A Free Market is the Best Medicine

Why government should not interfere with the rapid changes in the pharmacy industry

Introduction

The pharmaceutical supply market is seeing extraordinarily high levels of innovation and consumer-benefiting evolution. The combination of a competitive market for generic drugs, rapid technological advancement driven by internet access, delivery infrastructure, and corporate logistical improvements has generated a series of delivery structures that allow unprecedented access and convenience for consumers. Americans have never had so many access points to obtain their medication as they do today, and more are added regularly. Pharmacies are still the primary source for prescription drugs, but online and mail-order options are becoming more common.

Recently, government regulators have expressed concern with this rapid and organic progression. Some policymakers have decided it is necessary to interfere in the market and try to direct it to predetermined outcomes. In many cases, the ultimate policy implemented has been minor and focused on transparency, but a growing number of states are considering more intrusive and harmful regulations, such as banning certain ownership structures and delivery methods based on who is providing the service.

At the core of these policies is a concern over one of the layers of the pharmaceutical supply chain which is largely invisible to the consumer, yet significant in the market — pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). Policymakers and other participants in the pharmaceutical market are skeptical of PBMs’ role and are concerned PBMs will use market power to hurt competition and consumers. Consequently, some policymakers are trying to preclude PBMs from operating pharmacies, whether they are retail pharmacies that customers can drive to or mail-order pharmacies that deliver drugs directly to customers. These proposals are misguided and ill-conceived. Policymakers should reject them and let consumers drive the decisions.

Traditional pharma goes online

GoodRx has received substantial attention in the past 10 years and has arguably led to a restructuring of much of the pharmacy industry’s dynamics. The GoodRx platform facilitates shopping at pharmacies and works by comparing the prices that PBMs have negotiated with different pharmacies for different drugs and providing the consumer with the lowest PBM price for each pharmacy. This allows the consumer to shop for prescription drugs quickly and efficiently and balance lower prices with convenience. It is not unlike an app that quickly shows a map of gas prices allowing drivers to purchase gas for the lowest price at the most convenient location for them.

GoodRx estimated that in 2024, 30 million people used its platform to purchase prescription drugs, a 20 percent increase from 2023, providing a resource for Americans regardless of where they obtain insurance. It helps the uninsured afford vital drugs but also helps 25 million people who have insurance to save money. Because these people must pay completely out-of-pocket, the full price of the drug via GoodRx is less than their copay with insurance.

GoodRx provides competitive pressure between PBMs to keep prices low. PBMs have an incentive to participate because they get both the volume and an administrative fee, which leads them to compete to offer the lowest price. Currently, 70,000 pharmacies accept GoodRx customers. In 2023, GoodRx saved its 25 million customers $15 billion.

GoodRx not only incentivized competitors to offer the same service but also caused PBMs to offer their own discount card programs that perform a similar function. The PBMs’ versions offer covered beneficiaries an easy way to compare their price through insurance to an uninsured price to ensure they received the best value. The multitude of options has been addressed at the opposite end of the process as well. Physicians writing prescriptions face a daunting set of products to choose from. Technology now allows them to know which drugs are available to individual patients according to their insurance and whether the drug is generic or brand-name. This, in turn, allows the physician to quickly prescribe the appropriate treatment at the lowest cost without worrying about creating a logistical problem for the patient. This service, known as real-time prescription benefit, is one of the many operations silently running in the background that utilizes information from the insurer and the PBM to help reduce prices and smooth out the process. Studies have shown that it improves adherence to medications and lowers costs.

Online pharmacies bloom

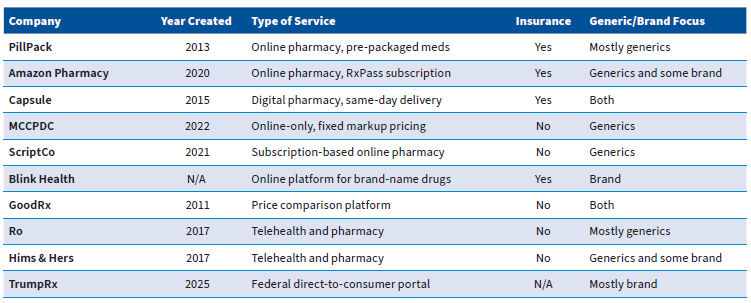

Over the past two decades, the internet has revolutionized the way people shop for goods and services, including pharmaceuticals. Before then, online pharmacies did not exist. Today, they are ubiquitous, including Amazon Pharmacy, as well as Walgreens and CVS, which have launched online platforms in addition to maintaining their physical stores.

Among the new collection of online-only retailers, several companies began to focus on prescription drugs. Many of the online pharmacies are innovative. For example, PillPack, an online pharmacy founded in 2013, focused on treating chronic conditions. It offered pre-packaged and sorted treatment regimens for its patients to ensure that they received the correct treatment in a timely way. PillPack was similar to Blue Apron, a service that delivers pre-measured ingredients for home-cooked meals, but instead of providing pre-planned meals, it provided pre-organized treatments.

In 2018, Amazon purchased PillPack for $753 million, integrating its service into Amazon’s substantial ecosystem. In 2020, Amazon itself entered the pharmacy space by launching Amazon Pharmacy, allowing customers to obtain their prescription drugs through the Amazon ecosystem. It simultaneously added a prescription drug benefit to its Prime service. Prime members receive a discount card, like those used by GoodRx and other PBMs, allowing them to obtain generics for up to 80 percent off list price at more than 60,000 pharmacies nationwide, including Amazon’s. In early 2023, Amazon introduced another prescription drug offering for its customers — RxPass. Essentially, RxPass operates like the arrangement where Netflix used to deliver DVD movies by mail. For a monthly $5 subscription fee, participants have access to generic drugs, covering 50 common conditions, at no additional charge.

