Five Myths of Civil Forfeiture

Executive Summary

Every year, federal, state, and local government agents take—and permanently keep—billions of dollars of Americans’ property through civil forfeiture. The practice of civil forfeiture is deeply embedded in the nation’s economic and political system. It creates significant benefits for interest groups within government, such as policy makers, police officers, and prosecutors. Forfeiture reduces the taxes that policy makers would otherwise have to levy and captures funds for public safety budgets that law enforcement officials would otherwise have to pursue through legislative appropriations.

There is a fundamental tension between the government’s use of civil forfeiture and the rights of its citizens. Civil forfeiture allows police officers to seize property, and that seizure only requires probable cause for law enforcement officers to claim that the seized property is related to a crime. Prosecutors then can shift the ownership of the property to the government through litigation in civil court, even if the property owner never faced criminal conviction or even criminal charges. The danger that civil forfeiture poses to property rights and due process raises large questions about its legitimacy and fairness.

Civil forfeiture has also generated a mythology that functions as a justification for its use. It consists of a set of myths about civil forfeiture that are irreconcilable with basic facts.

These myths are as follows:

- Cash seizures, which become forfeitures, typically consist of hundreds of thousands of dollars;

- When property is seized, the owner has access to the courts to recover it;

- Seizure and forfeiture take place in accord with due process of law;

- Our justice system requires high standards of proof of wrongdoing for seizures and forfeitures to occur; and

- The injustices caused by civil forfeiture can be addressed by requiring a conviction in criminal court as a prerequisite to forfeiture litigation in civil court.

These statements do not describe reality; they obscure it. These five false narratives undergird an unjust status quo that leaves property owners unprotected and defenseless. This report aims to set the record straight. The available data and evidence demonstrate the reality of five very different propositions about civil forfeiture:

- A typical cash seizure and forfeiture ranges from several hundred dollars to a little over $1,000;

- When property is seized, the extraordinarily high rate of default judgments in forfeiture cases demonstrates that, in fact, property owners have little access to the courts;

- As seizure and forfeiture are practiced today, they cannot be squared with the due process of law;

- Seizure and forfeiture regularly occur without any evidence of wrongdoing presented in court; and

- The injustices caused by civil forfeiture are largely unaffected by conviction prerequisites in forfeiture statutes.

In short, there appears to be little substantial knowledge—among policy makers, the media, and the public—of the nature, context, and consequences of civil forfeiture. A more sophisticated understanding of the nature and operations of seizure and forfeiture could lead to significant reform of their most negative aspects.

Introduction

Every year, federal, state, and local government agents take—and permanently keep—billions of dollars of Americans’ property through civil forfeiture. The practice of civil forfeiture is deeply embedded in the nation’s economic and political system. It creates significant benefits for interest groups within government, such as policy makers, police officers, and prosecutors. Forfeiture reduces the taxes that policy makers would otherwise have to levy and captures funds for public safety budgets that law enforcement officials would otherwise have to pursue through legislative appropriations.

There is a fundamental tension between the government’s use of civil forfeiture and the rights of its citizens. Civil forfeiture allows police officers to seize property, and that seizure only requires probable cause for law enforcement officers to claim that the seized property is related to a crime.

Prosecutors then can shift the ownership of the property to the government through litigation in civil court, even if the property owner never faced criminal conviction or even criminal charges. The danger that civil forfeiture poses to property rights and due process raises large questions about its legitimacy and fairness.

Civil forfeiture has also generated a mythology that functions as a justification for its use. It consists of a set of myths about civil forfeiture that are irreconcilable with basic facts.

These myths are as follows:

- Cash seizures, which become forfeitures, typically consist of hundreds of thousands of dollars;

- When property is seized, the owner has access to the courts to recover it;

- Seizure and forfeiture take place in accord with due process of law;

- Our justice system requires high standards of proof of criminal wrongdoing for seizures and forfeitures to occur; and

- The injustices caused by civil forfeiture can be addressed by requiring a conviction in criminal court as a prerequisite to forfeiture litigation in civil court.

These statements do not describe reality; they obscure it. These five false narratives undergird an unjust status quo that leaves property owners unprotected and defenseless. This report aims to set the record straight.

Myths and Facts of Forfeiture This report provides empirical data about one particular type of seizure and forfeiture: the confiscation of cash. Although other kinds of property—for example, cars, guns, houses, and inherently illegal contraband—are regularly seized and forfeited, seizure and forfeiture of cash creates special dangers, largely because of money’s fungibility. Cash that is seized can be easily repurposed and redistributed into government budgets and then used for a variety of purposes.1

Specifically, this report analyzes the available state-level data on cash seizure and forfeiture. The evidence demonstrates that the myths of forfeiture that serve to justify its practice are at odds with real-world facts. (More information on data sources is provided in Appendix A.) The financial value of a cash seizure is unambiguous, so assessing its value poses no measurement difficulties.

That is not necessarily true when assessing the value of other kinds of property.

1. The Myth of the Typical Cash Forfeiture

The first myth of forfeiture: Cash seizures, which become forfeitures, typically consist of hundreds of thousands of dollars;

The reality: A typical cash seizure and forfeiture often ranges from several hundred dollars to a little over $1,000.

Most people do not sympathize with criminals. Furthermore, many people infer that someone who carries around large amounts of cash is engaged in criminal conduct. For example, consider this description of unwholesome behavior, voiced by an Arkansas state legislator during a 2019 committee hearing:

You have an individual that’s traveling through Arkansas headed back to Texas. They’re stopped by law enforcement, and law enforcement finds a secret compartment there on the vehicle. Inside that compartment is, say for an example, $200,000 in cash.

However, there is no contraband that’s found other than that money itself. Under current law, that money can be seized until that individual shows proof as to how he came into possession of that $200,000.2

Those who defend the established system of seizure and forfeiture often rely on such anecdotes to suggest that they describe a typical seizure, and that victims of seizure and forfeiture have it coming to them. During Rod Rosenstein’s tenure as deputy U.S. attorney general during the Trump administration, he issued a broad defense of civil forfeiture, claiming: “Most cases are indisputable.

