CEI Comments on California’s Advanced Clean Cars II Waiver Request

Thank you for the opportunity to comment[1] on the California Air Resources Board’s (CARB’s) request for a waiver under Section 209(b) of the Clean Air Act (CAA) to implement California’s Advanced Clean Cars II (ACC II) Regulations.[2]

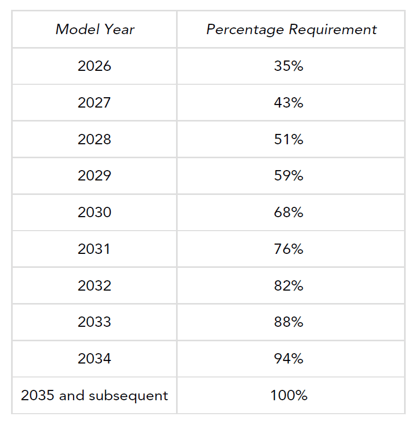

Among other program components, ACC II establishes Zero-Emission Vehicle (ZEV) sales mandates for model years 2026-2035 and later. The mandates are calibrated as annual percentages of each automaker’s light-duty vehicle sales in the State. The ZEV standards increase from 35 percent in 2026 to 100 percent in 2035 and later. In other words, the ZEV program progressively bans the sale of new gasoline- and diesel-powered cars and light trucks over a 10-year period.[3]

The ACC II program also include greenhouse gas (GHG) emission standards for new internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles. The ACC II Regulations do not substantively change CARB’s existing GHG standards for light- and medium-duty vehicles through model years 2025 and beyond. Automakers continue to have the option to comply with CARB’s tailpipe standards by complying with EPA’s motor vehicle GHG standards.

My comments address the legality of California’s ZEV program and tailpipe GHG standards. Specifically, the comments focus on the California standards’ incompatibility with Section 32919(a) of the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA).

The main takeaways are as follows:

- EPCA 32919(a) preempts the tailpipe GHG standards and ZEV mandates for which California seeks a waiver. Those policies are legally invalid. EPA should decline to grant the ACC II waiver.

- EPA and NHTSA’s September 2019 SAFE 1 Rule clearly and correctly explains how EPCA 32919 preempts California’s tailpipe GHG standards and ZEV mandates.

- EPA and NHTSA’s SAFE 1 repeal proceedings in 2021 and 2022 “entirely fail to address an important aspect of the problem,” namely, SAFE 1’s EPCA preemption analysis. The agencies’ repeal proceedings are arbitrary and capricious.

- EPA’s claim that California has the “broadest possible discretion” to adopt its own vehicle emission standards comes from report language, not the statute. There is a shocking disproportion between the actual discretion upheld by the D.C. Circuit based on that language, and California’s current regulatory ambition to ban gasoline- and diesel-powered cars.

- Congress never envisioned that EPA would use 209(b) to authorize States to deny tens of millions of Americans the freedom to purchase vehicles of their choice. The current waiver proceeding raises major questions, conflicting with West Virginia v. EPA.

- Although EPA is not required to address constitutional concerns in a waiver proceeding, neither is it forbidden to do so. Forthright consideration of EPCA preemption could help restore the due process rights automakers traded away under duress in May 2009 when confronted with the prospect of a market-balkanizing fuel-economy patchwork.

Background

In September 2019, EPA and NHSTA finalized Part 1 of the Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient Vehicles Rule (SAFE 1). NHTSA made the following determination. EPCA Section 32919(a) expressly and categorically preempts state laws and regulations “related to” fuel economy standards.[4] State policies regulating or prohibiting tailpipe carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions are directly or substantially related to fuel economy standards. Hence, EPCA 32919(a) preempts California’s tailpipe GHG standards and ZEV mandates.[5]

