Perverse Psychology

How Anti-Vaping Campaigners Created the Youth Vaping “Epidemic”

Executive Summary

Cigarette smoking is a lethal habit that kills approximately half of those who sustain it over their lifetime. But, contrary to popular belief, the nicotine in cigarettes does not contribute significantly to this death toll. Combustion, the burning of materials, produces the vast majority of toxic chemicals, which, when inhaled repeatedly and over many years, leads to the death and disease associated with smoking. If smokers could switch to a product that delivers nicotine without combustion, they would eliminate most of the risk associated with tobacco use.

Such products exist, in the form of nicotine replacement therapies, like patches, gums, and lozenges. But these have proven largely ineffective for long-term smoking cessation. Meanwhile, electronic nicotine delivery systems, known as e-cigarettes, appear to be at least twice as effective in helping smokers quit and remain smoke-free. This is likely because, unlike other cessation tools, e-cigarettes satisfy not just cravings for nicotine, but other behavioral and psychosocial benefits smokers associate with smoking.

E-cigarettes—a substitute for combustible cigarettes that is orders of magnitude safer than smoking and that smokers will find appealing—have the potential to save and improve billions of lives over the next century. Countries that have embraced these harm- reducing alternatives are already reaping the benefits through accelerating declines in smoking, smoking- related illness, and death. The United States, unfortunately, is not one of them.

Evidence from researchers around the world underscores the prospect that e-cigarettes are the greatest public health opportunity in a generation. Yet, anti-tobacco advocates have only intensified efforts to malign and prohibit these potentially lifesaving products.

At first, they cited a lack of evidence about their safety as justification for restricting their availability. After the relative safety of the products was confirmed by repeated observational and toxicological studies, they pivoted to the argument that even if e-cigarettes are less harmful than smoking, they are ineffective for smoking cessation. That too proved specious, with e-cigarettes contributing to accelerated declines in smoking and a smoking rate that is now lower than it has ever been in recorded history.

Unable to legitimize their agenda with scientific evidence, those seeking to eradicate e-cigarettes have turned to that last resort into which all moral crusades invariably retreat: fear over child welfare.

As early as 2013, groups dedicated to eliminating all use of tobacco have alleged that e-cigarettes were merely a ploy devised by “Big Tobacco” to reverse the trend away from smoking and attract youth into nicotine addiction and eventually smoking. This rhetoric became a central theme of anti-vaping advocacy, even as adolescent use of e-cigarettes declined dramatically in the following years. By 2016 a vast network of government agencies, charities, and health organizations successfully endeavored to foment public anxiety over youth vaping. This culminated with the 2018 announcement by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that youth vaping was not just an issue of concern, but an “epidemic.” The evidence indicated that the number of youths using e-cigarettes habitually who had never smoked tobacco was minimal, yet the announcement ignited widespread moral panic that persists to this day.

The tactic of using concern for child welfare as a smokescreen for abstinence-only policies is not new. It was employed by the temperance movement to prohibit alcohol and utilized to justify the war on drugs, as well as to block efforts to replace criminalization with treatment. Like those efforts, the anti-vaping messaging blitz succeeded in convincing many of the threat e-cigarettes supposedly pose to adolescents’ health.

Federal agencies have taken steps to rein in the vaping market and raise the minimum age for purchasing tobacco products, including e-cigarettes, to 21.

Congress has held dozens of hearings and introduced multiple bills, while state authorities across the country have taken steps toward banning most e-cigarette products, with various degrees of success. Yet, none of this has stopped adolescents from using e-cigarettes.

Since the initiation of this war on e-cigarettes, youth interest in vaping, including the vaping of nicotine, non-nicotine, and cannabis derivatives, has surged. Rather than ask why this might have happened—after years of waning youth interest in e-cigarettes and in spite of increasingly omnipresent warnings against using e-cigarettes—advocates blamed the vaping industry. They have asserted that the popularity of Juul, the availability of supposedly “kid-friendly” flavors, and unscrupulous advertising by the vapor industry has caused this uptick, and held this up as evidence for the need to increase funding to anti- vaping efforts, raise taxes on vapor products, and impose restrictions on the market even more onerous than those faced by traditional tobacco.

But, as this paper seeks to demonstrate, it was not the vapor industry that reignited youth interest in vaping; it was anti-vaping advocacy. Evidence from developmental psychology, the determinants that push youth toward risky behaviors, and the reasons public messaging campaigns can backfire all indicate that the most viable explanation is not that more youths began vaping in spite of anti-vaping campaigns, but because of them. Therefore, devoting even more money and attention to anti-vaping campaigns is unlikely to solve the issue of youth vaping. More likely, it will make the problem, insomuch that there is a problem, worse.

Introduction

Alcohol prohibition has been deservedly confined to the dustbin of history, but prohibitionist strategies have persisted largely unchanged since the days of demon rum and reefer madness. Modern neo-puritan activists hoping to eliminate “sinful” behaviors continue to promote the debunked gateway theory, conflate any use with addiction or abuse, and vilify all who oppose their objective of social purity.1 Even as modern societies increasingly recognize the dire consequences of alcohol prohibition and marijuana criminaliza- tion and attempt to rectify those failures, many advocates seek to launch a new drug war. The tobacco control movement, once dedicated to reducing the death and disease caused by smoking, has expanded its mission to eliminating all nicotine use.

Despite the evidence that vaping is a significantly lower-risk way to consume nicotine, the movement is now myopically focused one-cigarettes, employing the same arguments and methods of drug warriors of the past. Yet, the most valuable tactic these anti-vaping advocates inherited from their prohibitionist forebears is the exploitation of justifiable concern for children to advance their political agenda.

Under the guise of protecting the next generation from addiction, government agencies have waged a publicity offensive against e-cigarettes since at least 2015, supported by a panoply of public health advocacy groups they fund. The more the scientific evidence proved e-cigarettes to be a relatively safe way to consume nicotine— especially in comparison with combustible cigarettes—and thus a potentially life-saving technology for the millions of adult smokers around the world, the more anti-tobacco rhetoric has focused on the threat vaping poses to adolescents’ well-being.2

The rhetorical escalation peaked in 2018, with the introduction of the idea that youth vaping had reached “epidemic” levels—a theme that has dominated the discussion about e-cigarettes since.

The fact is that there is no epidemic, a term defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as “an increase, often sudden, in the number of cases of a disease above what is normally expected in that population in that area.”3 Considering that only a tiny percentage of American teens report vaping habitually, and that there is no disease linked with vaping nicotine e-cigarettes, this is not an epidemic.4 There is, however, a recent upward spike in experimentation.

Based on annual survey data, the number of American middle and high school students who report vaping at least once in the last month has risen sharply since 2018.

Concern—not panic—about this unexpected uptick in youth vaping was warranted. However, even before the availability of data that supposedly indicated a youth vaping “epidemic,” the panic was already underway. The previous two national surveys for 2016 and 2017 showed that youth experi- mentation was actually declining. The number of high school students who reported any e-cigarette use in the last month, in fact, declined nearly 30 percent between 2015 and 2016. During the same time period, the industry was also in the process of moderating its practices in response to concerns about youth use among the public and regulators. Yet, this good news did not deter anti-tobacco groups from launching their multi-million- dollar anti-vaping campaigns.

Over the following years, consumers were inundated with commercials, health agency warnings, and news media horror stories about the dangers of youth e-cigarette use. It was following this wave of alarmism that youth experimentation with vaping spiked once again.

Instead of reflecting on the possible explanations for why youth vaping would rise along with increasing scrutiny, public pressure, and industry action to restrict youth access, anti-tobacco groups blamed Juul, the most popular e-cigarette, and the vaping industry for intentionally targeting their products at adolescents. But it was not “kid friendly” flavors or predatory marketing by the e-cigarette industry that reignited youth interest in vaping—it was anti-vaping advocacy.

