Law Enforcement for Rent

How Special Interests Fund Climate Policy through State Attorneys General

This paper is based on documents obtained over two and a half years from open records requests and, in some cases, subsequent litigation. Due to the volume of records, not all cited records are included in the body of this paper. Key documents are provided in the paper’s appendix, which can be accessed at CEI.org. The complete collection of documents cited in this paper is available at ClimateLitigationWatch.org, a project of the nonprofit public interest law firm Government Accountability & Oversight.

Executive Summary

This paper details an extensive and elaborate campaign using elective law enforcement offices, in coordination with major donors and activist pressure groups, to attain a policy agenda that failed through the democratic process. The plan is revealed in emails and other public records obtained during two and a half years of requests under state open records laws. Most are being released now for the first time. Many were obtained only by court order in the face of a determined and coordinated resistance that one deputy attorney general foresaw, expressing early concerns over “an affirmative obligation to always litigate” requests looking into the effort. The paper details how donor-financed governance has expanded into dangerous and likely unconstitutional territory: state attorney general (AG) offices.

The plan traces back to 2012 when activists agreed to seek “a single sympathetic attorney general” to assist their cause. AGs began subpoenaing private parties’ records in service of a campaign of litigation against opponents of their climate policy agenda. The public records date to a July 2015 email in which Peter Frumhoff of the Union of Concerned Scientists confided the group’s involvement with AGs.

Those public records reveal the following: (a) donors introduced plaintiffs’ lawyers to AG offices (OAGs), (b) a slideshow tour by plaintiffs’ lawyers recruiting OAGs to the effort, and (c) senior attorneys from OAGs flying in—some at taxpayer expense and others on the donors’ tab, which had been run through a pressure group— for a briefing with “prospective funders” about “potential state causes of action against major carbon producers.” One presenter described this briefing as a“secret meeting.”It was secret enough that one AG litigated to withhold the agenda— under implausible claims of privilege—for a year and a half before being compelled by a court to release the lineup for what turned out to have been an AG-assisted fundraiser.

Those public records reveal the anatomy of what began as an “informal coalition” of AGs to use the legal system in pursuit of an overtly political agenda in coordination with activists and plaintiffs’ lawyers. That coalition disbanded under open records and media scrutiny, but it has now reconstituted through a program by which donorsfund, privately hire, andplace investigators and prosecutors in AG offices. It uses a nonprofit organization to pass the funding through and to provide the OAGs with a network of “pro bono” attorneys and public relations services. In return, OAGs provide office space to the privately hired prosecutors; agree they are there to “advanc[e] progressive clean energy, climate change, and environmental legal positions”; and provide regular reports about their work.

Led and funded by former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, this scheme hires “Research Fellows,” which it then places as activist “Special Assistant Attorneys General.” All of the participating OAGs had to promise that this work would not get done but for this private funding. All OAGs also certified they are not violating the law by accepting privately funded prosecutors. At best, as several OAGs tacitly admit, this unprecedented arrangement operates in a gray area with neither prohibition nor authority. One state where the scheme is arguably illegal is New York, where disgraced former Attorney General Eric Schneiderman had a leading and organizing role at every stage of the campaign this paper describes.

The New York OAG openly boasted to a donor that its “need” for privately funded prosecutors was driven in part by the “significant strain on staff resources” that had been caused by its “non- litigation advocacy”—that described as its having “led” the resistance to the Trump administration. Importantly, the NYOAG also cited its campaign “building models for two different types of common law cases to seek compensation” from industries for supposedly having caused global warming; moreover, it “needs additional attorney resources to assist with this project.”On these bases and with a claim to having statutory authority to enter the unprecedented arrangement—a claim which on its face appears to be an invention—the NYOAG was awarded not one but two privately underwritten prosecutors.

This is the most dangerous example of a modus operandi we have found: it uses nonprofit organizations as pass-through entities by which donors can support elected officials to, in turn, use their offices to advance a specific set of policies favored by said donors. It also uses resources that legislatures will not provide and that donors cannot legally provide directly. The budget for climate policy work alone is in the tens of millions of dollars per year.

Across various levels of government—including mayors and governors—the bulk of this money is budgeted for pass-through nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and off-the-books consultants, report writers, and public relations (PR) firms that are hired through an NGO. The NGO takes a percentage as its fee (up to 24 percent in some cases). Another component involves privately hiring and then placing in-house, non- official personnel as advisors when they are actually employed by a donor’s group.

The extension of this billion-dollar per year climate industry to privately fund AG investigations sets a dangerous precedent. It represents private interests commandeering the state’s police powers to target opponents of their policy agenda and to hijack the justice system as a way to overturn the democratic process’s rejection of a political agenda.

As a subsequent report will affirm, this model of using nonprofit groups as cutouts for donors to finance elected officials’ activism is, in fact, widely adopted generally by the axis of donors, elected officials, and NGOs and by the climate litigation industry specifically. The de facto law enforcement for hire by private interests raises concerns beyond mere political opportunism, obvious appearances of impropriety, or even compliant 501(c)3s that seemingly rent out their tax-exempt status on behalf of activist donors.

The use of this approach by AGs carries legal, ethical, and constitutional implications, as well as for the integrity of law enforcement and the constitutional policy process. The public–private partnership of law enforcement for hire revealed in this report, in which the partnership uses public office to expend resources not appropriated or approved by their legislatures, raises significant constitutional and other legal issues—as well as ethics concerns—and should be the subject of prompt and serious legislative oversight.

Introduction

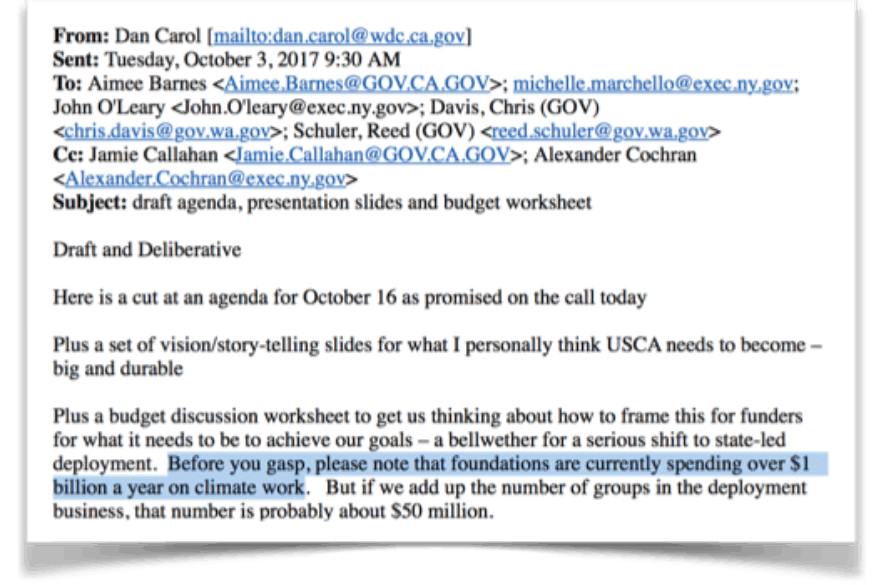

BEFORE YOU GASP, PLEASE NOTE that foundations are currently spending over $1 billion a year on climate work.”1 So wrote Dan Carol, a senior aide to California Governor Jerry Brown (D), on October 3, 2017, to his colleagues and staff members for New York Governor Andrew Cuomo (D) and Washington Governor Jay Inslee (D) regarding charitable foundation spending that promotes their climate policy agenda (see Figure 1). This figure dwarfs spending in opposition to that agenda—efforts to portray matters otherwise notwithstanding.2

Carol offered this sum to make his case that $50 million per year is reasonable to ask so donors can privately underwrite an off-the-books network of “support functions” for a handful of governors’ climate policy advocacy.

In further support of his position, Carol attached a “draft agenda, presentation slides, and budget worksheet.”Those items are among a large cache of public records that were obtained by the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI), along with other public policy groups, and that detail and propose the exploitation of a “plethora of funder interest” in secretly bankrolling the public office holders’ use of their positions to take a more aggressive role concerning climate politics and policy.

This years-long campaign by substantial, left-leaning donors revealed in Carol’s email correspondence and in other emails produced under state open records laws has now expanded into dangerous and likely unconstitutional territory. Led and funded by former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, this scheme centers

Figure 1

on paying to place activist attorneys—dubbed State Assistant Attorneys General (SAAGs)—in offices of the attorney general (OAGs) to play an agreed, predetermined, and activist role.

The intent is for those attorneys to advance the donors’ and large environmental advocacy groups’ “progressive clean energy, climate change, and environmental” policy agenda3 and—according to at least one OAG application—expressly to assist in pursuing the same agenda’s political opponents. In practice, this is a case of law enforcement for hire.

The roadmap for this campaign was laid out by activists and donors in 2012.4 Then in 2016, several state attorneys general (AGs) joined the campaign, which accelerated after that year’s elections. Public record requests looking into how such sensitive offices came to be used this way revealed that, since at least mid-2015, this use of law enforcement underwritten by private donors had secretly involved activist pressure groups, which are working in close coordination with donors and serving as the state AGs’ backroom strategists and partners.

After collapse of an early “informal coalition” of AGs—formed in the spring of 2016 to make desired climate policies become “reality”—in late 2017, another major donor, Bloomberg, announced his plan to use AG offices by privately funding the special AGs program. This expansion extends the model of off-the-books governance detailed by Carol and company from executive offices (such as mayors and governors) to AGs with law enforcement powers.

This approach represents an elaborate, deliberate plan to politicize state law enforcement offices in the service of an ideological, left-wing, climate policy agenda that has been frustrated by the democratic process. Under this scheme and deviating from standard government contracting procedures, private parties with an express policy advocacy agenda can pay to place activist investigators and lawyers in state AG offices to pursue that agenda.

Finally, as if to leave no doubt about the extent of this capture of law enforcement by activist donors, some of those chief law enforcement offices sent attorneys—some at taxpayer expense and others accepting payment of their travel expenses from a green advocacy group—to participate in a briefing on “Potential State Causes of Action against Major Carbon Producers” for prospective funders of the same environmentalist group.

Privately Funded Government and Investigations, an Overview

THE MODUS OPERANDI THAT WE have found entails using nonprofit organizations as pass-through entities by which donors support elected officials to use their offices to advance a specific set of policies favored by said donors, with resources that legislatures will not provide and which donors cannot legally provide directly. This model is being employed by activist elected prosecutors as part of this billion dollar-plus annual climate activism industry.

Across various levels of government— including mayors and governors—the bulk of the money apparently goes to pass-through nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and off-the-books consultants, report writers, and public relations firms hired through an NGO, which takes a percentage as its fee (up to 24 percent in some cases).5 Another component involves privately hiring and then placing in-house, non-official personnel as advisors when they are actually employed by a donor’s group—again as a cutout.

Extending this scheme to law enforcement seeds sympathetic state AG offices with additional lawyers to pursue“progressive clean energy, climate change, and environmental legal positions”—in other words, to use their offices to compensate for a political agenda’s failure through the political process.6 Even more troubling, this effort involves investigating opponents, of the climate policy agenda while using law enforcement to intimidate political opponents, seeking to silence the opposition.

The New York AG office’s successful application to the donors’ pass-through for two privately funded attorneys also shows that one objective is to provide personnel to its effort to extract financial settlements from those opponents. Recent practice suggests that the settlements will be distributed in part among political constituencies.

For its part, the group of donors offered inducements to entice AG offices to allow them to place attorneys and investigators in the law enforcement operation, including these:

- Supplemental donor-funded lawyers housed at the pass-through, a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization;

- An outside “pro bono” network of privately funded lawyers; and

- A public relations aide to serve those AGs; emails suggest that this approach also involves providing a media firm based in California to promote the AGs’ efforts.

This model of donors using non-profit groups as pass-throughs to make specific hires and to perform specific jobs, which now extends to the de facto contracting out of law enforcement to private interests, raises concerns beyond mere political opportunism, obvious appearances of impropriety, or even compliant 501(c)3s seemingly renting out their tax-exempt status on behalf of activist donors.7 The use of this approach by AGs carries legal, ethical, and constitutional implications for the integrity of law enforcement and the constitutional policy process. The scheme that gives rise to such concerns is the subject of this paper.

The Central Role of Eric Schneiderman

DISGRACED FORMER NEW YORK Attorney General Eric Schneiderman played a central—indeed the leading—DISGRACED FORMER NEW YORK

role among AGs in developing the schemes laid out in this paper. In fact, Schneiderman led the precursor “informal coalition”8 of state AGs who presented, along with former Vice President Al Gore, ata March 2016 pressconferencetopublicly launch what proved to be the first attempt at using AG offices to assist the climate litigation industry in going after “Exxon specifically, and the fossil fuel industry generally.”9 That effort also resulted in a subsequently withdrawn subpoena to CEI for 10 years’ worth of records going back 20 years.

Key facts and events in the development of the scheme follow:

- Emails obtained in open records litigation show the environmental pressure group Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) admitting, in July 2015, that it was working on OAG investigations of opponents of the climate agenda well before the AGs went public with their efforts in November of that year.

- In November 2015, months after this first admission of the collaboration, Schneiderman issued his first subpoena in pursuit of that agenda.

- Privilege logs filed by Schneiderman’s office in two Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) suits admit to withholding, as “law enforcement” materials, extensive correspondence regarding—in the AG office’s description— “company specific climate change information” with the office of environmentalist mega- donor Tom Steyer and Rockefeller Family Fund Director Lee Wasserman. This correspondence dated back at least nine months prior to Schneiderman’s issuing the first subpoena.10

- In March 2016, Schneiderman recruited a coalition of 16 Democratic state AGs to investigate opponents of their climate political agenda, under the name “Attorneys General United for Clean Power.”11 The coalition quickly dispersed a few months later when confronted with open records law requests and negative media attention.

- Schneiderman arranged for plaintiffs’ lawyer Matt Pawa and the Union of Concerned Scientists’ Peter Frumhoff to brief the AGs and Gore before their AGs United 2016 press conference—where the AGs announced their plans to pursue the investigations sought by UCS, plaintiffs’ lawyers, their partners, and their donors. Both Frumhoff and Pawa were involved early on in the campaign to find “a single sympathetic attorney general” to assist their cause by subpoenaing private parties’ records.

- Wendy Abrams, a major Democratic party and environmentalist group donor and recent member of UCS’ board of directors, provided Pawa entrée to at least one other law enforcement office. When arranging an April 2016 meeting for her and Pawa, as well as other attorneys who would figure prominently in the climate change litigation, to brief the office of Illinois AG Lisa Madigan, Abrams informed the office that she believed Pawa had brought the idea of the climate investigation to Schneiderman.12

- Schneiderman’s office provided UCS an invitation list of OAG contacts to participate in a briefing of outside parties on this collaborative climate litigation strategy, but specifically “Potential State Causes of Action” (discussing investigations and litigation the AGs might bring). The briefing included senior attorneys from AG offices in the Schneiderman-led coalition, UCS, plaintiffs’ lawyers, and their academic and activist partners.

- One presenter at the briefing described it to at least two correspondents as a“secret meeting.”

- There may be a good explanation for the secrecy. Recently obtained emails show that this “secret” briefing on litigation strategy, which Schneiderman’s office co-organized to ensure OAG attorneys flew in from around the country—some at taxpayer expense, others accepting UCS’s offer to pay their travel expenses—was, in fact, for “prospective funders.”

Several of the AG offices involved in this campaign have responded to requests for release of those public records by stonewalling, often forcing costly litigation. This litigation penalty has been paid for by nonprofit groups that the AGs have forced to sue to obtain public records. With two OAGs having been ordered to pay substantial costs and fees, this means an even greater price price has been paid by the taxpayers—not the climate activists’“prospective funders.”

Activist Government without Limits and Donor-Funded Law Enforcement

PUBLIC RECORDS CONFIRM THAT state AGs have willingly agreed to—and following very specific instructions have pleaded for—privately funded investigators and attorneys to use AG offices in pursuit of the “progressive clean energy, climate change, and environment” policy agenda.

This personnel benefit and other inducements were offered to the AGs through a program set up by former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, a billionaire donor who has ramped up his funding of climate policy activism in recent years. Bloomberg’s ideological campaign to impose specific policies includes openly vowing to run politically disfavored energy sources out of existence.13

Frustrated by failure through the democratic process, this campaign now includes the use of law enforcement for political ends. To attain his goals, Bloomberg established the State Energy and Environmental Impact Center at the New York University (NYU) School of Law, announcing that creation on August 15, 2017.14 The name itself is telling of his intent—to obtain his desired policy effects at the state level, after activists lost certain levers of power at the federal level.

Under the unusual arrangement offered by Bloomberg’s Center:

- A state attorney general’s office“hires” the NYU Impact Center as its attorney.

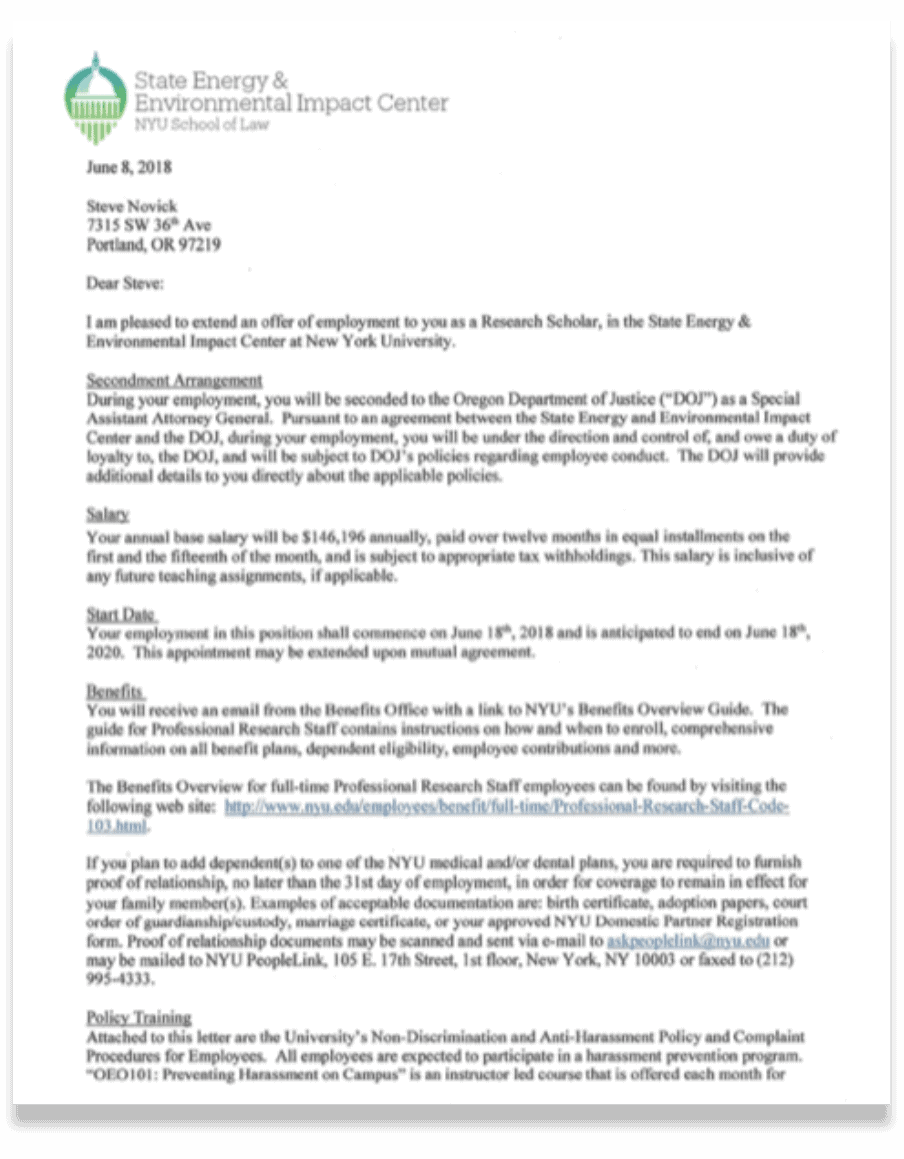

- The client pays nothing. Its consideration to NYU is in receiving the NYU Impact Center’s prosecutors (see Figure 2), who promise they will work on specified issues expressly of NYU’s interest and report back to NYU according to a specified schedule.15

- NYU also affords the AG ’s office a “pro bono” network of lawyers and a communications staffer who is dedicated to the work that the office agrees to perform.

- The contract is for an attorney–client (NYU– OAG) relationship.

Figure 2

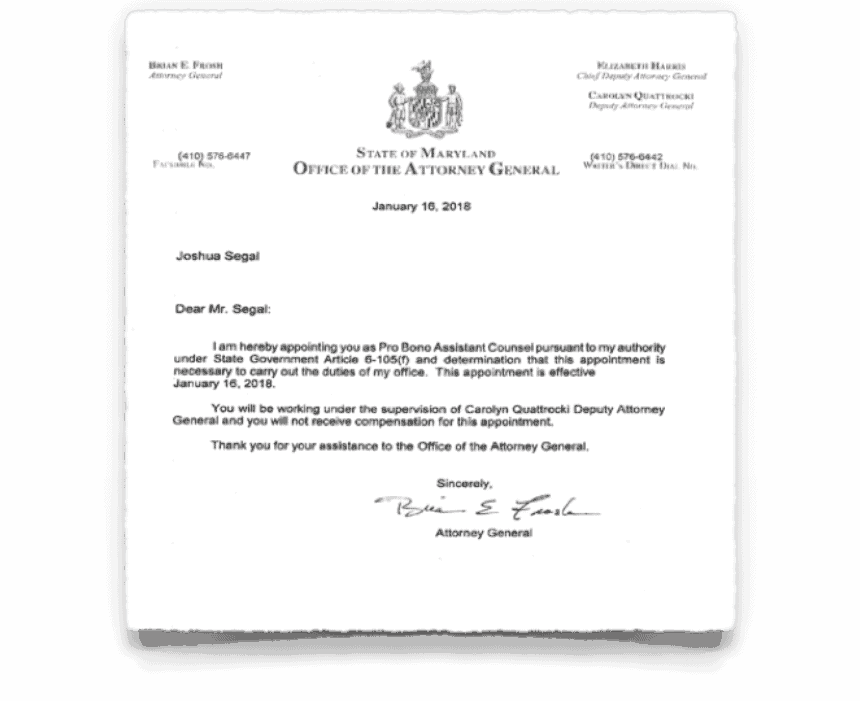

Figure 3

- NYU and the OAG sign a secondment agreement to place NYU’s attorneys in the OAG to work on specified matters (“progressive clean energy, climate change, and environmental legal positions”).16 OAG appoints the lawyer as e.g.“Pro bono Deputy Counsel”(see Figure 3).

- NYU pays the lawyer; so far those payments range between around $75,000 and $149,483 annually.

The first recruiting letter we have found, dated August 25, 2017, was sent by David Hayes, a former aide in the Clinton and Obama administrations and a green pressure group lawyer who now carries numerous affiliations. Hayes’s emails to the AG offices indicate thatboth he and NYU’s Center are affiliated at some level with the green group Resources for the Future, out of whose Washington, DC, office he indicated he runs this Bloomberg operation.17 However, neither group lists such a relationship on its website (last viewed July 29, 2018).

Hayes sent this pitch, to place privately hired and funded“Pro Bono Special Assistant Attorneys General,”to former campaign managers and other such political aides in politically sympathetic Democratic AG offices.

In that August 2017 letter, Hayes suggested that back-channel recruiting efforts were already well under way before the announcement: “We set a short deadline [September 15, 2017] at the request of several AGs who are anxious to get the process for placing NYU Fellows into AG offices as soon as possible.”18 Hayes expressed urgency to engage “the offices of certain state attorneys general” when he stated, “It’s in everyone’s interest that we work with the relevant AGs and hire these lawyers as soon as practicable.”19

The goals of the crowd seeking to capture this next level of authority for donor-advised governance are starkly illustrated in some surprisingly candid public comments. For instance, in an August 2017 Washington Post interview announcing the operation, Hayes let the most troubling aspect about this scheme out of the bag when he told the Washington Post: “[A]lthough ‘there’s never enough’ funding to support this sort of advocacy, the grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies could support not only litigation against the federal government but also enforcement activities on the state level.”20 [Emphases added.]

Elsewhere, Hayes boasted:

Those guys are the law enforcement folks. When it comes to climate change and clean energy, they are enforcing the law in the way that I think all of us in this room want them to— at least the progressive AGs. 21

Likely Democratic nominee for Attorney General of Florida Sean Shaw seems to reflect the mentality underlying this campaign when he describes the office to which he aspires:

It’s so free from interference. You can just sue and go after people. You don’t have to run it up any flagpole or get a committee or do anything.… You just do it.22

There are, inarguably, ethical and constitutional issues attendant to this element of that “$1 billion per year on climate work” beyond the obvious appearance of impropriety. The arrangement offers real potential for tainting all related investigations and litigation in the event that those problems become the subject of successful challenge. The workaround of running the funding of this activism through a nonprofit cutout may or may not prove enough to save the work from being thrown out as hopelessly tainted by bias.

The following is an analysis of the scheme and discussion of some of those legal and ethical concerns, with necessary background and citing source documents.

Background to the Bloomberg– AG Scheme and the “Climate– RICO” Gang

TO BEST UNDERSTAND WHAT COULD lead not only donors and lawyers but also elected AGs to consider engaging in such a scheme, it helps to first recall what the persistent use of state freedom of information laws in 2016–2017 helped expose. Also important is the meeting at which the AGs’ first campaign to assist the climate litigation industry was hatched several years prior.

The state AGs’ rationale for pursuing energy companies for “climate” settlements—and even for subpoenaing think tank records—has been something of a shape-shifter.23 Nonetheless, it arises from a 2012 conference in La Jolla, California,24 which was organized by a coalition of Rockefeller Foundation–supported groups.25 That conference produced a document that would serve as a blueprint for what has unfolded publicly over the past two and a half years.26 The blueprint notes: “State attorneys general can also subpoena documents, raising the possibility that a single sympathetic state attorney general might have substantial success in bringing key internal documents” out for the groups’ use.27

The activists were fortunate to find not one but several state AGs willing to join the campaign—at least until (apparently unanticipated) scrutiny and negative coverage began, which was prompted by open records requests into just how law enforcement offices came to be used in this way.28 In fact, the coordination exposed between green activists and a network of state AGs—in using the threat of racketeering and other investigations of the climate agenda’s political opponents— became a major topic of news coverage during 2016.

The AGs’ involvement began some time prior to July 2015 when the AGs’collaboration with activists makes its first appearance in emails obtained through public records litigation. In January 2016, various activists and these same plaintiffs’attorneys met at the offices of the Rockefeller Family Fund in New York to discuss the “[g]oals of an Exxon campaign,” which included to“delegitimize [it] as a political actor” and to“force officials to disassociate themselves from Exxon.” Critically, the agenda confessed to the goal of “getting discovery.” Also on the agenda: “Do we know which offices may already be considering action and how we can best engage to convince them to proceed?”29

Then, in March 2016, since-disgraced and now-former New York AG Eric Schneiderman and Vermont’s then-AG Bill Sorrell sought and briefly succeeded in forming (or in their word“renew[ing]”) an “informal coalition of Attorneys General” whose work on a broad spectrum of policy advocacy “has been an important part of the national effort to ensure adoption of stronger federal climate and energy policies.”30

This time the agenda entailed the political objectives of “ensuring that the promises made in Paris become reality”—referring to the December 2015 climate treaty—and to“expand the availability and usage of renewable energy.”31

It seems likely that the AGs’ initial foray into the activists’ requested involvement fell apart in some measure because of the (also apparently unexpected) aggressive pushback from one target of an AG subpoena—CEI.

With the benefit of hindsight, the AGs’ scattering under scrutiny and facing challenge is not surprising. Correspondence shows state government officials actively trying to hide their coordination through a purported “Common Interest Agreement” from April 2016. As the name indicates, these instruments are used to protect as privileged the discussions among parties having common interests in a legal proceeding. Those agreements are common—where there is actual or reasonably expected litigation—as is required for the use of said instrument.

In the AGs’ case, there was no relevant extant or reasonably anticipated joint or common legal proceeding. Nor has there been one since. The purpose of their pact, specifically its paragraph 6, requiring consultation among AGs about responding to public record requests, was to shield from public scrutiny the otherwise public record of their efforts to defend President Obama’s global warming policy agenda and their own investigations of political opponents for alleged racketeering or financial fraud deriving from their opposition to the climate policy agenda. After an extended delay brought on by litigation, which was itself forced by stonewalling, courts have held that this arrangement offers the AGs no such shield.32 Numerous other AGs have effectively agreed with this finding, choosing not to fight that battle but instead to realease the correspondence that was purportedly shielded and in many cases withheld by their partners.

Those state-level open records productions, which revealed close orchestration with plaintiffs’ lawyers and environmental activists, proved costly to that coalition and scared off participants while discrediting said investigations. This approach, in turn, likely prompted Schneiderman and company to consider how to pursue such a political coalition while keeping the public records from the public. Critically—and as one email from NYU’s Elizabeth Klein to the Illinois OAG discussed later suggests— Bloomberg’s program aims not only to provide the activist AGs a home to get the band back together, but also to supply another bite at claiming attorney–client and “work product” privileges to shield their work going forward.

The 2016“informal coalition”in practice sought to extract three things from its targets: (a) a vow of silence, (b) a vow not to financially support other opponents of the agenda (like the subpoenaed CEI),33 and (c) a settlement fund in the hundreds of billions of dollars modeled on the tobacco master settlement agreement (MSA).

As in the tobacco MSA, this settlement, in large part, would fund more activist government and would be distributed among political constituencies.34 The same is true of any settlement obtained in the staggered series of lawsuits filed against major energy producers by coastal municipalities such as Marin County, Oakland, and San Francisco in the summer and fall of 2017; New York City in January 2018; inland liberal enclaves such as Boulder, Colorado, in April 2018; and the state of Rhode Island—home of Schneiderman coalition partner Peter Kilmartin and Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, a major proponent of using the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) against political opponents—in July 2018.

The first record production on the 2016 campaign, from the Vermont OAG, included responses to a questionnaire sent to the state AGs by Schneiderman’s office. U.S. Virgin Islands AG Claude Walker reveals his interest, having“just finished litigation against Hess Oil … [obtaining an] $800 million settlement.” Walker goes on to express interest in “identifying other potential litigation targets” and in seeking ways to“increase our leverage.”35

After the first production of these damning public records, the Vermont OAG sealed up tight, and other OAGs facing record requests followed suit. Speaking at least in part regarding the ongoing campaign of stonewalling state FOI requests (after reciting some highlights of what was known at the time about this collaboration with plaintiffs’ lawyers and activists), one federal court noted that these AGs ought to drop the fight and release the requested public records in the name of dispelling speculation on what these revelations indicated was going on:

[New York] Attorney General Schneiderman and [Massachusetts] Attorney General Healey, despite these media appearances by both, are not willing to share the information related to the events at the March 29, 2016, meeting at the AGs United for Clean Power press conference. Should not the attorneys general want to share all information related to the AGs United for Clean Power press conference to ensure the public that the events surrounding the press conference lacked political motivation and were in fact about the pursuit of justice? The attorneys general should want to remove any suspicion of the event being politically charged since it was attended by (1) former Vice President Al Gore, a known climate change policy advocate in the political arena; (2) Mr. Peter Frumhoff, a well-known climate change activist; and (3) Mr. Matthew Pawa, a prominent global warming litigation attorney who attended a meeting two months prior to the press conference at the Rockefeller Family Fund to discuss an “Exxon campaign” seeking to delegitimize Exxon as a political actor. Any request for information about the events surrounding the AGs United for Clean Power press conference should be welcomed by the attorneys general.36

The judge noted that efforts to keep public records from the public, as was suggested in their “common interest agreement,” “causes the Court to further question if the attorneys general are trying to hide something.”

The settlement fund sought by this campaign is enormous. The figure publicly bandied about is $200 billion—perhaps because that was the approximate value of the 1998 tobacco MSA providing the plaintiffs’ lawyers’ and consultants’ settlement template.37 Hydrocarbon energy, however, is a much bigger industry than tobacco.

At least one prominent academic, Edward Maibach, director of the Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University (GMU), has admitted to an expected payout from this campaign for his type of work. Maibach’s background is in public relations, in which business he served as worldwide director of social marketing for the PR firm Porter Novelli and where he worked on distribution of the tobacco master settlement funds. He told Grist magazine in an interview about his new work promoting the climate campaign, which we learned also entailed recruiting academics to call for RICO investigation of that campaign’s opponents:

If the White House took up Sen. [Sheldon] Whitehouse’s suggestion to wage a full investigation into the fossil fuel industry for all of their collusion and stonewalling to confuse the public about the harm of fossil fuels, and if a RICO suit were successful, and if there was a

settlement between the government and the fossil fuel industry—there is no question in my mind that a good portion of that money should be spent on a national campaign to educate people on the risks of climate change, and [to] build their resolve to work towards solutions. If this were treated as a public health problem, that is exactly what would be done.38

CEI and this author filed a Virginia FOIA suit, Horner et al. v. George Mason University,39 after some GMU faculty members led by Maibach worked with Sen. Whitehouse in calling on then-U.S. AG Loretta Lynch to go after their agenda’s opponents under an antiracketeering law. In a deposition in the matter in which this author participated, Maibach testified thus in response to my question:

Q. As director of the Center for Climate Change Communication, what do you do?

A: … As director, I suppose my chief job is raising the money we need to do the research, actually overseeing the research so that it is done of sufficient quality, mentoring my post docs, my students, my faculty, keeping the ship moving forward.

He was then asked if he recalled that Grist interview. He did, and soon he modified his previous answer about priorities:

Q. You testified that your earlier job in that position is raising funds?

A. Part of.

Q. You said your chief job was the quote. We can go back. Your chief job is raising money to keep it going. Is that still accurate?

A. That is probably a little too glib…. 41.

When Maibach asked Peter Frumhoff of the Union of Concerned Scientists to enlist UCS in publicly calling for RICO investigations of their opponents, Frumhoff let on to the brewing state AGs’ campaign, months before it became public. In a July 31, 2015, email, Frumhoff first dismissed Maibach’s call for a federal RICO investigation:

As you know, deception/disinformation isn’t itself a basis for criminal prosecution under RICO. We don’t think that Sen. Whitehouse’s call gives enough of a basis for scientists to sign on to this as a solid approach at this point.42

Then, Frumhoff assured Maibach,“[W]e’re also in the process of exploring other state-based approaches to holding fossil fuel companies legally accountable … [via] state (e.g., AG) action.”43

So far, two courts in Texas have issued scathing rulings noting these revelations: one the aforementioned federal district court for the Northern District of Texas44 and more recently a state court in Tarrant County.45 The federal district courtfocusedonanemailinwhich Schneiderman’s office asks activist lawyer Matt Pawa to mislead a reporter about his role in briefing the AGs and Al Gore in the back room just before the March 29, 2016, Manhattan press conference announcing a whatever-means-necessary campaign against opponents.46

This email references Pawa and Frumhoff, who both participated in the January Rockefeller/“delegitimize” meeting and the 2012 La Jolla conference; they had been invited to

Figure 4

secretly brief the state AGs. At that briefing, held immediately before the AGs’press conference, they each received 45 minutes to provide arguments on “climate change litigation” and “the imperative of taking action now,” according to the agenda prepared by Schneiderman’s office and circulated to participating OAGs.47

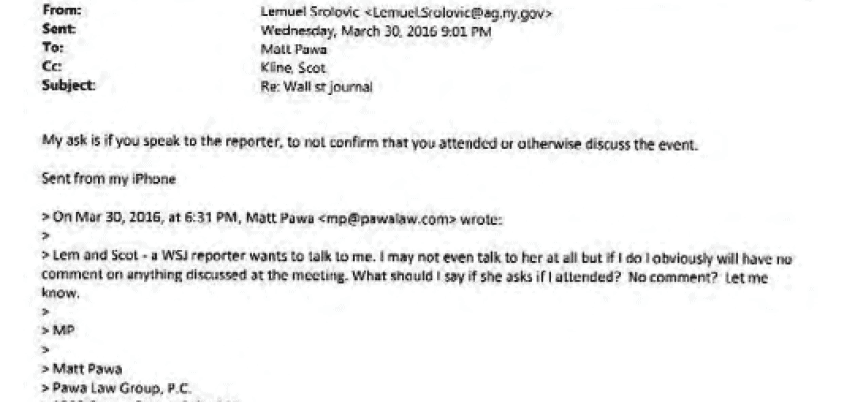

The day following the press conference, March 30, 2016, Pawa wrote to Lem Srolovic of Schneiderman’s office and Vermont Deputy AG Scot Kline seeking help. A Wall Street Journal reporter wanted to talk to Pawa, and he asked the two officials: “What should I say if she asks if I attended?”

Srolovic replied: “My ask is if you speak to the reporter, to not confirm that you attended or otherwise discuss the event” (see Figure 4).

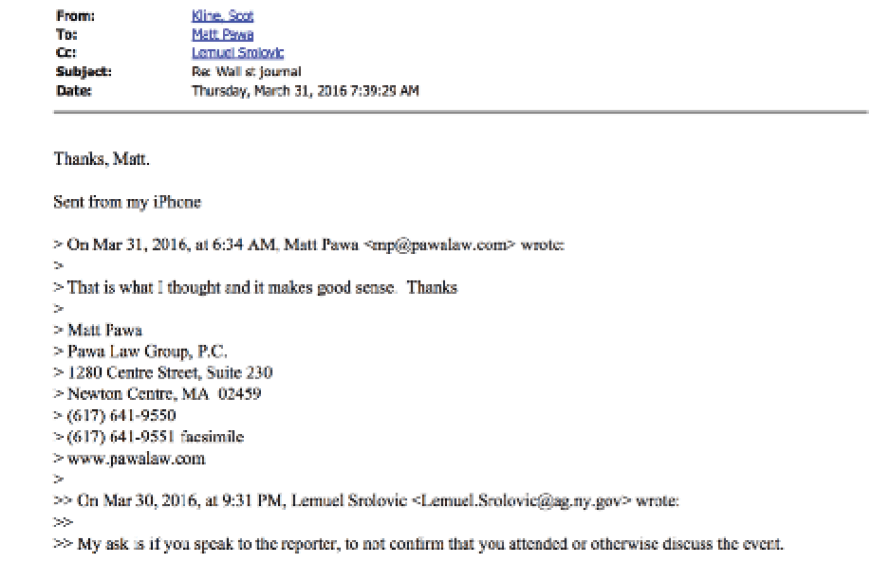

Two more parts of the email thread between Pawa and the New York and Vermont state AG offices—which New York released but Vermont did not—reveal Pawa agreeing that this “makes good sense” and Vermont’s AG office thanking him for this willingness to stay mum (see Figure 5). In fact, stonewalling by the Vermont OAG was so egregious that, after ordering it to release certain documents central to this paper in December 2017, the court awarded requesters every dollar requested, for every hour requested, at the rate requested—which is almost unheard of in open records cases.48

In 2017, the Texas federal court also noted, “Does this reluctance to be open [about collaborating with plaintiffs’ attorneys and activists with a litigation agenda] suggest that the attorneys general are trying to hide something from the public?”49 The same court took notice of Frumhoff’s advisory role—or rather, what was known thanks to open records productions at the time. Then, in late April 2018, over two years after we began extracting the records from increasingly reluctant participating OAGs, the District Court of Tarrant County, Texas, ruling

Figure 5

that the court could order Pawa to face pre-suit discovery (and likely deposition) cited certain revelations about the scheme uncovered thanks to FOIA:

State Attorneys General Conceal Ties to Pawa

- At a closed-door meeting held before the March 2016 press conference, Mr. Pawa and Dr. Frumhoff conducted briefings for assembled members of the attorneys general’s offices. Mr. Pawa, whose briefing was on “climate change litigation,” has subsequently admitted to attending the meeting, but only after he and the attorneys general attempted and failed to conceal it.

- The New York Attorney General’s Office attempted to keep Mr. Pawa’s involvement in this meeting secret. When a reporter contacted Mr. Pawa shortly after this meeting and inquired about the press conference, the Chief of the Environmental Protection Bureau at the New York Attorney General’s Office told Mr. Pawa, “My ask is if you speak to the reporter, to not confirm that you attended or otherwise discuss the event.”

- Similarly, the Vermont Attorney General’s Office—another member of the “Green 20” coalition—admitted at a court hearing that when it receives a public records request to share information concerning the coalition’s activities, it researches the party who requested the records, and upon learning of the requester’s affiliation with “coal or Exxon or whatever,” the office “give[s] this some thought … before [it] share[s] information with this entity.”50

In preparing for a briefing by and with AG lawyers at a different “secret meeting” discussed below, Frumhoff also laid out an argument in an April 2016 email to Oregon State Professor Mote that “I’ve made in previous talk [sic] to AG staff.”51

Possible reasons for keeping both advisors’ role quiet have continued to emerge with more recent record productions.

These new records also provide more than an alleged “missing link between the [lawyers and] activists and the AGs,” claimed by a later federal judge who was far more dismissive of the evidence known earlier in 2018, before the Tarrant County Court also ruled.52

The Seeds of Privately Funded “Climate” Law Enforcement

STATE ATTORNEYS GENERAL, GREEN GROUPS, “PROSPECTIVE FUNDERS,” AND THE “SECRET MEETING”

Strongly negative media attention followed the initial 2016 OAG open record productions that detailed the collaboration between green-group activists, plaintiffs’ lawyers, and AG offices. U.S. Virgin Islands AG Claude Walker, who issued the subpoena against CEI, retreated when CEI filed litigation against him for the move. Amid all of this came seemingly coordinated OAG stonewalling of further requests.

This stonewalling was presaged in the Common Interest Agreement noted earlier. Its sixth paragraph calls for consultation among the OAGs about public records requests prior to releasing such records to the public.53 Vermont Deputy AG Scot Kline accurately characterized the agreement as suggesting “an affirmative obligation to always litigate those issues.”54 As noted, Vermont’s OAG eventually was ordered

by a court to pay $66,000 in legal fees and court costs over its resulting stonewalling.

Over a year and a half after those first requests, in December 2017 that same Vermont court ordered an important document production to be pried from the Vermont AG’s litigious grasp. This production included an agenda for a briefing at Harvard University Law School, which was co-hosted by the Union of Concerned Scientists and involved senior attorneys from the activist OAGs. The subject was “Potential State Causes of Action against Major Carbon Producers”—that is, climate-related suits that the AGs might file against energy companies. Leaving no doubt, one panel addressed “The case for state-based investigation and litigation.”55 It included much of the cast from the 2012 La Jolla meeting. References to “the Harvard event” appear throughout OAG correspondence produced in 2016.56 Emails later obtained described it as follows:

- An event designed “to inform thinking that is already under way in state AG offices around the country regarding legal accountability for harm arising from greenhouse gas emissions” (recall the July 2015 email from Frumhoff to Edward Maibach describing that “legal thinking already under way”);57

- “[A] private event for staff from state attorney general offices:”58

- The “carbon producer accountability convening;”59 and

- A“climate science and legal theory meeting.”60

Emails from Harvard to senior OAG attorneys make clear that Schneiderman’s office was involved in organizing participants:

Alan Belensz, Chief Scientist in the New York Attorney General’s office, suggested that I reach out to you …”61

[Assistant Attorney General] Michael Myers from the [New York] AG’s office suggested that I reach out to you.62

Harvard Law clinical instructor Shaun A. Goho, who previously worked for the green litigation group Earth Justice, led the effort to organize the April 2016 briefing. He noted: “[W]e know that there will be people from at least

… California, Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, and New York.”63

Interestingly, given follow-on lawsuits filed by cities and counties, emails suggest the April 2016 “secret meeting” among law enforcement, plaintiffs’ lawyers, and activists also included municipalities.64 Other April 2016 emails show the involvement of Steven Berman, the municipalities’ lawyer in their 2017 climate lawsuits, in the effort to recruit AGs to investigate opponents of the climate agenda.

Thanks to the court-ordered Vermont production in December 2017, we know that the meeting at Harvard also included other parties critical to the success of this briefing on a climate litigation strategy, in which AG offices participated. Although listed nowhere on the agenda, emails state that participants included donors, whose funding makes possible the collaborative, public–private partnership that is the climate litigation industry.

The Vermont OAG had withheld the Harvard agenda on implausible claims of attorney- client privilege and attorney work product. The document was drafted by a law school clinical instructor and widely shared among academics, activists, and—apparently—their financial supporters. The meeting agenda’s title, “Potential State Causes of Action against Major Carbon Producers,” reaffirmed that the purpose was to develop “state causes of action”—AG investigations and lawsuits. Whom the attorney and the client might be among these parties is not at all clear. It took a year and a half of Vermont dragging this out in litigation, but the courts agreed:

Document ·143-Bates 834-835

This document shall be produced. It is a draft agenda for a meeting of attorneys and others evidently on general subject areas and interests “co-organized” by Harvard Law School and the Union of Concerned Scientists. Any claim of privilege is too remote and no apparent prejudice will result from production. That segments of the meeting have delved into confidential matters is insufficient to show that the draft agenda also is.65

Given further revelations from record productions received in 2018, the claims of phantom privilege suggest apprehension over the prospect of this document’s seeing the light of day. Details were going to emerge; the only real question was when. What to do?

The host groups decided to belatedly blog about the event as if it were routine, responding to charges not made by anyone, what with the briefing being “secret,” and therefore not (yet) public knowledge. UCS’s Frumhoff,after appealing to his longtime involvement with the issue, closed his May 11, 2016, blog post with “Harvard Law School routinely hosts meetings that provide policy makers with opportunities to confer with scholars and practitioners. State attorneys general and their staff routinely confer privately with experts in the course of their deliberations about matters before them.”66 For its part, Harvard stated in an undated May 2016 post: “It is the normal business of Attorneys General staff to keep informed and to have access to the latest thinking about issues important to their work.”67

Neither post mentioned that participating

plaintiffs’ attorneys had been introduced to AGs by at least one major donor to make their pitch. Neither hinted that UCS paid AG lawyers’ way. Neither noted that this meeting, for which OAG attorneys flew in to assist with possible AG investigations and lawsuits, was in fact a green- group fundraiser.

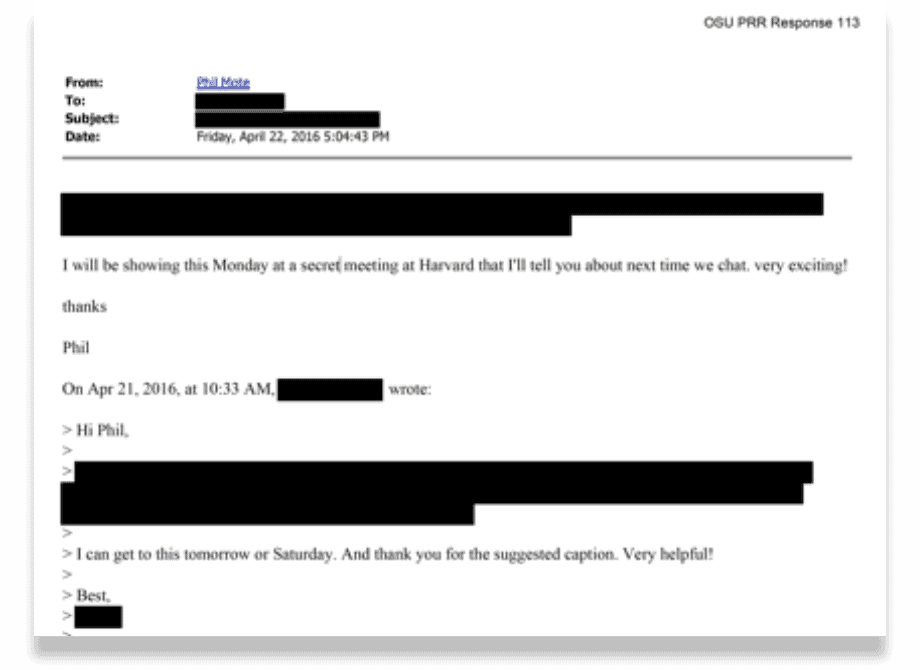

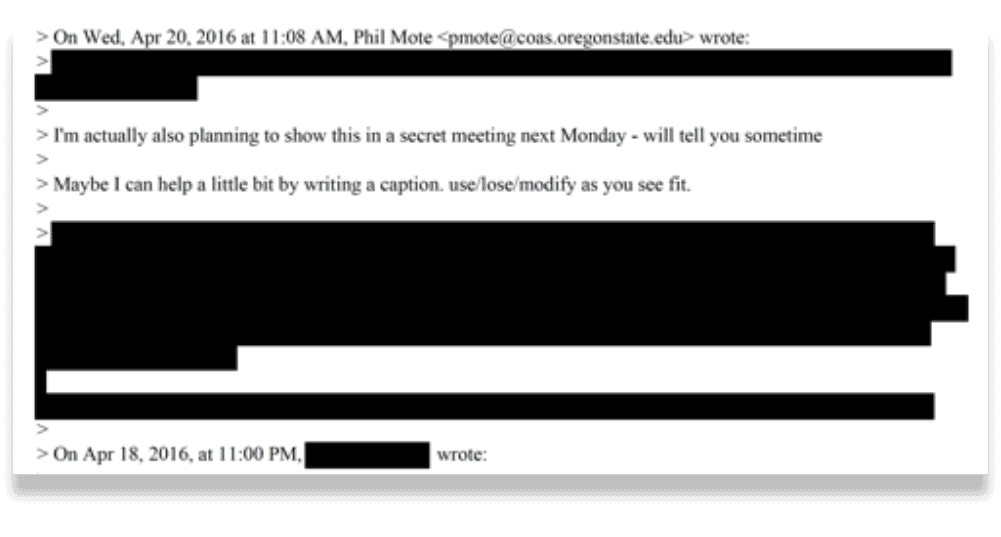

These may be reasons why one participant described it as “a secret meeting at Harvard.” In late March 2018, Oregon State University released certain records in response to a CEI records request prompted by the Harvard agenda. Those records included correspondence of Oregon State Professor Philip Mote, who presented at Harvard to OAG attorneys and donors about the climate litigation strategy, apparently in his capacity as an OSU instructor (see Figures 6 and 7). The emails show Philip Mote boasting to (apparently) two parties whose identities the school has redacted, “I will be showing this Monday at a secret meeting at Harvard that I’ll tell you about next time we

Figure 6

Figure 7

chat. [V]ery exciting!”68 Also, “I’m actually also planning to show this in a secret meeting next Monday—will tell you sometime.”69

Unfortunately, Mote permanently deleted the presentation, although he forwarded it to his confidants and some green-group activists and presented it to AG staff members, the Union of Concerned Scientists, and their prospective funders. The school assured CEI that this was simply normal practice because the files were large, while also redacting (a) the emails’ subject lines, (b) the identities of Mote’s correspondents, and (c) much of what they discussed.70

In his email invitation to Oregon State’s Mote, UCS’s Frumhoff describes the event as “an off-the-record meeting of senior staff from attorney’s [sic] generals offices from several states to discuss with them the state of climate science (including extreme event attribution) and legal scholarship relevant to their interests.” In the same email, Frumhoff then tells Mote: “We will have as small number of climate science colleagues, as well as prospective funders, at the meeting.”71 [Emphasis added]

Mote replied, “[T]hat would be an amazing experience.”

The Harvard “secret meeting” agenda and correspondence indicates this session was to strategize about the private litigants’ cases but leaves no doubt that the focus was to discuss how to ensure that AGs would pursue their own investigations and litigation. The panic about releasing this agenda became more understandable after CEI received the production from Oregon State.

These AGs, led by New York’s Eric Schneiderman and Massachusetts’s Maura Healy had, just weeks before the “secret meeting,” vowed at a press conference to use any means necessary to go after opponents of the political agenda, immediately following a briefing from some of the same presenters, whom the OAGs also asked to deny their role in briefing the AGs and Gore.

CEI has obtained one other relevant document from the office of California’s AG, which instigated its involvement in this campaign during the tenure of Kamala Harris, who is now a U.S. Senator. This three-page “Bios” PDF was circulated among California Department of Justice attorneys on April 27, 2016. It apparently pertains to the Harvard strategy session, but it was not withheld as privileged. The bios are of seven academic and other activist parties listed on the Harvard/ UCS/OAGs agenda. The document is headed at the top of page one: “Technical Advisors and Experts.” It is a “white paper” with no information provided regarding authorship or whom these experts advise.

This was foretold in an April 2016 email, to

a bcc: list of recipients from UCS’ Erin Burrows, further affirming Mote’s characterization of the “secret meeting”: “As part of the materials to be distributed at the convening on 4/25, we would like to include names (w title/organization) and bios of technical experts. No contact information will be provided nor will the bios handout include any specifics about the event itself.”72

Birth of a New Home for the “Sympathetic Attorneys General”

WITH THE PASSAGE OF TIME, WE now see where all of this was headed. As the FOIA litigation ground slowly through the state courts, a new scheme was ultimately arrived upon that gives the troubling appearance of a donor buying a seat at the law enforcement table. This is the Bloomberg “legal fellow” program described earlier and that involves having private activists funding and placing activist lawyers in law enforcement offices to “advance progressive clean energy, climate change, and environmental legal and policy positions.”73 It offered the express inducements of a PR team and “pro bono” legal network as part of a package deal for AGs who will accept one or more privately funded “Special Assistant Attorneys General” to pursue an agreed-upon agenda.

Under Bloomberg’s arrangement with NYU, state AGs must abandon their model of the client—the AG or other state agency for whom the SAAG is engaged—paying counsel. Instead:

- The OAG applies to NYU for a “Special Assistant Attorney General” to be provided to it by NYU’s Center and expressly to perform work that it otherwise would not or could not do in the field of “advancing progressive clean energy, climate change, andenvironmental legal positions” unless the donor provided the resources.

- Once approved, the OAG agrees to “hire” NYU, not for payment but for providing office space to the NYU employee.

- NYU agrees to pay and hires a lawyer as a “Research Fellow” to act as its employee in the OAG.

- NYU seconds the attorney to OAG.

- The AG appoints the activist lawyer as a “Pro [B]ono Special Deputy Attorney General.”

- OAGs regularly report to NYU on their work to “advance progressive clean energy, climate change, and environmental legal and policy positions.”

Most troubling about this arrangement is that any promised enforcement actions and investigations would target a readily identifiable, finite universe of parties. “I think that problem would be apparent to anybody if you’re talking about a conservative donor paying for a special attorney general to investigate and prosecute Planned Parenthood on any possible ground that might be out there,” said Andrew Grossman, a BakerHostetler law partner and Cato Institute adjunct scholar who has participated in cases on related issues.74 “These arrangements were being made with a clear end in mind to target particular industries and particular companies.”75

STRANGE BEDFELLOWS

This process began in August 2017 with the email from David Hayes described earlier to nearly two dozen state AG offices, notifying them of the program and of a September 15, 2017, application deadline.76

First, our Center will have three full-time attorneys who will be available to provide direct legal assistance to interested AGs….

We look forward to developing a working relationship with your offices and serving as a source of ideas, materials, and contacts on these matters. In that regard, we will maintain a set of on-going relationships with advocates working in the area, and we also are identifying pro bono services that may be available to your offices on individual matters.

Second, our Center will have a full-time communications expert in the clean energy, climate, and environmental field to work with, and help leverage, the communications resources in your offices.

It’s in everyone’s interest that we work with the relevant AGs and hire these lawyers as soon as practicable.77

Note the suggestion that further outside “pro bono” counsel may be made available to buttress OAG work of interest to Bloomberg’s NYU group—compounding the concerns raised by the placement of private ‘Special AGs.’”

Hayes added:

Finally, please note that the State Energy & Environmental Impact Center’s attorneys and communications staff will be located in Washington, D.C. Our offices are at 1616 P Street NW, near DuPont Circle. (The 10 Special Assistant AGs, of course, will be located in the host AGs offices.)

I am heading up the Center, and Liz Klein is the Deputy Director. You can reach us at [email protected] and Elizabeth.Kline@ nyu.edu. We are in the process of hiring an additional attorney and our full-time communications staff.78

That address is that of the aforementioned Resources for the Future, which lists no affiliation with Hayes or NYU. Perhaps the group is merely a landlord to this operation. Other emails obtained by CEI show that Hayes personally discussed the idea with various attorneys general he sought to recruit prior to their offices’ participation. For example, Hayes wrote to Virginia’s Donald Anderson, Senior Assistant Attorney General and Chief of the Virginia OAG’s Environmental Section, seeking a meeting with Virginia AG Mark Herring, “Liz and I would appreciate the chance to come down to Richmond and visit with AG Herring and the team to discuss how we can work together. I’ve had similar meetings with the other AGs that are bringing on Special Assistant AGs, and other AG who we are working with.”79

Hayes suggested that the insertion of Bloomberg/NYU into those offices extends beyond the SAAG program, which has only “funding to recruit and hire 10 NYU fellows who will serve as Special Assistant AGs, working as part of the state OAG’s staff.”80 Other emails show that members of the Bloomberg/NYU Team81 were included on more general “multistate AG coordinating calls,” as the sole visibly copied outside party in presumably privileged discussions of litigation strategy.82

MODEL BEHAVIOR?

NYU provided state AG offices with a model job description, then worked with the OAGs to tailor it to their individual formats.

This description is quite open about the NYU Center’s objectives, which include the following:

The opportunity to potentially hire an NYU Fellow is open to all state attorneys general who demonstrate a need and commitment to defending environmental values and advancing progressive clean energy, climate change, and environmental legal positions …

Candidates who are approved by the attorneys general and the State Impact Center will receive offers to serve as SAAGs (or the equivalent appropriate title within the office) from the attorneys general, based on an understanding that they will devote their

time to clean energy, climate change and environmental matters. [Emphases added.]

NYU’s model job description states that SAAGs will do the following:

Coordinate with relevant parties on legal, regulatory, and communications efforts regarding clean and affordable energy and other related environmental issues.…

Advance clean energy and environmental legal and policy positions.

Defend environmental values.

Prepare periodic reports of activities and progress.83

INDUCEMENTS

The latter is, by contract, what the AG’s office will communicate to NYU in regularly scheduled updates, as the OAG’s consideration to the donor for receiving (a) the attorneys, (b) a “pro bono” legal network for issues that particularly interest the Bloomberg operation, (c) in-house NYU legal staff, and (d) a communications aide (“legal and communications resources [through NYU] … as well as through our connections with pro bono counsel and other resources”).

That is, the agreements state clearly that the relationships between the NYU Impact Center and the AG offices extend far beyond placing an attorney in a state AG office. In effect, each SAAG is part of a package deal. The larger package of inducements might

have helped AGs move beyond any discomfort over potential impropriety or simply the terrible optics of signing an agreement to “[c]oordinate with the [NYU/Bloomberg] State Impact Center and interested allies on legal, regulatory, and communications efforts regarding clean energy, climate change, and environmental issues” and “[p]repare periodic reports of activities and progress to the State Impact Center” in return.

AG, the joke goes, stands for Aspiring Governor. For the same reasons, one of the most attractive aspects of this package was likely the communications function.

NYU wrote to Oregon’s OAG after tying the knot but still months away from consummating:

We noted that one of the State Impact Center’s most important tasks, from our perspective, is to deploy effective communications strategies that will draw attention to key state AGs’ initiatives in the clean energy, climate, and environmental arena.

Our Communications Director, Chis Moyer, is our point on this. We are eager to have Chris stay in close touch with Kristina and help draw attention to the important clean energy, climate, and environmental work that your office is engaged in. Most recently, we helped AGs Frosh, Herring, and Racine develop an op-ed that they published in last Sunday’s Washington Post on threats to Chesapeake Bay restoration activities.84

A December 6, 2017, email from the Pennsylvania Chief Deputy Attorney General Steven J. Santarsiero to NYU’s Elizabeth Klein suggests that the communications services are not limited to the NYU-based aide. In the email with the subject line “NYU Law Fellow Program,” Santarsiero tells Klein: “As we discussed, I am copying our Communications Director, Joe Grace, on this email so that you can connect him with the communications folks in CA.”

There are no other indicators of who such a vendor might be. However, California- based Resource Media, which promoted the municipalities’ climate litigation, is the “agency of record” for the Skoll Foundation, an activist philanthropy.85 Skoll also founded Participant Media, which produced former Vice President Al Gore’s “Inconvenient Truth” films.”86

Like the other inducements, this one raises questions under various state laws: Is this provision of outside consultants on a donor’s tab a gift? Does it violate gift limits? Are the gifts properly reported? Is it an improper benefit? Is this sort of private provision of government services unlawful in that jurisdiction, as it would be at the federal level under the Antideficiency Act—a law enacted to prevent a variety of abuses, including the bestowing of private benefits and avoiding officials incurring obligation to private parties?87 Then there are 14th Amendment and other constitutional and ethical issues are raised and described herein.

The bigger-picture questions remain: Is Michael Bloomberg (a) going to such lengths to avoid directly placing chosen lawyers in AG offices or (b) giving the money to do so directly to the offices, because he is barred from doing so? Or is the effort creating middlemen all merely due to appearances? Is this project an attempt to manufacture a “safe harbor” of attorney–client privilege in coordinating pursuit of political opponents?

And the biggest issue of all is, as Baker Hostetler’s and Cato’s Andrew Grossman suggests, “What you’re talking about is law enforcement for hire.

… Really, what’s being done is circumventing our normal mode of government.”88

The office of Maryland AG Brian Frosh redacted the following descriptions of the NYU- provided work from this office’s contract before releasing it. The parts that Maryland viewed as somehow privileged—which portions were released in Oregon’s unredacted production— are in italics:

The Attorney General of the State of Maryland (“OAG” or “Client”) and New York University on behalf of the lawyers at the State Energy & Environmental Impact Center at NYU School of Law (“Counsel”) agree to the following arrangement regarding Counsel advising Client from time to time on administrative, judicial, or statutory matters involving clean energy, climate change, and environmental protection (the “Subject Matters”), including advice on the Subject Matters as may be sought in connection with potential litigation brought by or involving OAG. …

A. SCOPE AND NATURE OF ENGAGEMENT

1. Counsel has agreed to advise OAG on the Subject Matters, including in connection with potential litigation to the Subject Matters to be brought by or involving OAG. Counsel’s engagement is limited to advising the OAG on the Subject Matters only and does not include any commitment or undertaking to appear or represent or to advise the OAG in any proceeding or litigation or to advise the OAG in any other matter, proceeding or litigation.

The same office redacted all mention of the scope of work from the secondment agreement, including (redactions in italics):

B. Nature of the Fellowship Position at OAG

2. OAG will assign the Legal Fellows substantive work and responsibility matching that of other attorneys in the agency with similar experience and background. The Legal Fellow’s substantive work will be primarily on matters relating to clean energy, climate change, and environmental matters of regional and national importance. …

4. In addition to the formal reporting requirements, OAG and the Legal Fellow will collaborate with the State Impact Center on clean energy, climate change, and environmental matters in which the Legal Fellow is engaged, including coordination on related public announcements. [Emphases added.]

OAGs Applying Themselves

INTERESTED OFFICES WERE TO follow specific instructions from the NYU Center when applying, including stating what the OAGs would do about the desired areas of investigation and enforcement if a donor were INTERESTED OFFICES WERE TO provide the resources to pursue them.

The objectives are inherently and expressly ideological.89 First, applicant OAGs must “demonstrate a need and commitment to defending environmental values and advancing progressive clean energy, climate change, and environmental legal positions.”90 Other specifics include these:

Application Requirements

To be considered for the NYU Fellows/ SAAG program, an application must contain the following:

1. Program Eligibility and Narrative

State attorneys general should describe the particular scope of needs within their offices related to the advancement and

defense of progressive clean energy, climate change, and environmental matters. …

Priority consideration will be given to state attorneys general who demonstrate a commitment to and an acute need for additional support on clean energy, climate change, and environmental issues of regional or national importance, such as those matters that cross jurisdictional boundaries or raise legal questions or conflicts that have nationwide applicability.

Each application, therefore, affirms that those OAGs are not merely doing what they otherwise would have done but are expressly stating that, but for the inducements, they would not do the particular work. Some were quite explicit.

After OAGs applied, NYU wrote in mid- October 2017 to let applicant offices know they had “reviewed applications received from 11 and have selected 7 jurisdictions to receive the initial tranche of Law Fellows.”91 Beginning three weeks after the application deadline, NYU notified successful applicants:

We are very much looking forward to supporting your important work in the clean energy, climate, and environmental arena through the SAAG program and the State Impact Center.92

Successful applicants were asked for further meetings with senior AG office attorneys to address “how we might best help support your work, particularly with regard to regional and national issues that AGs are getting engaged in in the climate, clean energy, and environmental arena.”93 Later NYU followed up with OAG staff members about meeting to nail down the agenda: “We are excited to partner with your office!”94

NYU informed offices that were not selected:

As the hiring of our initial group of Law Fellows proceeds, we expect to confirm the availability of funding for additional Law Fellows, and [we] may be back in touch with you, in the hope that we might be able to reactivate your application.

In the meantime, the State Impact Center looks forward to helping support your work on clean energy, climate, and environmental matters through the legal and communications resources that we have at the Center, as well as through our connections with pro bono counsel and other resources. In that regard, we will be following up with you to discuss how best to facilitate an effective working relationship.95 [Emphasis added]

When it came time to formalizing its stable of law enforcement offices engaged to pursue its climate agenda, NYU’s Bloomberg-funded Center laid out its role and involvement in three key documents: the Position Description, Employee Secondment Agreement, and Retainer Agreement. Excerpts include:

NYU Law Fellow Position Description …

SAAGs will be hired for a term appointment to provide a supplemental, in-house resource to state AGs and their senior staffs on clean energy, climate change, and environmental matters of regional and national importance. As allowed under state law, NYU School of Law will pay the salaries of the SAAGs, and the State Impact Center will provide on-going support to the SAAGs and their offices. Once hired, the SAAGs’ duty of loyalty shall be to the attorney general who hired them.…

Responsibilities include but are not limited to the following:

- Defend environmental values, and advance

progressive clean energy, climate change, and environmental legal and policy positions.

- Subject to the specific scope of assigned

duties by the relevant state AG, perform highly advanced legal work, which might include (a) conducting in-depth analysis and preparation of legal memoranda;

- interpreting laws and regulations; (c) providing legal advice; and (d) assisting in preparing legal notices, briefs, comment letters, and other associated litigation and regulatory documents.

- Coordinate with the State Impact Center

and interested allies on legal, regulatory, and communications efforts regarding clean

energy, climate change, and environmental issues.

- Prepare periodic reports of activities and

progress to the State Impact Center.…

Requirements and qualifications:…

- Ability to work with partner organizations and to help build coalitions.

[Emphases added.]

This description reads like a typical environmentalist pressure group’s notice of a position opening. NYU then fleshed out the mechanics of the unusual arrangement. Draft secondment and retainer agreements offered to the AGs read in pertinent part:

Employee Secondment Agreement …

WHEREAS, [t]he [AG OFFICE] has

been selected by the State Impact Center to participate in Legal Fellowship Program; and

WHEREAS, [t]he [AG OFFICE] has the authority consistent with applicable law and regulations to accept a Legal Fellow whose salary and benefits are provided by an outside funding source.…

A. Terms of Service …

[T]he term of the fellowship will be for one year with the expectation that a second one- year term will follow after mutual agreement among the parties.…

[S]alary and benefits will be provided to the Legal Fellow by the NYU School of Law.… The [AG OFFICE] will aim to include the Legal Fellow in the range of its work where possible, such as strategy discussions.… [There follows some boilerplate language designed to insulate the 501(c)3 from allegations that the placed attorney does not constitute a gift and is not engaged in propaganda, by declaring that is not the case.]

D. Communications and Reporting

The State Impact Center will not have a proprietary interest in the work product generated by the Legal Fellow during the fellowship. The State Impact Center will not be authorized to obtain confidential work product from the Legal Fellow unless the Legal Fellow has obtained prior authorization from the Legal Fellow’s supervisor at the [AG OFFICE].

2. Notwithstanding the above, the [AG OFFICE] will provide periodic reports to the State Impact Center regarding the work of the Legal Fellow. These reports will include a narrative summary, subject to confidentiality restrictions, of the work of the legal fellow and the contribution that the legal fellow has made to the clean energy, climate change, and environmental initiatives of the [AG OFFICE]. These reports will be provided pursuant to the following schedule:

-

Activity for the period from the beginning of the Fellowship Period until April 30, 2018, will be provided no later than May 1, 2018.

-

Activity for the period from May 1, 2018, through July 31, 2018, will be provided no later than August 1, 2018.

-

Activity for the period from August 1, 2018, through January 31, 2019, will be provided no later than February 1, 2019.

-

A final report for activity from the beginning of the Fellowship Period until the end of the Fellowship Period will be provided within five

(5) business days of the end of the Fellowship Period.…

-

In addition to the formal reporting requirements, the [AG OFFICE] and the Legal Fellow will collaborate with the State Impact Center about clean energy, climate change, and environmental matters in which the Legal Fellow is engaged, including coordination on related public announcements.

Responding to Funders and Legislative Failures—Legal and Ethical Flags

PUBLIC RECORDS INDICATE THAT At least six state AG offices (including the District of Columbia) have brought on board a Special Assistant AG to advance climate policy—paid mid-high five to six figures by a private donor—each with additional sweeteners of in-house NYU lawyers and PR staff and an outside PR and legal network.96 Those six jurisdictions having brought one or more SAAGs into their fold—Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Oregon, Washington, and the District of Columbia—are all charter members of the collapsed Schneiderman-led “Climate-RICO” coalition.97

Substituting Law Enforcement for a Failed Political Agenda

THERE SHOULD BE LITTLE ARGUMENT over whether substituting litigation for a failed policy campaign undermines democratic governance and representative government. Similarly, it seems beyond dispute that this is not a proper use of law enforcement. It seems fairly well understood even that government should not be rallying political forces to go after opponents in court. The Washington Post in a 1999 editorial condemned the Clinton administration’s Housing and Urban Development Secretary Andrew Cuomo (now New York Governor) and his effort to use his position to sue gun manufacturers.

The Post confronted the practice thus:

[I]t nonetheless seems wrong for an agency of the federal government to organize other plaintiffs to put pressure on an industry— even a distasteful industry—to achieve policy results the administration has not been able to achieve through normal legislation or regulation. It is an abuse of a valuable system, one that could make it less valuable as people come to view the legal system as nothing more than an arm of policymakers.98

This aptly describes what is transpiring here, as state AGs use their offices to advance a failed political agenda. Before his role in the larger scheme was exposed, one of the plan’s key protagonists, plaintiffs’ lawyer Matt Pawa, admitted the campaign’s political nature in an interview with The Nation:

I’ve been hearing for twelve years or more that legislation is right around the corner that’s going to solve the global- warming problem, and that litigation is too long, difficult, and arduous a path. … Legislation is going nowhere, so litigation could potentially play an important role.99

Notably, a U.S. District Court dismissed a previous suit against ExxonMobil brought by Pawa on the grounds that regulating greenhouse gas emissions is “a political rather than a legal issue that needs to be resolved by Congress and the executive branch rather than the courts.”100 Possibly realizing the problem, Pawa subsequently denied the sentiment when emails showing his involvement emerged, telling the Washington Times that it is “inaccurate in attributing to me the idea that lawsuits should be used to achieve political outcomes.”101

Disgraced former New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman expressly linked his campaign to the stalled political agenda at the press conference with Al Gore, citing “gridlock in Washington” for his move “to step into this breach.”102

PROBLEMATIC OPTICS— OR WORSE?

By contract, the Bloomberg project at NYU is styled as the AGs’ attorney—paid by the donor, not the client. Some offices viewed by NYU or its benefactors as particularly important in the plan, including New Mexico and New York, were awarded two privately funded SAAGs. The AG offices, by contract, must provide regular updates to the entity paying for the SAAG, their health insurance and other benefits, and supplying the support network. By contract, the AG offices agree to provide office space and to share information with the NYU team. Nonetheless, loyalty is assured, by the same contract, to rest not with NYU but with the AG’s office.

Assurances aside, as a January 11, 2018, Wall Street Journal editorial noted about a similar scheme that we found placing privately hired and paid climate advisors in activist governors’ offices:

“Senior Policy Advisor, Climate & Sustainability” for Gov. Jay Inslee of Washington, Reed Schuler, who actually works, by donor arrangement, for a 501(c)3 called World Resources Institute: “This setup creates real concerns about accountability and interest-peddling. Mr. Schuler knows who pays him, and it’s not Washington taxpayers.”103

As Andrew Grossman notes, hiring Bloomberg-funded attorneys may run afoul of the 14th Amendment’s due process clause, given that the appearance that legal fellows brought on board with an OAG to pursue their private employer’s interests could have a financial interest in pursuing cases.104 The same applies to NYU providing the SAAG, a “pro bono” network of lawyers, and public relations advocacy. NYU surely would see an increase in support if its attorneys placed with AG offices achieved results in advancing “progressive clean energy, climate change, and environmental legal positions.” Similarly, this arrangement to pursue a funder’s policy priorities could create perverse incentives for AGs to investigate or file particular actions against certain industries or parties to keep the funding spigot flowing.

For instance, the New York OAG’s application demonstrated it warranted not one but two Bloomberg-funded lawyers by attaching a “Exhibit A (Select List of Actions”) of matters it was pursuing but for which—in order to continue,alongwithitsothercited“investigations and non-litigation advocacy” activities— “NYOAG has an acute need for environmental litigators.”105 Exhibit A covers 16 of what NYOAG says are 380 active cases handled by its Environmental Protection Bureau, and it prioritizes the sort of cases NYU’s Center cited as intending to support. The pursuit of energy companies for what NYOAG aspires to become actionable climate change offenses, and a litany of“non-litigation advocacy” or OAG Resistance activities against the Trump administration, are particularly telling.

NYOAG has an acute need for additional environmental litigators. First, the initial phase of fighting federal environmental rollbacks necessarily focused on … non- litigation advocacy. Opposing the Scott Pruitt nomination as EPA administrator, advocating the United States to remain in the Paris Climate Accord.