United States, Carbon Tax Laggard?

The United States “lags” other nations’ use of carbon taxes, ClimateWire (subscription required) reports. Specifically, the United States ranks 40th out of 44 countries in a new Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) report examining each country’s combined taxes on carbon-based energy sources. Such “taxes” include cap-and-trade programs, because those policies also put an explicit price on the carbon content of fuels or emissions.

The United States “lags” other nations’ use of carbon taxes, ClimateWire (subscription required) reports. Specifically, the United States ranks 40th out of 44 countries in a new Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) report examining each country’s combined taxes on carbon-based energy sources. Such “taxes” include cap-and-trade programs, because those policies also put an explicit price on the carbon content of fuels or emissions.

“The U.S. rate was less than half the average of the 44 counties and about one-tenth the rate of the countries with the highest taxes—the Netherlands, Switzerland, Denmark and Luxembourg,” according to ClimateWire.

Well, I would put the emphasis on the other syllable. The United States ranks 4th in tax freedom to produce abundant, reliable, affordable energy from fossil fuels.

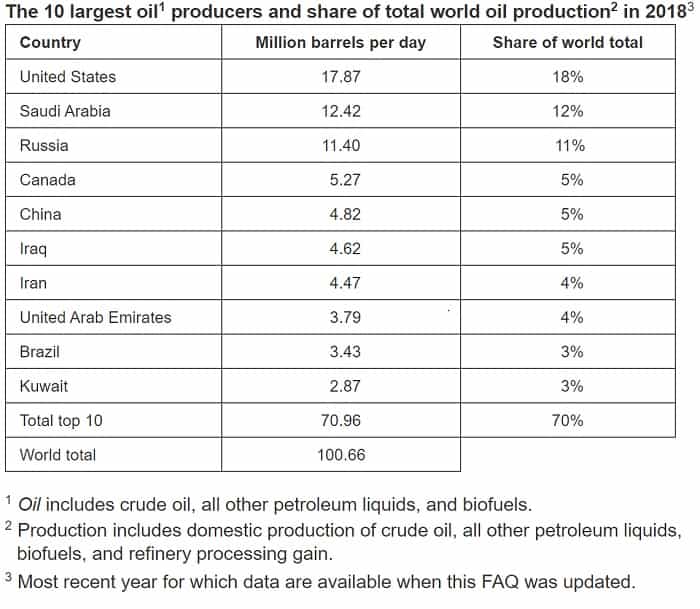

As a consequence, the United States has emerged as the world leader in hydrocarbon energy production. Examples abound. Since 2018, the United States has been the world’s top motor fuel producer, ranking ahead of Saudi Arabia and Russia.

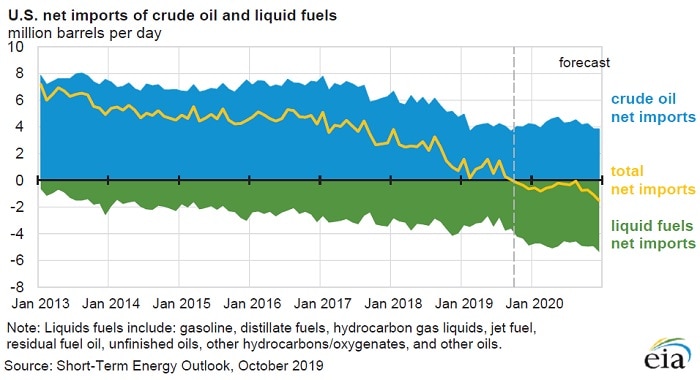

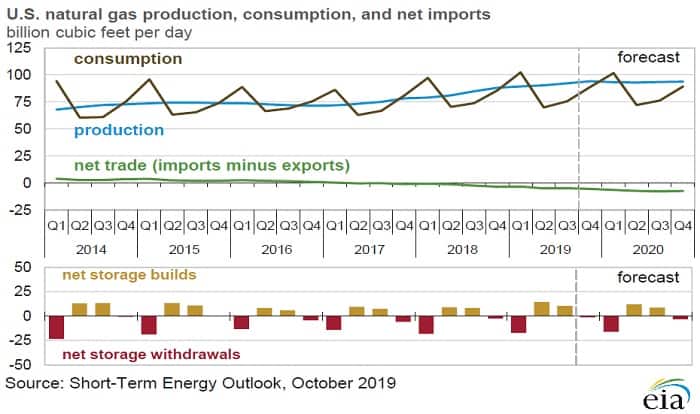

The United States is projected to be a net exporter of crude oil and other oil-based liquids by early 2020. Similarly, U.S. natural gas exports have exceeded imports since 2nd quarter 2018, and net exports are expected to keep growing through 4th quarter 2020 (the end of the forecast period).