The Rise of the E-cigarette “Epidemic”

Electronic nicotine delivery devices (ENDS) first appeared on the U.S. market in 2007. Like most successful products, their introduction was followed by a period of gradually increasing consumer interest, more entrants into the market, more competition and variety, and an apparent burst of popularity. Among adults, e-cigarette use nearly doubled between 2010 and 2013 (from 0.3 percent to 0.5 percent).5 Adolescent use of e-cigarettes followed a similar pattern, tripling between 2011 and 2013 (from 1.5 percent to 4.5 percent).6 But, while adults continued to adopt e-cigarettes in steadily growing numbers, use among adolescents surged.

The number of high school students who reported vaping at least once in the past month jumped by more than 2,500 percent between 2013 and 2015 (from 0.6 to 16 percent, respectively), according to data from the National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS), an annual survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).7 While this provoked concern, it did not ignite an all-out panic.

Many pointed out that the survey merely indicated past month use, one-off experimentation by adolescents, and not necessarily habitual use and dependence. Furthermore, the survey does not differentiate between the many different things that these adolescents could be vaping, such as marijuana and other non-nicotine products.

Fortunately, like most fads, vaping soon fell out of favor with teenagers. By 2016, the rate of high school students reporting any past-month use of e-cigarettes plummeted by 30 percent and held steady the following year, at just 11.7 percent.8 Yet, it was in that year that the idea of a youth vaping “epidemic” emerged.9

Figure 1. High School Student Use, National Youth Tobacco Survey

In September 2018 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) declared there was a youth vaping epidemic and launched a media campaign to discourage youth use.

In many respects, the FDA was a latecomer in embracing the e-cigarette hysteria. A few advocacy groups, like the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, had been fomenting panic about adolescent e-cigarette use since at least 2013, with most other members of the tobacco control establishment joining in by 2017.10 But the participation of the FDA, as the body with regulatory authority over the industry, in the war against vaping gained anti- tobacco advocates bountiful funding and news media attention.

Like its non-governmental partners, the FDA blamed the upsurge in youth vaping primarily on one company: Juul.11 According to anti-vaping advocates, Juul lured teenagers to its product with concentrated nicotine, sweet flavors, and sleek design, which made it easy to hide from parents and teachers.12 However, the FDA’s assertion does not withstand scrutiny.

Blame Game: Crown Juul

Owned originally by the Silicon Valley startup, Pax Labs, Juul began marketing its e-cigarette in June 2015.13 Coincidentally, its launch occurred just after data collection ended for that year’s edition of the National Youth Tobacco Survey. Based solely on this survey data, Juul’s presence on the market—at least initially—had no effect on youth vaping rates. In fact, in 2016 high school vaping declined by 30 percent.14 The following year, it remained practically the same. Yet, despite Juul coming to market before this decline, anti-vaping advocates still pointed to it as the cause of youth e-cigarette use.

There is no denying that there is, or at least was, something different about Juul that fueled its growing popularity. While the company had just 2 percent of e-cigarette sales in 2016, by December 2017 it had claimed 30 percent of that market.15 Its rise only accelerated after Juul Labs separated from parent company Pax Labs in 2018; by January of the following year Juul claimed a 70 percent share of the e-cigarette market.16

When youth vaping rates increased in 2018, anti-vaping advocates blamed Juul, which had been on the market for three years. They asserted that its sleek and discreet design, high nicotine content, and “kid friendly” flavors were uniquely appealing to adolescents.17 Yet, by 2018 there was nothing particularly unusual about the Juul device. Its size, shape, and functionality are similar to most pod-based e-cigarettes—something even outspoken anti-vaping advocates admitted in August 2018 when they petitioned FDA to address the “numerous” Juul knockoffs on the market.18

Advocacy groups like the Truth Initia- tive and the Campaign for Tobacco- Free Kids popularized the talking point that Juul pods contained extremely high levels of nicotine—as much as a whole pack of cigarettes.19 At 59 mg/mL, they are correct that Juul contains more nicotine than most, if not all, other pod-based e-cigarettes.

But many e-liquids (used with refillable devices) come in similar concentrations, with 50 mg/mL being a common strength offered by companies.20 Furthermore, the point is that a single pod contains an amount of nicotine similar to a pack of cigarettes; a single pod is meant to be consumed over the same period of time it would have taken the user to smoke a pack of cigarettes.

What set Juul apart, at least in the beginning, was not so much the amount of nicotine in each pod, but its patented nicotine formula. At the time of its launch, Juul was the first on the retail market to use “nicotine salt.” This novel formula differed from the traditional e-liquids, which use “freebase” nicotine, allowing users to inhale higher concentrations of nicotine without a harsh effect on the throat. More importantly, nicotine salts are absorbed in a way that more closely mimics the nicotine-absorption experience of traditional cigarettes.21

While critics claim the use of nicotine salts is what makes Juul an addiction risk for adolescents, it also explains why adult smokers often find Juul more satisfying than other e-cigarettes and why, as a result, it is a more acceptable replacement for those looking to quit smoking. Furthermore, while Juul might have been the first to use nicotine salts, by 2018, when youth vaping surged, it had many nicotine salt competitors hoping to replicate its success.22 As of 2019, there are countless brands of e-liquid available in nicotine salt formulations. However, Juul’s design and even its nicotine have received far less attention than its other supposedly youth-appealing feature: flavors.23

“Only Children Like Flavor” From the beginning of the youth vaping panic, the most persistent talking point and political target has been the availability of e-cigarettes in flavors other than tobacco.24

Throughout legislative hearings, press conferences, and academic presentations, tobacco opponents have cited the existence of flavors like “bubblegum,” “unicorn poop,” and even mint as evidence proof that e-cigarette companies target their products at minors. For example, the California Department of Public Health’s (CDPH) “Flavors Hook Kids” campaign centered on the idea that youth vaping rates can be explained almost entirely by the existence of fruit, candy, and dessert-flavored e-cigarettes.25 Consequently, CDPH has sought to ban flavors as a means of ending the youth vaping “epidemic.”

In one way, critics are correct that a variety of tasty flavors is part of the advantage e-cigarettes have over other products. Unlike gums, patches, or pills, e-cigarettes provide users with the chemical sensations of nicotine and other sensory pleasures. And it is one reason that e-cigarettes are more effective than other smoking-cessation methods. Research finds that non-tobacco flavors are a critical element in inspiring smokers to try the harm-reducing alternative and, more importantly, in helping those who have switched from cigarettes to e-cigarettes to stick with it instead of relapsing back to smoking. For example, in 2018 researchers at the University of Kentucky found that adults over 25 prefer sweet flavors and that this preference becomes more likely the longer one has been vaping.26

Figure 2. Nicotine Levels over Time, in Minutes

Image via Juul Patent https://www.vapor4life.com/blog/the-truth-and-technology-behind-juul-and-nic-salts-revealed/ and bit.ly/2DRlycq

Furthermore, surveys of adult e-cigarette users find that the variety in flavors e-cigarette users is independently associated with smoking cessation success.27 This may be due to the disassociation of nicotine from the smell and taste of tobacco. As a team of British researchers found in a 2018 study, e-cigarette users reported that temporary relapse back to smoking was perceived as negative and distasteful compared with the experience of vaping, reinforcing their commitment to stick with vaping as a mode of smoking cessation.28

For non-smokers, however, there is scant evidence that flavors play a significant role in whether they try or continue to use e-cigarettes.29 Thus, flavors alone cannot explain e-cigarettes’ appeal to adolescents. Food stores have shelves packed with sweet and savory snacks, almost any of which would be cheaper, easier, and legal for teenagers to purchase. Liquor stores, too, carry an increasing variety of alcoholic beverages flavored with chocolate, spices, fruits, and other sweet ingredients, yet there has been no uptick in youth drinking—quite the opposite, in fact.30

Still, the claim that flavors attract adolescents to e-cigarettes has proved convincing for many lawmakers, regulators, and funders, like former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg who recently pledged $160 million to groups pursuing flavor bans.31

Figure 3. Current Cigarette Smoking among U.S. High School Students

U.S. Food and Drug Administration, “Trump Administration Combating Epidemic of Youth

E-Cigarette Use with Plan to Clear Market of Unauthorized, Non-Tobacco-Flavored E-Cigarette Products,” news release, September 11, 2019,

https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/trump-administration-combating-epidemic-youth- e-cigarette-use-plan-clear-market-unauthorized-non.

Though their initial focus was on candy and dessert-like flavors, anti-vaping advocates have recently shifted their focus from dessert- and candy-flavored e-cigarettes to the flavors commonly enjoyed by adult smokers: mint and menthol.32 This change in strategy may reflect advocates’ tacit recognition that non-tobacco flavors are not the driving factor behind youth vaping.

The good news, rarely reported, is that the youth smoking rate is now lower than it has ever been, with less than 6 percent of high school students categorized as current cigarette smokers in 2019.33 This tremendous achievement is thanks, in no small part, to the same anti-tobacco advocates and public health advocates who, since at least the 1970s, endeavored to educate the public about the dangers of smoking. However, despite their efforts and early success, which contributed to major reductions in smoking throughout that decade and the next, in the 1990s youth smoking surged. It peaked around 1997 at nearly 40 percent before reversing into a decline that has continued until today.34 It is worth noting that this surge, peak, and decline all occurred before tobacco companies introduced flavored cigarettes.35

Prior to 1999, teenage smokers had functionally only two options: tobacco and menthol. In that year, however, three major tobacco companies began marketing candy, fruit, and alcohol- flavored cigarettes. Still, the availabil- ity of these “kid friendly” flavored cigarettes had seemingly no effect on youth smoking, which began its dramatic and relatively steady decline after 1997 and through 2006, when political pressure forced tobacco companies to discontinue those flavors.36 In November 2018, political pressure prompted Juul to remove all but three of its flavors from the retail market—leaving tobacco, menthol, and mint—and halt all social media promotion.37

As with combustible cigarettes, the introduction and removal of Juul flavors appears to have zero correlation with adolescent use. And the company’s attempt to quell the public wrath, which by then was targeted almost exclusively at Juul, proved futile. As the 2019 National Youth Tobacco Survey (data for which was collected after Juul withdrew most of its flavored pods from retail) shows, past-month vaping among middle and high school students only increased.38

It is possible that, despite removing flavors from the retail market, youth were still able to obtain flavored Juul pods online or through social sources.39 Anti-tobacco advocates also argue that adolescents switched or continued to use the company’s mint and menthol pods.40 Banning all but tobacco, they argue, is the only solution. But, the 2019 NYTS points to a different cause that explains the recent uptick in youth vaping: marketing.

Many have accused Juul of taking a page out of Big Tobacco’s playbook by using colorful packaging, social media “influencers,” and attractive models to stealthily market their products to youth.41 Whether such claims were true or untrue, the attention of regulators, lawmakers, and the public forced the company to radically tone down its advertising. By 2018, Juul’s advertisements featured only individuals who were obviously well into their adult years, and the company completely eliminated its social media presence. Yet, Juul also no longer needed to spend millions advertising its products because anti-vaping groups began doing it for them. And it was the same Big Tobacco tactics that health departments and medical groups employed to market their message to youth.

Tobacco companies learned long ago that telling adolescents that cigarettes are dangerous and only for adults does not discourage youth smoking. In fact, attempts to persuade teenagers not to do something appears to be among the most effective ways to pique their interest in that activity.42 And, beginning in earnest in 2015, anti-vaping campaigns spent billions doing precisely that. It was this bar- rage of anti-vaping messaging, not flavors, high nicotine, Juul, or Big Tobacco, that reignited youth interest in vaping.

Make Vaping Cool Again

Public concern about teen e-cigarette use grew slowly but steadily in the years after e-cigarettes first appeared on the U.S. market. Then, in 2018, this concern evolved into an all-out moral panic. On September 11, 2018, then- FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb announced that youth vaping had become an “epidemic”—a determination he supposedly made after reviewing the preliminary 2018 National Youth Tobacco Survey data. This data revealed that, after two years of declines, vaping among high school students had jumped by a shocking 78 percent in a single year.73 Even though only 0.6 percent of high school students who had never smoked reported habitual vaping (≥20 days in the past month), the announcement galvanized the anti-smoking community.44

The FDA’s declaration of youth vaping as an “epidemic” gave legitimacy to crusaders who had long warned of a crisis. This set the stage for the agency to turn its anti-tobacco efforts toward vaping (though FDA had incorporated anti-vaping themes as early as 2016). It also ensured a steady stream of funding for existing and new efforts to combat adolescent vaping, including the FDA’s own “Epidemic” campaign, unveiled to the public the week of Gottlieb’s announcement.45 The FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) produced a marketing campaign to warn teenagers against e-cigarettes.46 The inaugural commercial in that initiative aired just six days after Gottlieb’s announcement and was produced by a New York ad firm with which CTP had signed a $625 million five-year contract the previous year.47 According to the FDA’s analysis, 12-17 year-olds would be exposed to the Epidemic campaign’s messages at least nine times in a given month. As the title of this commercial, “Vaping is an Epidemic” suggests, the primary message communicated was that many teens are vaping.

By 2018, government agencies at the federal and state level and several anti-tobacco groups had their own well-funded anti-vaping media efforts underway. The CDC, for example, expanded its $68 million “Tips from Smokers” campaign in 2015 to include warnings that e-cigarettes were not effective for smoking cessation and caused lungs to collapse.48 In the same year, the California Department of Public Health began running television, digital, and outdoor ads in an anti- vaping media blitz projected to cost $75 million over five years.49

Several states, including New York, Colorado, Wisconsin, and Hawaii, along with local health departments throughout the country, began their own anti-vaping marketing plans over the next two years, many with the financial support from the CDC.50 At the same time, anti-tobacco nonprofit groups, like the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids and the Truth Initiative, had already been using social media “influencers,” puppets, creepy mascots, and heavy metal music to explain to teens why they shouldn’t vape, even if their friends do.51

The FDA’s participation in the anti- vaping frenzy assured continued government funding for these efforts. It also guaranteed increasing attention from media, lawmakers, and regulators, which in turn helped expand the reach and clout of the organizations conducting these campaigns, making them more appealing to private donors.

Mo’ Money, Mo’ Problems

The total amount of money allocated by federal, state, and local health departments (or doled out to affiliated health charities) for anti-vaping propaganda is difficult to calculate.

However, spending patterns indicate that, prior to the rising anxiety about youth vaping, the money available for tobacco control projects had been dwindling along with youth smoking rates. Even though adolescent smoking continued to decline, by 2010 those in charge of funding decisions, at both the state and federal level, were suddenly convinced that tobacco control warranted a much bigger slice of state and federal budgets.

Figure 4. High School Smoking/Vaping and Funding for Tobacco Control at FDA/CDC

Author’s calculations using data for FDA Tobacco Control Act funding and CDC funding for the Office on Smoking and Health (National Tobacco Control Program), the American Stop Smoking Intervention Study for Cancer Prevention (ASSIST) program, and Prevention and Control of Tobacco use (IMPACT) program. It does not include time-limited funding, such as Communities Putting Prevention to Work.

Between 2009 and 2014, the funds allocated to the CDC’s Tobacco Control Program (not the only money spent by the agency on the issue) nearly doubled to over $200 million.