When the police find $100,000 in shrink-wrapped $20 bills hidden in a suitcase, usually there is no innocent explanation.”3

However, publicly available data tell us that the typical cash forfeiture is much smaller than advocates of the practice regularly suggest. Most states either do not collect case-by-case data on seizure and forfeiture or do not make such data publicly available. But seven states do. This report surveys the available forfeiture data compiled

and produced by Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Hawaii, Kansas, Minnesota, and Tennessee.4 For each of these seven states, this report calculates the median cash forfeiture in that jurisdiction over multiple years. By definition, the median forfeiture size for a given year and jurisdiction tells us that about half of the cash forfeitures there are below that figure; similarly, about half are above it.5

Here is what the forfeiture data tell us.6

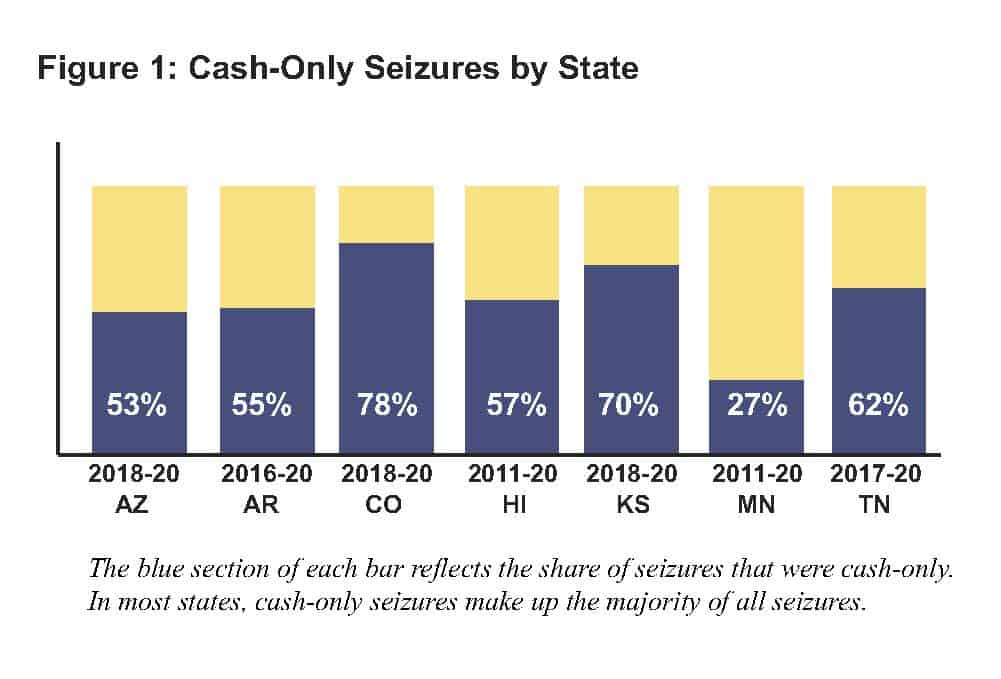

- In many seizure incidents, the only thing that is confiscated is

cash. In six of the seven states surveyed, cash-only seizures ranged from 53 percent to 78 percent of all seizures.6 The exception to this trend is Minnesota, in which cash-only seizures were just over 27 percent of all seizures.

(Figure 1)

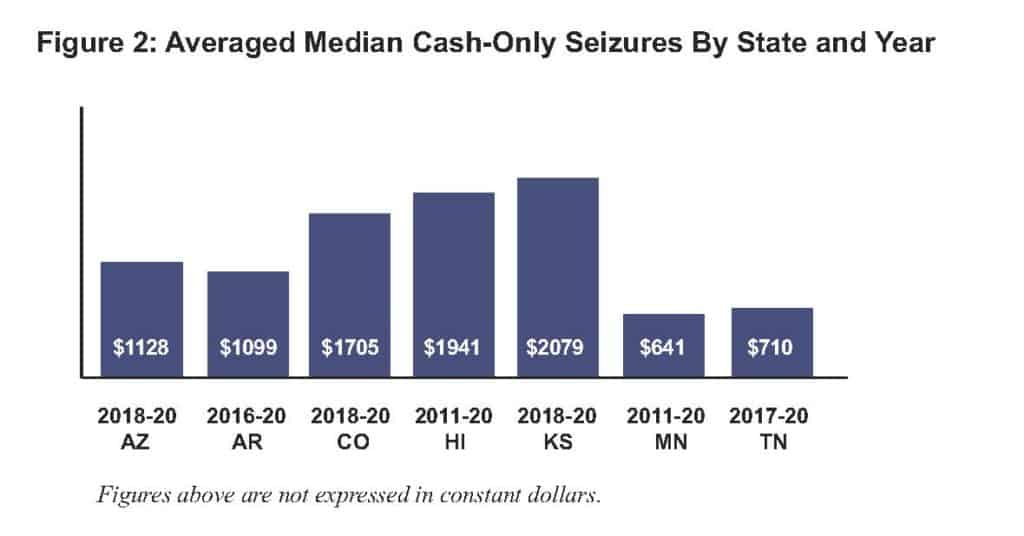

- With respect to cash-only seizures, the 2020 median seizure size in four states— Arizona, Arkansas, Minnesota, and Tennessee—when averaged together, is just over $1,000. Three other states—Colorado, Hawaii, and Kansas—had substantially larger median seizure sizes. (Figure 2).

Perhaps it is reasonable to infer that someone who is carrying $200,000 in cash is probably up to no good.

However, drawing the same inference about someone carrying cash of the magnitude described immediately above—say, around $1,000—is much more difficult to defend. In fact, countless legitimate commercial activities require carrying around large sums of cash—such as traveling to and participating in an auction to purchase used cars or restaurant equipment.

To illustrate, consider the recent seizure of Kermit Warren’s life savings. In November 2020, Drug Enforcement Administration agents seized over

$28,000 in cash from Warren while he was traveling through the Columbus, Ohio, airport. He was traveling home after inspecting a tow truck that he had considered buying.8

The data demonstrate that the first myth of forfeiture—that a typical cash forfeiture consists of hundreds of thousands of dollars—is wrong. In fact, the data demonstrate just the

contrary: that the typical cash forfeiture often ranges from several hundred dollars to a little over $1,000.

2. The Myth that Victims of Forfeiture Have Access to Justice

The second myth of forfeiture: When property is seized, the owner has access to the courts to recover it.

The reality: When property is seized, the extraordinarily high rate of default judgments in forfeiture cases demonstrates that, in fact, property owners have little access to the courts.

For over half a century, American courts have required the government to provide counsel to criminal defendants who face the prospect of incarceration but cannot afford to pay for an attorney.9 Knowledge of the right to counsel has become a bedrock part of our legal and popular culture. Given this background, it is easy to overlook a central fact of the seizure

and forfeiture process: No such right to counsel is available when civil seizure and forfeiture are involved, because the litigation takes place in civil, not criminal, court. Counsel for criminal defendants who face the prospect of incarceration is available as a matter of right, but counsel in civil seizure and forfeiture cases is only available to those who are willing and able to shoulder sizable attorneys’ fees. Such expenses are infeasible for many, a fact that is illuminated by extraordinarily high rates of default judgments.