Capsule is a full-service digital pharmacy similar to Amazon Pharmacy. Founded in 2015, it is known for the promise of free, same-day delivery of medication in the cities it serves. Like traditional brick-and-mortar pharmacies, Capsule accepts insurance as a form of payment. Currently, Capsule serves only 22 US metropolitan areas, so its service is not yet available to Americans nationwide. For those who use their service, it offers telehealth chats with pharmacists, should the patient have any questions.

Another competitor in this area is the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company (MCCPDC). The MCCPDC is an online-only pharmacy specializing in generics that sells drugs at a fixed markup of 15 percent over the cost it pays for the drugs, generally from wholesalers.

It eschews PBMs and insurance. It also produces some generics in-house. Honeybee Health and DiRx are companies that operate similarly to MCCPDC.

Another service like MCCPDC is ScriptCo. However, instead of a fixed 15 percent markup, it charges a monthly subscription fee of $10. Subscribers then have the option of purchasing their prescribed drugs for the wholesale cost with no markup at all. Like some of the other options, ScriptCo is entirely online and does not accept insurance.

Blink Health is another prominent innovator in the pharmaceutical delivery market. Blink operates BlinkRx, which manages the complex network of brand-name pharmaceutical products. When a consumer wants to purchase a brand-name drug, they can use BlinkRx to quickly determine the lowest out-of-pocket cost. BlinkRx uses internal data to run through the customer’s insurance, copays, deductibles, any manufacturer discounts available, and prior authorization requirements. It then connects with a pharmacy to provide at-home delivery. The goal is to streamline the process for consumers and minimize their costs.

What the online pharmacies have in common is that they continue to add options for consumers. They make the shopping experience better in one or more ways and increase overall welfare. Currently, online pharmacy revenues represent $5.7 billion of the $300 billion retail pharmacy sector. Analysts expect that to continue to grow.

Combined pharmacy and telehealth offerings

One of the innovations in the pharmaceutical delivery market is in services that combine telehealth with pharmacy services. These offer convenient, all-electronic services where patients can be diagnosed, prescribed treatment, and supplied treatment, all online. Currently, these services focus on a small number of diagnoses and treatments, but this avenue is expected to grow.

Currently, the two largest platforms that offer these services are Ro and Hims & Hers. Ro treats weight issues, hair loss, and acne, among other health concerns. It is the exclusive direct-to-consumer provider of Plenity, a weight management aid. Generally, Ro prescribes generics, but it does offer some branded drugs. Ro does not accept insurance, but conducts business directly with consumers.

Hims & Hers offers several of the same treatments as Ro but also handles contraception and drugs for chronic conditions such as high cholesterol and high blood pressure. Hims & Hers favors a subscription model for its prescriptions. In 2024, Hims & Hers announced the construction of a facility to be used for compounding drugs and manufacturing peptides, which are used in GLP-1 weight-loss drugs.

Both Ro and Hims & Hers employ licensed physicians for their telehealth services and licensed pharmacists for the pharmacy and aim to expand coverage nationwide. Treatments covered by Ro and Hims & Hers have often focused on options that traditional insurance does not cover. Their existence demonstrates the market’s flexibility and dynamism, as they developed to fill in a gap that existed.

Likewise, should other gaps exist or arise, existing services can evolve or new services can be created to fill those gaps. In addition to Ro and Hims & Hers, there are similar providers that offer specialized care, such as Nurx and Lemonaid. Other services with this model offer more general care, such as Teladoc Health and Amwell.

Growth in mail-order drugs

Over the past 50 years, drugs that are considered “maintenance drugs” have become a larger component of the drug industry. Treatments for high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and soon probably GLP-1s need to be taken regularly for an extended period.

Because of the regularity, consumers have found it more convenient and more economical to procure large quantities along with less frequent refills. This saves the time of going to the doctor’s office, waiting, getting a check-up, obtaining a prescription, taking it to the pharmacy, and getting a refill.

Because these transactions are done by mail, suppliers can operate and dispense these drugs out of larger warehouses, which reduces inventory and real estate costs. These savings have been obvious for retailers such as Amazon and Walmart. They maintain inventories at geographically dispersed, large warehouses so that consumers can receive their goods more quickly and at lower prices.

Another opportunity for cost-saving with mail-order delivery systems is automation. Sophisticated robots are a fixed cost for companies, and smaller operations may not have the scale necessary to cover that cost. Such investments lower overall costs, which eventually funnel down to consumers.

Mail-order pharmacies can also lead to fewer prescription errors. According to one study, prescription errors are the most frequent and avoidable sources of harm in the health care sector. It is true that when processes are more dispersed, mistakes will be less consequential, as they will be isolated to just one pharmacy that serves a small number of people. However, when a process is centralized, companies can hire higher-quality workers, including workers who focus entirely on reducing errors. Further, the ability to invest in automation tends to reduce mistakes. UnitedHealth Group estimated that home delivery saved US consumers $600 million per year before accounting for improvements in adherence.

Mail-order pharmacy sales made up 40 percent of total retail prescription revenues in 2025, up from 37 percent in 2017. The major providers of mail-order pharmaceuticals are PBMs. In addition to these online-only options, pharmacy chains such as CVS and Walgreens also offer mail delivery services as extensions of their retail operations.

Understanding TrumpRx

One of the newest entrants into the pharmaceutical drug market is TrumpRx. Announced in September, TrumpRx is a direct-to-consumer portal that will be operated by the federal government. Several companies have already announced their participation, including Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Eli Lilly. Currently, the expectation is that TrumpRx will allow drug manufacturers to sell their drugs directly to consumers, bypassing pharmacies and PBMs entirely.