Furthermore, in 2009 Congress enacted the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, which created the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products. As of the president’s fiscal year 2020 budget, the Center receives just shy of $800 million for its enforcement, research, and media activities.52

Without a doubt, the escalating panic over youth e-cigarette use fueled these increases in spending on tobacco control. Indeed, the need to address the youth vaping “epidemic” was the reason cited for increasing the FDA’s 2018 budget by $60 million, instituting a new user fee on the e-cigarette industry that would net the Center for Tobacco Products an additional $100 million, and giving the CDC’s budget a $40 million boost.53

Figure 5. Per Capita Expenditure for Tobacco Control in California, 1989-2017

Source: California Department of Public Health, California Tobacco Control Program. California Tobacco Facts and Figures: A Retrospective Look at 2017. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Public Health; 2018, https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CCDPHP/DCDIC/CTCB/CDPH%20Document%20Library/Researchand Evaluation/FactsandFigures/CATobaccoFactsFigures2017_Accessible.pdf.

The same is true at state and local health agencies, where the deluge of youth vaping horror stories facilitated a willingness to spend as much as it takes to fight this emerging health threat.54 In California, for example, the per capita spending on tobacco control programs swelled by 300 percent between 2016 and 2017, spurred in part by the California Department of Public Health’s taxpayer-funded anti-vaping propaganda. In fact, a youth vaping awareness campaign was the sole reason California Governor Gavin Newsom allocated an additional $20 million to CDPH. Thus, this one government department may have spent upwards of $100 million on an anti- vaping messaging targeted at adolescents in the last four years alone.55

What was the result of this spending spree? After two years of suppressed youth vaping, past-month e-cigarette use by high schoolers suddenly spiked in 2018 and climbed even higher in 2019. Those in the tobacco control business blame the e-cigarette industry, but the data tell a different story.

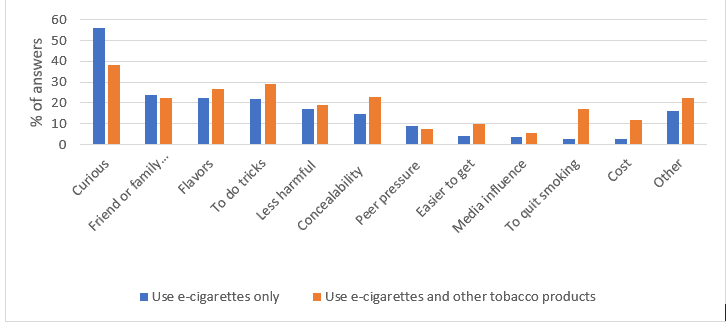

By 2018, the number of flavors on the U.S. market were dwindling and Juul’s once-novel features were no longer new or unique. What was new, however, was the attention given to e-cigarettes by anti-vaping campaigners. Unlike previous years’ surveys, the 2019 edition of the National Youth Tobacco Survey gave students an opportunity to communicate why they chose to vape. Although they could have chosen one or multiple reasons, such as flavors, marketing, peer pressure, easy access, and the ability to hide the devices, the number one answer teens provided for why they vaped, by far, was “curiosity.”56

Figure 6. Reasons for E-Cigarette Use among U.S. Middle and High School Students—National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2019

Assessed by the question, “What are the reasons why you have used electronic cigarettes or e-cigarettes? (Check all that apply.)” Responses were not mutually exclusive.

Andrews McMeel Syndication

This echoes what researchers have found in other countries, like Great Britain, where a majority of adolescents said they used e-cigarettes “just to give them a try.”57 Yet, adolescent vaping in the U.K. has not surged as it has in the U.S. Survey data from 2019 indicate that only 1.7 percent of British minors use e-cigarettes on a weekly basis. Just 6 percent of 11- to 18-year-olds report ever using an e-cigarette in the last month, while in the U.S. about 20 percent of middle and high school students noted any past-month use.58 Those in the U.S. hoping to reduce youth vaping should investigate what caused American, but not British children to become more interested in vaping over the last two years. Is it possible that British young people are just naturally less curious than their American peers? Or does something else explain this disparity in interest? The most likely explanation is not that American youth are taking up vaping in greater numbers despite of multi-million-dollar anti-vaping campaigns, but because of them.

Forbidden Fruit

As a general rule, people don’t like being told what to do. Even mild attempts to sway opinion can be perceived as infringements on personal choice. Such threats to freedom, whether real or imagined, may provoke resistance and an urge to restore one’s sense of autonomy. Most often, this is accomplished by rejecting the attempt to persuade and doing the opposite. The more explicit the attempt and the more dogmatic its tone, the more likely it will be perceived as a threat. And the more important the threatened freedom is to an individual, the more likely he or she is to defend it.59

This phenomenon is what psychologists refer to as “reactance.”60 When done intentionally, it is the principle underlying “reverse psychology.” But, more often than not, reactance is unintentional, generating the opposite effect of what was hoped, a phenomenon known as “backfire.”

The group most prone to experiencing reactance is teenagers. They have a burgeoning desire for independence, but frustratingly little of it. As a result, the value they place on the freedom they do have is heightened, as is the perceived level of threat posed by potential infringements on that freedom. Against this backdrop, attempts to compel, coerce, or manipulate teenagers into adopting certain behaviors or beliefs can provoke a reactant response as they seek to restore their sense of autonomy. Put simply, teenagers rebel and do the opposite of what they are told in order to prove that they can.

It is not easy to avoid triggering reactance, as research shows that people can feel threatened by more than direct commandments, laws, or rules set out by authority figures. Even gentle attempts to persuade, like commercial advertisements, or well- meaning public service announcements, have been shown to cause reactance, unwittingly encouraging the opposite behaviors or beliefs they intended.61

Given young adults’ inclination to reactance, it is not surprising that public health campaigns aimed at them are the most likely to backfire. For example, while anti-smoking messages are effective at discouraging initiation among younger children, the effect disappears as kids age into adolescence, after which explicit messages like this actually seem to increase adolescents’ desire to smoke.62 Drug awareness campaigns, like D.A.R.E., did not discourage adolescent drug use as hoped. Instead, drug use increased among certain groups after their participation in the program.63 Similarly, the national “ My Anti-Drug” campaign, a series of youth-focused ads encouraging abstinence from drugs, were found to be largely unsuccessful. In fact, researchers observed that the more adolescents viewed the ads, the less inclined they were to avoid marijuana use.64 These initiatives failed because, in their effort to convey a particular message, they did not consider what messages people would actually hear.

Causing reactance and rebellion is only one way these campaigns backfire. They can also raise awareness of behaviors or products, make them seem more common than they are or “normal,” or accidentally make these behaviors seem attractive to the target audience. Thus, these advertisements against risky or harmful behaviors unwittingly act as advertisements for them.

Public messaging can draw attention to “problematic” behaviors. If miscalculated, it can convince its intended recipients that these behaviors are socially acceptable. One of the most famous of these was a 1970s anti-littering advertisement featuring a Native American watching in dismay as trash is flung from a passing car, landing on the side of an already litter-strewn highway. The ad was meant to convey the harm that casual littering does to the environment, but actually gave the impression that littering is a widespread practice in modern American society.65 As people are generally motivated to fit in, it is unlikely that the commercial convinced many litterers to stop, and researchers believe it possibly affirmed litterers that the behavior was “normal.”66

Like their inclination to rebel against authority, young people are also more susceptible to the idea of conformity. Thus, campaigns aimed at discourag- ing adolescents from something must take extra care to avoid portraying that behavior as prevalent in their peer group. “Some creative campaigns have sought to exploit this desire to fit in. For example, an effort to reduce binge drinking on a college campus sought to convince students that their peers held negative attitudes about binge drinking and drank less than previously believed. This was communicated through posters, highlighting the results of a campus- wide poll. Clever as the campaign was, it still caused reactance and greater levels of binge drinking because students recognized that the posters were made by an authority figure (the school administration) in an attempt to reduce drinking.67 In other words, they did not trust the information, recognized it as a persuasion attempt, and rejected it as such.