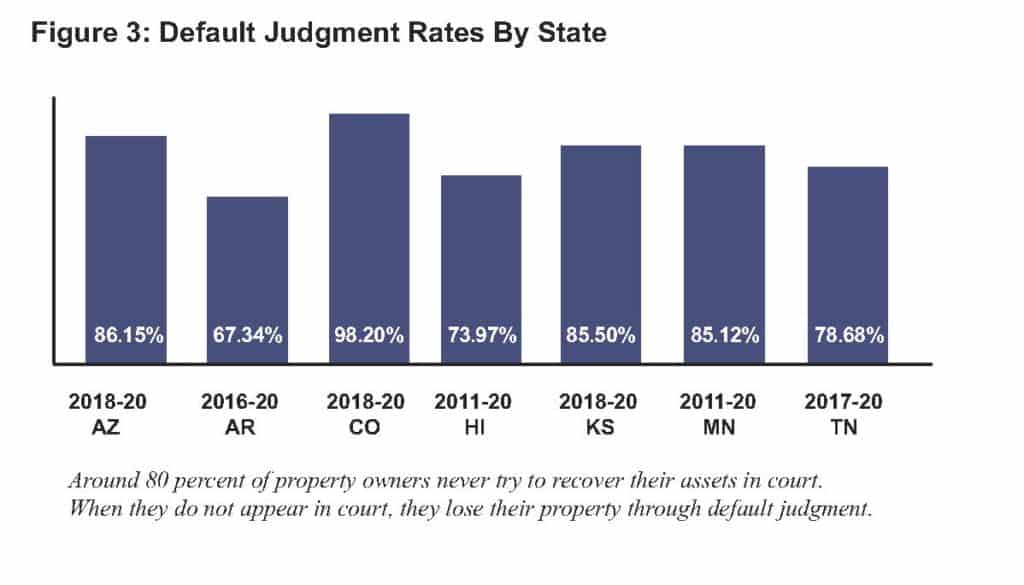

This report surveys the available court data from the seven states mentioned above in order to determine yearly rates of default judgments. The data show that when law enforcement officers seize cash, over 80 percent of the property owners do not contest the seizure in civil court.10 Instead, the court will enter a default judgment against the owner and automatically

transfer ownership of his or her property to the government. In four of the seven states surveyed in this report—Arizona, Colorado, Kansas,

and Minnesota—the average multi-year default judgment rates range from

85 percent to 98 percent. The average multi-year default judgment rates in Arkansas, Hawaii, and Tennessee are notably lower, at 67, 74, and 79 percent, respectively.11 (Figure 3) In short, more than 80 percent of owners of seized property never show up in court to recover it.

A default judgment takes place when two opposing parties are summoned to court, but only one shows up. The party that fails to appear automatically loses. The remarkably high rate of default judgments in forfeiture cases— more than 85 percent of forfeiture cases in the majority of the states surveyed—demands explanation. The fact that vast majorities of people who face forfeiture are simply walking away from their property is itself eyebrow-raising. If you knew that a court would give your property to someone else unless you showed up in court to claim it, why wouldn’t you appear? Some have argued that most victims of seizure never show up in court because their wrongdoing would be easily demonstrated there. As noted above, Rod Rosenstein, deputy U.S. attorney general in the Trump administration, provided a succinct explanation of the reason for high default judgment rates: “Most cases are indisputable.”12

However, Rosenstein’s argument misses a very important factor in property owners’ decision making: the extraordinary expense of hiring a lawyer. The expenses that a property owner must shoulder to recover his or her possession of it has consequences that may not be obvious. Consider the following examples.

- Suppose that Jones has had $900 in cash seized. He finds a lawyer who is willing to represent him at the seizure hearing, but the lawyer wants to be paid $2,500 for those services. When Jones realizes that, even if he wins his case, he will face a net loss of $1,600, he decides against hiring the lawyer and against appearing in court. Instead, he chooses to give up and accept his $900 loss.

- Suppose instead that Jones seeks a lawyer who charges on a contingency basis, paid as a percentage of the assets that are recovered. Jones finds a lawyer who requires the customary one-third share of recovery in successful cases, but the lawyer recoils when Jones tells him that the money at issue is $900.13 “If I represent you and win, I get paid $300,” the lawyer says. “It isn’t worth my time.”

As the two examples above illustrate, the greater the value of the seized property, the more feasible it becomes to hire a lawyer to recover one’s own property—either on a contingency or a flat-fee basis.

- Given that reality, it is reasonable to predict that we would see a smaller number of default judgments as the value of the forfeiture increases. This is generally true, but there is another wrinkle: the dynamics of fee-shifting. Some states have one-way “loser pays” forfeiture rules. That means that a property owner who is unsuccessful at recovering his or her seized property in court must pay some portion of the opposing side’s attorneys’ fees as well as his or her own.14 The specter of a surprise increase in litigation expenses can be expected to deter litigants.

One might argue that a victim of seizure who cannot afford an attorney (or just doesn’t want to pay for one) is free to avoid such costs by representing him- or herself in court. However, competent self-representation in such cases is often difficult—it may require the owner to file documents in court and comply with prosecutors’ discovery requests. Therefore, many property owners who are subjected to seizure and forfeiture might reasonably view self-representation as inadvisable.15

In short, the extraordinarily high rate of default judgments revealed by the available data, paired with the real-world dynamics of litigation, suggests that property owners face substantial obstacles when seeking access to justice. Defenders of the current system assume, without evidence, that criminal conduct by the vast majority of victims of forfeiture is beyond dispute. However, the sunken-cost dynamics that often dissuade innocent property owners from pursuing their right to their own property provides a better explanation. Furthermore, unlike the argument that most victims of forfeiture are indisputably guilty, the sunken-cost explanation does not rest on a presumption of near-universal criminality.

3. The Myth of Due Process of Law

The third myth of forfeiture: Seizure and forfeiture take place in accord with due process of law.

The reality: As seizure and forfeiture are practiced today, they cannot be squared with the due process of law.

When lawyers say “this violates due process of law,” they often mean “this is unlawful” or “this isn’t fair.” Illegality and unfairness are pervasive in seizure and forfeiture. There are at least three ways in which seizures and forfeitures are inconsistent with the due process of law.

First, the circumstances of typical cash forfeitures, as described above, strongly suggest that, for many property owners, there is no real access to justice. Property owners face a one- two punch. First they lose possession of their property through seizure. Then they discover that they have to pay for representation in forfeiture litigation to recover their seized property in civil court. When they learn that they must bear litigation costs that are larger than the value of the property seized from them in order to win, and when they consider the odds that they might fail, they give up. Given these circumstances, there are many instances of seizure and forfeiture in which no rational litigant would pursue recovery.

Second, as many Americans know, proof of criminal liability requires the showing of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. The heavy burden on prosecutors to establish guilt beyond a reasonable doubt is intended to protect innocent parties who, for one reason or another, become ensnared in the criminal justice system. The low standard of proof—typically a preponderance of evidence greater than 50 percent— required to prove wrongdoing in civil court will strike many as fundamentally unfair in forfeiture cases.

Third, the nature of seizure and forfeiture as it is practiced today is pervaded by anecdotal evidence that revenue concerns drive the behavior of law enforcement officers and other government agents. Consider Harjo v. City of Albuquerque, a 2018 case that provides an almost novelistic account of how a forfeiture program in New Mexico created pervasive conflicts of interest—specifically, conflicts between the interests of the property- owning citizen and those of a rapacious government.16

Albuquerque’s city ordinance on forfeiture allowed its law enforcement officers to seize vehicles operated by drivers who had committed any one of an array of offenses, including certain DWI offenses. As enforced, it resulted in the forfeiture of roughly two vehicles every day, which the city then sold at auction. The city’s forfeiture program generated roughly $1.5 million yearly in forfeitures, settlements, and fees— more than enough to fund the entire program. Meanwhile, surpluses routinely funded non-program expenditures such as the purchase of radar guns, patrol cars, and a new building.