TrumpRx is expected to cover a multitude of drugs, including even cutting-edge GLP-1s. The drug manufacturers’ commitments have frequently offered prices below list price, and close to prices that prevail for Medicaid and Medicare patients. For some drugs, the prices are set at the “most-favored-nation” prices, or the lowest prices that manufacturers sell drugs in the price-regulated international markets.

Pharmaceutical companies stand to benefit from this arrangement for several reasons. First, they will bypass the other stages of the supply process, meaning they can eliminate double or triple marginalization in the drug supply chain (discussed in detail below). Second, direct purchase does provide the companies with additional consumer data that they may be able to use effectively to build customer relationships. Third, while these companies are offering a lower price than list, which is likely lower than they are receiving from their other distributors, this price is still often above the out-of-pocket cost that insured patients face, meaning the majority of the purchasers will continue to obtain drugs through their insurance, their primary supply vector.

TrumpRx benefits consumers by offering them another source for the purchase of drugs at a lower price. This will add competition to the market, which tends to benefit consumers, not just on price, but in convenience and access as well. Details of TrumpRx remain subject to implementation and may change as federal agencies finalize program operations.

More options benefit consumers

Many of these online services are upfront about not taking insurance, which may seem to limit their reach. Yet many people with insurance have found it advantageous to utilize these services. The growing customer base these services cater to illustrates the benefits they provide to consumers.

Taken together, these options demonstrate the rapidly evolving marketplace for drugs that consumers are facing, adding enormous competition to the market. With online availability, price comparisons become much easier, reducing search frictions and increasing pressure on prices to move lower. Competition does not just benefit consumers through lower prices, but also through improving the quality of, in this case, the procurement of pharmaceuticals, making the process quicker and more convenient, with fewer mistakes.

None of these distribution channels is a panacea for every challenge in pharmaceutical distribution. Still, through competition and diverse choices, consumers can pick and choose which option serves them best in different situations, leading to immense overall improvement.

