Trump’s Tax Reform Plan Targets Middle-Class Tax Complexity

President Trump visited Missouri to talk about tax reform, stressing simplicity and middle-class tax relief and “plans to bring back Main Street by reducing the crushing tax burden on our companies and on our workers.”

Noting the elimination of “dozens of loopholes,” special interest carve-outs, and the reduction of brackets and rates that Congress achieved three decades ago, Trump said, “the foundation of our job creation agenda is to fundamentally reform our tax code for the first time in more than 30 years. I want to work with Congress, Republicans and Democrats alike, on a plan that is pro-growth, pro-jobs, pro-worker — and pro-American.”

We’re about to re-enter Obamacare repeal-style complexity and venom, but it’s important, I think, for the public to see the tax reform debate as something other than a campaign to benefit business. The U.S. does have comparatively high corporate tax rates. And the Econ 101 lesson on tax incidence shows that consumers pay much of the corporate tax, not the company.

It’s probable some Democrats would like to reform the tax code, especially come 2016, but the zero-tolerance of Trump, such as that seen at the Commonwealth Club when Sen. Diane Feinstein was barely favorable toward him, prevails.

But things can turn on a dime, as the response, likely bipartisan, to Hurricane Harvey may further show. And separately the controversial debt limit needs to be addressed no matter what (hopefully with parallel cuts in regulatory costs), and that debate will influence the trajectory of tax reform.

My broader point here though is is that taxation is just the beginning of the story when it comes to the complexity of regulatory compliance. The economy marinates in compliance burdens to service noble ends, but sometimes serve regulators instead. Trump characterized the Internal Revenue Service’s unfairness to the typical taxpayer like this:

The tax code is now a massive source of complexity and frustration for tens of millions of Americans.

In 1935, the basic 1040 form that most people file had two simple pages of instructions. Today, that basic form has one hundred pages of instructions, and it’s pretty complex stuff. The tax code is so complicated that more than 90 percent of Americans need professional help to do their own taxes.

This enormous complexity is very unfair. It disadvantages ordinary Americans who don’t have an army of accountants while benefiting deep-pocketed special interests. And most importantly, this is wrong.

There’s solid backup for what Trump’s talking about in terms of pubic burdens, even if some are disinclined to reckon with it, or if their allegiances require professing public disdain for corporations (one of the great democratizing forces in human history, but that’s another story).

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) agrees, I think, that Trump’s example of the IRS is a good one. In the course of a project I have of compiling examples of government proclamations that are not laws from Congress, nor even formal regulations from agencies, but instead “memoranda” and “guidance,” the IRS emerged as a leading “offender.”

