Empire State of Mind

Curing New York State’s Environmental Permitting Hangover

Executive Summary

New York State’s environmental permitting procedures represent a mixed bag. On the one hand, the Uniform Procedures Act (UPA), signed into law in 1977, has provided a stable framework for the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation processes, standardizing procedures across a wide range of programs. By establishing consistent requirements and timeframes for certain actions at this one state agency, the UPA has created a more predictable and efficient system for both permit applicants and regulators.

On the other hand, New York’s State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQR), which requires environmental impact assessments for many government actions at the state and local level, is a much broader and more sweeping law that often leads to protracted, open-ended permit reviews that create significant uncertainty for applicants. Moreover, the permitting process has grown more burdensome over time, as additional layers of review have been added. For example, factors such climate risk and environmental justice have increased in priority in recent years. Further changes to the process have sought to fast-track permitting for renewable energy projects. This provides some benefits but also creates an increasingly bifurcated process where renewable projects are singled out for special treatment.

Potential reforms in New York could include simplifying or even repealing SEQR, reducing redundancies with other environmental laws, and carefully limiting public engagement so it doesn’t become a roadblock to productive projects. The UPA could also be expanded to include permits outside the state Department of Environmental Conservation.

The Uniform Procedures Act

In 1977, during his annual message to the legislature, New York Governor Hugh Carey called upon the state legislature to enact measures to streamline the state’s environmental permitting processes. Carey, a Democrat, sought to balance the twin goals of environmental conservation and economic growth by eliminating costly delays and unnecessary obstacles in the regulatory system. In response, the New York state legislature passed the Uniform Procedures Act (UPA).

The express legislative intent behind the UPA centered on ensuring “fair, expeditious and thorough administrative review of regulatory permits,” eliminating inefficiencies and redundancies, and encouraging public participation in the permitting process. When Governor Carey signed the UPA into law, he noted that while environmental regulations serve important objectives, they also increase costs for businesses, and he believed the UPA would prevent “costly delays” and “frivolous concerns” from hindering the intended purpose of environmental regulations. In signing the UPA, Carey also expressed hope that the law would serve as a model for other states to follow in reforming their own regulatory procedures.

New York’s UPA established a framework for the state Department of Environmental Conservation’s (DEC) processing of permit applications for major regulatory programs. The UPA’s key features include the following:

- Applicability to Environmental Permits: The UPA applies to permits for activities regulated by the DEC, including protection of waters, wetlands, air pollution control, waste management, mining, and several other programs.

- Uniform Procedures and Timeframes: The UPA requires the DEC to follow consistent procedures and timeframes for reviewing permit applications. This includes deadlines for notifying applicants whether applications are complete and for making final decisions on complete applications.

- Distinction between Minor and Major Projects: The UPA implementing regulations categorize activities as either minor or major projects. Minor projects are those deemed by their nature and location as unlikely to have significant environmental impacts. Minor projects are not subject to the same public notice and comment procedures as major projects and they also have shorter decision timeframes.

- Public Notice and Comment: The UPA requires a public notice and comment process for complete applications for major projects. This provides an opportunity for public input on proposed projects before final decisions are rendered.

- Procedures for Hearings: The UPA and implementing regulations establish procedures for determining whether public hearings will be held on permit applications and the timeframes for holding such hearings.

- Completeness Determinations and Application Timelines: The UPA specifies the timeframes for the DEC to notify applicants whether applications are complete, noting that the department has fifteen calendar days after the receipt of a permit application to mail written notice to the applicant as to whether or not their application is complete.

- Permit Decision Timeframes: Once applications are complete, the UPA mandates timeframes for DEC to make final permit decisions—45 days for minor projects, 90 days for major projects if no hearing is held, and 60 days after the close of hearing records.

Benefits and Costs of the UPA’s Core Features

The UPA’s core features offer several benefits for the environmental permitting process. First and foremost, the UPA ensures consistent procedures are followed for projects with potentially significant environmental impacts that fall under the DEC’s jurisdiction. The uniform nature of the UPA’s procedures and timeframes across a wide range of different permit classes establishes a level of predictability and certainty for applicants, helping to reduce regulatory uncertainty.

