The Rules for Rulemaking: a Cheat-Sheet Glossary of the Administrative State

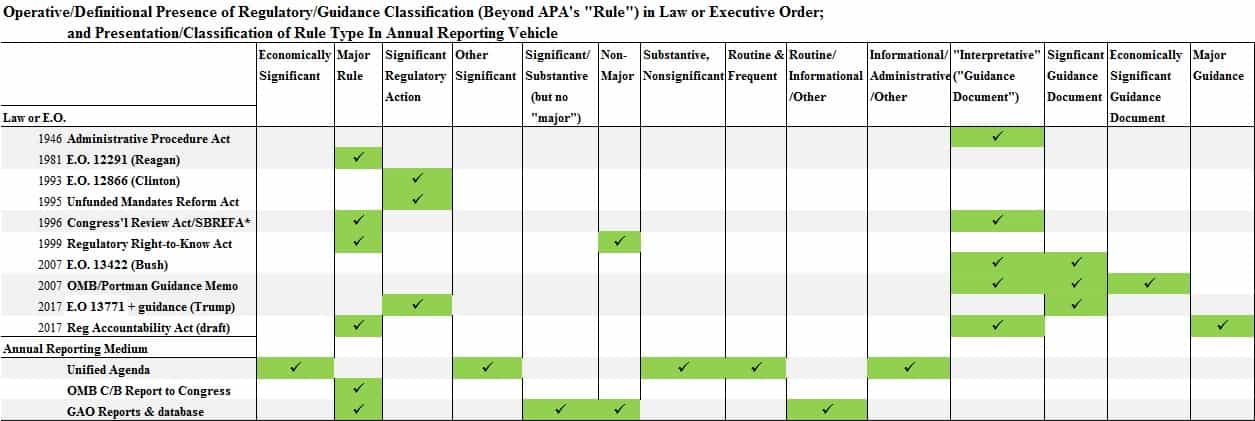

The following chronological overview of America’s regulatory oversight regime emerged from noticing the many categories of rules and regulations in play in the insiders’ game of administrative law and regulatory practice. Jargon and nomenclature are substantial, maybe even numbing. Since some rules and guidance documents can slide by unmeasured and unaccounted for, bipartisan streamlining would be wise.

Administrative Procedure Act (1946) — Offspring: “rule,” “interpretative rule”

The basis of the modern federal regulatory apparatus is the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) of 1946 (P.L. 79-404). In the years after the New Deal, the APA established the notice-and-comment rulemaking process (Section 553 rulemaking) consisting of formal advance notification of rulemakings with an opportunity for the public to provide feedback on a published proposed rule before it is finalized in the Federal Register.

However, the APA’s rulemaking process allows for a great deal of wiggle room via its “good cause” exemption, by which an agency may deem notice and comment for certain rules as “impracticable, unnecessary, or contrary to the public interest.” Further, agency “interpretative rules” (often called guidance documents or interpretive rules) and “general statements of policy” are not subject to notice and comment. These are sometimes controversial.

Interestingly the word “regulation” does not appear in the APA.

Regulatory Flexibility Act (1980)

The Regulatory Flexibility Act (RFA), signed by President Jimmy Carter in 1980, directed federal agencies to prepare regulatory flexibility analyses to assess certain of their rules’ effects on small businesses and to describe regulatory actions under development “that may have a significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities.” The Act did not name types of rules, but is noteworthy for a couple reasons. First, it ushered in the terms “significant” and “economic,” which have become central in modern regulatory review. Second, the RFA created the twice-yearly “Regulatory Agenda,” a reporting instrument shortly afterward supplemented by President Ronald Reagan’s Executive Order 12291, which itself contributed to the expansion of regulatory taxonomy.

Executive Order 12291 (1981) — Offspring: “regulation,” “major rule,” reaffirms “rule”

A more activist central regulatory assessment and review process was formalized by President Reagan and implemented by the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) within the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). OIRA had been created earlier by the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1980, which had been signed into law by President Jimmy Carter. OIRA’s founding charge was reducing governmental and private sector paperwork burdens. President Reagan expanded OIRA’s authority in 1981 with Executive Order 12291 on “Federal Regulation.” The order directed that OIRA, acting as central reviewer, evaluate agencies’ rules and analyses, that any new “major” executive agency regulation’s benefits outweigh costs where not prohibited by statute, and that agencies prepare a regulatory impact analysis (which could be combined with the already required regulatory flexibility analysis) “in connection with every major rule.” Independent agencies, while subject to APA’s notice-and-comment, were not subjected (thought they might have been and still may be) to enforceable regulatory review under the executive order (E.O. 12291, for example, states: “‘Agency’ means any authority of the United States that is an ‘agency’ under 44 U.S.C. 3502(1), excluding those agencies specified in 44 U.S.C. 3502(10)”).

