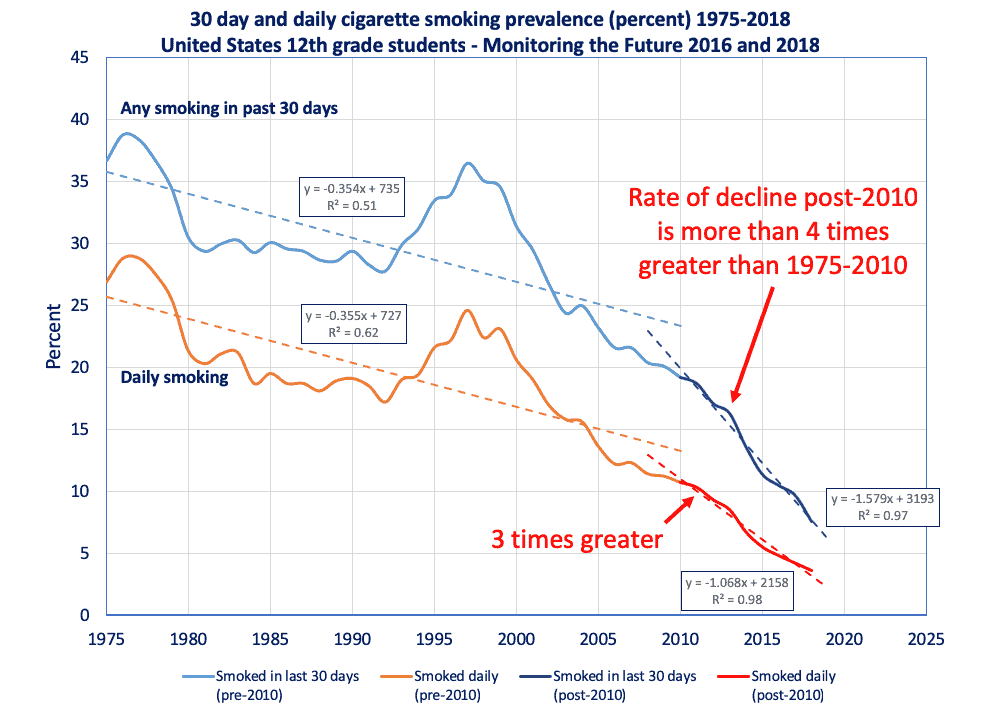

Is teen vaping is an epidemic? That is the message that FDA, CDC, and “charity” groups like the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids have been pushing since at least 2018. While it is true that surveys have found a significantly uptick in youth experimentation with e-cigarettes since 2018, the actual percent of high school-aged minors who are regularly using e-cigarettes and did not previously use combustible products is approximately half of one percent. On the other hand, the often-ignored fact is that teen smoking—the deadliest form of nicotine consumption—has been plummeting at an accelerated rate along with the increased use of e-cigarettes. In fact, teen smoking is lower than it has ever been.

Figure 1 via Clive Bates.

Those advocating for a minimum tobacco purchasing age of 21 (colloquially called “T21”) believe that doing so will cut off minors off from social sources of both cigarettes and e-cigarettes, greatly reducing the number of teenagers who start using nicotine. But, while this might seem like a common-sense initiative, there is little evidence that such a policy, especially one that applies to both combustible and non-combustible tobacco at the national level, will have the intended effect.

One of the most cited pieces of evidence for the success of T21 is the so-called “Needham miracle.” In 2005, Needham, Massachusetts became the first town in the U.S. to raise the tobacco age limit from 18 to 21. Supposedly, adolescent smoking in this town declined—much more than surrounding towns—as a result. However, if you look at the longer-term data it becomes clear that while smoking rates in Needham did decline more significantly in the first four years, after that period, decreases in smoking were significantly greater in surrounding towns than in Needham. In fact, smoking rates in Needham actually increased between 2012 and 2014. Why this would be isn’t clear and it doesn’t refute the possibility that raising the age limit to 21 could have some benefit, but it also doesn’t prove the policy’s benefits.

It is possible that what the Needham experiment actually tells us is how dangerous it is to prevent current smokers having access to e-cigarettes. The period during which data were collected in Needham overlaps with the rise in vaping that occurred after 2010. While adolescents over the age of 18 in surrounding towns had access to these lower-harm products, those in Needham did not. There is strong evidence indicating that e-cigarettes are the most effective smoking cessation tool currently available. Furthermore, there’s little dispute at this point that non-combustible nicotine is much less harmful than smoking. One would think this would warrant different rules for e-cigarettes that would make them at least as accessible as cigarettes. Sadly, that isn’t the case in the United States. Cigarettes have been and remain more available to consumers than e-cigarettes ever were. Cigarettes are sold in almost every corner store and most drug stores, making it little more than a numbers game for minors to figure out which stores won’t bother checking their ID. In Needham, it’s likely that by preventing people between 18 and 21 years old from legally accessing e-cigarettes, the 21 age limit actually discourage current smokers from switching to less harmful options, like e-cigarettes or, even worse, encouraged those not yet using nicotine to choose cigarettes instead of less-harmful vaping products.

This is speculation, of course. But, the evidence against raising the national age limit to 21 is approximately as strong as the evidence supporting it. This is not the solid ground on which national policy ought to be made, especially when we are discussing a change in the law that could affect the lifelong health of millions of adolescents. Instead of enacting feel-good legislation and patting themselves on the back for doing anything, members of Congress ought to demand more evidence before changing the law in a way that could end up backfiring and costing lives rather than saving them.