Perhaps the most dangerous error awareness campaigns can make is to accidentally make the behaviors they intend to discourage seem more attractive to the target audience. Often, this sort of messaging backfires by turning a risky or adult product or behavior into something adolescents perceive as a forbidden fruit. Such was the case with content warning labels, meant to deter youth from viewing violent or sexually explicit media. What the architects of such policies did not foresee was that the labels signaling the “adult” nature of the media only increased adolescents’ interest.68 Similarly, warnings about the high-fat content of foods appear to make consumers want to eat them more than they would had there been no warning at all.

Self-Fulfilling Epidemic These psychological principles provide a guideline that public educational campaigns ought to heed. Specifically, if they have any hope of not backfiring they should avoid:

- Making explicit demands on behavior;

- Raising awareness about products or behaviors that did not exist before;

- Making a product/behavior seem more attractive; or

- Portraying the behavior as common or “normal.”

With these rules in mind, it is not difficult to see why anti-vaping campaigns not only failed to discourage youth use but aroused curiosity and encouraged teenagers to experiment with e-cigarettes.

Nearly all of the advertisements created by health departments or med- ical groups centered on the implicit— sometimes explicit—demand that teenagers should not use e-cigarettes, such as the FDA’s “Don’t Get Hacked” spot from 2016. Furthermore, most of these warnings were accompanied by images of adolescents actively vaping. In Don’t Get Hacked, for example, ominous music mimicking the soundtrack of a slasher film plays over images of teenagers vaping. In one instance, a young woman walks into a dark, damp alley to use her e-cigarette. This gives viewers the impression she is doing something risky, which the FDA, no doubt, hoped would make vaping seem less attractive, but the adolescent brain is drawn to novel and risky experiences.70 Showing teenage vapers as if they were characters in a thriller likely only made them and the behavior seem cinematic and cool.

Commercials like these raise awareness of which types of teens vape (almost always physically attractive actors), where they do it, and sometimes even the specific brands they use. In 2018, the California Department of Public Health aired a commercial featuring a boy no older than 13 years old. Shot like a self-made video, the commercial shows the boy reviewing an e-liquid called PBLS Donut, which, after taking a big puff, he calls “good stuff.”71 How many adolescents viewing this ad were previously unaware of this product and how many, once learning of its existence, became curious to try it?

The gravest error almost all of these anti-vaping advertisements make is the repeated insistence that teen vaping is common and socially accepted by teens. In 2016 CDPH began airing an ad featuring “real” California teens discussing vaping. The ad not only features the teenagers vaping on camera, but shows them making statements about how common it is among their friends, how they “tend to be more popular,” do “cool tricks,” and receive sponsorships from vaping companies. One of the “real” teens even declares that if you don’t vape, you are “looked at as an outsider.” Seeing teenagers in the advertisement, adolescent viewers are less likely to see it as a coercive attempt by authorities and more likely to believe its message, but the message it sends is that all the cool kids are vaping and that you won’t fit in if you don’t vape.72

The actual data on youth vaping show that the majority are merely experimenting, with very few vaping habitually. Analysis of the 2018 NYTS data by researchers at the New York University College of Global Public Health found that of the 13.8 percent of students who reported any past month e-cigarette use, half (7 percent) vaped on five or fewer days in the preceding 30-day period. Three quarters (9.9 percent) of those reporting any vaping were current or past tobacco users. Of those who had never smoked or used tobacco, only 2.8 percent reported vaping at all, 0.7 percent reported vaping between six and 19 days, and just 0.4 percent reported vaping on 20 or more days in the past month.73 These numbers hardly warrant the degree of panic we have seen over the last two years.

Yet, since the release of that data, teenagers have kept hearing that youth vaping is an “epidemic.” Had it only been the FDA making this claim, adolescents might not have believed it, but, since the “epidemic” was announced, the news media have parroted the claim in headlines and news segments. This concert of voices, including those not perceived as authority figures, is more responsible than any other factor for increased youth interest in and experimentation with vaping.

Third Party Testimony

Grifters have long known about the power of third-party persuasion. For example, having an accomplice in a crowd and showing him or her winning a shell game is a well-known method of overcoming skepticism and convincing the rest of the crowd to lose their money to the grift.

Advertising professionals employ a similar trick with third-party marketing or earned media.

A press release from a company about its rosy financial outlook is unlikely to attract many investors. But if that release is repackaged into a news story and published by a news outlet, it may succeed in improving the public perceptions of that company.

Similarly, a production company hoping to drum up interest in a new film would not get far by simply telling audiences how great a movie is, but a few dozen positive

independent reviews may convince a large number of people to head to their local movie theater to see it.

Whether part of a marketing strategy or not, the media’s repetition that there was a youth vaping “epidemic” made the American public, including adolescents, far more likely to believe this was the case than if it had only been the FDA or other authority figures making such statements. This persuaded big money investors, like former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, to commit hundreds of millions of dollars to the cause.74 But the message that youth vaping is an “epidemic” also provided compelling evidence to adolescents that all of their friends were vaping, even if they weren’t seeing it.

This is not the outcome those trying to reduce youth interest vaping wanted, but that is exactly what they got, as the results of a national survey released in December found. Like the CDC’s National Youth Tobacco

Survey, the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan’s Monitoring the Future (MTF) study provides an overview of drug use among eighth, 10th and 12th grade students in the U.S. Like the NYTS, the 2019 MTF survey found increases in youth vaping. But, unlike NYTS, MTF actually differentiates between what adolescents vape.75 Like NYTS, the MTF survey found increases in the number of high school students who reported vaping nicotine e-cigarettes. It also found that the number of adolescents who said they vaped marijuana has more than doubled in the last year.76

Most interestingly, while the MTF found no increase in lifetime, past-year, or past-month marijuana use among high school students, it found a massive rise in teens vaping marijuana. The number of students who reported vaping THC (psycho-active ingredient in cannabis) doubled in a single year. Thus, while marijuana use has become more socially acceptable and increasingly legal throughout the U.S. it does not appear that teen interest in marijuana has changed over the last year. Their interest in vaping, however, has increased substantially.

Unlike the nicotine/e-cigarette issue, this rise in youth THC vaping cannot be blamed on Juul. It cannot be blamed on high nicotine content, predatory marketing, or “kid friendly” flavors. Indeed, the only thing that explains increases in both teen vaping of nicotine and THC vaping is the upsurge in anti-vaping messaging that occurred over this same period.

Conclusion

It is reasonable for anti-tobacco advocates to worry about youth experimentation with nicotine, but the evidence is clear that their interventions have backfired and made the problem worse. Their attempts to dissuade teenagers from vaping increased their awareness of the behavior, made it more attractive, and convinced them that everyone around them was doing it.

Anti-tobacco advocates argue that the government can end the “epidemic” by raising the minimum tobacco age to 21, banning non-tobacco e-cigarette flavors, and increasing funding for anti-vaping education. But, as this paper has demonstrated, these measures will not only fail, they will actually make matters worse by increasing the coolness of vaping and youth attraction to it.

Teen vaping did not escalate despite the increased anti-vaping messaging. Adolescents’ curiosity and subsequent experimentation with vaping rose because of anti-vaping messaging.

Heeding tobacco control advocates’ advice and giving them more money to spread their propaganda is the last thing policy makers should do.

NOTES

- U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Oversight and Reform, Oversight Subcommittee Hearing Examined Outbreak of E-Cigarette-Related Lung Disease, September 25, 2019,

https://oversight.house.gov/news/press-releases/oversight-subcommittee-hearing-examined-outbreak-of-e-cigarette-related-lung.