The city employee tasked with determining whether any given vehicle could be seized and forfeited conducted an investigation largely consisting of database searches. That employee’s primary responsibility was to verify that the seizure occurred within city limits. There was no investigation of whether the vehicle in question was owned by the driver or of the possibility of a valid innocent-owner defense. In short, the “investigation” appeared, more or less, to presume liability.

In 2016, Albuquerque police seized Arlene Harjo’s two-year-old Nissan Versa. Harjo was not driving the car; she had loaned it to her son, who had told her that he wanted to drive it to the gym. However, the car was seized when her son was arrested for DWI while returning home after meeting his girlfriend.

Harjo requested a hearing before Albuquerque’s administrative hearing officer. She was connected with a city attorney who offered to settle the case if she agreed to pay $4,000 and boot her car for 18 months. That city attorney’s entire compensation, both salary and benefits, were paid for by the vehicle forfeiture program’s revenues.17

Part of the attorney’s job was to update the city government on “the program’s progress towards its annual performance measures for settlements, auctions, and auction revenues.” In fact, shortly after the attorney was asked to provide one such update, the city raised the attorney’s salary “to reflect exceptional performance.” The raise, like every dollar of program funding, was paid for by the forfeiture program.18

Harjo rejected the settlement offer. She then received a hearing before the city’s chief hearing officer, who determined that Harjo had failed to establish that she was an innocent owner. When Harjo’s multiple attempts to recover her car were reviewed in federal court, that court found that the hearing officer was “aware of the financial importance of the forfeiture program.”19

After Harjo lost at the hearing, the city filed a forfeiture complaint in state court. Harjo contested this procedure. In response, a paralegal employed by the city sent her “a packet of discovery requests, including several whose relevance the City’s [representative] could not explain.” The cover letter from the paralegal asked Harjo to sign a disclaimer that would extinguish any rights to her car. That paralegal’s salary was funded entirely by the forfeiture program.20

Ultimately, Harjo sued the city.21 Several months after she filed suit, the city dismissed its claim against her car when it determined that the car was outside city limits when it was seized. The city employee who conducted the background investigation for the initial seizure could have determined that the car was beyond the city’s lawful reach simply by looking at the relevant portion of the initial arrest report. The police report described the location of the seizure by naming a highway and a mile marker number.

That employee’s salary was funded entirely by the forfeiture program. As the court noted: “The police officer who seized [Harjo’s] car … mentioned the mile marker number at the hearing, and the city attorney included the mile marker number in the complaint that he filed in state court.”22

However, the dismissal of the claim did not extinguish the court’s constitutional inquiry. The court found that the city had an unconstitutional incentive to prosecute forfeiture cases because the resultant revenues accrued in a self-financing special fund that allowed it to spend surplus revenues on other discretionary programs; it based its holding on the guarantee of due process of law ensured by the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Notably, the program’s revenues did not go to the city’s general fund, where they could be allocated by city councilors into various programs via the normal appropriation process. In the view of the court, the self-funding nature of the program turned the city government into something like a “rubber stamp” that did not exercise meaningful budget review.

In short, the city’s forfeiture program had troubling similarities to a profit- oriented investment—the more resources were assigned to the program, the more revenues it produced. This kind of public enterprise, when coupled with political independence—namely, its “de facto power over its spending”— resulted in unconstitutional incentives.23 The court also found that the use of the innocent-owner defense in this context unconstitutionally required “a car owner to prove his or her innocence.”24 Essentially, because the city’s prior burden to show probable cause required it “to prove nothing about the car owner” —as distinct from the typical, “robust” burden that prosecutors must typically shoulder to demonstrate guilt—the assignment of the burden of proof to property owners to demonstrate innocent ownership was itself constitutionally defective.25

Next, consider the following case from Tennessee. An extensive investigation by NewsChannel 5 of Nashville discovered a curious fact about a drug task force that patrolled Interstate 40. Like many federal highways, Interstate 40 is a major drug-trafficking artery. Typically, couriers drive east while carrying drugs, and they drive west while carrying money derived from the proceeds of the drug trade.

Notably, task force officers made over 90 percent of their stops on the westbound portion of the highway, even though one might think that those officers would be equally likely to stop motorists on either side of the highway.26 A possible explanation for this bias toward westbound stops is that law enforcement officers surmised that they were more likely to find money in vehicles traveling westbound. If this explanation holds water, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the priorities of the drug task force rested more on confiscating money than on confiscating drugs.

Apparently, the revenues from I-40 cash seizures were so large that other law enforcement agencies sometimes behaved unprofessionally in their zeal to capture particular arrestees. In fact, the investigation discovered recordings of an incident in which personnel from law enforcement bodies that shared jurisdiction—Dickson Interdiction Criminal Enforcement (DICE) and the 23rd Judicial District Drug Task Force (DTF)—got into a screaming match peppered with threats, insults, and obscenities over who would work an arrest:

23rd DTF Officer: “Leave me the f***k alone!”

DICE Officer: “Let me tell you something …”

23rd DTF Officer: “Punk!”

DICE Officer: “You ever come up [on] me and try to wreck me out again, it will be your last time. You understand?”

Such turf battles continued until the two agencies produced an agreement containing the dates that each agency would have priority on the westbound lanes—an agreement that resembled a contract between colluding business- people determined to dampen competition by dividing commercial territories among themselves.

These anecdotes show that seizure and forfeiture actions by law enforcement are sometimes driven less by crime- fighting and public safety concerns than by the goal of raising revenue.

In fact, some law enforcement representatives have been willing to admit this publicly. In 2019, South Carolina Sheriff’s Association

Executive Director Jarrod Bruder notoriously argued that his state’s civil forfeiture system provided an additional, and appropriate, boost to drug enforcement efforts. According to Bruder, law enforcement officers probably would not pursue drug dealers and their cash with the same degree of energy without the profit incentive that the civil forfeiture system provides. If law enforcement agencies are prevented from profiting from civil forfeiture, then, Bruder asked, “what is the incentive to go out and make a special effort? What is the incentive for interdiction?” 27

Similarly, during a 2016 legislative committee hearing in Wisconsin on a measure that would divert forfeited cash away from law enforcement budgets and toward school budgets, Eau Claire Sheriff Ron Cramer asked:

What is the money used for in the school fund? What advantage is there for the district attorney or law enforcement to make any seizures that all the proceeds revert to another agency?28

Such rhetorical questions suggest the existence of a dangerous incentive system. A government scheme that awards law enforcement officials with bounty payments for their budgets whenever they detect misconduct seems likely to lead to disastrous outcomes.

