Will EPA empower California to ban gasoline-powered cars?

Photo Credit: Getty

Did Congress authorize the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to outlaw the sale of new internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles? Did it authorize the EPA to delegate such power to California? No and no.

Yet the EPA is widely expected to greenlight California’s zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) mandates, which progressively restrict the sale of new gasoline- and diesel-powered vehicles in the state, culminating in a 100-percent ban by 2035, enforced in perpetuity.

In more technical terms, the EPA is expected to grant California a waiver of federal preemption under Section 209(b) of the Clean Air Act (CAA), allowing the State to implement its Advanced Clean Cars II (ACC II) program. The ACC program includes California’s ZEV sales mandates, motor vehicle greenhouse gas (GHG) emission standards, and tailpipe standards for conventional air pollutants.

By “zero emission vehicle,” California means an electric vehicle (EV) powered by either batteries or fuel cells. The vast majority of EVs produced today are battery-powered.

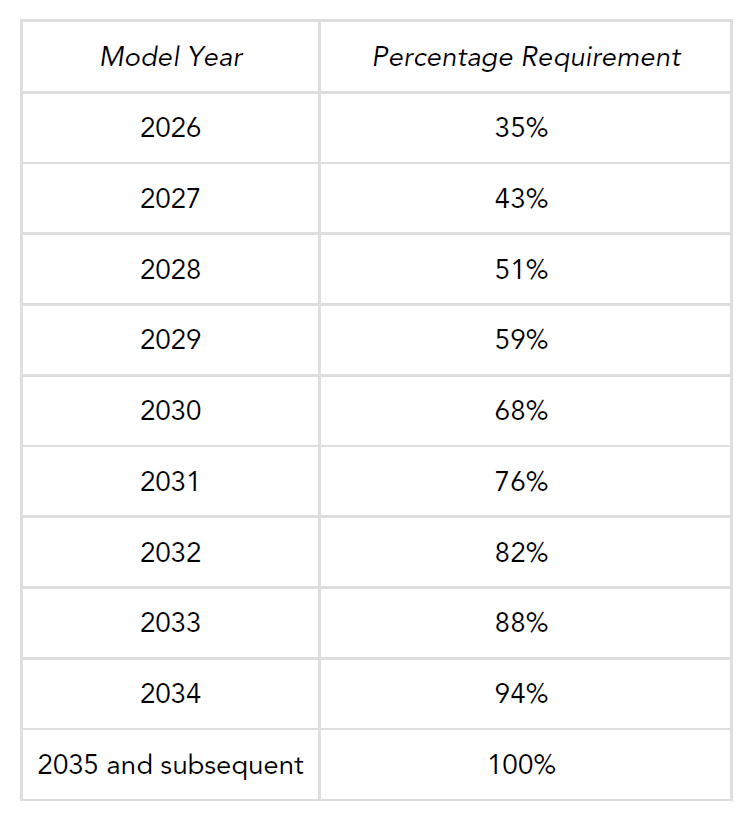

California’s ZEV mandates are requirements to sell specified quantities of ZEVs as a percentage of total annual sales. Under the existing ACC I program, approved by the EPA in January 2013, and reinstated in March 2022, required ZEV sales increase from 2 percent of total sales in 2018 to 16 percent in 2025. Under ACC II, required ZEV sales increase from 35 percent of total sales in 2026 to 100 percent in 2035.

Figure Source: California Air Resources Board, ACC II Waiver Request Support Document

Consumer alert!

If approved and implemented, the ACC II ZEV program will have nationwide market impacts. Under the EPA’s current interpretation of CAA Section 177, other states may adopt and enforce California’s ZEV mandates once the agency has granted a 209(b) waiver for the ACC II program. Rhode Island, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Virginia, and Washington state have enacted laws to implement the ACC II ZEV program. New Jersey’s environmental agency has issued a regulation to do so.

Moreover, in May 2023, the EPA proposed tailpipe carbon dioxide (CO2) standards that effectively require two-thirds of all new light-duty vehicles sold to be ZEVs by 2032. One of the proposal’s key policy rationales is that state ZEV mandates will electrify vehicle markets anyway. Of course, states can only do that if the EPA empowers them to do so.