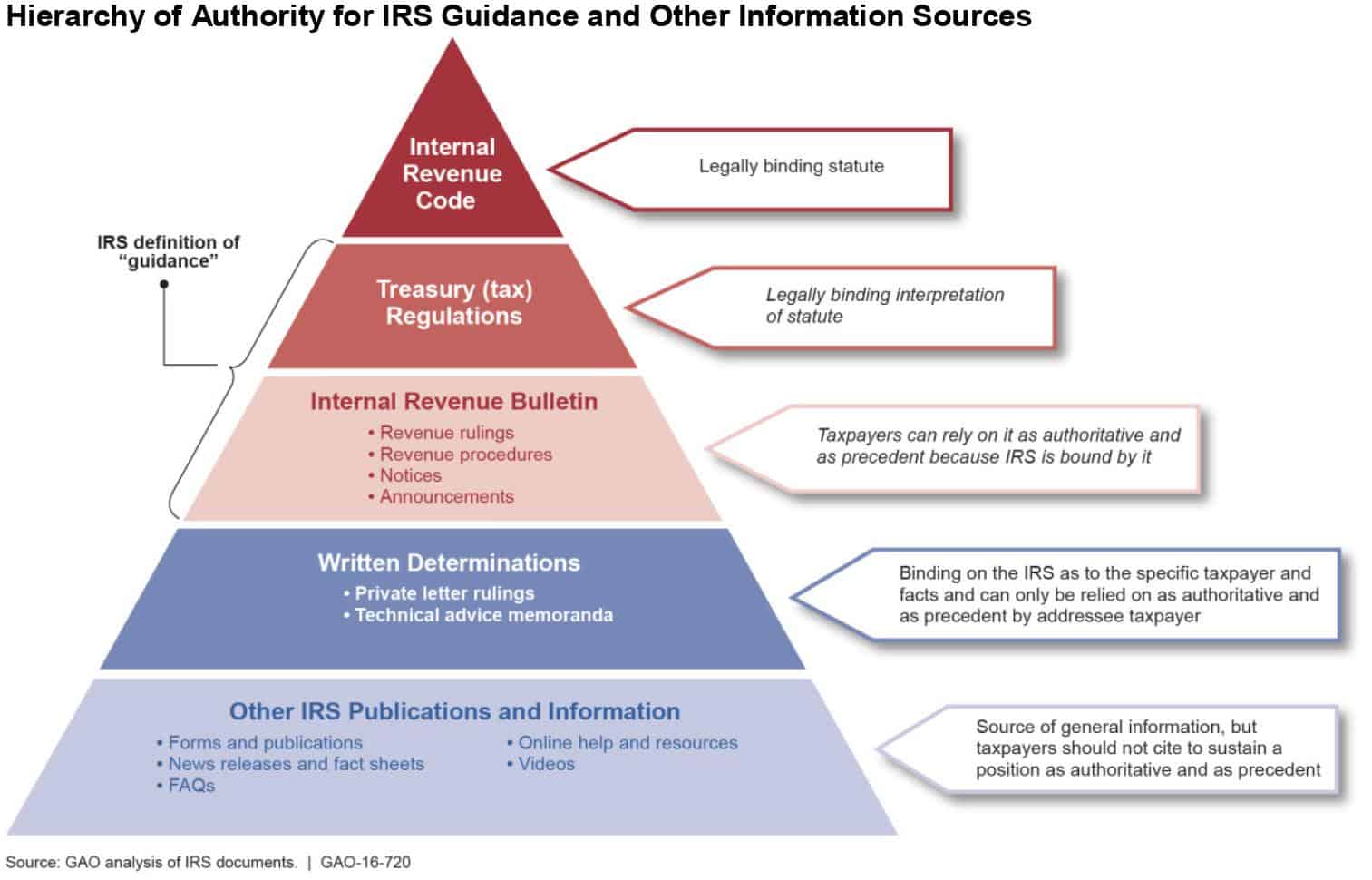

A September 2016 GAO report called “Regulatory Guidance Processes: Treasury and OMB Need to Reevaluate Long-standing Exemptions of Tax Regulations and Guidance,” looked at the Internal Revenue Service’s hierarchy of law, regulations, guidance, and explanatory material with respect to communicating interpretation of tax laws to the public.

It’s an eye-opener.

A pyramid diagram presented by GAO was topped by the Internal Revenue Code, as passed by Congress. Beneath that, in widening stages, one finds “Treasury Regulations,” “Internal Revenue Bulletins,” (IRB), “Written Determinations,” and “Other IRS Publications and Information.” The IRS regards the bulletins as generally authoritative, while determinations tend to apply to individual taxpayers.

That’s a lot of public guidance, difficult to absorb.

As the GAO explains:

Treasury and IRS are among the largest generators of federal agency regulations and they issue thousands of other forms of taxpayer guidance. IRS publishes tax regulations and other guidance in the weekly IRB. Each annual volume of the IRB contains about 2,000 pages of regulations and other guidance documents.

From 2013 to 2015, each annual Internal Revenue Bulletin edition contained some 300 guidance documents; back in 2002-2008, about 500.

When one sees such document proliferation from the IRS, an impartial observer might surmise the time for tax reform and simplification has arrived.

Likewise, when regulatory guidance multiplies that applies to various sectors—like finance, Internet, health care—one might similarly conclude the time has come for Congress to enact regulatory liberalization. Trump mentioned cutting the overall federal regulatory burden in the Missouri speech, too.

We knew it all along, but paying taxes also requires paying a lot of attention to regulations. In more ways than one, tax reform and regulatory reform go hand in hand.

Originally published to Forbes Online.