The distinction between minor and major projects is another beneficial feature, allowing the DEC to expedite the processing of minor projects that are unlikely to have significant environmental impacts. Minor projects should have decisions within 45 days after the day the application is complete. This approach enables the agency to focus its resources and public input processes on the major projects that warrant greater scrutiny. Even for major projects, however, the public input process has standardized limits in terms of duration, so community input doesn’t become a source of excessive delay and obstruction.

Relatedly, the UPA’s procedures for hearings serve to ensure that projects with significant impacts or high levels of public interest have a forum for more extensive public participation. By establishing clear triggers and timeframes for holding hearings, the UPA helps to limit public input from becoming excessive or becoming a tool to block projects. Similarly, the defined criteria and timeframes for completeness determinations set clear expectations for when applications are sufficient for DEC review. This benefits both applicants and the agency by avoiding wasted time and resources on incomplete submissions. Once applications are deemed complete, the UPA’s permit decision timeframes provide applicants with a promise of a timely decision, helping to limit prolonged regulatory uncertainty. The UPA also allows DEC to delegate certain civil and criminal enforcement powers to other state and local agencies, and also requires, at the applicant’s request, that DEC coordinate with other regulatory bodies with jurisdiction.

One drawback of the UPA is that while the statute itself is fairly short, the implementing regulations are lengthy, at about 70 pages. This highlights how even simple, relatively short and straightforward statutes can spawn regulations that become unwieldy. Additionally, while the UPA’s permit decision deadlines help to ensure timely action, the DEC still possesses a fair amount of discretion over when an application is deemed complete and, by extension, when the official clock starts ticking. Finally, the UPA’s scope is limited, as it only affects certain proceedings before the DEC, while permitting decisions at other agencies fall outside the bounds of the law.

New York’s SEQR Law

While the UPA in New York constitutes a potential model other states might wish to emulate, the permitting process in New York is still far from ideal. Controversies range from fights over preemption of local zoning codes for renewable energy projects to how to best consider impacts on disadvantaged communities as part of New York’s aggressive “zero emission” goals for its electricity sector. One of the largest sources of contention, however, relates to New York’s State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQR), which covers a broad array of state and local permitting decisions.

SEQR passed in 1975 and was modeled after the federal National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) statute, which was signed into law on January 1, 1970. NEPA established a national framework for environmental review by requiring federal agencies to evaluate the environmental impacts of proposed actions before making decisions. In the wake of NEPA’s enactment, numerous states, including New York, passed their own environmental review laws, sometimes referred to as “little NEPAs,” with many states expanding upon the provisions of the federal law.

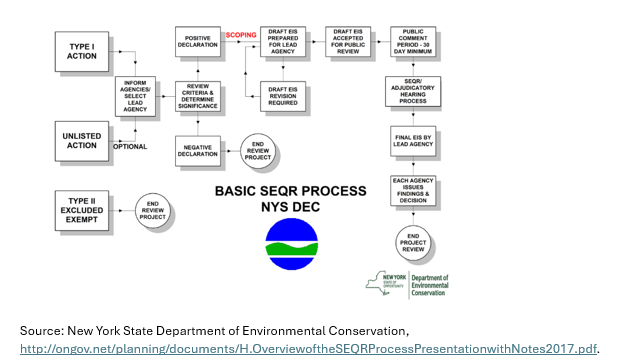

SEQR, like the New York UPA, distinguishes between two types of actions. In this case, Type I actions are expected to have significant impacts on the environment, and thus tend to be subject to more expansive environmental assessment form requirements (Full EAF), while Type II actions are not expected to have significant environmental impacts and therefore are exempt from further environmental review. Meanwhile, unlisted actions are items not falling in either category, and these usually require applicants complete an abbreviated Environmental Assessment Form (Short EAF). Once forms are submitted, the lead agency makes a significant determination, as to whether the project is likely to have significant environmental impacts. If the answer is yes, a full environment impact statement must be completed, (see figure 1).