In the same SAFE 1 rulemaking, EPA made the following complementary determination. CAA 209(b) states that EPA “shall” not grant a waiver if California “does not need such State standards to meet compelling and extraordinary conditions.” The phrase “compelling and extraordinary conditions” refers to the State’s meteorology (thermal inversions), topography (pollution concentrating basins), and high concentration of automobiles—factors chiefly responsible for the State’s air pollution problems. In contrast, those factors have no discernible influence on the anthropogenic greenhouse effect. Moreover, California’s tailpipe GHG standards and ZEV mandates would not achieve any detectable mitigation of global warming or other climate impacts. Hence, California does not need such standards.[6]

In sum, in SAFE 1, NHTSA determined that California’s tailpipe GHG standards and ZEV mandates are null and void, and EPA revoked the 2013 ACC I waiver authorizing California to implement those policies.[7]

In May 2021, NHTSA proposed to repeal its portion of SAFE 1, and finalized repeal in December.[8] In April 2021, EPA convened a reconsideration of its withdrawal of the 2013 ACC I waiver, and in March 2022 issued a Notice of Decision reinstating the ACC I waiver.[9] CARB’s ACC II waiver request repeatedly cites EPA’s Notice of Decision legal analysis as confirming CARB’s interpretation of CAA 209(b) and its judgment that California needs its tailpipe GHG standards and ZEV mandates to meet compelling and extraordinary conditions.

My earlier comments of July 6, 2023 discuss whether “such State standards” in CAA 209(b) refer to California’s separate vehicle emissions program or just the particular standards for which California seeks a waiver, whether collateral reductions in refinery criteria pollutant emissions establish California’s “need” for ZEV mandates, whether California’s climate change impacts are “compelling and extraordinary conditions” under CAA 209(b), and whether EPCA 32919(a) preempts those policies.[10]

The present comments focus solely on EPCA preemption, because EPA’s request for comments on reconsideration Notice of Decision do not adequately address it. Like NHTSA’s proposed and final SAFE 1 repeal rules, EPA’s request for comments and Notice of Decision do not even summarize SAFE 1’s EPCA preemption argument, much less rebut it on the merits.

Accordingly, the next section of these comments restates the clear logic of SAFE 1’s EPCA preemption analysis. The bottom line conclusion may be stated as follows: EPCA 32919(a) voided California’s tailpipe CO2 standards and ZEV mandates before California could request, or EPA grant, a waiver of Clean Air Act preemption. EPCA 32919(a) turned those policies into legal phantoms—mere proposals with no legal force or effect.

EPCA preemption is clear (expressly stated), broad (prohibiting policies merely “related to” fuel economy standards), and categorical (non-waivable and allowing no exceptions). A waiver of Clean Air Act preemption cannot give legal force and effect to emission standards EPCA automatically nullified.

EPCA Preemption

EPCA 32919(a) states:

When an average fuel economy standard prescribed under this chapter is in effect, a State or a political subdivision of a State may not adopt or enforce a law or regulation related to fuel economy standards or average fuel economy standards for automobiles covered by an average fuel economy standard under this chapter.[11]

Section 32919(a) expressly prohibits state policies merely “related to” fuel economy standards. The statute envisions no exceptions, does not even allow equivalent or identical state regulations, and provides no authority to waive preemption of state laws or regulations. That means EPCA 32919(a) is not a “general rule of preemption” requiring subsequent regulatory adjudication to fine tune the boundaries of permissible state action. It is difficult to imagine a more sweeping, absolute, and definitive preemption statute.[12]

Federal preemption statutes derive their authority from the Supremacy Clause (Article VI, Clause 2), which states:

This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.

