CEI’s Comments to the Department of Transportation on Ensuring Lawful Regulation

Dear Mr. Cohen:

The Department of Transportation’s above-captioned request for information seeks “public comment on how best to ensure lawful regulation and to achieve meaningful burden reduction while continuing to achieve DOT’s legal obligations, safety mission, and regulatory objectives.” 90 Fed. Reg. 14,593, 14,593 (Apr. 3, 2025). It does so in compliance with Executive Order 14219, “Ensuring Lawful Regulation and Implementing the President’s ‘Department of Government Efficiency’ Deregulatory Agenda.” 90 Fed. Reg. 10583 (Feb. 25, 2025). That order requires agencies to identify regulations that fall within seven categories of regulations that undermine the national interest. The request for information asks, “Are there any regulations or guidance commenters can identify that fall within the seven categories outlined in Executive Order 14219?” 90 Fed. Reg. at 14,595.

The answer is yes. One of the seven categories is “Unconstitutional regulations and regulations that raise serious constitutional difficulties.” This comment will identify regulations of the Department of Transportation (Department) that raise serious constitutional difficulties and will propose amendments to correct those difficulties.

Many of the Department’s regulations raise serious constitutional difficulties that might not have been apparent at the time of their adoption. But in the light of SEC v. Jarkesy, 603 U.S. 109 (2024), those difficulties should be addressed now.

“SEC v. Jarkesy carries generational significance.” William Yeatman, The Past, Present, and Future of Administrative State Adjudication, 2024 Cato Sup. Ct. Rev. 57, 57. The case interpreted the Seventh Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which provides in pertinent part, “In Suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved. . . .” Jarkesy held that a statutory claim that is in the nature of an action at common law implicates the Seventh Amendment. 603 U.S. at 122. Congress may not remove an action involving private rights from the protection of the Seventh Amendment and assign it to an agency for decision. Id. at 127.

To determine whether a statutory claim is in the nature of an action at common law, the cause of action and the remedy it provides should be considered. The remedy is the more important of the two considerations because some causes of action sound in both law and equity. Id. at 122-23.

A governmental action seeking a monetary penalty as the remedy is an action for debt and as such is in the nature of an action at common law. Tull v. United States, 481 U.S. 412, 418-22 (1987); United States v. Regan, 232 U.S. 37, 47 (1914). A suit for a civil penalty has been regarded as analogous to a common law action in debt. Tull v. United States, 481 U.S. at 418-20. A civil penalty is also a type of remedy at common law that could be enforced only by courts of law. A penalty is legal if it is punitive rather than compensatory. Jarkesy, 603 U.S. at 123; Tull, 481 U.S. at 422. The Court in Jarkesy found that “the civil penalties in this case are designed to punish and deter, not to compensate.” 603 U.S. at 125. That finding was decisive in the Court’s conclusion that the Seventh Amendment applied.

The Court added that its conclusion that the Seventh Amendment applied to the case was confirmed by the close relationship between the claims brought by the Securities and Exchange Commission and common law fraud. Id. The Court further held that the public rights exception to the Seventh Amendment requirement does not extend to suits in the nature of an action at common law. Id. at 138-40.

As noted, under Jarkesy the first consideration is the remedy. Many laws enforced by the Department authorize civil penalties that do not reimburse anyone. Their purpose is punitive. “[T]he remedy is all but dispositive.” Id. at 123. The second consideration is the nature of the cause of action. Some of the actions for civil penalties that the Department may bring are clearly in the nature of common law actions for trespass, negligence, or fraud. In other cases the analogy is not as close. “But ambiguity on this second consideration points us back to the ‘more important’ first consideration—remedy.” AT&T, Inc. v. FCC, No. 24-60223, 2025 WL 1135280 at *6 (5th Cir. Apr. 17, 2025) (quoting Jarkesy, 603 U.S. at 123). In contravention of the Seventh Amendment, nearly all of the Department’s actions for civil penalties may be tried administratively. Frequently, the law authorizes a civil action to collect a penalty after it has been imposed administratively without a jury.