The SEQR process is similar, but also differs from the federal NEPA process, in several important ways. Unlike NEPA, which applies solely to federal agency actions, SEQR mandates environmental reviews for both state and local agencies. Thus, permitting decisions at a local level can be subject to state environmental reviews. Additionally, SEQR has a more expansive threshold for requiring EIA, stipulating that one must be prepared when an action “is likely” to have a significant adverse environmental impact, whereas NEPA’s threshold for conducting an EIS is major federal actions that will be “significantly affecting the quality of the human environment.” If there is a finding of no significant adverse impact, the review stops, but on actions “which may have a significant effect on the environment”, an environmental impact statement must be prepared. Moreover, SEQR permits agencies to impose mitigation measures as a result of findings from environmental review, while NEPA is viewed as largely procedural in nature.

Problems Raised by SEQR

A 2013 Empire Center report notes several problems associated with SEQR. This uncertainty surrounding the duration of SEQR reviews can be a problem for project sponsors, as it hinders their ability to effectively plan and allocate resources. The Empire Center report recommended imposing deadlines to reduce delays and eliminating reviewing factors such as “community and neighborhood character” from environmental review, since this has little to do with the environment and is already covered by local zoning laws.

The complexity of SEQR is also evident in its extensive regulations, which span about 73 pages including various forms, and the comprehensive SEQR Handbook from the DEC, a lengthy document that runs about 212 pages in length and aims to guide agencies, project sponsors, and the public through the intricacies of the review process. The sheer volume of material associated with SEQR can be daunting and may discourage participation or hinder understanding among stakeholders.

In comparison to other states’ environmental review statutes, SEQR is also among the most stringent. A 2009 analysis by Ma et al. revealed that fewer than one-third of states have environmental review laws as comprehensive as SEQR.

Figure 1: The New York State SEQR Process

One can consider how SEQR interacts with the UPA discussed above. SEQR analysis helps inform permitting decisions in general, as well as the public commenting and hearing processes associated with actions at the DEC that follow the UPA. Both laws are also similar in the sense that they divide actions into major and minor categories. Both also make some effort to establish timeframes and structure to reviews. In this sense the statutes work together. However, SEQR can be seen as a law that is superimposed on top of other environmental laws and regulations. It is meant to provide a means by which environmental impacts of decisions are revealed and considered. However, in some cases, it also creates a redundant layer of review, since the focus of other environmental statutes is also environmental impacts. While the permit review and SEQR processes occur together, SEQR, like the federal NEPA statute, can still lead to protracted, open-ended review processes with difficult-to-anticipate schedules.

Recent Changes to New York’s Permitting Process

More than four decades after its signing, New York’s UPA has stood the test of time. While changes are relatively uncommon, it has nevertheless undergone some updates. For example, the regulations implementing the UPA (6 NYCRR Part 621) have been revised to provide further clarity on the permit application process. The number of general permits has been expanded over the years to cover a wider range of activities. The UPA also requires DEC to coordinate permit reviews with other state and federal agencies that may have jurisdiction over a project if an applicant requests coordinated review. Memoranda of understanding have been signed between DEC and other agencies to formalize these interagency coordination procedures at times.

The UPA’s implementing regulations have also been revised to account for new statutes that have passed since the UPA’s passage in 1977. For example, regulations now include provisions requiring considerations of factors such as climate risk, as well as environmental justice and impacts on disadvantaged communities. In 2003, the DEC adopted regulations formalizing the state’s environmental justice procedures as pertains to siting of major electric generating facilities.

Other changes have occurred over time that have added to the burden of environmental permitting in New York or favored some industries and companies at the expense of others. One notable change was the enactment of the Power NY Act in 2011. This legislation was designed to encourage investment in renewables and to facilitate the siting of new power plants, including renewable energy facilities as well as some fossil projects. The law established a new Article X process for the siting of electric generating facilities, which created a consolidated permitting process and set forth specific timeframes for review.

Likely due to a combination of local opposition to renewable projects, a lack of financial incentives for renewable projects, and the new Article X process primarily benefiting traditional energy producers as opposed to renewables, the 2011 law was largely unsuccessful at achieving its aims, and so another significant change was the creation of the Office of Renewable Energy Siting (ORES) in 2020, following passage of the Accelerated Renewable Energy Growth and Community Benefit Act. ORES was established to streamline the siting process for large-scale renewable energy projects, such as wind and solar farms. The law features timelines and one-stop shopping, such that the ORES office is responsible for consolidating the environmental review and permitting of these projects, with the goal of reducing the time and costs associated with the development of renewable energy infrastructure. Most recently, the legislature is considering steps to fast-track the siting of transmission projects deemed necessary to support the state’s renewable energy goals. One idea is to transfer permitting authority over transmission infrastructure from the New York Power Authority to ORES.