Brick-and-mortar pharmacies show strength

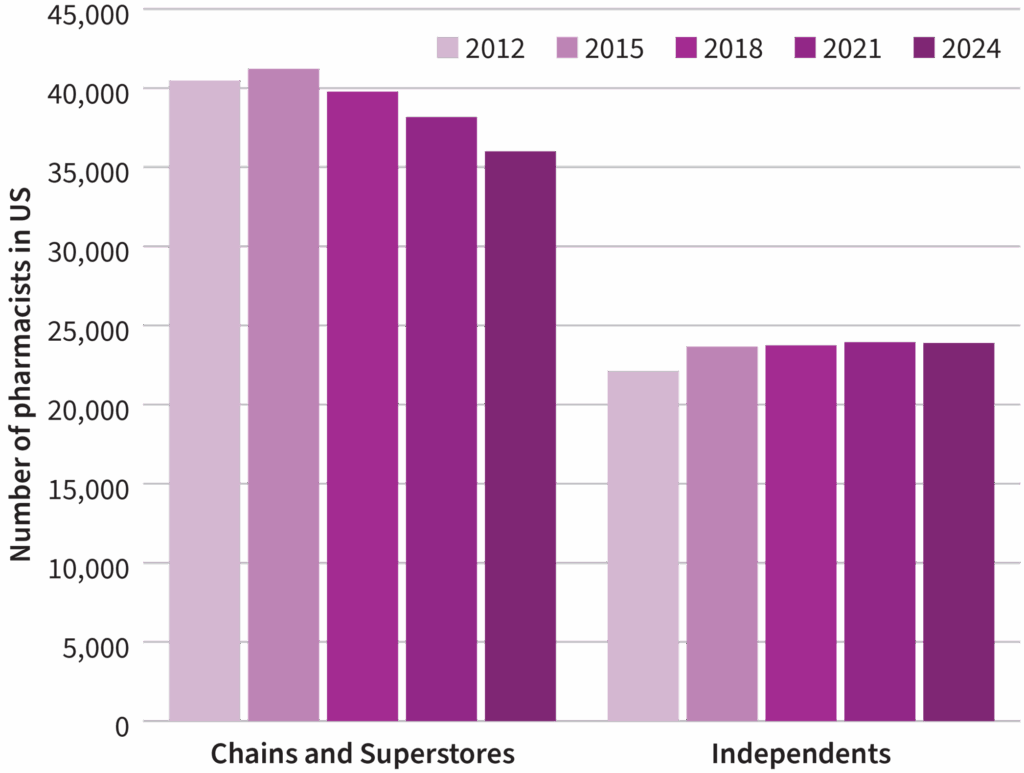

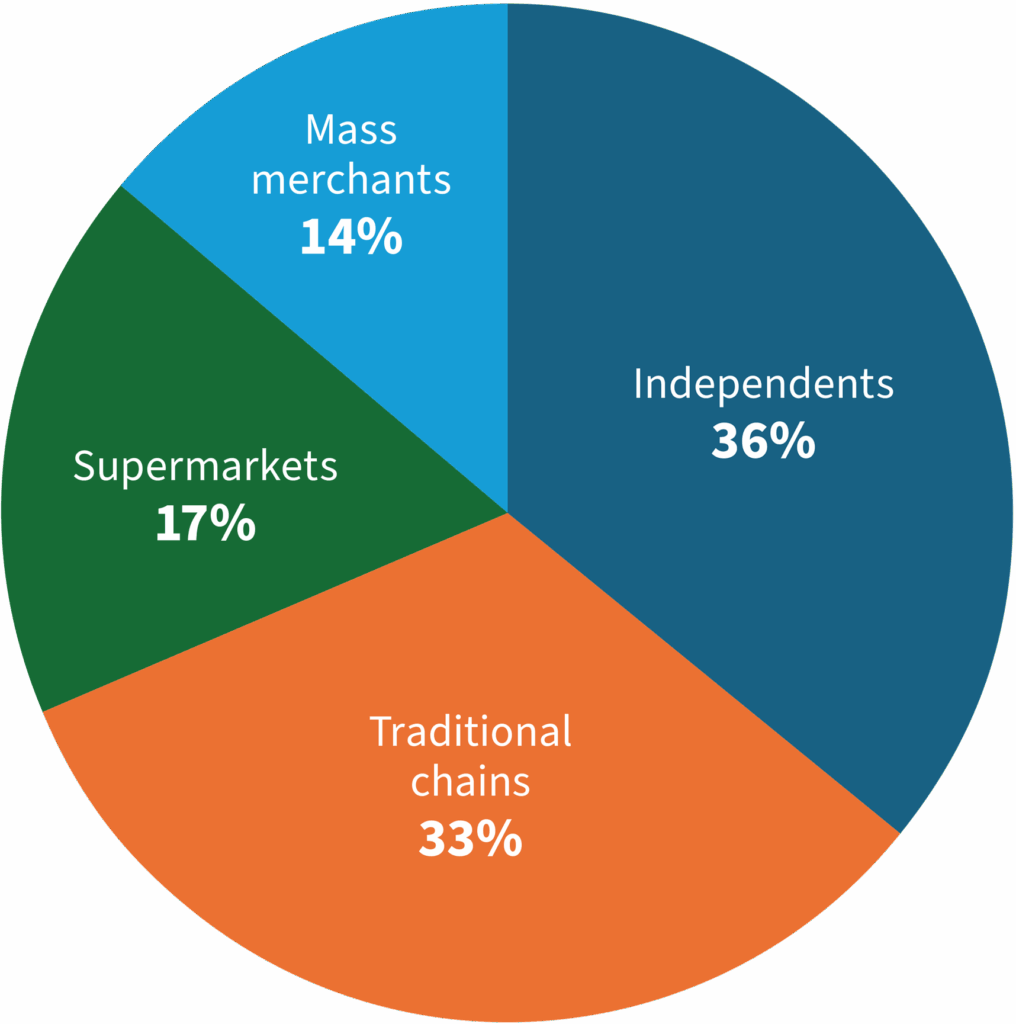

Even while the pharmacy industry is experiencing dynamism and growth, brick-and-mortar pharmacies, particularly independent pharmacies, have been keeping up. According to McKinsey analysts, the consolidation phase for large retailers has ended, and the shrinkage of independent pharmacies stopped 25 years ago.

The graphic below shows the number of pharmacies from 2012 to 2024 for two categories of pharmacies. On the left are chains (CVS, Walgreens, etc.) and superstores (Walmart, etc.). It demonstrates the point above in that the number of chains and superstores has fallen by approximately 5,000 over this time span, while the number of independent pharmacies has risen slightly.

In fact, there are more independent pharmacies than retail chains and regional pharmacies. Independent pharmacies make up approximately 35-36 percent of all retail pharmacies.

Prescriptions at independents have been going up. According to the HDA Research Foundation, while prescriptions rose 2.4 percent across the whole country, they rose slightly faster at independent pharmacies. According to the NCPA, independent pharmacies are running gross profit margins of close to 20 percent. This is very close to the gross profit margins that CVS and Walgreens enjoy.

Vertical integration in pharmacies

Recently, policymakers have begun to worry about the pharmacy industry due to affiliations and relationships across the supply chain. Several states have considered legislation to prevent pharmacy benefit managers from owning pharmacies, and Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Josh Hawley (R-MO) put forward legislation at the federal level. Some of these alliances have led legislators and competitors to express concern over the potential for abusive practices that reduce competition, harming competitors and consumers alike.

A common theme in these arguments is the allegation that vertically integrated firms may harm an industry. Vertically integrated firms are firms that operate in two separate markets along the supply chain, such as an oil company drilling and refining oil, then selling gasoline to consumers. The research on and practical experience of vertically integrated firms generally show that such firms are good for consumers and any risks are low. They offer major benefits, both in prices and options for consumers, and any concerns regarding the firms manipulating the market to benefit themselves at the expense of consumers can be addressed through transparency and without full-scale regulatory prescription.

Benefits of vertical integration

Like many other business components, vertical integration can be seen as a push and pull of costs and benefits. This question was discussed seminally in a 1950 paper by Duke University economist Joseph Spengler. The benefits to the firm are an increased level of control and predictability over elements of the business. A retailer must make arrangements with the manufacturers or wholesalers of goods they resell to ensure a steady supply. Because the retailer has no control over these firms, it can often face unpredictable disruptions. These disruptions could hurt the retailer’s business, and firms may conclude that exerting control over the the production of goods they are selling can prevent or smooth out those disruptions and minimize interruptions for customers, which, in turn, boosts profitability.

Reduced transaction costs: Of course, supply disruptions can be addressed through other means as well. For example, the company may choose to stipulate precise contractual terms with a supplier instead. Firms constantly face the dilemma of balancing costs and benefits to maximize their long-term success. In some cases, contracts are the best path. In other cases, vertical integration is a superior solution.