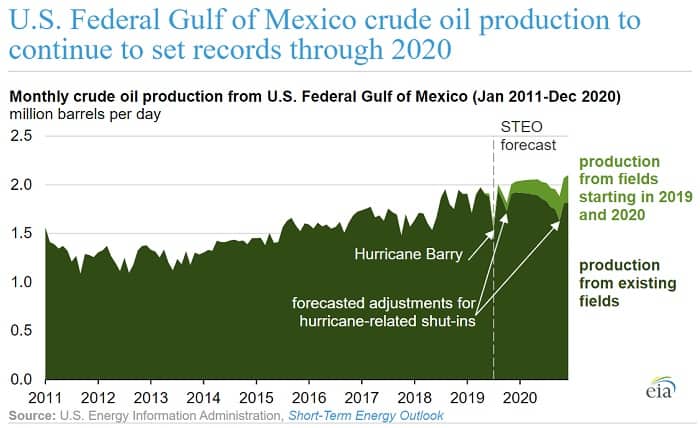

And this just in: the U.S. Energy Information Administration announced yesterday that crude oil production in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico “averaged 1.8 million barrels per day (b/d) in 2018, setting a new annual record,” and is expected “to set new production records in 2019 and in 2020, even after accounting for shut-ins related to Hurricane Barry in July 2019 and including forecasted adjustments for hurricane-related shut-ins for the remainder of 2019 and for 2020.”

Domestic hydrocarbon producers are making substantial contributions to U.S. GDP growth, job creation, consumer energy savings, manufacturing competitiveness, and geopolitical influence. All of that would be put in peril the moment Washington policymakers signal their intent to enact a carbon tax.

To be sure, the tax would likely start out small, but all carbon tax schemes ratchet up by design. Moreover, “social justice warriors” and “climate warriors”—often the same people—would continually lobby to make the tax more punitive, both to fund massive new federal programs and bankrupt the coal, gas, and oil industries.

As the ClimateWire article helpfully points out, “A Treasury Department report in January 2017 found that a tax of $49 per ton of CO2 emissions would generate roughly $200 billion a year in tax revenue.” A member of Congress must be mighty principled not to slabber at the prospect of squeezing an extra trillion dollars out of the private sector in just five years.

Two points are often forgotten in such discussions. First, the power to tax involves the power to destroy, and never more so than in the case of a carbon tax. That’s because unlike other taxes, a carbon tax is designed to tax away the base on which it is levied. Second, by subjecting carbon-intensive industries to new levels of political risk, a carbon tax can drive capital out of the targeted firms long before the carbon penalty itself renders them uncompetitive.

Although the full OECD report is behind a paywall, the executive summary is posted online. One of its claims—a staple of carbon tax advocacy—deserves a response: “Increasing carbon prices first where they currently are lowest makes sense. Coal is a particularly striking case in point as it is presently taxed at some of the lowest rates across all energy users despite its harmful climate and air pollution impacts.”

In the United States, coal is subjected to manifold implicit carbon taxes in the form of renewable electricity mandates, which increasingly mark off segments of the market in which coal is forbidden to compete, federal and state environmental controls, which impose billions of dollars in compliance costs on coal mining and combustion, and unlawful state-level restrictions on coal exports. At the same time, Congress keeps renewing tax credits that subsidize wind and solar power at the expense of coal.

To be sure, the Trump administration has rescinded the prior administration’s so-called Clean Power Plan and other federal regulatory components of the war on coal. However, every Democratic presidential candidate has vowed to repeal the Trump rollback, so coal remains under high levels of political risk.

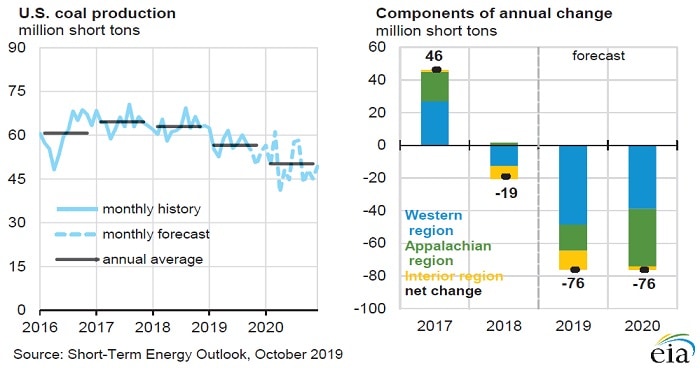

In any event, due to the combination of cheap gas, environmental compliance costs, renewable energy quota, and political risk, U.S. coal production continues to decline from 2011 levels. So even if one assumes reducing coal consumption should be a goal of U.S. policy, a carbon tax is not needed to achieve it.