New York’s “Cumulative Impacts Bill” signed into law on December 31, 2022, further entrenched environmental justice considerations into the SEQR process. These rules built on existing rules that require applicants for certain permits to prepare an enhanced public participation plan and an environmental justice analysis if the proposed project is located in or may adversely affect a potential environmental justice area. While this guarantees more opportunities for public input during the permit review process, it also create more opportunities for delay.

Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

Passed around the same time, New York’s UPA and SEQR laws demonstrate how what are largely procedural statutes can create very different regulatory environments within their respective domains. UPA largely creates certainty for project applicants by creating a clear set of procedures and steps on the way to permit approval. On the other hand, while SEQR also creates a set of fixed steps, it has largely created uncertainty for project applications due to the open-endedness of reviews and the opportunities for obstruction and litigation the law creates. While UPA should probably be expanded to other domains, SEQR is almost certainly too broad. Although it no doubt uncovers some useful information, given how it overlaps with other existing environmental statutes, including the UPA, its scope could be severely curtailed.

A clear danger with New York’s environmental permitting process is that the state is favoring some politically connected industries and firms over others, as recent changes have sought to fast-track permitting for renewable energy projects while making the process perhaps more difficult and cumbersome for traditional energy sources as well as renewables in some cases. For example, the growing emphasis on environmental justice considerations and climate risk, while well-intentioned, has added yet more layers of review that can significantly delay projects and increase costs for applicants. More importantly, climate risk is not generally of concern for local development projects since almost no individual project, on its own, will have more than a miniscule impact on global temperatures. Environmental justice concerns can have merit, but these issues can be addressed during the public notice and hearing processes. There is little reason for additional emphasis on this factor beyond the general need for public input.

For states looking to reform their own environmental permitting processes, New York’s UPA may be more worth emulating, with its core principles of consistency, timeliness, and meaningful public participation. By standardizing procedures across a range of permits and activities, the law creates a more hospitable and predictable business environment, at least at one key state regulatory agency.

With respect to SEQR, when NEPA was passed there was an argument that it was insufficient, since it only covers federal actions. Hence, there was a belief that state and local government actions, including the issuance of many permits or zoning approvals, should be subject to a similar kind of environmental review as federal actions. In subsequent years, however, it has become clear that NEPA is a substantial barrier to infrastructure and energy development and is a magnet for litigation. Counterintuitively, environmental review often acts as an impediment to projects, like renewable energy projects, whose aim is to benefit the environment. That NEPA also overlaps with other federal and state environmental statutes can make the law sometimes unnecessary. The fact that many states do not have a “Little NEPA” statute that mirrors the federal NEPA law also casts doubt on the value of a statute like SEQR.

Short of repeal, however, other fixes are possible. Although the UPA only applies to certain proceedings before the DEC, SEQR could become subservient to process requirements under an expanded UPA, thereby increasing certainty and predictability for permits across a wide range of government actions. Additionally, the list of Type II projects could be expanded, or the analysis of certain environmental impacts could be deemed unnecessary. There is currently a bill pending in the NYS legislature that would exempt many small residential developments from SEQR and say that it is not necessary to analyze shadows cast by development structures or community character impacts. Time limits, such as under an expanded UPA, could also be imposed, similar to changes the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 made with the federal NEPA statute. Placing strict limits on who has standing to challenge decisions under SEQR could also help avoid frivolous litigation.

Recent efforts to create a separate permitting track for renewable or transmission projects, however, risk creating a politicized permitting environment where government is in the business of favoring some businesses or industries over others. There are some good features of the New York state environmental permitting process, but like with so many regulations, the process could be substantially improved with less law.

Acknowledgment: The author would like to thank Owen Yingling for helpful research assistance that contributed to this report.