Moreover, there is widespread circumstantial evidence that revenue concerns drive law enforcement behavior in multiple areas, rather than being limited to the realms of seizure and forfeiture. One study of North Carolina court data found that “significantly more tickets” were generated by localities when their budgets were strained, which suggests that traffic enforcement was “used as a revenue-generation tool rather than solely a means to increase public safety.”29 A 2021 New York Times investigation found that “at least 20 states have evaluated police performance on the number of traffic stops per hour.” (The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration issues roughly $600 million in grants each year. Although the agency does not encourage or require quotas or targets for traffic stops in its grant evaluations, the number of traffic stops performed per hour is a common performance measure used by grant applicants.)30

The Times article described multiple instances in which city budgets appear to depend on fines from traffic violations:

In Bratenahl, Ohio, the town government is so dependent on traffic enforcement that the police chief castigated his officers as “badge-wearing slugs” in an email when a downturn in ticket writing jeopardized raises. Ticket revenue helped finance sheriff’s equipment in Amherst County, Virginia; a “peace officers annuity and benefit fund” in Doraville, Georgia; and police training in Connecticut, Oklahoma, and South Carolina.31

Those who argue that public safety is the fundamental goal of law enforcement officers when ticketing violators will find one particular Oklahoma law enforcement practice especially provocative. Apparently, reports the Times, some officers there “no longer cite drunken motorists for driving under the influence, and instead issue less-serious tickets that keep the drivers out of district court and generate more money for the town.”32

Whenever law enforcement officials appear motivated by self-interested concerns, the possibility of a constitutional due process problem looms. Any constitutional inquiry into whether self-interested government employees might create a biased and unfair process would rest on how closely related the employees’ actions are to the bias that is injected into adjudication.33 But it should be evident to lawyers and non-lawyers alike that a civil forfeiture system that links its results to private benefits for public employees risks being both unfair and unconstitutional.

Similarly, many people would see Indiana’s civil-forfeiture system, which farms out its cases to private attorneys who then prosecute on a contingency-fee basis, as morally and constitutionally problematic. Indiana’s administration of civil forfeiture grants private sector prosecutors a personal financial stake in each case’s outcome, requires private-sector attorneys to be paid on a contingency- fee basis, and prevents flat-fee or salary-style compensation.34 Indiana is now the only state in the nation that allows such a scheme.

A similar civil-forfeiture compensation structure for private-sector attorneys was struck down in Georgia nearly a decade ago. Some jurisdictions in Georgia carried out an Indiana-style scheme until 2012, when the Georgia Court of Appeals held those arrangements “repugnant” and “void as against Georgia public policy” because they gave private attorneys a personal financial stake in forfeiture actions.35 As the Georgia court noted, the responsibility of a public prosecutor is “not merely to convict,” but “to seek justice,” because of his or her “additional professional responsibilities as a public prosecutor to make decisions in the public interest.”

In short, our everyday understanding of the basic fairness we are entitled to in the judicial system is, at best, in extreme tension with the norms and practices of civil seizure and forfeiture.

4. The Myth of Probable Misconduct of Forfeiture Victims

The fourth myth of forfeiture: Our justice system requires high standards of proof of criminal wrongdoing for seizures and forfeitures to occur.

The reality: Seizure and forfeiture regularly occur without any evidence of wrongdoing presented in court.

The belief that most victims of civil forfeiture are, in fact, guilty of wrongdoing—“bad guys”—is widespread. As noted above, some senior government officials who advocate in favor of the current civil forfeiture system have even argued that, by and large, there is no such thing as seizure of property from innocent parties. However, the reality of forfeiture is that wrongdoing is regularly presumed rather than proven.

The American criminal justice system requires proof of a very high order— guilt beyond a reasonable doubt— because abuses of government power are much more likely to occur if a lesser quantum of proof is required.

Some civil forfeiture advocates have argued that the lesser quantum of proof required by the practice is a feature that allows for rapid and efficient administration of justice. However, a better perspective—one more in line with American historical and cultural norms—is that concluding that criminal conduct has occurred while sidestepping the traditional methods of that conduct’s identification, and its attendant safeguards, is not a feature; it’s a bug.

In fact, seizure and forfeiture regularly occur without any evidence of wrong- doing presented in court. The explana- tion of this phenomenon requires brief elaboration.

- Seizure. A law enforcement officer’s seizure of property requires probable cause. As the United States Supreme Court has explained, the officer must reasonably believe there is some probability of criminal activity36—more precisely, that there is a “fair probability” of such misconduct.37 Probable cause is not a “technical” judgment. It rests on the “factual and practical considerations of everyday life,”38 and is “incapable of precise definition or quantification into percent- ages.”39 In other words, probable cause does not require the officer to observe misconduct as such. Rather, the officer who seizes property may infer that criminal conduct is a possible explanation of what has been seen. One practical implication of the use of the probable cause standard is that utterly innocent behavior can be theorized into the justification for an officer’s seizure.

- Forfeiture. Forfeiture is the legal process by which ownership of property is transferred to the government. As discussed above, the extraordinarily high rate of default judgments in civil forfeiture cases has multiple consequences: one of those consequences is that most civil forfeiture cases never receive any judicial scrutiny at all. There are many instances in which (a) the factual evidence of probable cause that supports an officer’s seizure or (b) the factual evidence that supports a prosecutor’s criminal charge would be insufficient to justify forfeiture—but in the world where a civil court is never required to examine the case against forfeiture, that doesn’t matter.

The Institute for Justice’s (IJ) recent survey of Philadelphia’s citywide forfeiture program, which was dismantled in 2018 under a consent decree, found that the city seized property from over 30,000 people, most of whom were never found guilty of any wrongdoing. That survey, which included data from a representative sample of the forfeiture program’s victims, found that roughly 25 percent of them were found guilty or pled guilty to wrongdoing, but that 69 percent of them had previously owned property that was lost forever because of forfeiture.40

Notably, Pennsylvania law allowed police and prosecutors to plow every dollar of forfeiture proceeds back into their own agencies’ budgets. The IJ survey notes that this created a “strong financial incentive” for law enforcement personnel to seize property. Involvement in such a program would also likely create a strong psychological incentive for law enforcement officers to justify the morality or fairness of their work.

Upton Sinclair famously noted that, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”41 In fact, civil forfeiture—coupled with the budget practices it creates—literally encourages law enforcement personnel to avoid understanding its implications for criminal justice. Rather, police officers and prosecutors are encouraged to view civil forfeiture as a crime control enterprise, even though the civil forfeiture process lacks the conventional protections that are extended to those accused of criminal conduct. When the attendant financial and psychological incentives are taken into account, the dangers of injecting civil standards of proof into procedures that ostensibly punish only criminals become increasingly apparent.

5. The Myth of the Effectiveness of Conviction Provisions

The fifth myth of forfeiture: The injustices caused by civil forfeiture can be addressed by requiring a conviction in criminal court as a prerequisite to forfeiture litigation in civil court.