Consider, too, that the supply of inputs is only one example of vertical integration. Vertical integration also includes smaller aspects of business, such as hiring, HR, labor, IT, and building ownership. Theoretically, any of these can be outsourced, but many firms find it beneficial to handle these aspects themselves, for similar reasons to why they vertically integrate across the product supply chain: to practice more control, to ensure the services meet their quality standards, and even to tailor these services to themselves. For instance, a company may have particular needs when it comes to real estate that will not be met by leasing property. It is therefore in the company’s interest to own and possibly design its own buildings.

Vertical integration also allows companies to take advantage of economies of scale. Instead of two companies with two of every department, one larger company can economize on professionals and infrastructure.

The decision on whether to handle each of the individual elements of a firm’s operations can be expressed as a problem of transaction costs. In the contract arrangement, the transaction costs are those of designing and overseeing the terms and contending with unforeseen problems. When the process is completely internalized, the transaction costs still exist but are of a different nature. They revolve around hiring quality employees and managing them to ensure needs are met. Ronald Coase described much of this in his 1937 article “The Nature of the Firm.” When these transaction costs become too high to maintain, firms seek alternative, internal solutions.

Every firm faces these decisions and continues to modify what is done internally versus externally over time, as situations change. A company may rent an office when it is small. As it gets larger, it finds that business would operate more efficiently by designing, building, owning, and managing its own real estate. Or maybe the efficiency never changed, but the cost was simply too high when the company was small.

For pharmacies, these benefits can manifest as offering more drugs, including specialty medications, or by becoming a compounding pharmacy. Perhaps it creates its own prescription management software or a special type of bottle. These are relatively minor examples of vertical integration, but a large enough pharmacy could even consider manufacturing its own drugs or performing some or all of the functions of a pharmacy benefit manager, such as mailing out prescriptions or managing the needs for beneficiaries of an entire insurance company. Doing so could result in improved, economical, and convenient offerings of medicines for the customer.

Increased customer information: The advantages of vertical integration extend beyond ensuring a steady supply, and can also encompass product design. When Amazon, for example, produces its own goods for consumers, it has additional control over the quality of those goods to ensure that they meet customer needs. Further, if Amazon’s customers differ from the average consumer, Amazon can modify the goods to meet those customer needs. As a vertically integrated firm, Amazon has a level of information on the preferences of its customers that an external manufacturer would not. It can use that information to design products directly for its customers. This is a competitive advantage for Amazon, and also a benefit to consumers.

Some pharmacies have begun to branch out vertically by manufacturing their own drugs. This demonstrates many of the benefits of vertical integration. As these pharmacies’ distribution markets grow, they have found it advantageous, lower-cost, and more sustainable to manufacture certain drugs themselves. By doing so, they can ensure a steady supply and offer better products for their consumers.

For pharmacies that are integrated with pharmacy benefit managers, on the other hand, the increased information that the combined firm has could be highly beneficial to consumers. It would create new opportunities for insurers to practice care coordination by monitoring medication adherence. Elevance Health developed a program in which it works with community pharmacies to do this for Medicaid beneficiaries. It could also provide PBMs information that would allow them to improve the range of pharmaceutical products they cover, given supply issues and changes in cost. Additionally, having a full spectrum of data on patients and the scale to invest in technologies that coordinate it can reduce the risks of drug interactions, duplications, or errors.

Double marginalization nixed: Another benefit of managing more aspects of the business in-house is the elimination of double marginalization. When a company hires another firm to perform a task, the other firm is operating in its own industry and presumably making a profit. The company that is hiring the contractor is also trying to make a profit. So effectively, the price that the customer sees includes both of these firms’ profits. This is what is referred to as double marginalization.

A single, vertically integrated firm eliminates this double marginalization issue because it is a single firm. In practice, the overall price the customer pays will fall because of cost savings and lower overall profits.

Risks of vertical integration

In contrast to vertical integration’s benefits, critics point out that it can come with some risk to consumers. Primarily, the risks involve preferencing a firm’s own products using all the information and tools at its disposal, and reducing horizontal competition in markets that the firm cuts through vertically. Steering and access to competitor information are two oft-cited concerns.

Steering: One of the most common fears cited by those who oppose vertical integration in the pharmaceutical sector is that of preferencing affiliated outlets, which would harm competition and access for consumers. In the case of health care, this would manifest as insurance companies steering patients toward hospitals they own. Similarly, if PBMs were to own pharmacies, they might steer customers toward their own pharmacies despite the existence of options customers might prefer. They could accomplish this in several ways, such as by offering lower copays to customers who stay within the organization or by excluding outside pharmacies, or, theoretically, by adding additional fees for going elsewhere.

There is little evidence to suggest that this is happening in the pharmaceutical industry. The FTC’s report on PBMs included a section on this issue, yet the case made by the FTC was overwhelmingly based on theoretical harms and anecdotal data, and very little analysis or research showing that this is a widespread issue based on our review of the report’s cited examples and methodological discussion. Nor did the report investigate any evidence that might contradict it, such as systematically comparing the networks or copays of PBMs with vertically integrated pharmacies to those that have none. It did mention that PBMs and PBM-affiliated groups disagreed with the agency’s contentions, but the report included no suggestion that the authors made any effort to disprove or challenge their original thesis.

In addition to the FTC, the House Committee on Oversight and Accountability put out a report on PBMs in 2024. The Oversight Committee’s report contained many of the same criticisms included in the FTC’s report. Also like the FTC’s report, the Oversight Committee was heavily reliant on anecdotes and selective statistics. For example, one section of the report says:

In reviewing standard formularies for 2020, 2021, and 2022, from the three largest PBMs, the Committee found 300 examples, which can be found in the Appendix to the report, of the three largest PBMs preferring medications that cost at least $500 per claim more than the medication they excluded on their formulary [the list of drugs covered by the insurer]. While some of these decisions likely have valid clinical reasons, the sheer quantity and dramatic increase in costs highlight the priority of PBMs.

