Chapter 16: Liberate to Stimulate: Framing an Agenda for Rightsizing Washington

It should be hard to enact bad law and regulation, not to get rid of them. A whole-of-government spending and regulatory agenda like the one happening now will require whole-of-liberty and whole-of-economy responses. In addition to dealing with a $31 trillion national debt, Congress must address federal regulations affecting manufacturing, finance, energy, technology, the environment, small businesses, families, and state and local governments.

“Liberate to stimulate” campaigns would remove barriers to entrepreneurship and hiring by shuttering bureaucracies, eliminating unneeded rules and programs, and liberalizing wherever possible. Those tasks would reinforce debt and deficit reduction before the next economic shock sparks another surge of spending and regulation.

The restoration campaign needs new urgency in the wake of Biden’s rule. Regulatory reforms that rely on agencies’ policing themselves within the limited restraints of the Administrative Procedure Act were already inadequate. Now, other pressures must come to bear.

A future executive branch could surpass Trump’s streamlining, while a future Congress could take a cue from the mid-1990s’ bipartisan passage of the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act, Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act, and the Congressional Review Act. These reforms happened because of pressure from governors and small businesses. Such agitations are likely to return in the wake of the past years’ legislative enactments. Congress should listen.

Policymakers ought not wait for the stars to align, but prepare now. Clearing out obsolete, decades-old statutes is a necessary task that requires laying a foundation. Congress should lay the groundwork to abolish, downsize, slash the budgets of, and deny appropriations to aggressive agencies, subagencies, and programs. It should also repeal or amend many of the enabling statutes that sustain the regulatory enterprise in the first place.

The Sherman and Clayton antitrust acts and antitrust apparatus should be repealed, along with the Federal Trade Commission and FCC Acts in their current form. OMB in progressive administrations protects regulation, rather than audits it. The overarching Administrative Procedure Act in the 21st century protects the administrative state and bureaucratic governance, rather than the norms of a limited constitutional republic. It is due for a hard reset.

Legislation must end crisis exploitation and abuses of national emergency declarations with sweeping privatization and localization of all federal government functions. This approach should include addressing increasingly regulatory entitlement spending and the Defense Department’s regulatory ambitions in areas like climate.

Perspective is key. Overdelegation to regulators is rampant and intolerable, but now a secondary concern. Administrative state reform cannot limit a government whose legislature is capable of transformations like the CARES Act, Families First Coronavirus Act, American Rescue Plan, Infrastructure Act, Innovation Act, and Inflation Act and supplements them all with recurring debt limit increases.

The 118th Congress can lay the groundwork for a systematic abolition campaign for statutes, agencies, and rules, as well as lesser moves, such as supervisory hearings on OMB’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs and the pursuit of Biden’s modernization order. Other oversight should prioritize preventing a progressive White House from weakening OMB’s Circular A-4 guidance on preparing regulatory impact analyses.

Regulatory impact analyses should have a disclaimer statement regarding any bias or exaggeration. Disclosure of unfunded mandates and of their significance is suspect and unaudited. Hearings should address what Christopher DeMuth and Michael Greve call “agencies of independent means,” whereby some agencies insulate themselves from Congress’s fiscal constraints by imposing fines and fees, effectively creating their own autonomous budgets and agendas. Hearings can also bring to light regulatory modernization initiatives in states, such as those of Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin and the state’s Office of Regulatory Management to impose regulatory cuts, expedite permitting, and increase cost analysis.

Congress can take a page from Biden and act unilaterally to enforce the regulatory controls now illegally ignored, such as OMB’s neglect of the aggregate and annual cost–benefit reports required by the Regulatory Right-to-Know Act, and the incomplete submission of rules and guidance to Congress and the GAO as required by the CRA. It should pass legislation requiring documentation of the reporting of covered rules to both the GAO and to Congress, for example, in the Federal Register, thereby improving the current incomplete presentation in the House and Senate communications that appear in the Congressional Record. Short of legislation, a committee or even one congressional office could call out rules that agencies neglected to report to the GAO or to the Hill, and publicize the yearslong delays in OMB’s cost–benefit report and the Information Collection Budget.

Congress often relies on must-pass appropriations and reauthorizations to push through wish-list initiatives. The dedicated legislation it does pass, like the Affordable Care Act and Dodd-Frank financial reform law, often spawns thousands of pages of regulations.

The alternative is for Congress to deny appropriations for carrying out regulatory programs. That is, Congress can use the power normally deployed for expanding regulation to streamline it instead. The ultimate funding lever is the debt ceiling, which may be among the last institutions capable of forcing downsizing.