The reality: The injustices caused by civil forfeiture are largely unaffected by conviction prerequisites in forfeiture statutes.

In recent years, several states have attempted to reform civil forfeiture, and the injustices it entails, by enacting what has been called a “conviction prerequisite” into law. Generally speaking, a conviction prerequisite requires prosecutors to obtain a conviction of a property owner or possessor in criminal court before forfeiture litigation can occur in civil court. In fact, however, the conviction prerequisites that most states have enacted are essentially ineffective.

In order to appreciate why these provisions do not work, it is helpful to recall the legal distinction between substance and procedure. Generally, many of the rights we have—for instance, our rights to use and possess property—are called substantive rights. In contrast, some of the rights we have are procedural in nature—for instance, the right of the accused to a speedy and public trial. Sometimes the protection of substantive rights rests on procedure—for example, a defendant whose rights can only be exercised through participation in a judicial proceeding will be without those rights if he or she fails to participate.

This illuminates a significant defect of conviction prerequisites: They create rights that cannot be realized unless the property owner participates in forfeiture litigation in civil court. A conviction prerequisite is typically accompanied by a set of exceptions.

The provision will not operate if the exception occurs. The relevant exception here is that if the property owner fails to appear in court to defend his or her own property, then the conviction provision will not go into effect. Most conviction provisions in state statutes contain this noteworthy exception. In short, if your property is seized and potentially subject to forfeiture, you are required to show up in court in order to benefit from a conviction prerequisite.

This exception underscores the relevance of high default judgment rates (as discussed above): To the extent that the forfeiture system tolerates high percentages of default judgments, the conviction prerequisite is largely irrelevant. The concrete evidence for the irrelevance of conviction provisions is perhaps best illustrated by recent state legislative battles in Arkansas and their outcomes.

When the Arkansas legislature passed civil forfeiture reform in 2019, it was quite a contrast to the bitter legislative fights that body had endured over civil forfeiture reform in previous sessions.42 That part of the 2019 legislative session contained two big differences from those of years past.

First, the 2019 reforms embodied notably different policies from those proposed during previous sessions, and the state prosecuting attorneys’ association supported the 2019 reforms.

Second, previous sessions saw proposals to combine criminal prosecution and forfeiture litigation into one blended procedure. In contrast, the 2019 proposal established a conviction prerequisite in criminal court for forfeiture litigation in civil court. In other words, the 2019 reforms left the two-track aspect of Arkansas’ justice system largely untouched.

Regrettably, even some reform-minded analysts and commentators who are broadly skeptical of civil forfeiture overlooked the fundamentally ineffective nature of Arkansas’ conviction-condition reforms. A laudatory March 2019 story in Reason entitled “Arkansas Legislature Effectively Votes to Abolish Civil Forfeiture,” contained this eyebrow- raising passage:

Jenna Moll, the deputy director of the Justice Action Network, a criminal justice advocacy group, called the passage of the bill “a watershed moment for forfeiture reform efforts in the United States.”

“To see two chambers of the Arkansas legislature pass this legislation unanimously is truly remarkable,” Moll says. “Arkansas has now truly set the marker for other states seeking to protect property rights and improve due process for their citizens.”43

The story’s sub-headline read: “Arkansas joins three other states in requiring police secure a conviction before they can seize a person’s property.”44

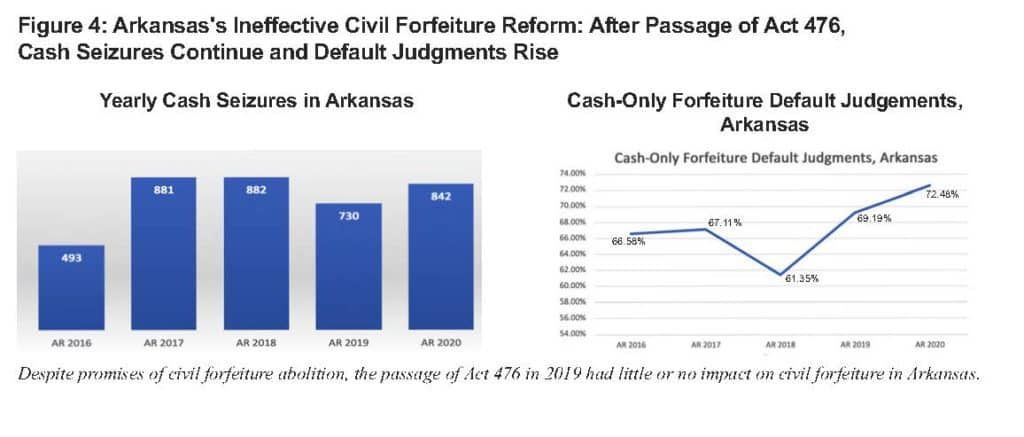

Nonetheless, despite the laudatory claims quoted above, there is no real sense in which Arkansas abolished civil forfeiture. (Figure 4: Graphic of 2018-2020). The statute the Arkansas legislature passed bears no resemblance to the measures to eliminate civil forfeiture that Nebraska, New Mexico, and North Carolina had previously enacted.45 (Those are the “three states” to which the Reason article referred; they had previously ended civil forfeiture and replaced it with a forfeiture process that is part of criminal prosecution in a criminal court. A fourth state, Maine, abolished civil forfeiture in 2021.)

It is fair to say that a slight dip in forfeiture incidence followed the passage of Arkansas’ law, but that dip appears insignificant from a historical perspective. Notably, of the five years of Arkansas’ civil seizures and forfeitures analyzed in this report, both the highest default judgment rate for cash seizures and the largest median size of cash forfeitures occurred in 2020, the year after the reform’s passage. The conclusion that Arkansas “abolished” civil forfeiture is not simply overheated; it is indefensible.

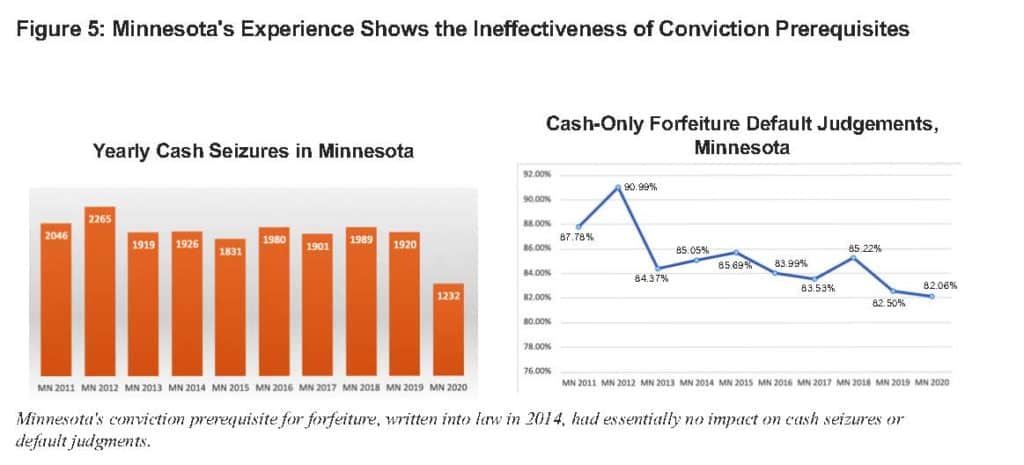

Arkansas is now one of 16 states that ostensibly require a conviction prerequisite for civil forfeiture.46 Unfortunately, the evidence that such provisions “truly set the marker” for constructive change is absent. Arkansas’ experience—namely, that conviction provisions have no real effect on seizure and forfeiture—is characteristic. The experience of the only other state surveyed here that wrote a conviction provision into law—Minnesota in 2014—provides further evidence of the impotence of these provisions. Six years after passage of this reform, seizures and defaults continued more or less unchanged. (Figure 5)