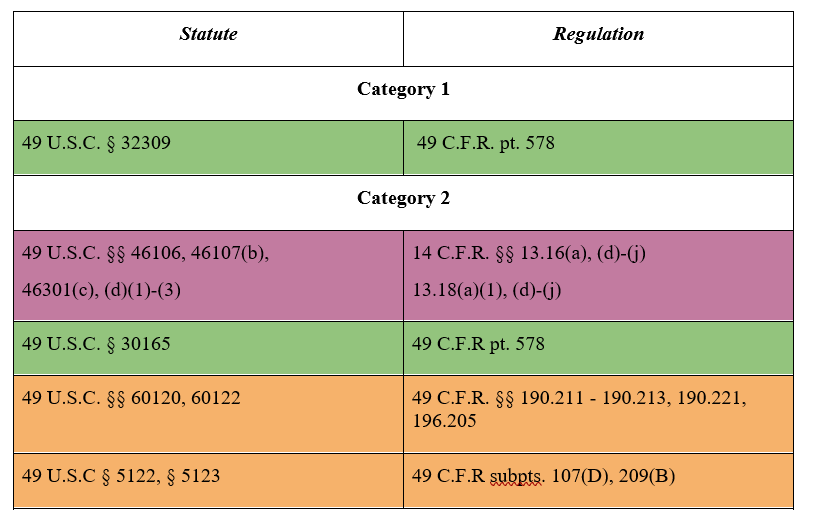

In most cases the conflicts between the Department’s regulations and the Seventh Amendment can be corrected through rulemaking. The statutes within the Department’s jurisdiction that authorize civil penalties fall into three categories.

In the first category, neither the statute nor the regulations specify a mode of recovery. General laws of judicial procedure enable the Department to fill this gap in compliance with Jarkesy: “Whenever a civil fine, penalty or pecuniary forfeiture is prescribed for the violation of an Act of Congress without specifying the mode of recovery or enforcement thereof, it may be recovered in a civil action.” 28 U.S.C. § 2461(a). United States attorneys have the duty to prosecute in their districts all civil actions for the government. Id. § 547(2). Thus, in this case a rule should be adopted to require judicial adjudication of civil penalties. In other words, the rule should provide that the secretary may request the attorney general to commence a civil action to recover civil penalties in an appropriate U.S. district court.

In the second category, statutes authorize judicial adjudications assessing (not merely collecting) civil penalties or authorize both judicial and administrative adjudications of civil penalties, and the applicable regulations permit or require actions to be tried administratively. In these cases, the regulations should be amended to require judicial adjudication of civil penalties.

Conflicts in the third category cannot be so easily resolved. In the third category, the statute authorizes violations to be adjudicated administratively and does not authorize them to be adjudicated judicially. The Department cannot change the statute, but in these cases the applicable rules should be revised to state that the Department will not seek civil monetary penalties for violations of such laws until Congress amends the laws[1] or the Administrative Procedure Act to authorize enforcement by civil actions in district court. Otherwise, only parties who lack competent representation will incur fines, and parties with competent representation will waste time and money vindicating their rights.

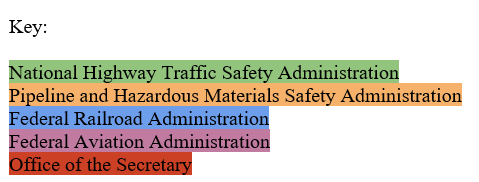

For each of the categories, the chart on the following page sets forth statutes authorizing civil penalties paired with the applicable regulations—to the extent that it is possible to trace what regulations implement a particular statutory authorization of civil penalties. The Department should begin the process of amending the regulations listed under categories 1 and 2.

Language that Congress could use for this purpose is found in 49 U.S.C. § 32308(e): “A civil action under this section may be brought in the judicial district in which the violation occurred or the defendant is found, resides, or does business. Process in the action may be served in any other judicial district in which the defendant resides or is found. A subpoena for a witness in the action may be served in any judicial district.” See also 49 U.S.C. §§ 11901(f), 14901(f).

On behalf of the Competitive Enterprise Institute, I thank you for the opportunity to assist the Department in identifying regulations that can be revised to better achieve the Department’s regulatory objectives in a manner consistent with the Constitution.

Cordially yours,

David S. McFadden

Attorney

COMPETITIVE ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE