Global Infrastructure Permitting

A Survey of Best Practices

Executive Summary

The construction of major infrastructure projects, such as power plants, highways, and ports, is heavily regulated. In major industrial economies, such projects typically require complex permits, which in turn entail extensive study of potentially significant environmental impacts. Securing the permits needed for construction and operation and completing the related environmental impact assessments (EIAs) often takes more time than actual construction and can even be more expensive. The costs, delays, and uncertainties of the process are major hurdles to the efficient deployment of needed infrastructure.

Permitting inefficiency deprives Americans of the modern infrastructure they need and deserve. It also makes any transition to net-zero carbon emissions impossible, regardless of whether that goal is even advisable. The permitting risk entailed in major infrastructure investments is poorly understood and reduces many investment decisions to speculation, which in turn inhibits infrastructure investment. That has led to a structural infrastructure deficit that is constricting supply and raising prices across the economy.

In the United States, there is a growing bipartisan consensus that the federal regulation of infrastructure permits and environmental reviews must be reformed. Congress has been making marginal improvements to the process for years, leading to the permitting reforms of the recent Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, which raised America’s statutory debt ceiling.1 Though significant, the recent changes bear the hallmarks of earlier efforts: They are tinkering at the margins of a major problem that needs a more comprehensive solution.

One reason that congressional deliberations have not produced more thoroughgoing changes is almost certainly the insular nature of the debate: Few American policymakers have any idea what other countries are doing to improve their infrastructure regulations. That is a dangerous lacuna, and the purpose of this report is to help fill it.

Infrastructure deficits are a worldwide problem. Developing countries suffer from it in obvious ways, but even the most advanced economies struggle with “infrastructure governance.”2 Governments are waking up to the fact that inefficient infrastructure regulation is a significant competitive disadvantage. There appears to be growing international competition to improve regulations for infrastructure delivery. Some countries have moved further and quicker than others in advancing infrastructure modernization while still protecting the environment, especially in particular sectors such as renewable energy and transportation. This report surveys those reforms in the hopes of enriching U.S. policymakers’ deliberations with new perspectives and ideas.

This report discusses the economic impact of permitting risk and the challenge it poses for national policy priorities, from deploying adequate infrastructure to achieving international emissions targets. The permitting and environmental review regimes of selected major economies are examined for best practices. The report concludes with a summary of best practices and recommendations for U.S. policymakers.

Permitting risks, including political and regulatory risks, are difficult to quantify. Longitudinal data on projects, from proposal to outcome, are often lacking. The lack of understanding regarding the risks of infrastructure investments is an obstacle to infrastructure investment and results in resource misallocation. It is crucial to collect comprehensive data on permit application outcomes in order to make the risks of infrastructure investment quantifiable, otherwise investment decisions will continue to face often prohibitive uncertainty.

Most studies outlining pathways to net-zero carbon emissions offer some estimate of transition costs. None of them consider the impact of permitting risk on capital formation, however, implying a systematic underestimation of both the cost and feasibility of a net-zero transition. As this report shows, under current law, the United States simply cannot authorize renewable energy infrastructure at the scale and speed necessary to meet its stated emissions goals. Without permitting reform, the U.S. will not come close to meeting those commitments.

In the meantime, the U.S. is increasingly falling behind major competitors in the quality of its infrastructure. With China on the rise, that is not something America can afford. Like companies in the private economy, nations create wealth through innovation. The prosperity of a country is not determined by natural resources, but by the innovative allocation of human resources.

To maintain their competitive advantage, nations must maintain favorable factors of production such as skilled labor and infrastructure. A simple and predictable legal framework is crucial for encouraging risk-taking and private investment. Complex regulations and unpredictable legal systems can hinder innovation and economic growth, creating developing-world risks for even the most advanced economies.

This report examines permitting and EIA processes in the United States, European Union, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and China. It summarizes recent and ongoing efforts to enhance permitting efficiency, with an emphasis on energy infrastructure.

While government should never pick winners and losers in the private economy, sector-specific reforms are often valuable sources of general reforms. Based on the global best practices surveyed in this report, the U.S. Congress should enact sweeping reforms of the permitting process for major infrastructure projects. Drawing on those examples, this report makes urges Congress to consider key innovations:

- A single agency acting as a “one-stop-shop” for obtaining all necessary permits through a single application process for major infrastructure projects.

- Centralized data collection and a comprehensive online database with GIS maps should be established to improve project tracking.

- Better regional planning and environmental preassessment to allow authorities to gather information in advance and share it with potential developers.

- Recognizing the national interest and providing agencies with sufficient resources and training are important to give voice to the public interest and to ensure efficient and timely processing of permit applications and environmental reviews.

- In cases where local opposition or resources conflicts create controversy, independent mediators could facilitate fair resolutions.

- An ongoing formal review mechanism to identify and address regulatory barriers.

In the century ahead, America’s prospects will depend on the quality of its infrastructure, which in turn will depend on the efficiency of its permitting regime. Permitting reform is vital to America’s future and is becoming more urgent with each passing day.

Introduction

Around the world, uncertainties in the permitting process impose enormous costs on society.

Modern infrastructure is part of the foundation of an affluent society. From gleaming skyscrapers and rapid transportation to efficient energy and innovative communications networks, society is built on infrastructure. Yet even in the developed world, there is an infrastructure deficit. One recent study estimates a global infrastructure financing gap of $15 trillion by 2040.3 Underinvestment in infrastructure is a worldwide phenomenon, with many causes. In the developed world, one of the key causes is inefficient “permitting,” which refers to the process by which governments authorize the construction and operation of infrastructure. Major infrastructure projects such as offshore wind farms, liquefied natural gas (LNG) export facilities, and utility-scale solar plants invariably require multiple permits from national and/or local governments, and in virtually all major industrial economies those permits entail lengthy assessment of environmental impacts.

The EIA process often takes more time than actual construction, and sometimes is even more expensive. The costs, delays, and uncertainties of the process are a major hurdle to the efficient deployment of needed infrastructure.

In most of the developed world, the permitting process is characterized by significant paperwork burdens, delays, and uncertainties, and imposes significant burdens on government resources. The resulting inefficiency in permitting deprives society of many needed infrastructure projects that would otherwise show a positive return on investment. Hence, inefficient permitting imposes enormous costs on society, costs which are difficult to quantify and not fully understood by investors or policymakers.

In the United States, a bipartisan consensus on the need to reform the federal system of permitting and environmental review for major infrastructure projects has been slowly building for more than a decade. The realization is gaining ground that the burdens, delays, and uncertainties of the federal permitting process are a daunting obstacle to infrastructure modernization, including any clean energy transition, and a significant global disadvantage for the country as a whole. This realization led, most recently, to Congress enacting significant permitting reforms as part of the recent Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, which raised America’s statutory debt ceiling.4

But those reforms, while significant, are not enough. Much more sweeping reform is needed. As one McKinsey report noted, “Large infrastructure projects suffer from significant undermanagement of risk throughout the life cycle of a project, as the management of risk isn’t properly accounted for in their planning.”5 This is nowhere truer than in the United States.

This report aims to fill a number of gaps in our understanding of those obstacles. It surveys infrastructure permitting regimes of select industrial economies to glean best practices in reducing burdens, delays, and uncertainties. The report sheds light on the many significant and often poorly understood costs that the permitting process imposes on infrastructure investments, public and private.

Beyond the obvious – the costs of the permit application to the developer, the costs to the government of processing the permit application, the cost of lawsuits brought to stop the projects – there is the cost that potential delays impose on the initial investment decision. The potential for delay is often a “pure uncertainty” (as opposed to a statistically quantifiable risk) that constrains the supply of infrastructure and results in higher prices than would be obtained under conditions of efficient infrastructure delivery.6

Accordingly, this report begins with a discussion of the economic impact of permitting risk and uncertainty. It then looks at the daunting obstacles that permitting costs pose for the deployment of clean energy infrastructure at the scale and speed necessary to achieve the “Net Zero” emissions reductions targets of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. The report then argues that efficient permitting is a vital competitive advantage for an industrial economy and will be a major determinant of economic leadership in the century ahead.

Next, the report surveys the permitting and environmental review regimes of major economies around the world: the United States, the European Union (including Germany, Denmark, Spain, the Netherlands, and Norway), Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and China. Particular attention focuses on recent reform efforts in those jurisdictions.

The report concludes with a summary of best practices from the around the world, including a discussion of what are likely to be the world’s best-performing permitting regimes, and ending with recommendations for U.S. policymakers.

Further research is needed in all these areas. A systematic assessment of survey data is warranted, particularly longitudinal data that tracks projects from proposal to the early years of operation. While the scope of this report is necessarily qualitative, it will hopefully serve as a first step toward the more comprehensive examination that is needed.

The Economics of Permitting Risk

Permitting risks are not properly accounted for in infrastructure investments, planning, or policy.

Understanding the risks associated with infrastructure investments is essential for getting infrastructure policy right. Yet despite its strategic importance, the scale of capital at stake, and lots of lessons from the “school of hard knocks,” those risks remain poorly understood. There is a growing recognition among international organizations, governments, investors, and infrastructure operators about the need to account for, and mitigate, risks in infrastructure projects.

Infrastructure investment involves complex risk analysis, allocation, and mitigation due to the unique and illiquid nature of such investments. Investors must carefully analyze the risks associated with a project throughout its lifespan and determine what premium to charge for bearing those risks, as well as decide whether the risk is tolerable at any price. Where private financing perceives prohibitive risks, or the scale of capital is beyond the capacity of a country’s private sector, governments need to step in, often partnering with the private sector and, among other things, absorbing some of the private-side risk.

Infrastructure Investment: Cost, Risk, and Uncertainty

Infrastructure investments entail a wide variety of costs, including the risk of loss. Among the costs of the development process are the following:

- Developer Permit Costs. These include both the cost of the permit application and the opportunity cost of the time spent complying with permitting requirements and represent largely irreversible investments.

- Developer Construction Costs. These are the costs of physical construction after securing the permit, which may entail expenditures prior to securing the permit. Aside from capital assets, which may be saleable or stranded, these may also be largely irreversible investments.

- Regulator Process Cost. This is the cost to government authorities of processing all needed approvals.

- Litigation Costs. These are the costs to developers and government authorities associated with litigation related to the permitting process and initial operational launch of the project.

- Uncertainty. This is the potential loss associated with cost overruns, delay, or abandonment of the project, and less-than-expected revenues once operational. Economists distinguish between quantifiable risks and unquantifiable uncertainties.

Beyond the expected costs of development, investors face significant risks that add to the “cost” of investment. Those risks consist of a range of possible losses from negligible to total loss, with associated probabilities from unlikely to virtually certain. Because the costs of development accumulate throughout the development process, the risks change over time, continuously impacting management and investment decisions. Government incentives can mitigate exposure to risk, reduce potential losses, and increase prospective returns, thereby making infrastructure investments more viable. But that often means exchanging one form of political and regulatory risk for another, as the investments then become dependent on subsidies the continuance of which depends on political factors entirely beyond investors’ control.

As one McKinsey report notes, “Large infrastructure projects suffer from significant undermanagement of risk in practically all stages of the value chain and throughout the life cycle of a project.”7 As the McKinsey report notes, the development of modern infrastructure projects is highly complex, involving a wide range of risks. Investors often have assumptions about the regulatory framework and viability of the permit application that are largely speculative. Government officials often overlook how the risks of the permitting process impact investors’ decisions, even when they care. All too often they don’t, particularly in the case of agencies captured by environmental advocacy groups that are opposed to industrial development generally.

As a result, the cost of financing infrastructure rises, often beyond the point where debt financing is viable, forcing disproportionate reliance on equity and public sources of financing.8 The reduced supply of efficient infrastructure investments results in a reduced supply of infrastructure, raising prices across the economy and resulting in significant social losses, including deadweight loss.

These losses ripple across the economy, reducing economic output and weakening the country’s economic prospects. They are all part of the cost of inefficient permitting.

Towards a Taxonomy of Permitting Risk

The Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) report Infrastructure Financing: Instruments and Investments, grouped dozens of risk factors into three categories: (1) political and regulatory risk, (2) macroeconomic and business risk, and (3) technical risk.9 These risks all affect the “time-value of money,” and therefore impact the real cost of capital. Prominent among political and regulatory risks are environmental review, rise in pre-construction costs from a longer-than expected permitting process, and cancellation of permits.10 These permitting risks resist quantification for several reasons. Longitudinal data that track individual projects from proposal through completion or abandonment are hard to find and aggregate. Moreover, permitting regimes vary so much from country to country that a transnational apples-to-apples comparison is difficult even when one can get the data. This contrasts with other kinds of regulatory risk, such as changes in taxation, regulation, or legal environment, and with macroeconomic risks such as inflation and exchange rate fluctuations, about which information is more readily available.

The impact of this gap in our understanding of infrastructure risks is hard to overstate. It reduces many investment decisions to guesswork, ultimately resulting in misallocation of resources and dead-weight social loss. To give one prominent example, Princeton University’s Net Zero America report (Princeton Net Zero Study) estimates that the U.S. will have to invest as much as $14 trillion to achieve net-zero by 2050.11 But that estimated capital cost is subject to a major caveat, buried in a footnote on page 254 of the report:

*Estimated capital cost of energy supply assets including power generation, transmission and distribution, fuels conversion assets and CO2 transport infrastructure. Excludes liquid and gaseous fuel distribution infrastructure for which very significant investments will be needed across all net zero pathways. Also excludes pre-investment studies, permitting and finance costs.

That is quite an asterisk, containing two major sources of highly variable cost for a renewable energy transition. First is the quiet reference to the enormous amount of new dispatchable fossil fuel power that will be required to keep the electricity grid stable as renewables are added.12 Second, and central to this report, is the exclusion of “pre-investment studies, permitting and finance costs” from the estimate of transition costs.

Permitting represents a crucial variable cost in infrastructure investments. In the United States alone, the full extent of such costs is almost certainly in the hundreds of billions of dollars and could be in the trillions. Any complete estimate of permitting costs must include not just the cost of compliance with the permitting process but also the impact of permitting uncertainty. That uncertainty is a combination of potential loss and probabilities that are mostly unknown, because the relevant sectoral data are woefully lacking.

Whatever the extent of the economic losses from inefficient permitting, those losses are clearly significant. One influential academic study notes that inefficient permitting and resulting delays lead to increased costs and postponement of project benefits, hinder construction schedules, and create opportunities for political interference.13 Inefficiency entails unnecessary costs incurred because of delay or duplication of effort: extra process costs to achieve the same outcome. Inefficiencies have negative consequences for the permitting agency, the project developer, and the public. These problems, the authors note, are particularly prevalent in innovative and environmentally beneficial projects. Despite the importance of permitting in environmental regulation, there has been limited research on the factors influencing the effectiveness of these processes.

Of the risks of permitting, the least well-understood almost certainly entails the greatest cost: the uncertainty associated with how long the permitting process will take. Because the delay can range from minor to long enough that the project has to be abandoned, the risk of delay comprehends a non-trivial possibility of total loss of the capital invested, particularly prior to commencement of construction. The pre-construction permitting process often lasts longer than actual construction, sometimes much longer. In the typical infrastructure project, years are spent navigating the permitting process before any capital assets have been acquired.

Virtually all the funds expended in the permitting process prior to the acquisition of capital assets needed for construction represent an “irreversible investment”: Once made, the investment generally cannot be recovered if the permitting process is unsuccessful.15 And there is usually little way to estimate the chances of significant delay or denial of the permit application.16 That is due, as previously noted, to lack of data about similar projects, but it also due to the indeterminacy of the legal regime, which endows regulators with an arbitrary degree of authority, making their decisions and the whole course of interaction highly unpredictable.

These costs can rise exponentially with infrastructure scale. The largest infrastructure projects are typically extraordinary feats of engineering. Such projects—for example, large offshore wind installations—typically entail construction supply chains of staggering complexity. The various phases of the project must be sequenced efficiently, and if permitting delays throw off the sequence, construction costs can quickly balloon alongside lost revenue to the point of catastrophic losses.

The Economics of Uncertainty

To understand the costs which arise from the potential for delayed operations, start with a typical interruption in business activity. Business interruption insurance typically covers both lost profits and fixed costs during the interruption period.17 To put this in economics terms, business interruption insurance does not cover “direct costs” of production, which can be avoided by not producing. It does cover “indirect costs” of production, such as rent, taxes, and some employee salaries, which cannot be avoided by temporarily reducing production and would therefore represent an economic loss to the business. To recover the full opportunity cost of the owner’s capital and labor, such insurance typically also covers lost profits that could reasonably be anticipated.

Now suppose an insurer decides to enter the infrastructure-permitting-risk-insurance business. He offers to insure the developer of a utility-scale solar plant to be built on federal land in Arizona against the potential loss resulting from a delayed or denied permit from the Bureau of Land Management. The developer wants the insurer to cover the irreversible investments made during the permit application

(i.e., the $25 million it might cost to develop the permit application, most of which cannot be recouped). To fully recoup his opportunity costs, the developer also wants the insurance to cover some of the expected profits.

How would the insurer price that policy? Insurance premiums are based on actuarial science applied to a sufficiently large and reliable data set so that the insurer can know with some precision and confidence the probability that any particular insured will file a claim. The more limited the data set that the prospective insured belongs to, the more uninsurable is the person or project. In the real world, infrastructure projects in development are largely uninsurable for business interruption, for the same reason that debt financing is generally unavailable to such investments: the unknowns of the regulatory process are simply too great.

In the face of such uncertainties, the irreversible investment of a permit application is often a grim prospect, testing even the most risk-tolerant investors.18 In his 1921 treatise on economic theory, Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit, University of Chicago economist Frank Knight wrote, “There is a fundamental distinction between the reward for taking a known risk and that for assuming a risk whose value itself is not known.”19 A known risk, he wrote, is “easily converted into an effective certainty by grouping cases,” whereupon it becomes insurable, while the “higher form of uncertainty not susceptible to measurement” is uninsurable.

Knight found the possibility for pure profit in that “higher form of uncertainty,” advancing a pragmatic approach to innovation that relied heavily on entrepreneurial agency. Of course, pure uncertainty can be a source of profit as long as the outcome depends on the entrepreneur’s efforts. If the prospects for an investment are both dominated by uncertainty and mostly outside the investor’s control, then the enterprise is more speculative than entrepreneurial, more roulette than poker, as it were.

One excellent International Monetary Fund (IMF) Working Paper asks, “What are the main underlying factors that determine the level of insurance coverage across countries?” In answering the question, the authors make a crucial connection among Knightian uncertainty, the strength of a country’s institutions, and the insurability of people in that country:

When institutional quality is lower, uncertainty is higher and insurability is lower; at the same time, income levels tend to be lower. … [T]he institutional quality-transparency-uncertainty nexus is the dominant determinant of insurability. In general, weak governance results in uninsurable risks; at least, it tends to make risks more difficult to quantify, which results in lower insurability. Using Knight’s argument, “the structures and methods for reducing uncertainty” are not as developed and are undermined by weak governance in countries where insurance coverage is low.20

The lack of comprehensive longitudinal data on project-level permit application outcomes is a major impediment both to infrastructure delivery and to infrastructure policy. The U.S. government should prioritize the collection of this data, for projects in the U.S. as well as abroad.

Net Zero Goals Face Overwhelming Permitting Obstacles

Permitting risk is a major obstacle to clean energy.

Most of the world’s countries committed to reducing carbon emissions to “net zero” by 2050 in accordance with the goal of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, which is to keep global temperature rise under 1.5 degrees Celsius.21 Accomplishing this goal would entail replacing or offsetting nearly 90 percent of the world’s current energy sources with a mix of solar, wind, nuclear, and other advanced technologies.22 Questions about whether the Paris Agreement’s net-zero targets are sensible in the first place cannot be readily dismissed. Every policy must be assessed through the lens of cost-benefit analysis, and both the costs and benefits of a net-zero transition continue to elude reliable quantification. The costs could turn out to be far greater than current estimates, and there are compelling reasons to doubt that the benefits could ever be measured, or attributed with confidence to the policy if they could be measured.

That debate is beyond the scope of this report, which focuses instead on a different problem. Even if the net-zero targets of the Paris Agreement were advisable, they simply are not achievable under current law. That is because the process for environmental review and authorization of energy infrastructure in the major industrial economies is too burdensome, moves too slowly, imposes too much uncertainty on private investment decisions, and requires such an inordinate investment of government time and resources that total amount of renewable energy capacity that can realistically be authorized is highly constrained, and falls far short of what the major studies suggest would be needed to achieve net-zero.

Many prominent studies have laid out optimistic pathways for achieving net-zero. They generally estimate what the transition would cost, but none of them grapple with the impact that permitting risk has on capital formation for a clean energy transition. As mentioned earlier in this report, the Princeton Net Zero Study explains in a footnote that its estimates do not account for permitting costs at all. The prominent McKinsey report, The Net-Zero Transition: What It Would Cost, What It Could Bring, mentions the word “permitting” once in 224 pages, listing “land constraints for permitting renewables” as among the “short-term risks and challenges” of a net-zero transition in the electrical power sector.23

This section shows how permitting poses insuperable obstacles for any net-zero transition, both for the world and for America in particular.

The Difficult Path to Global Net Zero

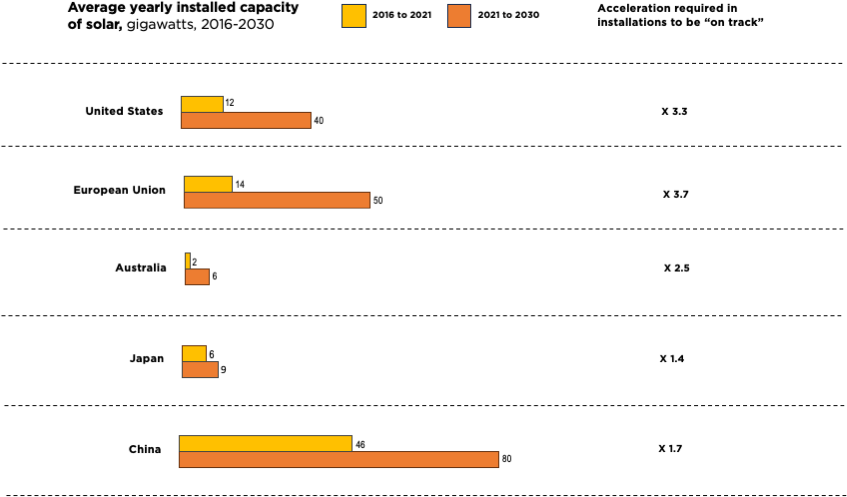

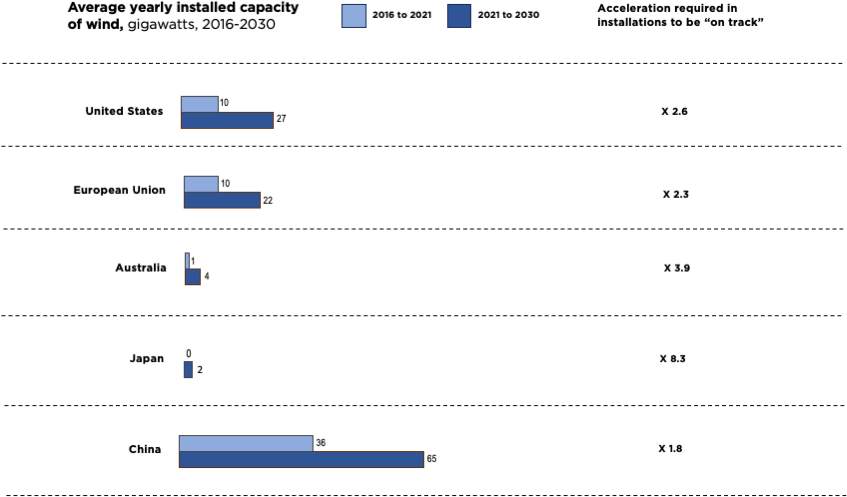

McKinsey estimates that net-zero will require an additional $3.5 trillion in average annual capital investment globally through 2050.24 It estimates that an additional $100 trillion would be required to address the gap between the “current trajectory” and the trajectory of an “achieved commitments” scenario. In the renewable energy sector, McKinsey estimates that annual solar and wind installed capacity would need to nearly triple, from approximately 180 gigawatts (GW) of average yearly installed capacity in 2016–21 to more than 520 GW over the coming decade, with different accelerations required across global regions.25

In the chart below, McKinsey estimates the multiple by which the pace of solar and wind installations would have to increase in order to achieve net-zero commitments in various countries.

To the extent different countries and regions are “lagging” in infrastructure development, there are, to be sure, different factors at play. In the developing world, the overriding constraint on the capacity to deliver infrastructure is almost certainly a basic lack of capital: They are poor countries. But in the developed world, the constraint of inefficient permitting looms large.

It is important to understand that inefficient permitting is not merely a constraint on the investors’ ability to deliver infrastructure, but also on the government’s ability to authorize it. In the United States, the current pace of permitting for renewables is almost certainly close to federal and state agencies’ maximum capacity for processing permit applications. Even with the massive subsidies in the Inflation Reduction Act,26 it is likely the case that without a doubling or tripling of the federal bureaucracy engaged in permit applications and National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) reviews—a workforce that is currently in the thousands—it will be impossible to significantly increase the pace of permitting under current law.

The Difficult Path to Net Zero America

In the United States, as in the rest of the world, a transition to net-zero or even a substantially decarbonized electricity would require a staggering amount of new clean energy infrastructure. The U.S. currently has about 1.14 terawatts (TW) of electrical generating capacity.27 In 2022, about 60 percent of U.S. total electricity generation was from coal and natural gas, another 18 percent from nuclear, and most of the remainder from renewable sources: 10 percent from wind, six percent from hydropower, and three percent from solar.28

Moreover, a clean energy transition would require not just replacing the 60 percent of fossil fuel generating capacity with renewable sources, but also accommodating future demand growth entirely through renewables, including enormous additional capacity to accommodate electric vehicles.

There are many estimates of the power capacity additions that would be required for a net-zero power sector, most of which are in the same general ballpark. For example, the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) estimates that to achieve a zero-carbon electrical system by 2035, the grid would need to add 900 gigawatts (GW) of new wind and solar, 80 GW of new nuclear capacity (doubling current nuclear capacity nationwide), and 280 GW of hydrogen-fueled turbines,29 a technology that has not been deployed anywhere at utility scale.

Many estimates do not even consider nuclear, largely because powerful environmental advocacy groups remain adamantly opposed to it. That may also explain why Congress has put virtually no effort into advancing nuclear power. The disregard for nuclear is a major obstacle to the clean energy transition, because most scenarios aim to replace the dispatchable baseload generation of coal and natural gas plants with intermittent wind and solar, creating significant challenges for reliability and capacity. Utility-scale batteries, smart grids, and similar technologies have come a long way, but the challenge of intermittency is why the International Energy Agency has called for a doubling and even tripling of nuclear power around the world for any chance of meeting the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting warming to no more than 1.5 degrees Celsius.30

America’s nuclear generating capacity is dwindling and there are no plans to build any new nuclear plants in the United States. But even if there were, they could not be part of the clean electricity mix in EPRI’s estimate. The permitting timeline for nuclear is the longest of any infrastructure sector. A pair of nuclear power reactors due to be operational by the end of 2024 in Georgia started their odyssey through the federal permitting process in 2006, after many years of project design and development.31 Nuclear regulatory reform is urgently needed, but Congress has done virtually nothing about it.

Of the studies about the pathway to net-zero in the United States, perhaps the most prominent and authoritative is that led by Princeton University, Net-Zero America.32 The study examines the required changes in various sectors, including energy, transportation, industry, and buildings, as well as the associated costs and benefits. According to the Princeton Net Zero Study, achieving net-zero by 2050 will require a complete or nearly complete phase-out of fossil fuels and an enormous deployment of new renewable energy infrastructure, along with sweeping transformations of the transportation, industrial, and building construction sectors.33

The Princeton study suggests that achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 is feasible, but it will require significant changes in various sectors, significant investments, and policy changes at all levels of government, including policies such as carbon pricing, clean energy standards, and regulations to support the deployment of renewable energy and energy-efficient technologies.34 The political hurdles facing any of those policies are daunting, but even if they could all be overcome it would not make a difference without sweeping reforms of the permitting system for infrastructure.

McKinsey estimates that the investments needed for a net-zero transition are underestimated because of “complicated siting and permitting that could, according to our research, delay projects by ten years or more.”35 Most estimates are far more sanguine, however. One notably optimistic review of 11 studies of non-nuclear pathways to clean electricity by 2030 and 2035, by Energy Innovation LLC, shows a consistent estimate across studies of about one terawatt of solar and wind, plus 100 GW of battery storage. That review notes that this would require an average annual deployment of new renewable energy capacity at double or triple the record rate of 31 GW of wind and solar additions in 2020, “a challenging but feasible pace of development.”36

The authors do not elaborate on why they think that would be “feasible,” perhaps because they have been spared the trials and tribulations of the NEPA process. But it is not remotely feasible. Since the early Obama administration, federal agencies have strained to streamline their permitting processes and increase throughput. They are virtually at the limit of the streamlining that current law will allow without leaving their permits and NEPA reviews vulnerable to court challenge.

Even if agencies’ permitting resources were doubled or tripled, there has been little recognition of the political challenge of doubling or tripling the level of local opposition to infrastructure development under a system that often seems tailor-made to empower small pockets of local opposition, to which the regional offices of federal agencies are very sensitive.

Local opposition arises from land-use impacts. To grasp the stupendous land-use requirements of a net-zero transition, consider just a few data points. McKinsey estimates that to achieve even a 50 percent reduction in CO2 emissions, 75 percent of all land in the U.S. with a strong renewable potential and proximity to transmission lines would need to be developed for either solar or onshore wind power.37 Deploying 500 GW of solar capacity would cover an area the size of New Jersey in solar panels. The number of new transmission-line miles required for net-zero is even more staggering: from 600,000 to one million miles of new high-voltage transmission lines, essentially doubling the number of miles in America’s current transmission network.38 And over every stream, across every plain, and around every mountain, there is the potential for fierce—and highly effective—opposition.

President Trump once called climate change “a hoax” and withdrew the United States from the Paris Agreement in 2018. (The United States officially rejoined the Paris Agreement in February 2021, a month into the Biden administration.) Senior officials in the Trump administration were generally either ambivalent to renewable energy, or openly hostile, and resisted subsidies. But simply by implementing minor reforms of the permitting process, and insisting on efficient permitting across agencies, the Trump administration rapidly increased the federal government’s rate of renewable energy permits. Meanwhile the rate of permitting has fallen under the Biden administration. Permitted capacity for renewable energy in the United States was 10 percent lower in 2022 than in 2020, the last year of President Trump’s administration.39 The lesson is clear: The major obstacles to net-zero are not a lack of political will to fight climate change, but simple bureaucratic inertia and conflicting priorities among those who are most committed to fighting climate change.

The Hard Lessons of Net Zero

The uncertainty surrounding permitting risk is just one of the many obstacles facing net-zero. Perhaps even more fatal to the hopes for net-zero is the generally accepted view among proponents of renewable energy that restricting the supply of fossil fuels will facilitate a clean energy transition. Paradoxically, for a variety of physical, economic, and political reasons, reducing the supply of fossil energy is far more likely to impede a transition to clean energy than to advance it.40 A study of those factors is beyond the scope of this report, but increasing attention has focused on this obstacle to net-zero, particularly outside the United States.41 As one McKinsey report notes, “Industry observers remark that the energy transition is already ‘disorderly.’ It will be made even more so if the imperatives of energy resilience and affordability are not addressed in parallel to bringing about the net-zero transition.”42

In fact, dangerous grid reliability issues are appearing with greater frequency in the United States, a major sign of a “disorderly transition.” Rolling blackouts in California in 2020, and a near repeat in 2022, and the power outages of the Texas ice storm in 2021, were all the result of too much renewable capacity pushed onto the grid without enough resilient dispatchable generation (from nuclear, natural gas, or coal) to back it up. As the McKinsey report notes:

Most capacity markets allow some share of a renewable plant’s power to count as firm power that could be called on when the system is in need. However, the intermittence of renewables introduces unreliability to the objective of delivering firming capacity at every moment in time. In most capacity markets, renewables’ stated flexibility could be adjusted to reflect this reality. System operators could use a more conservative calculation to revise capacity credits for intermittent renewables and other resources—basing projections on forecasts of future resource availability in addition to taking a more stringent view of what constitutes reliable output based on historical performance.43

The “adjustment” that McKinsey calls for would mean further reducing the generation capacity factor of renewable power plants, already heavily discounted compared with their nameplate capacity. The upshot would be an upward revision of the overall grid capacity needed to keep up with demand, facing utilities with a choice between rushing to add large amounts of renewable capacity they won’t need most of the time, just to make sure they can cover peak demand, or rushing to add dispatchable power generation, which in the short term means either coal or natural gas.

Despite the remarkable blind-spot for permitting risks in the most prominent studies of pathways to net-zero, it is finally dawning on key stakeholders around the world, and particularly in Europe, that a net-zero transition is simply impossible without sweeping reforms of permitting and environmental review processes.

The Competitive Advantage of Efficient Permitting

National prosperity depends on efficient regulation.

In the Harvard Business Review article “The Competitive Advantage of Nations,” Michael Porter argued that nations create wealth the same way companies do, by innovating.

National prosperity is created, not inherited. It does not grow out of a country’s natural endowments, its labor pool, its interest rates, or its currency’s value, as classical economics insists. A nation’s competitiveness depends on the capacity of its industry to innovate and upgrade.

… Ultimately, nations succeed in particular industries because their home environment is the most forward-looking, dynamic, and challenging.43 For a nation to keep innovating, and thereby maintain its competitive advantage, it must maintain, among other things, a favorable position “in factors of production, such as skilled labor or infrastructure, necessary to compete in a given industry.”44 To illustrate, consider the roughly 1.5 million jobs that have been added to America’s manufacturing sector since 2010,45 largely the result of lower electricity prices that resulted from the shale boom and consequent switch from coal to natural gas as the main source of American electricity: Per kilowatt-hour, U.S. commercial electricity is almost as cheap as in China ($0.15/kWh in the U.S. vs. $0.09/kWh in China), and just a small fraction of what it costs in Germany ($0.8/ kWh).46 With commercial electricity more than five times more expensive than in the U.S., it is a wonder that Germany maintains a competitive manufacturing industry. (Not surprisingly, BMW, which just a few decades ago manufactured exclusively in Germany, now manufactures vehicles in 15 different countries, with its largest production facility in Greer, South Carolina.)47

The shale boom was another in a long line of disruptive innovations by the American private sector, made possible by strong free-market competition under a stable and predictable rule of law. That combination has encouraged the risk-taking that is essential for innovation. Abundant natural resources, physical security, and a skilled labor force all played key roles. But a stable and predictable legal framework has proven indispensable, for without it the risks of private investment quickly become prohibitive. Then a society’s potential capital remains frozen, which is a major reason why poor countries remain poor.48

Complex economies like that of the United States sometimes exhibit aspects of both situations. At the retail level, that of automobile loans and driver’s licenses, the U.S. legal system protects everyday consumers efficiently and predictably. But the more heavily regulated the industry, and the more capital is at stake, the more unreliable and unpredictable the legal system becomes.

Despite the oft-repeated proposition that ever-more complex commercial arrangements require ever-more complex regulations, there are strong reasons to believe Prof. Richard Epstein’s observation that “simple rules work best in a complex world.”49 This is especially so when the added complexity results in ever-greater levels of discretion in the hands of regulators and officials, as is generally the case for infrastructure delivery in both developing and developed countries.

In their groundbreaking, Why Nations Fail, economists Darron Acemoglu and James Robinson distinguish between inclusive and extractive political institutions. Inclusive institutions are pluralistic and designed to benefit most people, while extractive ones “are designed to extract incomes and wealth from one subset of society to benefit a different subset.”50 They go on to observe, “Extractive political institutions concentrate power in the hands of a narrow elite and place few constraints on the exercise of this power.”51

In discussing “extractive institutions” Acemoglu and Robinson focus on developing countries, but their definition applies equally well to socialist systems, which aspire to redistribute wealth to achieve equal outcomes.52 As Friedrich Hayek observes, in socialist systems government officials charged with equalizing outcomes must be endowed with substantially arbitrary powers to mitigate the socially unequal or undesirable outcomes produced by a system of impartial justice.53 This has two major consequences for the private economy under socialism: First, “to produce the same result for different people, it is necessary to treat them differently.” To accomplish that the laws must be unequally applied, so the legal system itself tends to become indeterminate and unpredictable.54 Second, and relatedly, “the more the state ‘plans,’ the more difficult planning becomes for the individual.”55

Hence in a complex mixed economy like that of the United States, one should expect regulatory risk to rise exponentially with the scale of investment.56 Because regulatory risk is a major factor in cost-of-capital, one would expect such risk to be prohibitive in one or more sectors, depending on the regulatory climate in that sector. In such cases, government subsidies would be required to overcome the barrier to entry posed by regulatory and legal risk.57 The most common justification for the hundreds of billions of dollars that Congress has appropriated for renewable subsidies is that they are needed to make renewable sources cost-competitive with existing fossil-fuel sources. A more prosaic explanation is likelier: a major real reason renewables need subsidies is to compensate for the permitting risk that Congress has created.

Regulatory risk is highly variable from country to country, even among countries with otherwise similar economic characteristics. In the United States for example, a transportation project with any federal funding takes an average of seven years to complete the permit process, before construction can even begin.58 In Australia, by contrast, a country with similar per capita GDP, a complex highway-and-railway project like the Sydney Gateway motorway took two years to prepare and publish the required environmental and “master planning” documents and less than a year after that to obtain all necessary approvals.59 That is less than half the average approval time for a transportation project in the U.S. This gives Australia’s transportation sector, and its supply chain generally, an enormous competitive advantage. Although difficult to quantify, one would expect that competitive advantage to be reflected in greater job growth and greater wealth creation.

China is likely many decades from achieving the level of consumer protections available in the United States. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) exerts a stifling level of ownership and control over Chinese companies. But it may have a significant advantage over the United States in the delivery of infrastructure. This is because stifling ownership does not necessarily entail stifling regulatory risks or compliance costs. U.S. companies, though privately owned, are in many instances subject to heavier and more unpredictable regulations than are Chinese companies. One insidious advantage of the dictatorship of the CCP is that the decision to invest and the decision to authorize are ultimately made by the same entity. With the “investor” in substantial control of the outcome, “Knightian uncertainty” largely disappears as a check on infrastructure. Another is China’s capacity to pursue long-range strategic planning without the constraints of democratic governance. These are dangerous competitive advantages that constitutional democracies can overcome only by being more efficient and innovative.

Another kind of comparative advantage is relevant in the context of infrastructure regulation. Porter observes that the first country to anticipate a global regulatory trend puts its companies in a position to compete sooner.60 But as William Boulding and Markus Cristen observed in their 2001 Harvard Business Review article “First-Mover Disadvantage,” being first doesn’t always confer a competitive advantage.61 After examining hundreds of business units across multiple sectors, they found that “Pioneers in both consumer goods and industrial markets gained significant sales advantage, but they incurred even larger cost disadvantages.”62 The cost disadvantages arise from how much more difficult it is to modify an existing system through trial-and-error than to start from scratch informed by the mistakes of others.63 Something similar is readily observable in the realm of public policy. Regulatory program design is often beset by “first-mover disadvantage.” Indeed, the disadvantages are often worse because, for a variety of reasons, failing government programs are even more difficult to reform than failing business models.64

Survey of Permitting Regimes

Major economies are focused on permitting reform.

The world’s varied permitting systems have many features in common. In most of those in the present survey, projects are subject to regulation at multiple levels of government, and also by multiple agencies at the same level. So, for example, Australia, Germany, and the U.S. are all federal systems, with infrastructure projects subject to regulation at the national (federal) and subnational (state and local) levels. In such cases jurisdiction is usually concurrent, though local regulation is often preempted. Preemption of local regulatory obstacles can be a valuable feature of efficient permitting.

The European Union is similar in some respects to the United States, but there are notable differences. The EU’s top-level of regulatory authority—the European Commission—enacts regulations with the power to preempt contrary national or local laws, much as with federal preemption in the U.S. But it also has the power to impose horizontal harmonization of regulations on subordinate units of government, which federal regulators are formally barred from doing in the United States,65 although a variety of fiscal and regulatory tools under the head of “cooperative federalism” are often used to achieve similar results.66

The process for obtaining government authorization to build a major infrastructure project commonly depends upon an environmental impact analysis conducted by officials. In practice, the environmental impact analysis tends to be the “long pole in the tent” that determines that cost and overall timeframe for obtaining the needed authorization.

This section begins with the world’s first comprehensive framework for environmental impact analysis, the National Environmental Policy Act of the United States. In the years since its enactment in 1970, it has been widely imitated. And while it remains an international benchmark, it also shows signs of a “first-mover disadvantage” in regulatory design, achieving similar environmental benefits less efficiently than subsequent imitators. It then surveys a number of national systems within the European Union, and their interaction with the increasingly comprehensive EU regulatory framework. The section then looks at Australia and New Zealand, and goes on to examine infrastructure delivery governance in Japan and China.

Most of the governments in this survey have remained committed in principle to achieving net-zero under the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. As the enormous permitting obstacles to any net-zero transition have become harder to ignore, many jurisdictions have enacted reforms meant to increase speed and efficiency of permitting. Many such reforms have come in recent years and more are being negotiated and enacted even as this report goes to press. This report summarizes the latest of these efforts and concludes with a look at diplomatic efforts to advance permitting reform on a broad international basis, including at the recent 2023 G7 summit in Hiroshima, Japan.67

Permitting In the United States

Legal Framework

In the United States, the regulation of infrastructure deployment occurs under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).68 Passed in 1970, NEPA established the world’s first comprehensive framework for environmental impact analysis of major infrastructure projects. It has been widely imitated around the world and set the benchmark for environmental impact analysis.

Weeks before the publication of this report, key provisions of the law were amended, as part of the Fiscal Responsibility Act.69 Those changes are summarized at the end of this section.

NEPA requires federal agencies to evaluate the significant environmental impacts of “major federal actions,” which include activities agencies conduct directly, activities funded by agencies, and activities authorized by agencies where the law requires such authorization. Any such impacts need to be evaluated in an environmental impact statement (EIS) prepared by “the responsible official.”70 Projects as varied as federal forest management plans, highways funded partly with federal dollars, and utility-scale solar plants on federally managed land would all trigger the requirement for an EIS.

The EIS is the largest scope study of environmental impacts under NEPA. A typical EIS takes on average 4.5 years to prepare, consumes tens of thousands of agency person-hours, and costs millions of dollars in taxpayer resources—on top of the tens of millions an EIS and related permit application can cost project proponents.71

NEPA establishes three levels of review for evaluating these impacts. Small and routine agency actions – such as the acquisition of office supplies by a federal agency – may be excluded from EIS requirements by a “categorical exclusion.” For projects that are not excluded from review, but whose impacts may not trigger the significance threshold for an EIS, an Environmental Assessment (EA) 72 may be used to preliminarily evaluate the potential environmental impacts of the project. In practice, EAs are most often used to substantiate the lack of significant environmental impacts, which may be enshrined in a “Finding of No Significant Impact” (FONSI). The FONSI may be predicated on measures meant to mitigate environmental impacts of the agency action; this is often referred to as a “Mitigated FONSI.” When the proposed federal action is a “major action” and is likely to “significantly impact” the environment, the more extensive Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) is required.

Of note, NEPA applies to “major federal actions,” such as the decision to fund or authorize an infrastructure project, and not to the project itself.

This is an important distinction because where an EIS is required, NEPA requires that the agency study “alternatives.” Alternatives to the agency action may be quite different than alternatives to the project. For example, the alternative to the proposed issuance of a permit may be simply to deny the permit, whereas alternatives to the project itself are many. Unfortunately, agencies and courts often conflate the two, and therefore agencies spend inordinate amounts of time studying impacts of alternatives that the developer can readily exclude for business reasons, which is one source of the excessive paperwork and delays associated with NEPA.73

The application of NEPA to major infrastructure projects is usually triggered by an underlying “action statute” that requires one or more “action agencies” to take some action on a permit application. A myriad of laws can apply to a single infrastructure project. Examples include the Federal Land Policy and Management Act,74 Federal Power Act,75 Natural Gas Act,76 Clean Water Act,77 Endangered Species Act,78 and National Historic Preservation Act.79 Each of these laws can implicate one or more agencies. As a result, a single project can require permits from a dozen or more separate agencies, each operating under its own separate legal authorities.

The Federal Permitting Improvement Steering Council keeps an inventory of the permit requirements that can trigger application of NEPA.80 It is reproduced in full here, for both reference and dramatic effect:

There is no statutory framework for integrating these processes, which largely operate independently of each other. This is true even when federal law requires extensive interagency coordination, as with Section 7 consultation under the Endangered Species Act.

The interagency NEPA process is conducted loosely under a series of presidential orders that have been issued by the White House Council on Environmental Quality in the guise of “regulations” (CEQ NEPA Regulations).81 In the case of multiagency NEPA review, the Regulations provide for a “lead agency” and one or more “cooperating agencies” who team up to prepare a single EIS for their several agency “actions,” with the lead agency traditionally taking on the main effort of preparing the EIS. Infrastructure project permit applications almost invariably trigger multiple permit requirements from multiple agencies. Hence there is almost always a “lead agency” for a major infrastructure project.

The NEPA process is often a Homeric odyssey of trials and tribulations for project developers, but like the voyage of Odysseus it follows a certain general sequence. Once the agency determines that an EIS is necessary, it publishes a “notice of intent” (NOI) to prepare an EIS in the Federal Register. At this point the “scoping”

process begins. This process involves extensive opportunity for public input, for the purpose of bringing potential environmental impacts to light. The agency also begins to develop a range of alternatives to the proposed agency action, and prepares a comparison of impacts across alternatives, commonly including a “no action” alternative. Beneficial impacts are supposed to be included, but the study typically consists mainly of negative impacts, including, for example, impacts to protected species and habitat, impacts to protected wetlands, “viewshed” impacts, modification of land use under federal land use planning, and impacts to cultural heritage sites.

The public scoping process lends itself to controversy, and often the issues raised lead eventually to litigation, creating significant barriers at the “front end” and “back end.”82 Linear projects such as pipelines and transmission lines are particularly prone to such problems, as they create new opportunities for local opposition, and additional permitting requirements, along their entire length. Renewable energy projects such as wind and solar also tend to be controversial because of their impact on natural habitat.83 That impact is particularly pronounced given the significantly greater amount of land required per unit of renewable electrical capacity compared with natural gas and nuclear.84

After scoping, the lead agency proceeds to prepare a draft EIS, which analyzes the potential impacts of the proposed project and of the alternatives before the agency. There is a public review and comment period, during which interested parties can provide feedback on the Draft EIS (DEIS). The agency then prepares the Final EIS (FEIS), which takes into account the comments received during the public review period and identifies any changes to the project or its impacts. The FEIS is the agency record for the “Record of Decision” (ROD), which memorializes the agency’s decision on the permit application and specifies any monitoring and mitigation efforts. Under Sec. 706 of the Administrative Procedure Act, the sufficiency of the permit rests on the completeness of the agency record, in this case the FEIS.85 Hence any omission could lead to vacatur of the permit.

Throughout the NEPA process, the lead agency is required to consult with other agencies, as well as with the public and stakeholders, to ensure that potential environmental impacts are properly considered and addressed. State and local governments also have their own regulations and requirements for infrastructure projects. Unless preempted by federal law, a project will typically require construction and land-use permits under the ordinances of the local government. State laws may also require permits and those laws often trigger state-level environmental review procedures. Many state laws, most notably the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA),86 require environmental impact assessments and are generally patterned after NEPA.

Assessment of the American System

The U.S. system for federal permits and environmental reviews for major infrastructure projects is extraordinarily difficult, time-consuming, and uncertain for any project that is subject to the process. It also takes so much agency time and resources to process each permit application that the permitting process creates a significant bottleneck for infrastructure deployment at a national scale. The entire federal government produces at most 75 or 80 final EISs every year.87 Because the largest projects tend to require EISs, that pace is far short of what is needed to keep American infrastructure modern and reach any net-zero goal.

The risk associated with the costs, delays, and uncertainties of these processes lead many investors and developers to abandon projects or avoid them altogether, creating a need for massive public subsidies to overcome the risk barrier to investment. The federal and state processes for authorization and environmental review are often cited as the main barriers to renewable energy development.88

The risk of litigation is the main source of cost, delay, and uncertainty in the NEPA permitting process. Federal courts hold agencies to such high standards when applying NEPA that compliance is all but impossible to achieve with confidence.89

Agencies spend thousands of staff hours and millions in taxpayer resources trying to get every detail of an EIS right, but when challenged in court, only prevail in about 70 percent of cases. When they do not prevail, the permit and EIS upon which the permit rests are often vacated, and construction or operation of the project must be postponed.

The statutory purpose of NEPA is to inform agency decision makers. Yet, litigation risk compels agencies to conduct environmental reviews that are significantly more detailed than necessary or helpful to inform agency decision makers. There is no substantial performance standard for agencies that got nearly everything right. The omission of one paragraph that a court might like to have seen in a 1,000-page document could be deemed “arbitrary and capricious” under the Administrative Procedure Act.

Litigation is often driven by local opposition to projects. As a result, national policy priorities are routinely subordinated to small pockets of local opposition. Whether the goal is infrastructure modernization or net-zero, the U.S. system erects major barriers to the rapid deployment of infrastructure at scale.

Another major problem with the permitting process is the hydra-headed nature of agency permitting authorities. Efforts by multiple administrations to establish a coordinated process quickly run up against the reality of statutory structure, a problem that only Congress can fix. The CEQ Regulation’s provisions on a “lead agency” to prepare a single NEPA document in coordination with “cooperating agencies” does not relieve the project developer of having to create an interagency process from scratch among a bunch of agencies that often couldn’t care less what the developer has to say on any subject.

A related problem is that agencies take it on themselves to prepare environmental documents that the developer could prepare instead, much faster and just as well, subject to agency verification and approval. That is one of the most important changes in the 2020 Trump administration revisions to NEPA, which were partly pulled back by the Biden administration to placate environmental advocacy groups despite the fact that renewable energy companies were the disproportionate beneficiaries of the Trump-era reform.

A 2020 report by the White House CEQ found that the average time for completion of an EIS was 4.5 years, and the median time 3.5 years, with Final EISs running to 661 pages on average.90 Completion times varied significantly among agencies, however, with federally funded transportation projects taking an average of nearly seven years to complete the NEPA process.

Recent Developments

The major problems of the NEPA process arise from its statutory structure and that of related action statutes, as well as federal court interpretations of those statutes. Consequently, any major changes would have to come from Congress or the courts, where change occurs at a glacial pace if at all. In the United States, the federal executive branch is designed to act with much greater alacrity than the other two branches, but is confined to administrative powers, including implementing guidance and regulatory changes, within the structural “guard rails” defined by Congress and the courts. Hence the changes that come more easily tend to be more marginal.

The effort to streamline the NEPA process within the executive branch goes back at least to the administration of George W. Bush and is likely to continue in future administrations. Executive Order 13212 (2001) instructed agencies to “expedite their review of permits or take other actions necessary to accelerate the completion of” energy projects. This directive was expanded in the Energy Policy Act of 2005, which called for permitting improvements with respect to a wide variety of energy infrastructure categories.91

With renewable energy subsidies a major part of Congress’s response to the 2008 world financial crisis, federal agencies of the Obama era soon found themselves facing a bumper crop of renewable energy project applications. As it became clear that the new project applications would run into the same permitting bottleneck that had existed for years prior, the Obama administration began exploring ways to speed up the process. One result of these efforts was the 2012 “Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement for Solar Energy Development in Six Southwestern States” (2012 Solar PEIS) and the related “Approved Resource Management Plan Amendments/Record of Decision for Solar Energy Development in Six Southwestern States” (Solar PEIS Record of Decision).92

The six states—California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah and Colorado— were chosen because they contain the vast majority of the high-capacity-factor land for solar energy in the U.S., and because the great majority of that land is managed by a single agency, the Bureau of Land Management in the U.S. Department of Interior. Within that vast land area, the Solar PEIS Record of Decision identified 17 “Solar Energy Zones” designated as high-priority areas for utility-scale solar energy development; “variance areas” outside of SEZs where solar development could be approved under certain circumstances; “high potential resources conflict areas,” where solar development would pose a high potential conflict with natural, cultural, or visual resources; and 32 categories of land excluded from solar development.

The SEZs are generally “in the middle of nowhere” and far from the nearest transmission interconnection; consequently, SEZs have seen relatively few permit applications in the decade since. Most permit applications have been for development in “variance areas” nearer to existing or planned transmission routings; not surprisingly, these also tend to be nearer major population centers, where the cultural and other resource conflicts generate greatest local opposition. In Fiscal Year 2021, BLM approved 10 utility-scale solar projects totaling nearly 2.8 GW of nameplate capacity,93 which was more than 20 percent of the total solar capacity additions nationwide in 2021.94 BLM is currently considering a revision to the Solar PEIS which would add an additional five states of the Pacific Northwest to the program: Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, Washington, and Montana. BLM has asked for a significant increase in staff to keep pace with the increase in permit applications. Similar issues have faced other kinds of energy projects on federal land and offshore, from wind projects to fossil energy leasing programs.

In 2015, Congress created an expedited permitting procedure in the FAST Act.95 Title 41 of the Act (also known as “FAST-41”) requires agencies to post major infrastructure projects covered by the law on a public website (the Permitting Dashboard”)96 along with a “coordinated project plan” for all required agency authorizations and a timetable of milestones for the various permits to be issued (“permitting timetable”).97 The law creates the Federal Permitting Improvement Steering Council (FPISC), made up of senior officials from the main permitting agencies, supported by an executive director and a small staff. The Permitting Dashboard is supposed to be updated in real time, so the public can track progress on the permit applications and related NEPA review. The law also created certain limits on legal challenges, including a two-year statute of limitations.

Under President Trump, an array of deregulatory efforts was aimed at reducing environmental permitting requirements. The “One Federal Decision” policy aimed to streamline the environmental review and permitting process for major infrastructure projects.98 It required agencies to review and revise their permitting procedures as directed by the White House Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), which oversees implementation of NEPA, and required CEQ to review and if necessary, revise its NEPA Regulations.

On July 16, 2020, the Trump administration published a significant revision of the CEQ Regulation, the first time since 1978 that there has been a significant revision to the Regulation.99 The revision implemented pageand time-limits on the NEPA process, clarified key terms, made the process more inclusive of stakeholder views, and sought to make the process more predictable for agencies and project proponents. The changes were meant to benefit virtually all stakeholders, including taxpayers, agencies, project proponents, local residents, renewable energy producers, and environmental advocacy groups. However, resistance from vested interests has been significant, and the Biden administration has repealed many of the changes.100

The U.S. Congress has tended so far to see infrastructure challenges as a matter of inadequate funding rather than inadequate regulation. Since the start of the Biden administration in January 2021, two key fiscal initiatives have sought to accelerate infrastructure deployment, including clean infrastructure supporting a net-zero transition: The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) of 2021,101 which appropriated $1.2 trillion,102 and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022,103 which appropriated as much as another $1.2 trillion, according to Goldman Sachs.104

It is far from clear that the subsidies can be spent before they expire or are repealed. As of January 31, 2023, more than a year after passage of the IIJA, only about $43 billion of the $1.2 trillion has been awarded.105 The subsidies in the IRA, which consist mostly of income tax credits (ITCs) and production tax credits (PTCs), will materialize only when the projects are in service and generating revenue against which the credits can be claimed. No authoritative assessment has been made of what fraction of the potential aggregate total of ITCs can be permitted over time.

Several bills have been filed in Congress that would streamline different aspects of the NEPA process, but these have encountered obstacles that have thus far proven insurmountable. In the 117th Congress (the first two years of the Biden administration, during which Democrats controlled both the House of Representatives and Senate as well as the White House), the main effort at streamlining the permitting process was filed by Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV), the powerful chairman of the Energy and Natural Resources Committee.

As a side agreement to the IRA, Senator Manchin secured agreement from the Democrat leadership in the Senate to bring up a permitting reform package. The “Manchin bill”106 that ultimately emerged would have created largely voluntary time-limits for agency permitting processes and would have significantly amended the process for permitting linear projects such as natural gas pipelines and transmission lines that have faced persistent delays from state misuse of water-quality certification authority under Sec. 401 of the Clean Water Act. The bill would have provided for the designation of nationally important transmission projects and would have empowered the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to socialize project costs among consumers of electricity.

The bill had to be pulled when Republican leaders (who objected to the transmission-related provisions) and the Progressive Caucus (who objected to the natural gas pipeline provisions) combined in opposition to it, and it became clear that Senator Manchin didn’t have the votes to pass the measure.

Stakeholders interested in infrastructure development across the political spectrum, including proponents of both clean energy and fossil energy, continued to call for sweeping reforms to America’s system of permitting and environmental reviews.107 Their calls were finally heeded, at least in part, in the bipartisan agreement to raise the national debt ceiling.

Permitting Reforms in the Debt Ceiling Compromise

After several attempts to enact permitting reform, significant reforms were finally enacted on June 3, 2023, as part of the compromise to raise the “debt ceiling” of the U.S. government.108 The most significant of those changes is a set of amendments to NEPA itself— the first time in its history that NEPA has been significantly amended. The legislation also included congressional approval of the Mountain Valley Pipeline, a study on integration and cross-subsidization of electrical dispatch and transmission, and inclusion of energy storage among the sectors eligible for expedited permitting process under Title 41 of the FAST Act (“FAST-41”).

The inclusion of permitting reforms in the debt ceiling legislation is a significant step towards addressing the inefficient systems that have hindered infrastructure development in the United States. The amendments to the NEPA aim to streamline the process by focusing on the lead agency, establishing a reasonably foreseeable standard for impacts, and limiting the alternatives that must be considered. Empowering the lead agency, implementing time limits, and allowing project proponents to draft their own Environmental Impact Statements (EISs) further expedite the process. These reforms offer a promising framework for balancing environmental stewardship with the need for modern infrastructure.

Permitting in the European Union

In the European Union, national governments have their own laws providing for permits and environmental review procedures for infrastructure projects. Since 1985, there have been standards that harmonize national laws on environmental impact assessments (EIAs) particularly with respect to the categories of projects that require them, and minimum requirements for EIAs.

Across Europe, infrastructure development has been hampered by problems that would be familiar to American developers and agency officials: inordinate paperwork burdens, endless delays, and great uncertainty impacting capital formation.

In recent years, an increasing sense of urgency about climate change has led to an increasing consensus that renewable energy infrastructure needs to be delivered faster and at greater scale. This has led to major reforms by both the EU and national governments that have created accelerated procedures for renewable energy, particularly wind and solar. In reaction to the energy crisis that resulted from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its weaponization of energy supplies in response to EU sanctions, reforms have also provided for acceleration of natural gas pipelines and liquefied natural gas (LNG) import facilities, though these reforms have tended to be controversial.

As the following summaries make clear, these reforms are being enacted at an increasing pace as of the date of this report, making this area a rapidly moving target. Despite that rapidly moving target, however, and despite the heavy concentration of reform efforts in the renewable energy sector, many good ideas and “best practices” have come to light to overcome the problems associated with permitting.

Legal Framework