Conviction provisions are at best a weak protection of the rights of property owners. Depending on how the provision is written, forfeiture is typically permitted whenever anyone is convicted of a crime that is related to the property, whether it is the owner or someone else. For instance, recall the case of Arlene Harjo, whose car was forfeited after she loaned it to her son, who was then arrested for DWI. New Mexico’s forfeiture program essentially penalized her for her son’s actions.

Other states’ conviction provisions only exclude narrow categories of property from forfeiture. For instance, New Jersey’s conviction provision excludes cash forfeitures greater than $1,000.47 A similar measure, enacted in July 2021, that excludes cash totaling less than $1,500 from forfeiture went into effect in Minnesota on January 1, 2022.48

In short, the facts demonstrate that conviction prerequisites that keep forfeiture litigation in civil court have little or no effect, and that these provisions’ impact on the fairness or the consequences of forfeiture programs is largely insignificant.

Paths to Real and Lasting Reform The American system of seizure and forfeiture that has evolved over the past few decades is profoundly unjust. It tramples the rights of large numbers of people and denies them access to the courts. The system’s problems should invite consideration of, at the very least, the three reforms described below.

A first reform, of primary importance, is to establish a criminal forfeiture system, as opposed to a civil forfeiture one. A criminal forfeiture system simultaneously adjudicates both the criminal liability of the defendant and the defendant’s rights to the seized property. In many respects, it is not subject to the problems described above. As a formal matter, there is no access to justice problem for indigent defendants who face the prospect of incarceration. Under the 1963 Supreme Court ruling of Gideon v. Wainwright, such defendants do not have to cover the cost of their own defense. In contrast to the current civil forfeiture system, defendants would not be deterred from appearing in court under a criminal forfeiture system because of cost concerns.49 A stream- lined and unified criminal forfeiture system would help avoid waste of government resources by allowing the resolution of more issues with fewer procedures and vastly ameliorate the problems of small-dollar forfeitures and high default rates discussed above.50 As noted, Maine, Nebraska, New Mexico, and North Carolina have adopted this system.

A second reform is to require that forfeited assets go to a state’s general fund, rather than to supplement the budgets of police agencies and prosecutors’ offices. That would reduce the systemic incentives, described above, that appear to encourage some degree of personal and political corruption among public employees.

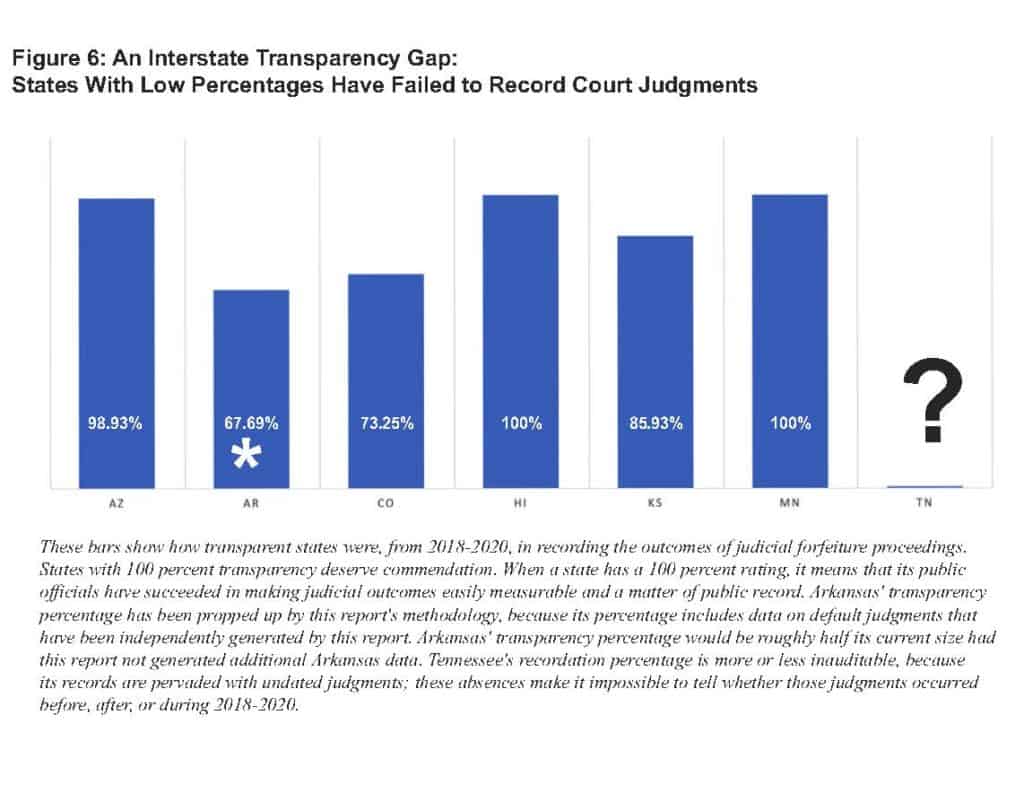

A third reform is to require greater transparency in seizure and forfeiture processes. That would allow for better-grounded findings and policy making than the status quo, which, as discussed above, only allows for detailed findings of seizure and forfeiture data from a handful of states. Relatedly, jurisdictions that have established transparency measures would do well to monitor how well their agents are complying with those mandates. Some gaps in datasets that are supposed to be fully transparent suggest that some state governments have room for improvement in this area. (Figure 6)

Conclusion

The mythology that has grown up around civil forfeiture works to obscure reality, rather than illuminate it. In fact, the available data and evidence demonstrate the reality of five propositions about civil forfeiture:

- A typical cash seizure and forfeiture ranges from several hundred dollars to a little over $1,000;

- When property is seized, the extraordinarily high rate of default judgments in forfeiture cases demonstrates that, in fact, property owners have very little access to the courts;

- As seizure and forfeiture are practiced today, they cannot be squared with the due process of law;

- Seizure and forfeiture regularly occur without any evidence of wrongdoing presented in court; and

- The injustices caused by civil forfeiture are largely unaffected by conviction prerequisites in forfeiture statutes.