These developments portend a massive rollback in consumer freedom and substantial losses in consumer welfare. Electric vehicles (EVs) have significant downsides including: higher purchase price, reduced range, long recharging times, scarce charging infrastructure, reduced towing capacity, impaired cold weather performance, and less reliability during blackouts from natural disasters.

Millions of middle-income households are already priced out of the market for new motor vehicles. The regulatory vehicle electrification agenda will constrain many Americans to purchase EVs they cannot afford or do not want, or give up on personal automobility altogether. Households forced to rely on transit could experience significant losses of personal liberty, time, convenience, economic opportunity, and health.

The EPA invited public comment on California’s ACC II waiver request in December 2023. The comment period closed last week. For an in-depth analysis of all the major issues, take a look at the comments submitted by Marc Marie of the Center for Environmental Accountability (CEA).

I submitted comments as well, emphasizing two points. First, Section 32919(a) of the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA) preempts California’s ZEV program and tailpipe GHG emission standards.

Second, contrary to the EPA’s insinuation, House committee report language asserting California’s “broadest possible discretion” does not mean CAA 209(b) implicitly repeals EPCA preemption. Nor do two D.C. Circuit decisions quoting that language declare California to be the nation’s automotive industrial policy czar. CAA report language does not trump EPCA statutory language. Moreover, the California policies actually upheld by the court were narrow, not broad, acts of discretion.

EPCA preemption

Prior to considering California’s ACC II waiver request, the EPA and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) had to repeal Part 1 of the September 2019 Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient Vehicles Rule (SAFE 1).

In SAFE 1, NHTSA determined that EPCA 32919(a) preempts California’s tailpipe GHG standards and ZEV mandates, rendering them null and void. The EPA, for its part, revoked the 2013 ACC I waiver authorizing California to implement those policies.

NHTSA repealed its portion of SAFE 1 in December 2021. The EPA repealed its portion in March 2022, and in the same action reinstated the ACC I waiver.

Not even once in their combined SAFE 1 repeal actions (totaling 103 pages in the Federal Register) did the agencies attempt to rebut SAFE 1’s EPCA preemption analysis. Indeed, they do not even summarize it. That is not surprising. The EPCA preemption analysis has the clarity and rigor of a proof in geometry.

Here is the concise ECPA preemption analysis that neither agency confronts:

- EPCA 32919(a) prohibits states from adopting or enforcing laws or regulations “related to” fuel economy standards. California’s tailpipe carbon dioxide (CO2) emission standards are physically and mathematically “related to” fuel economy standards. An automobile’s CO2 emissions per mile are directly proportional to its fuel consumption per mile. If an agency regulates tailpipe CO2 emissions, it also regulates fuel economy, and vice versa.

- The Congress that enacted EPCA in 1975 understood the scientific relationship between CO2 emissions and fuel economy. That is why Congress directed the Department of Transportation to use the EPA’s fuel economy calculation and testing procedure, which is to measure tailpipe emissions of CO2 and other hydrocarbons (EPCA Section 503(d)(1)).

- California’s ZEV mandates are substantially “related to” fleet-average fuel economy standards. As ZEV mandates tighten, and EV market share increases, fleet average fuel economy eventually increases. Conversely, as the EPA’s recently proposed tailpipe CO2 standards show, if fuel economy requirements tighten beyond a certain point, manufacturers must sell more EVs and fewer ICE vehicles to comply.

- Because state policies regulating or prohibiting tailpipe CO2 emissions are directly or substantially “related to” fuel economy standards, they are preempted—rendered null and void.

- Preemption statutes derive their authority from the Constitution’s Supremacy Clause (Maryland v. Louisiana, 1981). Preemption occurs ab initio—at the moment a conflicting state policy is enacted or adopted, not when a court later declares it so (Cabazon Band of Mission Ind. v. City of Indio, 1982).

- Thus, the EPA cannot legalize California’s tailpipe GHG and ZEV standards by waiving Clean Air Act preemption. EPCA preemption is non-waivable, and it voided those policies before the EPA agreed to review them. California’s tailpipe GHG and ZEV standards are legal phantoms—mere proposals without force or effect.

