Top-down management can’t fix upcoding in Medicare Advantage

Photo Credit: Getty

Among the most consistent criticisms of the Medicare Advantage program is that private plans game the system. Over the years, policymakers have devised various fixes, but these efforts have failed and will continue to fail because they don’t change the incentives driving the behavior, they are only adding speed bumps.

This post will focus on one of these practices: upcoding, also known as coding intensity. A follow-up blog will tackle the other—favorable selection.

Coding intensity and upcoding

Unlike traditional Medicare, which pays hospitals directly for the care that beneficiaries receive, Medicare Advantage works on a “capitated” basis. Private Medicare Advantage plans get paid by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) a lump sum for every enrollee, and then the plan pays the providers for care. This creates challenges because costs among Medicare recipients vary considerably. Some people can go an entire year incurring no expenses at all, while others require continuous care.

The simplest capitation payment model would be to pay plans the average cost of all potential enrollees. Then, if the plan’s enrollment is diverse enough and representative of the entire pool of beneficiaries, the payment should be adequate. While the plan would lose money on the less healthy half, the losses would be canceled out by the healthier half.

However, because Medicare Advantage plans may not have a perfectly balanced group of enrollees, Medicare groups all the beneficiaries by their expected costs. They apportion beneficiaries into risk groups based on basic demographic information like age, sex, and their history of care. Then, the plans get paid according to the risk groups, so that a plan with higher-cost enrollees gets paid more than one with lower-cost enrollees.

Because enrollees in higher risk groups command larger payments from Medicare, plans have an incentive to ensure individual enrollees are in the highest risk group possible. Plans can accomplish this by aggressively coding health conditions, a practice known as upcoding, to bump beneficiaries into the more highly compensated group. Many have accused the plans of abusing the system by doing this.

CMS contains an entire division dedicated to reviewing Medicare Advantage contracts, and, unlike much of the rest of government, it is being expanded in the first year of the second Trump administration. This group reviews the records of Medicare Advantage beneficiaries to confirm the plans are coding accurately and not upcoding. If the audits identify a problem, they calculate the accurate payments and recover the difference from the plans.

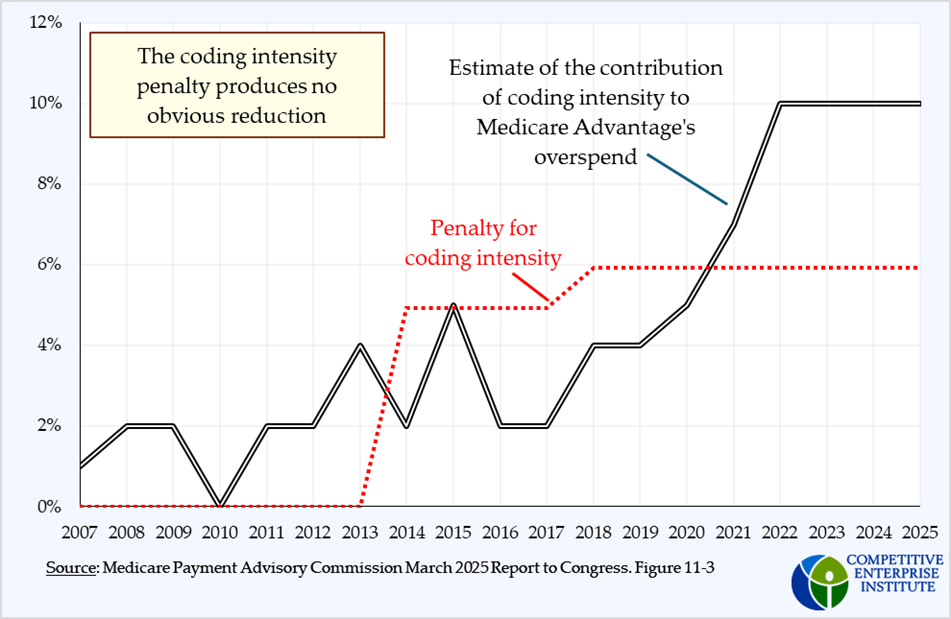

In addition to this group, which was formed in 2004, the 2005 Deficit Reduction Act called for CMS to research plans’ coding intensity more, and it resulted in the implementation of an across-the-board “coding intensity adjustment” (a reduction in payments) of 3.41 percent on all plans, regardless of actual practice, in 2010.

Over the next ten years, this adjustment rose several times. First to 4.91 percent in 2014, as required by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012, and then to 5.91 percent in 2018.

Yet despite these measures—the annual audits, the uniformly applied adjustments, modifications to the risk adjustment model itself, and regular internal analyses—the problem continues to exist and may even be getting worse, according to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC).

There’s even reason to believe that this broad, post-hoc, top-down approach is counterproductive. Studies have shown that efforts to set a universal interest rate ceiling for credit cards provide implicit permission and inducement (via a focal point for price collusion) for credit card companies that were charging lower interest to raise their rates up to the ceiling. In this case, the plans that may not have been upcoding at all will then need to expand their efforts to keep up with the other companies to stay ahead of the penalty. This phenomenon was also observed in the payday loan market.

Taken together, these facts strongly suggest that the top-down efforts to impose cost constraints are misguided, largely ineffective, and possibly even counterproductive. According to MedPAC, this problem continues to worsen, even as the effort to arrest it grows.

A subsequent blog will review another practice policymakers are trying to manage and propose a better solution.