- Lion Shahab, Maciej L Goniewicz, Benjamin C Blount, Jamie Brown, Ann McNeill, K. Udeni Alwis, June Feng, Lanqing Wang, and Robert West, “Nicotine, Carcinogen, and Toxin Exposure in Long-Term E-Cigarette and Nicotine Replacement Therapy Users: A Cross-sectional Study,” Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 166, No. 6 (March 2017), pp. 390-400, https://annals.org/aim/article-abstract/2599869/nicotine-carcinogen-toxin-exposure-long-term-e-cigarette-nicotine-replacement. Peter Hajek, Anna Phillips-Waller, Dunja Przulkj, Francesca Pesola, Katie Myers Smith, Natalie Bisal, Jinshuo Li, Steve Parrott, Peter Sasieni, Lynne Dawkins, Louise Ross, Maciej Goniewicz, Qi Wu, and Hayden J. McRobbie, “A Randomized Trial of E-Cigarettes versus Nicotine-Replacement Therapy,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 380, No. 7 (February 2019), pp. 629-637, https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1808779.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Lesson 1: Introduction to Epidemiology, Section 11: Epidemic Disease Occurrence,” in Principles of Epidemiology in Public Health Practice, Third Edition, An Introduction to Applied Epidemiology and Biostatistics,” originally published October 2006, updated November 2011, https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dsepd/ss1978/lesson1/section11.html.

- Robert West, Jamie Brown, and Martin Jarvis, “Epidemic of youth nicotine addiction? What does the National Youth Tobacco Survey reveal about high school e-cigarette use in the USA? (Preprint),” Qeios, October 7, 2019, https://www.qeios.com/read/article/391.

- Brian A. King, Roshni Patel, Kimberly H. Nguyen, and Shanta R. Dube, “Trends in Awareness and Use of Electronic Cigarettes among US Adults, 2010–2013,” Nicotine and Tobacco Research, Vol. 17, Issue 2 (February 2015), pp. 219-227, https://academic.oup.com/ntr/article/17/2/219/2858030.

- Andrea S. Gentzke, MeLisa Creamer, Karen A. Cullen, Bridget K. Ambrose, Gordon Willis, Ahmed Jamal, and Brian A. King, “Vital Signs: Tobacco Product Use among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2011–2018,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 68, Issue 6 (February 11, 2019), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, pp. 157-164, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6806e1.htm.

- René A. Arrazola, Linda J. Neff, Sara M. Kennedy, Enver Holder-Hayes, and Christopher D. Jones, “Tobacco Use among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2013,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 63, Issue 45 (November 2014), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, pp. 1021-1026, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6345a2.htm. Tushar Singh, René A. Arrazola, Catherine G. Corey, Corinne G. Husten, Linda J. Neff, David M. Homa, and Brian A. King, “Tobacco Use among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2011–2015,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 65, Issue 14 (April 2016), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, pp. 361-367, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6514a1.htm.

- Teresa W. Wang, Andrea Gentzke, Saida Sharapova, Karen A. Cullen, Bridget K. Ambrose, and Ahmed Jamal, “Tobacco Product Use among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2011–2017,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 67, Issue 22 (June 2018), pp. 629-633, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm6722a3.htm.

- Grace Kong and Suchitra Krishnan-Sarin, “A call to end the epidemic of adolescent E-cigarette use,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Vol. 174 (May 2017), pp. 215-221, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0376871617301023?via%3Dihub.

- Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, “CDC Survey Finds Youth E-Cigarette Use More than Doubled from 2011-2012, Shows Urgent Need for FDA Regulation,” news release, September 5, 2013,

https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/press-releases/2013_09_05_ecigarettes. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “E-Cigarette Use among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General,” 2016,

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK294302. American Academy of Family Physicians, “AAFP, others applaud surgeon general’s report on e-cigarettes,” news release, December 12, 2016,

https://www.aafp.org/news/health-of-the-public/20161212sgreporte-cigs.html.

- “Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on new enforcement actions and a Youth Tobacco Prevention Plan to stop youth use of, and access to, JUUL and other e-cigarettes,” U.S. Food and Drug Administration, April 23, 2018, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/statement-fda-commissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-new-enforcement- actions-and-youth-tobacco-prevention.

- Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, “Broken Promises to Our Children: A State-by-State Look at the 1998 Tobacco Settlement 20 Years Later,” December 14, 2018, https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/content/what_we_do/state_local_issues/settlement/FY2019/2018_State_Report.pdf.

- Declan Harty, “Juul Hopes to Reinvent E-Cigarette Ads with ‘Vaporized’ Campaign,” Ad Age, June 23, 2015,

https://adage.com/article/cmo-strategy/juul-hopes-reinvent-e-cigarette-ads-campaign/299142.

- Jared Wadley, “Vaping, hookah use by US teens declines for first time,” University of Michigan News, December 13, 2016, https://news.umich.edu/vaping-hookah-use-by-us-teens-declines-for-first-time.

- Ivan Couronne, “JUUL: e-cigarette dominates the market—and fears of parents,” Medical Xpress, October 3, 2018,

https://medicalxpress.com/news/2018-10-juul-e-cigarette-dominates-marketand-parents.html.

- Natalie Sherman, “Juul: The rise of a $38bn e-cigarette phenomenon,” BBC News, January 6, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-46654063.

- Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, “Broken Promises to Our Children.”

- Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, “Leading Health Groups Urge FDA to Stop Sales of New, Juul-Like E-Cigarettes Illegally Introduced Without Agency Review,” news release, August 07, 2018,

https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/press-releases/2018_08_07_new_ecig_products. “Best Pod Vapes & JUUL Alternatives,”

Vaping360, updated December 4, 2019, https://vaping360.com/best-vape-mods/pod-vapes.

- Laura Bach, “JUUL and Youth: Rising E-Cigarette Popularity,” Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, January 9, 2018, https://bit.ly/2HgH0er.

- Electric Tobacconist, retail website, accessed February 5, 2020,

https://www.electrictobacconist.com/nicotine-salt-c78/50mg-a174.

- Jessica M. Yingst, Shari Hrabvsky, Andrea Hobkirk, Neil Trushin, John P. Richie Jr., and Jonathan Foulds, “Nicotine Absorption Profile among Regular Users of a Pod-Based Electronic Nicotine Delivery System,” JAMA Open Network, Vol. 2 Issue 11 (November 2019), pp. e1915494- e1915498, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2755483.

- Erin Johnson, “The Rising Wave of Salt Nicotine E-juice,” Smoke & Vape Business Solutions, January 19, 2018,

https://smokeandvapemagazine.com/editorial/the-rising-wave-of-salt-nicotine-e-juice. Ejouce. Deals, retail website, accessed February 5, 2020, https://ejuice.deals/collections/nicotine-salt-ejuice.

- “Best Nicotine Salt E-Juices 2019,” Electronic Tobacconist, August 7, 2019,

https://www.electrictobacconist.com/blog/2019/08/best-nicotine-salt-e-juices-2019/.

- Emily Baumgaertner, “Fruity flavors lure teens into vaping longer and taking more puffs, study says,” Los Angeles Times, October 27, 2019, https://www.latimes.com/science/story/2019-10-27/fruity-flavors-lure-teens-into-vaping-longer.

- Kyle O’Brien, “California points out flavor deception for kids in the tobacco industry’s new products,” The Drum, April 30, 2018,

- Zare, Samane, Mehdi Nemati, and Yuqing Zheng, “A systematic review of consumer preference for e-cigarette attributes: Flavor, nicotine strength, and type,” PLOS One, March 15, 2018, http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0194145.

- Konstantinos E Farsalinos, Giorgio Romagna, Dimitris Tsiapras, Stamatis Kyrzopoulos, Alketa Spyrou, and Vassilis Voudris,

“Impact of Flavour Variability on Electronic Cigarette Use Experience: An Internet Survey,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Vol. 10 Issue 12 (December 2013), pp: 7272 – 7282, https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/10/12/7272.

- Caitlin Notley, Emma Ward, Lynne Dawkins, and Richard Holland, “The unique contribution of e-cigarettes for tobacco harm

reduction in supporting smoking relapse prevention,” Harm Reduction Journal, Vol. 15, Article 31 (2018), https://harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12954-018-0237-7.