The EPA and NHTSA’s mum’s-the-word response to SAFE 1’s EPCA preemption analysis “entirely fail[s] to consider an important aspect of the problem,” rendering their repeal actions arbitrary and capricious.

CAA report language does not trump EPCA preemption

The EPA’s March 2022 Reinstatement of the ACC I waiver repeatedly affirms that Congress revised CAA 209(b) in the 1977 Clean Air Act Amendments to “afford California the broadest possible discretion in selecting the best possible means to protect the health of its citizens and the public welfare.” The Reinstatement quotes that phrase, in whole or part, 11 times. CARB’s ACC II waiver request support document similarly contends that Congress gave California “the broadest possible discretion in reducing air pollution and its impacts.”

The Reinstatement also repeatedly cites two cases where the D.C. Circuit affirmed California’s “broadest possible discretion”: Ford Motor Co. v. EPA (1979) and Motor and Equipment Mfrs. Ass’n, v. EPA (1979) (MEMA I).

The reader is left with the impression that, whatever SAFE 1’s EPCA preemption argument might be, it cannot possibly be correct, because it conflicts with the “broadest possible discretion” California enjoys under CAA 209(b).

In effect, the EPA treats CAA 209(b) as implicitly repealing EPCA 32919(a), although without acknowledging or defending that position.

That interpretation of CAA 209(b) does not survive inspection. Both the policy significance of “broadest possible discretion” and the precedential force of the D.C. Circuit’s decisions are less than the EPA suggests.

In the first place, the phrase “broadest possible discretion” is nowhere to be found in CAA 209. It comes from the House committee report on the 1977 Clean Air Act Amendments.

Late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia famously cautioned against elevating report language above statutory text as a guide to interpreting the law. Judges are not mind readers. Report language and other forms of “legislative history” are at best uncertain guides to congressional intent. Worse, commentary by lawmakers on their own handiwork may not be free of bias or exaggeration, especially when the legislation falls short of the drafter’s policy ambitions. In short, report language may spin rather than clarify the statute’s meaning.

Let’s now compare CAA section 209(b) and EPCA 39219(a). Whereas 209(b) affords California the “broadest possible discretion” according to report language, EPCA 32919(a) contains the broadest possible preemption—applying to any state law or regulation “related to” fuel economy standards—according to the text of the statute itself.

To implicitly repeal EPCA 32919(a), CAA 209(b) would not only have to include the “broadest possible discretion” language, it would also need to include the phrase “notwithstanding any other provision of law.” It does neither.

Finally, let’s look at the California policies the D.C. Circuit approved while invoking the “broadest possible discretion” report language. MEMA I upheld CARB’s discretion to limit the amount of maintenance manufacturers may require of vehicle purchasers to maintain vehicle warranties. CARB’s goal was to “encourage” manufacturers to build more durable emission control equipment.

In Ford Motor, the D.C. Circuit upheld CARB’s discretion to adopt weaker-than-federal carbon monoxide (CO) standards in order to implement stronger-than-federal oxides of nitrogen (NOX) standards. According to CARB, NOX pollution was the bigger problem in California, and it might be technologically difficult to meet both the State’s desired NOX standard and the federal CO standard. Thus, CARB concluded, the EPA may waive preemption for those changes because CAA 209(b) allows California to have its own standards as long as such standards “in the aggregate” are as protective as federal standards.

So, while reciting the “broadest possible discretion” language, the actual discretion approved by the court was narrow—prudential adjustments to industry practice and federal policy. MEMA I and Ford Motor do not come close to authorizing California to redirect national policy or reorganize an industrial sector.

Conclusion

In West Virginia v. EPA (2022), the Supreme Court struck down the EPA’s so-called Clean Power Plan as an attempt to settle a major question of national policy—whether coal powerplants should be allowed to exist—without a clear congressional authorization in the CPP’s putative statutory basis, CAA Section 111(d).

The EPA now undertakes, again without clear statutory authorization, to settle another major question of national policy—whether production and sale of new ICE vehicles should be banned. At a minimum, the EPA is trying to severely limit the availability of ICE vehicles.

If Congress wanted the EPA to start forcing ICE vehicles off the road, then it would have said so. It did not.

I make no predictions as to how courts or the next administration and Congress will resolve these issues.