Executive Order 12866 (1993) — Offspring: “regulatory action,” “significant regulatory action,” and (indirectly) “economically significant,” reaffirmed “regulation” and “rule”

On September 30, 1993, President Bill Clinton replaced Reagan’s Executive Order 12291 with Executive Order 12866 “Regulatory Planning and Review,” which largely still governs today. The order retained the central regulatory review structure but weakened central review by “reaffirm[ing] the primacy of Federal agencies in the regulatory decision-making process.” The Reagan criterion that benefits “outweigh” costs (Sec. 2(b): “Regulatory action shall not be undertaken unless the potential benefits to society for the regulation outweigh the potential costs to society”) became a weaker stipulation that benefits “justify” costs (Sec. 1(b)(6): “Each agency shall assess both the costs and the benefits of the intended regulation and, recognizing that some costs and benefits are difficult to quantify, propose or adopt a regulation only upon a reasoned determination that the benefits of the intended regulation justify its costs”). The order retained requirements for executive branch—not independent—agencies to assess costs and benefits of “significant” proposed and final regulatory actions, conduct cost-benefit analysis of what are now referred to as “economically significant” rules ($100 million or more in economic impact), and assess “reasonably feasible alternatives” that OIRA would review. (Interestingly, like the way the APA never defined “regulation”, there is actually not a law, statute nor executive order that defines “economically significant.”)

Reagan’s regulatory Agenda became supplemented by the Regulatory Plan presenting “the most important significant regulatory actions that the agency reasonably expects to issue in proposed or final form in that fiscal year or thereafter.” (The appearance of this document is the occasion during which the Trump administration has updated the public on its one-in, two-out program for regulation.) E.O. 12866 also declared that for purposes of preparing the Regulatory Agenda, “the term “agency” or “agencies” “shall also include those considered to be independent regulatory agencies.” Independent agencies remained and still remain exempt from preparing regulatory impact analysis for significant regulatory actions.

Unfunded Mandates Reform Act (1995) — Offspring: a statutory characterization of “regulation,” reaffirms “rule” and “significant regulatory action”

While it did not introduce new terms, another reform affecting today’s regulatory oversight process was the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act (UMRA) of 1995 (P.L. 104-4). Dubbed “S. 1” in the Senate, the legislation was driven largely by complaints from local and state government officials about Washington rules and mandates disrupting their jurisdictions’ budgetary priorities. The bill required the Congressional Budget Office to produce cost estimates of a regulation or rule (using the APA’s meaning) imposing mandates that affect state, local, and tribal governments that it determines to rise above a then-$50 million threshold (now $77 million) and the private sector over $100 million.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) has noted numerous exceptions to the requirement to conduct analysis under UMRA over the years, which has undermined its usefulness. For example, while the $100 million threshold for preparing detailed “written statements” appears, the requirement holds only “before promulgating any final rule for which a general notice of proposed rulemaking was published.” Proposed rulemakings often are sometimes not published in the first place, so the statements are often not triggered. Also, as the Congressional Research Service has noted, the $100 million applies to “expenditures” imposed on lower-level governments or the private sector, which are different from the less direct economic effects that help determine rule significance.

Congressional Review Act (1996) — Offspring: a statutory definition of “major rule,” reaffirms “rule”

The 1996 Congressional Review Act (CRA) requires agencies to submit to both houses of Congress and to the Comptroller General of the Government Accountability Office “a copy of the rule” (this includes guidance as well, though often ignored) and a descriptive statement including whether or not it is “major.” The CRA was passed with significant bipartisan support as Section 251 of the Contract with America Advancement Act, which also contained the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act, which itself updated the Regulatory Flexibility Act.

Under CRA, the GAO submits reports to Congress on major rules—those with at least $100 million in estimated annual costs—that are maintained in a GAO database. The CRA gives Congress 60 legislative days to review a final major rule and pass a resolution of disapproval, which gets expedited treatment in the Senate. The CRA is one of the more important recent affirmations of congressional authority over regulation, but until the Trump administration’s rejection of 15 rules and one guidance document so far, only one rulehad been rolled back—a Labor Department ergonomics rule in early 2001. Agencies often fail to submit final rules properly to the GAO and Congress, as required under the law.