Missing from this criticism is what percentage of medications the Committee’s 300 examples represent. If the Committee found 300 examples out of 30,000, that is an entirely different situation than 300 out of 500. In the former case, the “valid clinical reasons” or even economic reasons would make the situation, which is sold as a huge problem, more accurately a minor statistical aberration. The Appendix referred to in the text shows only the 300 examples that make up the Committee’s claim. Without context, it is impossible to determine whether these examples are representative of some kind of anti-competitive abuse, reasonable given the circumstances, or just statistical aberrations.

A cursory review of the data suggests it is the latter. According to the Appendix, 65 of the 300 examples the Committee cites are from Express Scripts. According to Express Scripts, its formulary includes 600 brand-name drugs and 99 percent of all generics, which amounts to 32,280 drugs. Consequently, the House Oversight Committee’s examples may represent 0.2 percent of Express Scripts’ formulary.

Secondly, the number of PBM-owned retail pharmacies is too small to seriously endanger competitors, implying that the major concern from legislators is the mail-order element. The best way to address this potential problem is not wholesale proscription of vertical integration but to target the issue using network adequacy requirements, which we will address shortly.

Competitive advantage: Another often-discussed risk of vertically integrated firms is that the integrated firm will have information about rivals due to its presence at multiple levels of the process. For example, Amazon functions as both a retailer and a manufacturer of items sold on its platform. Amazon competes in manufacturing charging cords with other manufacturers using its platform, such as Monoprice and Anker. As a retailer, Amazon can see how demand is affected by prices, and can quickly, perhaps instantaneously, undercut any price change by its competitors. The access to data on its competitors certainly gives it an advantage.

In the PBM/pharmacy context, the argument would be that a pharmacy integrated with a PBM may have access to beneficial data about other PBMs’ prices for drugs. However, some of this information is available publicly already. GoodRx operates by showing the lowest PBM-negotiated price for a drug at every pharmacy, which already gives PBMs information about the lowest prices their competitors are charging. Pharmacies have sued PBMs alleging they are coordinating their prices through GoodRx. If a pharmacy were owned by a PBM, other PBMs would likely consider that when setting prices at that pharmacy and negotiating, mitigating any potential harm.

Vertical integration produces a net benefit

Research has found that vertical integration is beneficial in the majority of circumstances. Studies focusing on television, airlines, telecom, concrete, and film all reach the same conclusion. Economists Francine Lafontaine and Margaret Slade conducted a literature review of the evidence and found “under most circumstances, profit-maximizing vertical integration and merger decisions are efficient, not just from the firms’ but also from the consumers’ points of view.” They concluded, “restrictions on vertical integration that are imposed, often by local authorities, on owners of retail networks are usually detrimental to consumers.”

Consider, too, that the economy has several examples of vertically integrated firms, such as PBMs and pharmacies competing with other, non-integrated firms. The vertically integrated firm, while it has certain advantages, usually ends up benefiting consumers without foreclosing competition. A 2023 study found that a pharmacy subscription program, which featured reduced prices for generic drugs, was associated with more refills and lower out-of-pocket costs. A 2016 review of research concluded that patients who used mail-order pharmacies, which are often operated by PBMs, showed higher adherence to their medication.

In a 2023 report to Congress, MedPAC, the government agency responsible for analyzing the performance of Medicare, found that premiums for Part D plans, which focus on pharmaceutical access for Medicare beneficiaries, fell about 20 percent between 2018 and 2022. Most Part D plans are vertically integrated, meaning the insurance companies that offer these plans use their own PBMs to manage the pharmaceutical component. In a period of rising drug prices, lower prices for consumers strongly suggest that the benefits of vertical integration outweigh the costs.

Vertically integrated firms offer a variety of benefits to firms and consumers. Research has shown that in the preponderance of cases, the efficiencies are passed down to consumers in the form of lower prices or better products and services. This fact should weigh heavily when considering whether additional oversight is needed in the pharmacy industry.

Prohibition will harm consumers

We have seen in detail how innovative and dynamic the pharmaceutical distribution market has become in the past 20 years. American consumers currently have unprecedented options to obtain pharmaceuticals, and that list of options continues to grow. Options allow them to choose how to balance the convenience of buying these products against the prices offered. The more options consumers have, the better they can tailor decisions to their own preferences. The consumer is not locked into one of these options and may choose different ways to obtain pharmaceuticals based on current life circumstances and the treatment itself.

For example, perhaps a consumer has a severe infection and wants the prescribed treatment immediately. In this case, they might travel or have someone travel to the pharmacy on their behalf to pick it up. This could occur at the same moment when they need to renew a prescription for high blood pressure, for which they can choose to renew the mail order or let Amazon RxPass handle it, confident that there will be a continuous supply.

Legislation that forecloses any of these options will impose more harm than benefit. There is little evidence to suggest that PBM-owned pharmacies or mail-order pharmacies are engaging in the worst theoretical practices that vertically integrated firms might undertake. There is plentiful evidence that consumers benefit from having these pharmacies as an option.

Should a bill preclude PBMs from owning brick-and-mortar or mail-order pharmacies, consumers will suffer. A bill doing this was passed in Arkansas earlier this year, and CVS has already threatened to close its stores in the state should the legislation go into effect. This would deprive Arkansas residents of a convenient, 24-hour pharmacy available at any time, and often of prices similar to or better than other pharmacies.