As the Supreme Court explained, “It is basic to this constitutional command that all conflicting state provisions be without effect.”[13] That means any conflicting state policy is void ab initio—from the moment the policy is adopted or enacted, not when a court later declares it so.[14]

California’s tailpipe CO2 standards are physically and mathematically “related to” fuel economy standards. An automobile’s CO2 emissions per mile are directly proportional to its fuel consumption per mile. Thus, regulating grams CO2 per mile also regulates fuel consumption per mile, and vice versa.[15]

Fuel economy and tailpipe CO2 standards will remain mathematically convertible as long as affordable and practical onboard carbon capture technologies do not exist.[16] Fuel economy and tailpipe CO2 emissions are “two sides (or, arguably, the same side) of the same coin.”[17] Since the start of the corporate average fuel economy (CAFE) program in 1975 and for the foreseeable future, all design and technology options for reducing tailpipe CO2 emissions, such as aerodynamic streamlining, low rolling resistance tires, and hybridization, are fuel-saving strategies by another name.

The Congress that enacted EPCA in 1975 understood the scientific relationship between CO2 emissions and fuel economy. That is why Congress directed the Department of Transportation to use EPA’s fuel economy calculation and testing procedure, which is to measure tailpipe emissions of CO2 and other hydrocarbons.[18]

ZEV mandates are substantially related to fuel economy standards.[19] As ZEV mandates tighten, fleet average fuel consumption per mile decreases, i.e., fleet average fuel economy increases. Conversely, as EPA’s recently proposed model year 2027-2032 tailpipe CO2 standards reveal, if fuel economy requirements tighten beyond a certain point, automakers cannot comply without selling more ZEVs and fewer ICE vehicles.[20]

Furthermore, because California’s tailpipe GHG standards and ZEV mandates interfere with the national fuel economy system Congress created, they are also implicitly preempted. The interference takes two main forms.

First, California’s policies revise regulatory determinations Congress authorized NHTSA to make. EPCA[21] and D.C. Circuit case law[22] require NHTSA to weigh and balance five factors when determining CAFE standards: technological feasibility, economic practicability, the effect of other federal emission standards on fuel economy, the national need to conserve energy, and the impact of fuel economy standards on occupant safety. California is not bound by those factors, and is free to subordinate them to climate ambition.

Only by sheer improbable accident would CARB, when prescribing tailpipe CO2 standards, weigh and balance such factors the same way NHTSA does when prescribing fuel economy standards. Indeed, there is no policy rationale for elevating CARB from fuel economy stakeholder to decisionmaker unless its technical assessments and regulatory priorities differ from NHTSA’s.

Second, California’s ZEV mandates directly conflict with the CAFE program. ZEV standards are technology-prescriptive, requiring automakers to sell increasing percentages of vehicles powered by batteries or fuel cells. CAFE standards are supposed to be technology-neutral. Manufacturers are “not compelled to build vehicles of any particular size or type,” EPA said during the Obama administration. Rather, each manufacturer has its own fleet-wide performance standard that “reflects the vehicles it chooses to produce.”[23] Or, at least that was how the program worked until EPA started setting tailpipe CO2 standards that force fleet electrification.

By law, NHTSA’s standards are to be set in light of technological feasibility and economic practicability. The ZEV program is not similarly constrained. For example, in 1998, CARB required ten percent[24] of new car sales to be ZEVs by 2003—a mandate neither feasible nor affordable. The market share of ZEV sales in California were still below 1 percent as late as 2011.[25]

EPCA as amended prohibits NHTSA from considering the market penetration of alternative vehicles, such as ZEVs, when prescribing fuel economy standards.[26] In other words, CAFE standards may not be so stringent that compliance is impossible unless ZEV sales increasingly displace ICE vehicle sales. California’s ZEV program aims to do precisely that.

Neither NHTSA nor EPA specifically address any of the foregoing points in their SAFE 1 repeal proceedings. EPA’s Notice of Decision claims that NHTSA’s final SAFE 1 repeal rule discusses “the much debated and differing views as to what is a ‘law or regulation related to fuel economy.’”[27] In fact, NHTSA does nothing more than assert a newfound and unexplained agnosticism. To reiterate, NHTSA’s final repeal rule provides no specific reasons for “withdrawing” the SAFE 1 preemption argument that the agency declines to even summarize.