Congress has already reintroduced several bills to restore some democratic accountability over unelected agency rule, some now waiting in the wings for more than two decades. One reform would have Congress address overdelegation by voting to approve major regulations before they can become binding. The first bill along these lines was the mid-1990s’ Congressional Responsibility Act proposal, which would have “prohibit[ed] a regulation from taking effect before the enactment of a bill comprised solely of the text of the regulation.” A version of this proposal now goes by the REINS Act, or Regulations from the Executive in Need of Scrutiny Act (H.R. 277 and S. 184), now reintroduced in the 118th Congress by Rep. Kat Cammack (R-Fla.) and Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.).

This step would ensure that Congress bears direct responsibility for explicit regulatory costs, as well as for the indirect costs noted in Box 2. Although some regulations’ gross benefits exceed gross costs under guidance like OMB Circular A-4, most rules never receive any cost or benefit analysis. Nor do agencies as a whole. This type of auditing would be useful for Congress’s annual agency appropriation decisions. Whether tabulated or unanimous consent votes, and whether rules are voted on alone or in bundles, members of Congress should go on record for or against every noteworthy or controversial regulation.

Another significant measure introduced in the 118th Congress is the Article I Regulatory Budget Act that amends the Congressional Budget Act and the Regulatory Flexibility Act to enlist multiple offices in needed regulatory analysis. The White House, CBO, GAO, and Bureau of Economic Analysis would calculate and cap costs of regulations and guidance documents, significant and nonsignificant, individually and in the aggregate. This bill would help bring regulatory costs aboveboard, similar to what is already done with tax receipts and outlays.

The All Economic Regulations Are Transparent (ALERT) Act would require monthly prenotifications on upcoming regulations, require disclosure of where regulations fit within cost tiers, and certify whether or not OMB reviewed a rule. Both these bills are sponsored by Rep. Bob Good (R-Va.). The Regulatory Accountability Act to enhance agency rulemaking processes has also been reintroduced, as has the Small Business Regulatory Flexibility Improvements Act.

Other bills in play include the Guidance Out of Darkness (GOOD) Act, to create a public portal where agencies would be required to post their guidance documents. Agencies often use these to issue new regulations or improperly influence policy while avoiding the required notice-and-comment rulemaking process. No Code of Federal Regulations–style database for guidance currently exists, and one must be skeptical that all regulation finds its way into the Federal Register. An official guidance portal to accompany the CFR and the U.S. Code would provide a more faithful portrayal of the federal government’s reach and aid in setting up the additional restraints needed to confront the progressive agenda.

The Guidance Clarity Act would require that documents attest to their nonbinding nature and add transparency and accountability to unfunded mandates. Legislation establishing a Regulatory Reduction Commission or task force for routine review and rule purging—modeled after the 1990s Base Realignment and Closure Commission—is another important reform. The latest version of this reform is Sen. Mike Lee’s (R-Utah) LIBERATE Act in the 117th Congress.

Legislation requiring sunsetting of rules, and the codifying elements of Trump’s executive order policies, such as the one-in, two-out rule for new regulations, guidance, and memoranda, is likely. Subjecting independent agencies to the regulatory review from which they are now exempt has enjoyed bipartisan support.

At the agency-restraint level, bills have been introduced to allow states to regulate energy extraction operations on the federal lands within their own borders; reform the Endangered Species Act; prevent an FCC reinstatement of the Fairness Doctrine; ban COVID-19 vaccination requirements; require concealed carry reciprocity across states; and remove certain rifles and guns from the regulatory definition of “firearm.”

Some mechanism for government downsizing needs to be automatized. The foregoing bills do address foundational deconstruction of the administrative state’s excesses. That still may not be enough. One solution is an “Office of No” that would replace or supplement the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. Its sole tasks would be to make the case against new and existing regulations and to facilitate ongoing sunsetting and streamlining.

Legislation with more modest goals can still be very helpful at facilitating more fundamental reforms. Simplifying the confusing regulatory nomenclature (major, significant, economically significant) can help. So can limiting agencies’ rulemaking to what they have already announced in the Unified Agenda and better distinguishing in the Unified Agenda and Federal Register between rules that are regulatory and those intended to be deregulatory. Reconciling recordkeeping across various government databases—such as direct mapping between the Unified Agenda, the GAO, and the Federal Register, as well as within the Federal Register’s own inconsistent internal databases—would boost disclosure. Before Biden eliminated Trump’s guidance document portals, reporting of guidance was never incorporated in the Federal Register but could have been.