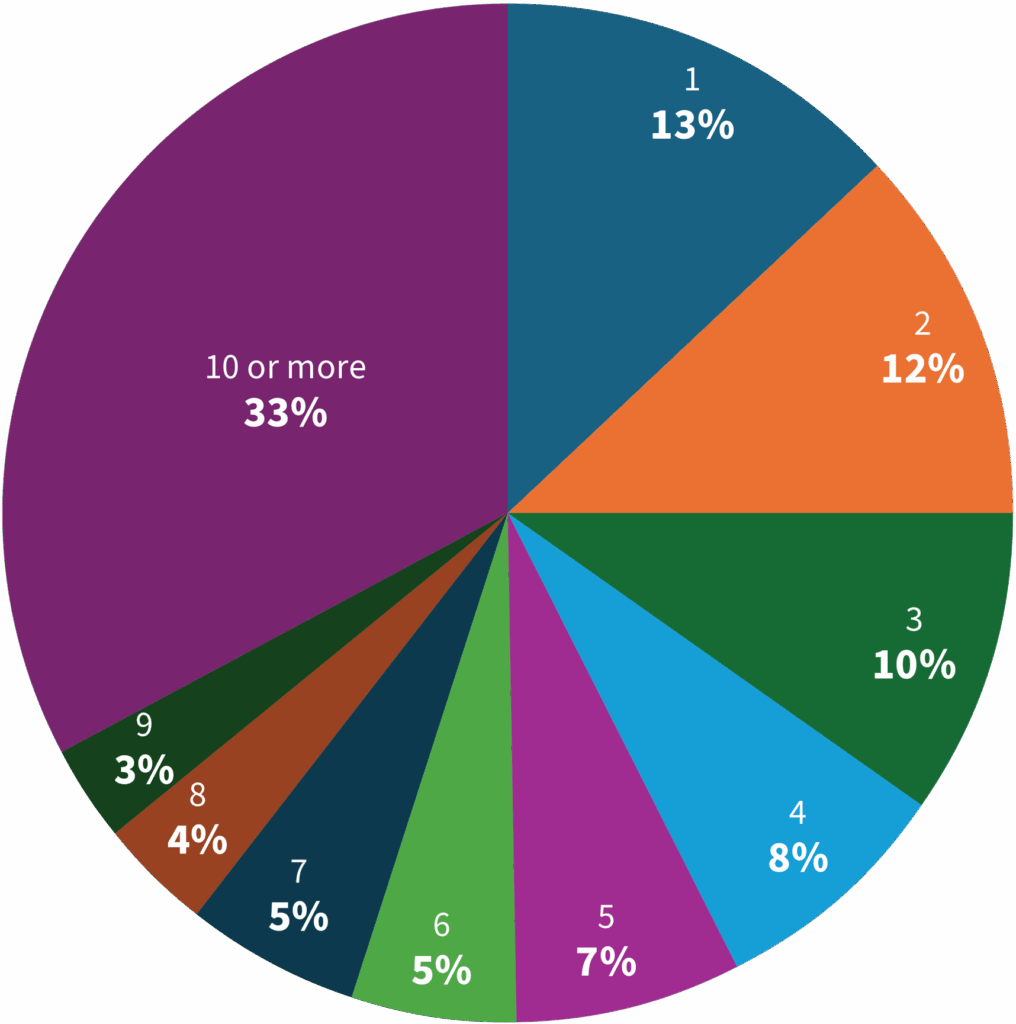

Removing mail-order pharmacies from the market would also lead to decreased medicine adherence, shorter prescriptions, higher prices, and more effort from everyone who currently uses them. These would include people suffering from chronic conditions, who might be home-bound, or have a disability that makes it more difficult for them to travel to the doctor’s office and the pharmacy, which may be even farther away if their preferred pharmacy was vertically integrated and closed because of the legislation.

Prohibiting PBM-owned pharmacies and mail-order pharmacies would certainly reduce consumer choices and a significant avenue by which PBMs lower costs and streamline prescription drug delivery for their customers. This would reduce overall consumer welfare, as 13 percent of counties with at least one pharmacy have only one pharmacy. There are 149 counties across 33 states with no retail pharmacies at all. These consumers are reliant on internet pharmacies, mail-order, or traveling long distances.

Availability of pharmacies by county

There are seven counties in the United States where the only pharmacy is a PBM-owned pharmacy. Of the approximately 1,000 counties with 1-3 pharmacies, nearly 100 of them have at least one pharmacy owned by a PBM. These would be the pharmacies and residents most likely to lose out if legislation banned PBM-owned pharmacies.

Banning PBM-owned pharmacies would also reduce competitive pressures on the other pharmacies that are vying for customers. Reduced competition will affect prices, meaning higher out-of-pocket costs and higher premiums. To understand why, one needs to understand the role PBMs play in the pharmaceutical sector. PBMs are much like insurance companies. They operate in a similar way, building networks and negotiating prices. Often, they do these things at the same time and use one side of the equation to backstop the other. Instead of building networks of hospitals the way insurers do, PBMs build networks of pharmacies. As part of their price negotiations, PBMs negotiate with pharmacies on the price for the drug and also with the drug manufacturers for rebates on brand-name drugs. On both sides, a competitive PBM would reduce costs for consumers, at the counter through copays and through premiums paid to their insurers.

The existence and the pressures of competition are very likely major factors driving legislation to ban PBM-owned pharmacies. It is a common phenomenon in government regulation that companies seek government involvement to clear out their largest competitors. Certificate of Need Laws are often used by existing health care providers to block the entry of competitors. Hotels in New York City successfully got a law passed that effectively banned Airbnb.

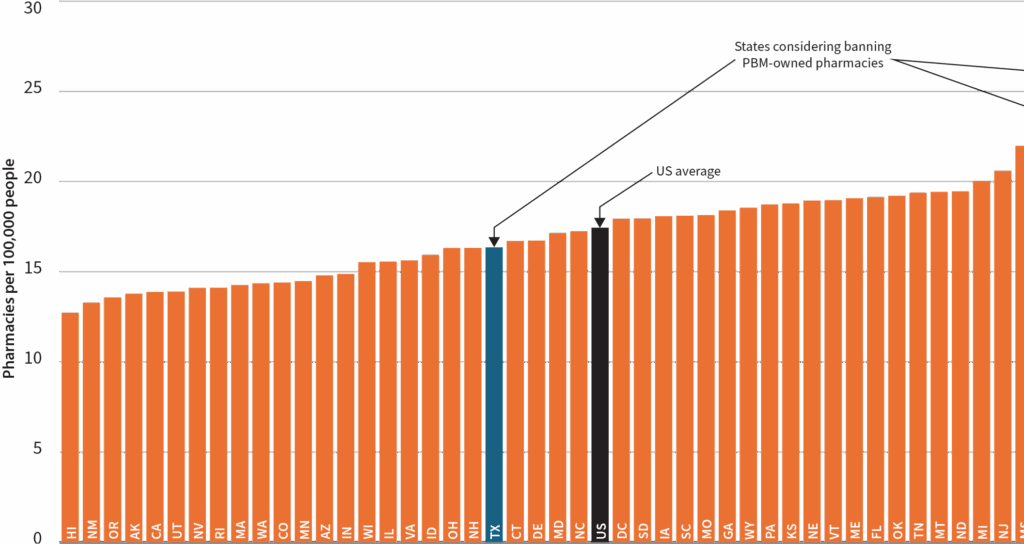

States considering banning PBM-owned pharmacies are near or above the national average for pharmacy access. The graph above shows each state’s number of pharmacies per 100,000 people. The three states considering banning PBM-owned pharmacies are New York (second highest), Arkansas (fifth highest), and Texas (slightly below the US average). Pharmacy access does not seem to be the driving motivator here.

Competition does not just benefit consumers through lower prices, either. Competition between firms encourages innovative delivery mechanisms. The explosion of options demonstrates how competition in the pharmacy sector has benefited consumers and is continuing to evolve. Slowing that down may benefit existing participants but will discourage further innovation, to the detriment of consumers.

All the benefits with little of the cost

Concerns about the potential harms of vertical integration can be addressed using current laws or less intrusive network adequacy laws. There already exists an extensive set of laws and court decisions regarding abuses by vertically integrated firms. These apply to PBM-owned pharmacies and afford a level of protection for consumers and competitors. They include scrutiny of vertical foreclosure, prohibitions on tying and bundling, restrictions on exclusive dealing, refusals to deal, and price discrimination.

For PBMs in particular, network adequacy laws are a suite of laws applicable to the pharmacy market, PBMs, and PBM-owned pharmacies. Network adequacy laws fall into three main categories. Some laws are designed to ensure that patients have consistent and broad access to multiple choices for pharmacies, and often, mail-order options are explicitly excluded from the calculation.

Certain states, including Florida, Mississippi, and New Hampshire, require PBM networks to include pharmacies within a certain distance of their customers. Both Arkansas and Delaware require PBMs to submit reports on their pharmacy networks to regulators so that they may be reviewed for accessibility. Florida has stipulated that PBM pharmacy networks must include non-affiliated pharmacies.

Notably, self-insured employer plans are typically not subject to many of these laws. Because they are covered by federal laws, state laws do not apply to them in most cases. However, PBMs that work with self-insured employers often meet the objectives voluntarily. For example, PBMs that work with employers design their nationwide networks such that they meet or exceed the state geographical requirements.

In addition to network adequacy, as of 2023, more than 30 states had enacted an “Any Willing Provider” law. These laws require insurance companies to include any provider, particularly pharmacies, that agrees to the terms of a plan. Such laws aim to prevent insurance companies or PBMs from using their network design to exclude competitors and favor their affiliated pharmacies. In Oklahoma, the law prohibits insurers and PBMs from compelling beneficiaries to use pharmacies they own.

These laws typically apply to non-employer-based commercial insurance and Medicaid beneficiaries, not to employer-based insurance. Medicare Part D, which covers prescription benefits, has its own network adequacy laws that largely produce the same results as these state laws.

Across these payers and systems, consumers and competitors are already benefiting from strong protections, whether from the competitive pressures of a vibrant industry or from the regulations and oversight that already exist. Adding a new barrier to entry will only weaken the competitive forces operating effectively, which will harm consumers.

Conclusion

As the country ages and the pharmaceutical industry matures, the distribution of medicines to the people who need them evolves along with them. Legislators across the country are considering new laws that will interfere with market forces and direct the market towards an outcome that will be bad for consumers, under a mistaken understanding of how the industry operates.

Pharmacy benefit managers receive substantial scrutiny and criticism largely because they are removed from the customer, so very few see their prices or know the details of their operations, and because, as a third-party payer, they have to make the decisions on how much to pay. Because of the indirect nature of payments in health care, both customers and providers want them to spend more. Pharmacies in particular are resistant to the objective of PBMs — to keep drug prices down — because they are the ones being paid.

Legislation that bans a specific business arrangement, namely a single application of vertical integration, will reduce competition across pharmacies and remove an opportunity for more efficient delivery of pharmaceutical products to customers. When many people are worried about pharmacy deserts, restricting certain forms of pharmacies is counterproductive, and in the areas that are considering these laws, these pharmacies are not about to drive independent pharmacies out of business. Policymakers should tread extremely lightly to avoid harming consumers with misguided and harmful regulations and prohibitions on a market they are unqualified to manage.