In short, both EPA’s and NHTSA’s SAFE 1 repeal proceedings are arbitrary and capricious because agencies “entirely fail to consider an important aspect of the problem,” [28] namely, SAFE 1’s core statutory argument.

EPA treats EPCA 32919(a) as implicitly repealed by CAA 209(b0 but fails to defend or even acknowledge its position. Moreover, EPA’s understanding of CAA 209(b) is untethered to the text of the provision, as discussed in the next section.

Report Language Does Not Trump Statutory Language

EPA’s Notice of Decision gives the impression that SAFE 1 cannot possibly be lawful because it conflicts with Congress’s intent in CAA 209(b). Congress intended for EPA “to afford California the broadest possible discretion in selecting the best possible means to protect the health of its citizens and the public welfare.”[29] The Notice of Decision quotes that phrase, in whole or part, 11 times. CARB’s ACC II waiver request support document similarly contends that CAA 209(b) gives CARG “the broadest possible discretion in reducing air pollution and its impacts.”[30]

The Notice of Decision cites two cases where the D.C. Circuit uses the same language in rendering decisions favorable to CARB: Ford Motor Co. v. EPA[31] and Motor and Equipment Mfrs. Ass’n, v. EPA (MEMA I.)[32]

Similarly, the Notice of Decision in repeatedly asserts that Congress intended to allow California to be a “pioneer” (nine times) and “laboratory” (18 times) in setting new vehicle emissions standards and developing control technology. The point seems to be that SAFE 1 would frustrate Congress’s legislative intent. Both of the aforementioned D.C. Circuit cases invoke the “pioneer” language, and MEMA 1 also invokes the “broadest possible discretion” language.

However, the policy significance of that language and the precedential force of those decisions are less than one might suppose. In the first place, the “broadest possible expression,” “pioneer,” and “laboratory” language is nowhere to be found in CAA 209. It comes from House and Senate reports.[33]

Late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia famously cautioned against elevating report language above statutory text as a guide to interpreting the law. Many members do not read the bills they pass, and fewer have input into report language. Conference or committee leaders may use report language to advance agendas unknown to or opposed by some who voted for the bill, or to shape future decisions by agencies or courts.

The following excerpt from Scalia’s book, A Matter of Interpretation, is suitable for framing:

Ironically, but quite understandably, the more courts have relied upon legislative history, the less worthy of reliance it has become. In earlier days, it was at least genuine and not contrived—a real part of the legislation’s history, in the sense that it was part of the development of the bill, part of the attempt to inform and persuade those who voted. Nowadays, however, when it is universally known and expected that judges will resort to floor debates and (especially) committee reports as authoritative expressions of “legislative intent,” affecting the courts rather than informing the Congress has become the primary purpose of the exercise. It is less that the courts refer to legislative history because it exists than that legislative history exists because the courts refer to it. One of the routine tasks of the Washington lawyer-lobbyist is to draft language that sympathetic legislators can recite in a prewritten “floor debate”—or, even better, insert into a committee report.[34]

More pertinently, those snippets of report language quoted by the D.C. Circuit in 1979 do not support the expansive regulatory agenda on which CARB embarks. In MEMA 1, the “broadest discretion” CARB lawfully exercised was to adopt a weaker-than-federal carbon monoxide (CO) standard in order to implement a stronger-than-federal nitrogen oxides (NOX) standards. In Ford Motor Co., CARB’s “pioneering” consisted of revising manufacturer warranties to encourage the development of more durable emission control devices. There is a shocking disproportion between the “broadest possible discretion” upheld in MEMA 1 and CARB’s plan to ban ICE vehicle sales on a 10-year timetable.

Major Questions

In West Virginia v. EPA,[35] the Supreme Court held that the agency’s CO2 emission standards for existing fossil-fuel powerplants, the so-called Clean Power Plan (CPP), aimed to “substantially restructure the American energy market,” entailing a “transformative expansion” of the agency’s regulatory authority. Moreover, the Court found that the CPP’s purported statutory basis, CAA Section 111(d), does not come “close to the sort of clear authorization required” to “delegate authority of this breadth to regulate a fundamental sector of the economy.”[36]

Parallels between the CPP and the ACC II waiver readily come to mind. Examples:

[CAA 209(b) does not come “close to the sort of clear authorization required” to “delegate [either to EPA or CARB] “authority of this breadth to regulate a fundamental sector of the economy.”

Indeed, granting the ACC II waiver would give CARB, a state bureaucracy unaccountable to Congress, a “hitherto unmentioned power” to “substantially restructure the American [transportation and] energy market.”[37]

Granting the waiver would entail a “transformative expansion” of California’s regulatory authority, empowering it to determine “how much [gasoline- and diesel-based] transportation there should be over the coming decades,”[38] and even whether such [ICE vehicles] “should be allowed to operate.”[39]

Granting the waiver would end an “earnest and profound debate across the country” about national climate policy, a matter of “great political significance.”[40]

Granting the waiver would empower California and allied states would restrict millions of Americans’ freedom to purchase the vehicles that best meet their needs even though “Congress has never come close to amending the Clean Air Act to create such a program.”[41]

CAA Section 209(b) Is Not a Gag Rule

EPA should forthrightly address the SAFE 1 Rule’s preemption argument, which is both textual, technical, and constitutional. However, EPA argues that in 209(b) waiver proceedings it may only consider the provision’s three decision factors, and constitutional propriety is not among them. However, this gag rule interpretation of 209(b) goes beyond the D.C. Circuit’s ruling in MEMA 1.

The court stated that, “Nothing in section 209 requires [EPA] to consider the constitutional ramifications of the regulations for which California requests a waiver,” not that EPA is forbidden to do so. Whether EPA may consider constitutionality is left open: “We need not decide here whether the Administrator is authorized to deny a waiver on the ground that the proposed California regulations are on their face violative of the Constitution.”[42]

Note, too, the court assumed petitioners could always assert constitutional claims in the D.C. Circuit even if such claims were never considered in a waiver proceeding. That is incorrect. In May 2009, under a “vow of silence,”[43] Obama climate czar Carol Browner negotiated an agreement between California, EPA, NHTSA, automakers, and autoworkers. The agreement elevated CARB from fuel-economy stakeholder to fuel-economy decisionmaker. As part of the deal, automakers agreed to surrender their rights to challenge CARB’s GHG regulations on EPCA preemption grounds.[44] In return, CARB agreed to deem compliance with EPA’s GHG standards as compliance with its own. That suspended the threat that CARB, in tandem with CAA section 177 states, would unleash a market-balkanizing fuel-economy “patchwork.”[45] However, CARB reserved the right to walk away from the deal if future administrations backslide from the 2017-2025 CAFE and GHG standards contemplated as of 2011.[46]

It is time to restore automakers’ due processes rights. Candidly addressing SAFE 1’s preemption argument, rather than treating it as taboo, would certainly help start a more robust public conversation.

Conclusion

Granting the ACC II waiver will only entrench the regulatory overreach of a state agency bent on settling national questions of public policy without clear congressional authorization.

Congress may have been fine with EPA waiving preemption for the ZEV program when it was nothing more than a “laboratory” experiment in one state. But the program is now poised to deny tens of millions of Americans their freedom to choose the types of vehicles that best suits their needs. There is no evidence, textual or historical, that Congress intended for CAA 209(b) to establish CARB as the nation’s transformational industrial policy czar. EPA should decline to grant the ACC II waiver.

Secondly, and subordinately, given EPA and NHTSA’s previous recent adoption of SAFE 1 and the direct relevance of its preemption analysis, the agencies should stop evading the well-grounded constitutional concerns expressed by SAFE 1. Refusing to address that “important aspect of the problem” is arbitrary and capricious.

Sincerely,

Marlo Lewis, Ph.D. Senior Fellow, Competitive Enterprise Institute, [email protected]