Regulatory Right-to-Know Act (2000) — Offspring: “non-major rule,” reaffirms “major rule”

Passed as part of the Treasury Department appropriations bill in 2000, the Regulatory Right-to-Know Act formalized in statute the requirement that the OMB prepare an annual report to Congress“containing an estimate of the total annual costs and benefits of Federal regulatory programs, including rules and paperwork”:

- In the aggregate;

- By agency, agency program, and program component, and;

- By major rule.

This annual submission, the primary federal government document outlining some costs and benefits of major rules to the public, is called Report to Congress on the Benefits and Costs of Federal Regulations and Agency Compliance with the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act and archived online.

Executive Order 13422 and OMB Director Portman Bulletin on Guidance (2007) — Offspring: “guidance document,” “significant guidance document,” “economically significant guidance document”

President George W. Bush’s Executive Order 13422, amending Clinton’s 12866, required identifying “the specific market failure” that regulations were presumed to address rather than general ones. The order also subjected significant guidance to heightened OMB review by stipulating that agencies provide OIRA “with advance notification of any significant guidance documents.”

Rob Portman, Director of the OMB at the time, and now a Republican Senator from Ohio, issued shortly thereafter the 2007 Final Bulletin for Agency Good Guidance Practices—in effect, guidance for guidance. With respect to “significant guidance documents,” and “economically significant guidance documents,” some executive, though not (typically) independent, agencies comply or make nods toward compliance with the Good Guidance Principles (GGP), including publishing some of their guidance online. But like non-major rules or those not deemed significant, there is a great deal of lesser guidance, or potentially undeclared significant guidance, issued by agencies that remains unreviewed.

Obama Executive Orders on Regulation

President Obama’s Executive Order 13497 revoked Bush’s E.O. 13422 on guidance early in his presidency, but in March 2009, then-OMB Director Peter Orszag issued a memorandum to “clarify” that “documents remain subject to OIRA’s review under [longstanding Clinton] Executive Order 12866.”

In 2011, President Obama issued three executive orders regarding regulation:

- Executive Order 13565, on Improving Regulation and Regulatory Review, which reaffirmed Clinton’s Executive Order 12866 and expressed a pledge to address unwarranted federal regulation (Federal Register, Vol. 76, No. 14, January 21, 2011). The president achieved a few billion dollars in savings, even wisecracking in the 2013 State of the Union Address about a rule that had categorized spilled milk as an “oil”.

- Executive Order 13579, Regulation and Independent Regulatory Agencies, called on—though did not mandate—independent agencies to improve disclosure. As noted, independent agencies, while they are subject to APA notice-and-comment, have not yet been treated as subject to enforceable regulatory review. Short of commanding independent agency compliance, presidents can use the bully pulpit to not encourage or to discourage their excesses.

- Executive Order 13610, Identifying and Reducing Regulatory Burdens addressed improved public participation and priorities in retrospective regulatory review.

In all, four of President Obama’s executive orders address over-regulation and rollbacks and the role of central review at OIRA. Their tone and intent can still help play a role in future bipartisan congressional efforts at regulatory oversight.

Trump Executive Orders on Regulation

President Donald Trump’s initial executive orders have considerably slowed the issuance of new rules and regulations to date, particularly those deemed economically significant. Trump began with a Regulatory Freeze Pending Review memorandum to executive branch agency heads from White House Chief of Staff Reince Priebus, which also applied to guidance documents, the latter a unique development. This was followed by E.O. 13771, Reducing Regulation and Controlling Regulatory Costs, the well-known order to require removal of at least two rules for every new one issued, and to cap regulatory costs, for which guidance documents could be counted toward fulfilment. Finally, E.O. 13777, Enforcing the Regulatory Reform Agenda, established Regulatory Reform Officers and Regulatory Reform Task Forces within agencies. (There had been versions of such entities in the Reagan and Clinton executive orders as well). Two separate memoranda from acting OIRA management with instructions for implementation of E.O. 13771 were also issued, affirming coverage of guidance as well as rules.

At this stage, in the absence of congressional action to further streamline the regulatory enterprise, a new executive order should more explicitly address agency guidance documents.

Originally published at Forbes.