- Saul Shiffman, Mark A. Sembower, Janine L. Pilliteri, Karen K. Gerlach, and Joseph G. Gitchell, “The Impact of Flavor

Descriptors on Nonsmoking Teens’ and Adult Smokers’ Interest in Electronic Cigarettes,” Nicotine & Tobacco Research, Vol. 17, Issue 10 (October 2015), pp. 1255-1262, https://academic.oup.com/ntr/article-abstract/17/10/1255/1028251.

- Foundation for Advancing Alcohol Responsibility, “The Fight Against Underage Drinking—Stats on Teen Alcohol Use,”

accessed December 30, 2019, https://www.responsibility.org/alcohol-statistics/underage-drinking-statistics.

- Christopher Russell, Neil McKeganey, Tiffany Dickson, and Mitchell Nides, “Changing patterns of first e-cigarette flavor used and current flavors used by 20,836 adult frequent e-cigarette users in the USA,” Harm Reduction Journal, Vol. 15, Issue 5 (June 2018), pp. 33-14, https://harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12954-018-0238-6. Bloomberg Philanthropies, “Bloomberg Philanthropies Launches New $160 Million Program to End the Youth E-Cigarette Epidemic,” news release, September 10, 2019,

https://www.bloomberg.org/press/releases/bloomberg-philanthropies-launches-new-160-million-program-end-youth- e-cigarette-epidemic/.

- Truth Initiative, “JUUL Fails to remove all of youth’s favorite flavors from stores,” November 15, 2018, https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/emerging-tobacco-products/juul-fails-remove-all-youths-favorite-flavors-stores.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Youth and Tobacco Use,” December 20, 2019, https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/youth_data/tobacco_use/index.htm.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General,” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK99237/.

- M. Jane Lewis and Olivia Wackowski, “Dealing with an Innovative Industry: A Look at Flavored Cigarettes Promoted by Mainstream Brands,” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 96, Issue 2 (February 2006), pp. 244-251, https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2004.061200. Sarah M. Klein, Gary A. Giovino, Dianne C. Barker, Cindy Tworek, K. Michael Cummings, and Richard J. O’Connor, “Use of flavored cigarettes among older adolescent and adult smokers: United States, 2004 –2005,” Nicotine & Tobacco Research, Vol. 10 No. 7 (July 2008), pp. 1209-1214, http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.844.7714&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

- Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich, “R.J. Reynolds Agrees to Stop Selling Flavored Cigarettes,” news release, October 11, 2006, https://www.azag.gov/press-release/r-j-reynolds-agrees-stop-selling-flavored-cigarettes.

- Emily Price, “E-Cigarette Company Juul Will Stop Selling Most of Its Flavored Pods in Stores,” Fortune, November 13, 2018, https://fortune.com/2018/11/13/juul-flavored-pod-ban.

- Teresa W Wang, Andrea S Gentzke, MeLisa R Creamer, Karen A. Cullen, Enver Holder-Hayes, Michael D. Sawdey,

Gabriella M. Anic, David B. Portnoy, Sean Hu, David M. Homa, Ahmed Jamal, and Linda J. Neff, “Tobacco Product Use and Associated Factors among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2019,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly

Report, Vol. 68, Issue 12 (December 6, 2019), pp. 1-22, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/ss/ss6812a1.htm.

- Laura Bach, “Where do youth get their e-cigarettes,” Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, December 3, 2019, https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/factsheets/0403.pdf.

- Truth Initiative, “JUUL Fails to remove all of youth’s favorite flavors from stores.”

- Christine Fisher, “The FTC is reportedly investigating Juul’s teen marketing tactics,” Endgadget, August 29, 2019, https://www.engadget.com/2019/08/29/juul-ftc-investigates-marketing-teen-vaping.

- Melanie Wakefield, Yvonne Terry-McElrath, Sherry Emery, Henry Saffer, Frank J. Chaloupka, Glen Szczypka, Brian Flay, Patrick M. O’Malley, and Lloyd D. Johnston, “Effect of Televised, Tobacco Company-Funded Smoking Prevention Advertising on Youth Smoking-Related Beliefs, Intentions, and Behavior,” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 96 Issue 12 (December 2006), pp. 2154-2160, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1698148/?tool=pmcentrez&report=abstract.

- Laurie McGinley, “FDA chief calls youth e-cigarettes an ‘epidemic,’” Washington Post, September 12, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/fda-chief-calls-youth-use-of-juul-other-e-cigarettes-an-epidemic/ 2018/09/12/ddaa6612-b5c8-11e8-a7b5-adaaa5b2a57f_story.html.

- Brad Rody, “The 2018 American Teen Vaping Epidemic, Recalculated,” Tobacco Truth, https://rodutobaccotruth.blogspot.com/2019/05/the-2018-american-teen-vaping-epidemic.html.

- Kathleen Crosby, Mark Greenwold, Carrie Wade, “Protecting Youth: Targeting Appropriate E-Cigarette Users,” PowerPoint Presentation (panel moderated by J. Benneville Haas, Food and Drug Law Institute, October 25, 2018, https://www.fdli.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/345-Protecting-Youth-1.pdf?fbclid=IwAR0-QyS2u-Zp7y4e-3jMo_ AzsOX8q22KxOFV_hnSOkr9_plPtkhyFonqI4o.

- The Real Cost TV Commercial, “Hacked,” 2016, https://www.ispot.tv/ad/AFV3/the-real-cost-hacked.

- Patrick Coffee, “The FDA’s Anti-Tobacco Wing Extends Its $625 Million Relationship with FCB for Another 5 Years,”

AdWeek, April 19, 2017,

https://www.adweek.com/agencyspy/the-fdas-anti-tobacco-wing-extends-its-625-million-relationship-with-fcb-for-another-5- years/129841.

- John Tozzi, “The CDC’s Anti-Smoking Ads Now Include E-Cigarettes,” Bloomberg Business, March 26, 2015, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-03-26/the-cdc-s-anti-smoking-ads-now-include-e-cigarettes.

California Tobacco Control Program RFP MEDIA 14-10003 Advertising Campaign, https://tcfor.catcp.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=opportunities.viewArchivedOpp&oppID=41. Duncan/Channon, “California debuts ads to counter e-cigs,” news release, March 23, 2015,

California Tobacco Control Program RFP MEDIA 14-10003 Advertising Campaign, https://tcfor.catcp.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=opportunities.viewArchivedOpp&oppID=41. Duncan/Channon, “California debuts ads to counter e-cigs,” news release, March 23, 2015,

https://www.duncanchannon.com/2015/03/and-we-quote-california-debuts-ads-to-counter-e-cigarettes/. Julia Olennikova, “SEMrush Study: Most Expensive States to Advertise In (+ Breakdown by 17 Industries),” news release, SEMrush, February 19, 2018, updated September 4, 2018, https://www.semrush.com/blog/semrush-study-most-expensive-states-to-advertise-in/.

- Tony Ottomanelli II, “NY State Launches an Anti-Vape Campaign Rip-off of Still Blowing Smoke,” VapingPost, May 26, 2017, https://www.vapingpost.com/2017/05/26/ny-state-anti-vape-campaign/. Tobacco Free CO, “Vaping 101: What You Need to Know,” accessed February 5, 2020, https://www.tobaccofreeco.org/know-the-facts/vaping-101/. Ken Krall, “State Launches Anti-Tobacco Campaign After Youth Use Rises,” WXPR, November 7, 2017,

www.wxpr.org/post/state-launches-anti-tobacco-campaign-after-youth-use-rises#stream/0. Hawai’i Public Health Institute, 808NOVAPE campaign, accessed February 5, 2020,

https://www.hiphi.org/808novape-campaign-breathes-aloha-onto-the-walls-of-schools-across-the-state/. Carley Thompson, Meet the 5 Chemicals You Didn’t Know Were in Vaping Products,” Public Health Insider: Official Insights from Public Health—Seattle & King County Staff,” June 14, 2017,

https://kingcountyschoolhealth.com/2017/06/28/escape-the-vape-campaign/. Danielle Venton, “The War Over Vaping’s Health Risks Is Getting Dirty,” Wired, April 2, 2015, https://www.wired.com/2015/04/war-vapings-health-risks-getting-dirty. City of Chicago, Office of the Mayor, “Mayor Emanuel and the Department Of Public Health Announce Campaign to Reduce and Prevent Youth Vaping,” news release, December 23, 2015, https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/depts/mayor/press_room/press_releases/2015/december/mayor-emanuel-and-the-department- of-public-health-announce-campa.html. Matt Rowland, “Pasadena, CA: CDC-funded anti-tobacco campaign calls vapers ‘stupid sheep,’” Vapes, November 22, 2016,

- Daphne Chen, “Joining lawmakers, students rally against e-cigarettes,” Deseret News, February 17, 2016, https://www.deseret.com/2016/2/17/20582803/joining-lawmakers-students-rally-against-e-cigarettes#representatives-of-the- anti-tobacco-youth-coalition-outrage-attend-an-event-at-the-capitol-in-salt-lake-city-on-wednesday-feb-17-2016-the-group- was-at-the-capitol-to-discuss-their-concerns-about-the-ease-of-youth-access-to-tobacco-and-e-cigarette-products-and-their- desire-to-change-the-legal-age-to-purchase-them-from-19-to-21.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Justification Estimates for Appropriations Committees, Fiscal Year 2020, https://www.fda.gov/media/121408/download.

- Tom Lisi and Paul Swiech, “More kids are vaping. The FDA is spending $60 million to change that,” Herald & Review, September 22, 2018,

https://herald-review.com/lifestyles/health-med-fit/more-kids-are-vaping-the-fda-is-spending-million-to/article_c069f7b2- 293a-5aa9-b120-c7da19d61d52.html. Laurie McGinley, “Trump wants the e-cigarette industry to pay $100 million a year in user fees, Washington Post, March 11, 2019,

https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2019/03/11/trump-wants-e-cigarette-industry-pay-million-year-user-fees. Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies Appropriations Bill, 2020, Report of the Committee on Appropriations, House of Representatives, on H.R. 2740, together with Minority Views, May 15, 2019, https://www.congress.gov/116/crpt/hrpt62/CRPT-116hrpt62.pdf.

- California Department of Public Health, CA Tobacco Control Program, “California Tobacco Facts & Figures 2018,” https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CCDPHP/DCDIC/CTCB/CDPH%20Document%20Library/ResearchandEvaluation/ FactsandFigures/CATobaccoFactsFigures2017_Accessible.pdf.

- Associated Press, “Gov. Newsom Announces Plan to Spend $20 Million on Vaping Awareness Campaign, Crackdown on Illegal Sales,” KTLA6, September 16, 2019,

https://ktla.com/2019/09/16/gov-newsom-announces-plan-to-spend-20-million-on-vaping-awareness-campaign-crackdown- on-illegal-sales.

- Teresa W Wang, Andrea S Gentzke, MeLisa R Creamer, et al, “Tobacco Product Use and Associated Factors among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2019,” https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/ss/ss6812a1.htm#T6_down.

- Action on Smoking and Health, “Use of e-cigarettes among young people in Great Britain,” fact sheet, June 2019, https://ash.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/ASH-Factsheet-Youth-E-cigarette-Use-2019.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Brad J. Bushman and Angela D. Stack, “Forbidden fruit versus tainted fruit: Effects of warnings labels on attraction to television violence,” Journal of Experimental Applied Psychology, Vol. 2, Issue 3 (September 1996), pp. 207-226, https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1996-06304-002.

- Christina Steindl, Eva Jonas, Sandra Sittenthaler, Eva Traut-Mattausch, and Jeff Greenberg, “Understanding Psychological Reactance: New Developments and Findings,” Zeitschrift für Psychologie (December 8, 2015), pp. 205-214, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4675534/.

- Marieke L Fransen, Edith G. Smit, and Peeter W.J. Verlegh, “Strategies and motives for resistance to persuasion: an integrative framework,” Frontiers in Psychology, 2015, Vol. 6 (August 2015), pp. 6-18, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01201/full.

- Joseph Grandpre, Eusebio M. Alvaro, Michael Burgoon, Claude H. Miller, and John R. Hall, “Adolescent Reactance and Anti-Smoking campaigns: A Theoretical Approach,” Health Communication, Vol. 15, Issue 3 (2003), pp. 349-366, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1207/S15327027HC1503_6.

- Dennis P. Rosenbaum and Gordon S. Hanson, “Assessing the Effects of School-Based Drug Education: A Six-Year Multilevel Analysis of Project D.A.R.E.,” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, Vol. 35, Issue 4 (November 1998), pp. 381-412, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0022427898035004002.

- Robert Hornik, Lela Jacobsohn, Robert Orwin, Andrea Piesse, and Graham Kalton, “Effects of the National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign on Youths,” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 98, Issue 12 (December 2008), pp. 2229-2236, https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2007.125849.

- Robert B. Cialdini, “Crafting Normative Messages to Protect the Environment,” Current Directions in Psychological Science, Vol. 12, No. 4 (August 2003), pp. 105-109, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1111/1467-8721.01242.

- Robert B. Cialdini, “Crafting normative messages to protect the environment,” Current Directions in Psychological Science, Vol. 12, Issue 4 (August 2003), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1467-8721.01242.

- Taejin Jung, Woomi Shim, and Thad Mantaro, “Psychological Reactance and Effects of Social Norms Messages among Binge Drinking College Students,” Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, Vol. 54, Issue 3 (December 2010), pp. 7-18.

- Bushman and Stack, “Forbidden fruit versus tainted fruit.”

- Brad J. Bushman, “Effects of warning and information labels on consumption of full-fat, reduced fat, and no-fat products,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 83, No. 1 (1998), pp. 97-101, https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0021-9010.83.1.97.

- Daniel Romer, Valerie F. Reyna, and Theodore D. Satterthwaite, “Beyond Stereotypes of Adolescent Risk Taking: Placing the Adolescent Brain in Developmental Context,” Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, October 2017, https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/518/.

- TobaccoFreeCA, “15,500 flavors exist for use in e-cigarettes,” Facebook video, September 16, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/TobaccoFreeCA/videos/1812251025530747/.

- TobaccoFreeCA, “Real California teens talk about vaping,” YouTube video, October 25, 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=gjYT4YG7jOk. One interview talks about some of her friends being sponsored at 1:45.

- Allison M Glasser, Amanda L Johnson, Raymond S Niaura, David B Abrams, and Jennifer L Pearson, “Youth Vaping and Tobacco Use in Context in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Youth Tobacco Survey,” Nicotine & Tobacco Research, January 13, 2020,

https://academic.oup.com/ntr/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/ntr/ntaa010/5701081?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

- Cancer Action Network, “Bloomberg Philanthropies Launches New $160 Million Program to End the Youth E-Cigarette Epidemic,” news release, September 10, 2019,

https://www.fightcancer.org/releases/bloomberg-philanthropies-launches-new-160-million-program-end-youth-e-cigarette- epidemic.

- Although the NYTS previously collected data on the number of youths who also vaped marijuana in 2016, 2017, and 2018, it removed the question in 2019. Michael B. Siegel, “CDC is Concealing and Suppressing Information on Youth Marijuana Vaping to Over-hype Harms of E-Cigarettes” The Rest of the Story, January 26, 2020, https://tobaccoanalysis.blogspot.com/2020/01/cdc-is-concealing-and-suppressing.html?fbclid=IwAR3iOUBYYE01Zi0 oAbUCWVYFLB72YWK204qCp0Z1xGiXUNyyhPgMBcS1jAM.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse, “Vaping of marijuana on the rise among teens,” news release, EurekaAlert, American Association for the Advancement of Science, December 18, 2019,

https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2019-12/niod-vom121719.php.