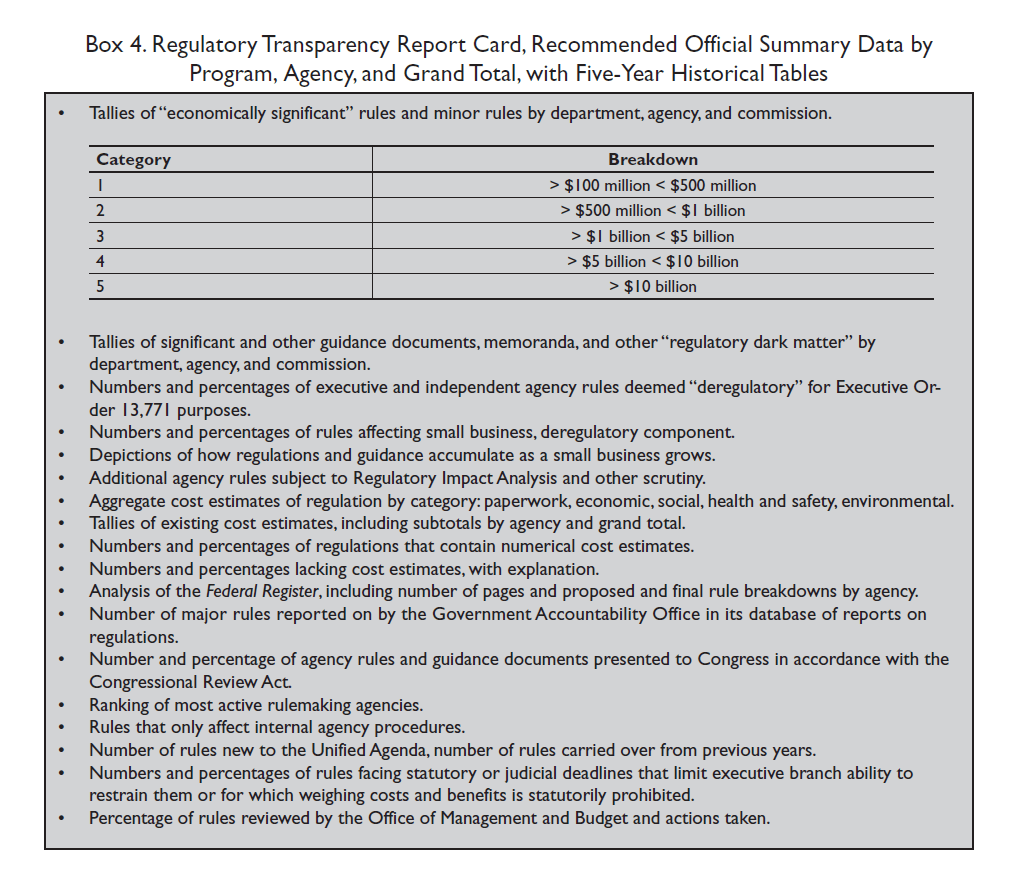

Online databases like Regulations.gov make it far easier than in pre-Internet times to learn about regulatory trends and acquire information on rules. More can be done to make material more complete, accessible, and user-friendly. Relevant regulatory data should be compiled and summarized for the public in annual report cards. The suggested components of such a regulatory transparency report card that appear in Box 4 could be officially summarized in charts in the federal budget, the Unified Agenda, and the Economic Report of the President; on Regulations.gov; as part of a resurrection of the defunct Regulatory Program of the U.S. Government; or elsewhere.

One cannot look at the daily Federal Register and get a sense of rules that are being cut or which agencies are adding the most rules, nor of which ones of a flow of rules might be reducing burdens rather than expanding them. These should be classified separately in the Federal Register. In addition to revealing burdens, impacts, and trends, a report card can help reveal what one does not know about the regulatory state—such as, for example, the percentage of rules for which agencies failed to quantify either their costs or their benefits.

Current reporting distinguishes poorly between rules and guidance documents affecting the private sector and those affecting internal government operations. Providing historical tables for all elements of the regulatory enterprise would prove useful to scholars, third-party researchers, members of Congress, and the public. By making agency activity more explicit, a regulatory transparency report card would help ensure that policymakers take the growth of the administrative state seriously, or at least afford it some weight along with fiscal concerns.

The accumulation of regulatory guidance documents, memoranda, and other regulatory dark matter calls for greater disclosure and inventorying than exists now, and any report card would need ongoing improvement. Currently, by imposing requirements on the private sector instead of spending, government can expand almost indefinitely without explicitly taxing anybody one extra penny.

Pressure from states could eventually prompt Congress to address regulation. If Congress does not act, states could step in. The Constitution’s Article V provides for states to check federal power. Many state legislators have indicated support for the Regulation Freedom Amendment, which reads, in its entirety: “Whenever one quarter of the members of the U.S. House or the U.S. Senate transmit to the president their written declaration of opposition to a proposed federal regulation, it shall require a majority vote of the House and Senate to adopt that regulation.” That amounts to a version of the REINS (Regulations from the Executive in Need of Scrutiny) Act for the rule in question.

When Congress ensures transparency and disclosure and assumes responsibility for the growth of the regulatory state, the resulting system will be one that is fairer and more accountable to voters. Another pressing concern today is the executive branch’s own arrogation of power to itself, a phenomenon that has escalated since 2020.

The greater questions are over not merely the role and legitimacy of the administrative state, but the proper scope of federal power to regulate. How one answers those questions will determine whether something resembling a constitutional republic will continue.