In short, there appears to be little substantial knowledge—among policy makers, the media, and the public—of the nature, context, and consequences of civil forfeiture. A more sophisticated understanding of the nature and operations of seizure and forfeiture could lead to significant reform of their most negative aspects.

Appendix A: Data Collection and Methodology in the Several States

For the most part, this report relies on data from public sources, as described below.

- Arizona. The Criminal Justice Commission provides quarterly seizure and forfeiture reports on its website that date back to 2018.51

- Colorado. The Department of Local Affairs provides, twice a year, seizure and forfeiture reports on its website that date back to 2017.52

- Hawaii. The Department of the Attorney General provided information on seizures and forfeitures to this report’s author in response to a records request. This report relies only on that state’s data from 2011 onward, although previous data are also available.

- Kansas. The Bureau of Investigation provides annual seizure and forfeiture reports on its website that date back to 2019.53

- Minnesota. The Office of the State Auditor provides a yearly report on asset forfeitures, dating back to 1996, and the yearly datasets on which the report relies, dating back to 2018, on its website.54 In response to a records request, an official from that office also provided the datasets from 2011 to 2017 to this report’s author. This report relies on that state’s data from 2011 onward, although previous data are also available.

With respect to these five states, this report uses the data described above to calculate the following statistics for a given year:

- (a) Total number of seizures;

- (b) Total number of all-cash seizures (seizures that produce something besides cash, in all or in part, are not counted for these purposes);

- (c) Total number of all-cash seizures about which we have some knowledge of their outcome (seizures about which we know whether or not some party appeared in court to contest the seizure, according to public records);

- (d) Total number of all-cash seizures about which we lack knowledge of their outcome (seizures about which we lack information whether or not some party appeared in court to contest the seizure);

- (e) Total number of all-cash seizures that we know resulted in a default judgment;

- (f) Total number of all-cash seizures that we know resulted in some outcome besides a default judgment;

- (g) Percentage of default judgment outcomes for all-cash seizures about which we have some knowledge of their outcome;

- (h) Median amount of all-cash forfeitures; and

- (i) Percentage of the all-cash forfeitures about which we have some knowledge of their outcome— expressed as the ratio produced by dividing the total number of all-cash seizures about which we have some knowledge of their outcome by the total number of all-cash seizures—namely, c/b.

For any given state and year, c+d=b, e+f=c, and e/c=g. The median figures described by h rest on the total figures contained in b. Ultimately, the relevant sets of the nine statistics described above were used to calculate the charts and graphs contained in this report.

Inevitably, databases compiling reports from multiple law enforcement agencies attempting to describe thousands of instances of seizure and forfeiture will pose problems of interpretation. This report attempts to draw the most reasonable inferences from the available data.

Generally, when the dataset suggests that a defendant, after receiving notice of a pending forfeiture, did not file an answer or otherwise contest the case, this report treats that occurrence as a default judgment.

This report does not treat as a default judgment: a) when the dataset suggests that the parties agreed on the disposition of the seized property, because an agreement suggests that both parties resolved what began as an adversarial process, and b) when the dataset suggests that a hearing occurred as a consequence of a seizure, because the existence of a hearing suggests that both parties participated in an adversarial process.

When the data provide no information or extremely minimal information on some particular instance of seizure or forfeiture, this report does not count that as an instance of seizure or forfeiture.

The available data from Kansas appear to include only half of 2019, so it may be reasonable to give less weight to the findings that pertain to that state for that year.

Finally, the circumstances of the dataset from Arkansas and Tennessee are categorically different from those of the datasets from other states. Those special circumstances are described in Appendix B.

Appendix B: Data Collection and Methodology: The Special Cases of Arkansas and Tennessee

In a nutshell, it appears that some of the Arkansas and Tennessee data requested are missing or were never recorded, so the author made certain assumptions about the dataset for those two states as described below.

Arkansas

This report’s account of civil seizure and forfeiture in the State of Arkansas would not have been possible without the assistance provided by the Arkansas Center for Research in Economics (ACRE), housed at the University of Central Arkansas’ College of Business.

This report’s Arkansas findings began with the analysis of datasets that describe seizure and forfeiture from the State of Arkansas that were supplied by ACRE. ACRE has made a series of records requests from Arkansas covering previous years, and provided those historical records to the author. Those records purport to describe the details of each instance of seizure and forfeiture. However, some Arkansas state government agencies do not preserve their records indefinitely, so it is unclear to what extent current requests for previous years’ data submitted directly to those agencies would be successful.

Disappointingly, a review of the historical records obtained by ACRE suggested that those records were largely incomplete and inaccurate. It appeared that the records had failed to accurately label, classify, or identify many cases of seizure and forfeiture. Furthermore, it appeared that the records had mislabeled many cases that were default judgments or agreed-upon orders, such that the outcomes of those civil cases were pervasively misidentified. In order to create a more comprehensive and accurate dataset, this report relied on research from Marc Kilmer, who examined electronic records from thousands of cases of seizure and forfeiture by means of the Administrative Office of the Court’s Public CourtConnect website.55

Generally speaking, the inaccuracies in the original records made it difficult or impossible to draw

well-grounded conclusions about roughly two-thirds of the instances of seizure and forfeiture catalogued in Arkansas. However, thanks to Kilmer’s research, the fraction of reliable accounts of seizure and forfeiture in Arkansas in available historical records changed from about one-third to about two-thirds. Kilmer’s research and coding efforts helped to create a much more accurate and representative dataset that generated findings that are comparable to those from other states. Those findings include case-by-case calculations for Arkansas denominated a through i that are analogous to those described in Appendix A above. This information could not have been made accessible without the assistance of ACRE, which generously provided a research grant to cover the costs of Kilmer’s work.

Tennessee

Some time after submitting a records request for civil seizure and forfeiture data dated 2010 or later to the Tennessee Department of Safety and Homeland Security, the author received an extensive set of spreadsheets containing a somewhat opaque dataset.

The dataset appeared to be a compilation of 78,763 seizures, some dating back to 2009. A departmental spokesman explained that the current record keeping system dates back to 2016, but data from a previous system were imported that likely covered at least a decade before that. Therefore, comparing data produced before 2016 to data produced after 2016 posed significant problems of interpretation, because it appeared likely that events might be coded or identified differently in those two time periods even if they were substantively identical. Furthermore, a substantial number of the recorded seizures were not dated at all, which made it impossible to identify in what year they occurred.

However, it was possible to identify a substantial portion of the database—36,627 seizures—in most of the seizures that appeared to be dated clearly from 2016 to 2021. This portion of the database was grouped together and arranged in rough chronological order, which suggests a relatively low degree of coding variance and coding error. There were other seizures scattered throughout the database that were also dated 2016 to 2021, but those records were not taken into account for this project. As noted, because of Tennessee’s 2016 change in its record keeping system, this report uses only the data from 2017 to 2020.

This report’s account of seizure and forfeiture in Tennessee would not have been possible without the assistance provided by the Beacon Center of Tennessee. Several members of its staff tirelessly provided the author with assistance in records requests and interpretation of the data that was provided.