Chapter 10: Liberate to Stimulate

Policy makers frequently propose spending stimulus to grow or strengthen economies. That has certainly been the case during the past two years in response to COVID-19. A regulatory liberalization stimulus is the alternative to offer confidence and certainty to businesses and entrepreneurs. Businesses may sometimes value what they regard as a semblance of stability over the streamlining of rules. With respect to the transition from Trump to Biden, Fortune’s Geoff Colvin asked, “Why do so many CEOs welcome the seemingly hostile Biden’s victory?”:

The big, general reason many business leaders are fine with a President Biden is that they can’t take the tumult any longer. Business prizes stability, predictability, certainty. Trump’s incessant whipsawing on some of the largest issues—imposing tariffs, closing borders, retaliating against companies, leaving NATO—has exhausted businesspeople. As many of them say privately, they can compete so long as they know the rules, but can’t if the rules are constantly changing.

While there is value in stability, it can be compatible with regulatory streamlining, which can enhance it. Some future executive branch could take further steps beyond what Trump did on streamlining, leaning from what worked and what did not, such as requiring guidance to be submitted to Congress and to the GAO as required by the CRA. Such reform-oriented executive orders could include:

- Required review of independent agency rules

- Principles for guidance document preparation and disclosure

- Required preparation of the annual aggregate regulatory cost estimate already required by law but ignored

- Establishment of an “Office of No” chartered such that its role is purely to make the case against new and existing regulations.

Improving Regulatory Disclosure

Certainly, some regulations’ benefits exceed costs under the parameters of guidance to agencies, such as OMB Circular A-4, but for the most part net benefits or actual costs are not quantified. Without more thorough regulatory accounting than we get today—backed up by congressional certification of the specific interventionist actions agencies take—it is difficult to know whether society wins or loses as a result of rules. Relevant regulatory data should be compiled, summarized, and made easily available to the public. One important step toward better disclosure would be for Congress to require—or for the administration or OMB to initiate—publication of a summary of available but scattered data. Such a regulatory transparency report card could resemble some of the presentation in Ten Thousand Commandments.

Table 11. A Possible Breakdown of Economically Significant Rules

Disclosure can enable accountability. Congress routinely delegates legislative power to unelected agency personnel. Reining in off-budget regulatory costs can occur only when elected representatives are held responsible and end “regulation without representation.” Stringent limitations on delegation, such as requiring congressional approval of rules, are essential.

As detailed earlier, regulations fall into two broad classes: (a) those that are economically significant or major (with effects exceeding $100 million annually) and (b) those that are not. Agencies tend to emphasize reporting of economically significant or major rules, which OMB also highlights in its reports to Congress on regulatory costs and benefits. A problem with this approach is that many rules that technically come in below the threshold can still be very significant in real-world terms.

Under current policy, agencies need not specify whether any or all of their economically significant or major rules cost just above the $100 million threshold or far above it. One helpful reform would be for Congress to require agencies to break up their cost categories into tiers, for example, as depicted in Table 11. Agencies could classify their rules on the basis of either cost information that has been provided in the regulatory impact analyses that accompany some economically significant rules or separately performed internal or external estimates.

Abundant information about costs and burdens of regulation is available but scattered and difficult to compile or interpret. Online databases and sites like Regulations.gov now make it easier than it was back when interested citizens would need to comb through the Unified Agenda’s 1,000-plus pages of small, multicolumn print to learn about regulatory trends and acquire information on rules. Today it is easier to compile results from online searches and agencies’ regulatory plans, but more can be done. Material from the Unified Agenda could be made still more accessible, relevant, and user-friendly if elements of it were officially summarized in charts and presented as a section in the federal budget, in the Agenda itself, or in the Economic Report of the President. Suggested components of this Regulatory Transparency Report Card appear in Box 6.

In addition to revealing burdens, impacts, and trends, such a breakdown would reveal more clearly what we do not know about the regulatory state—such as, for example, the percentage of rules for which their issuing agencies failed to quantify either their costs or benefits. Observers lost what little ability existed to distinguish between rules that are additive and subtractive with regard to burdens upon the ejection of Executive Order 13771’s deregulatory designation and the fiscal year-end “Regulatory Reform Results” reports no longer available on OMB’s site. Similarly, future regulatory reforms should require regulatory and deregulatory actions to be classified separately in the Federal Register and for agencies’ confusing array of rule classifications to be harmonized.

The accumulation of regulatory guidance documents, memoranda, and other regulatory dark matter to implement or influence policy calls for greater disclosure than exists now, since these kinds of agency issuances can be regulatory in effect but are generally nowhere to be found in the Unified Agenda or Regulatory Plan. Inventorying such decrees is difficult, but formal attempts began in 2020 in response to Executive Order 13891 that are worth maintaining. Legislation such as the Guidance Out of Darkness Act (H.R. 1605, S. 628) could help address some of the shortcomings in guidance disclosure. In addition, current reporting distinguishes poorly between rules and guidance documents affecting the private sector and those affecting internal government operations.

Additional information could be incorporated as warranted—for example, success or failure of special initiatives such as executive branch restructuring (from Al Gore’s “Reinventing Government” under Clinton to Trump’s executive branch streamlining to Biden’s E.O. 14058 on “Transforming Federal Customer Experience and Service Delivery to Rebuild Trust in Government”) or updates on ongoing regulatory reform or disclosure campaigns. Providing historical tables for all elements of the regulatory enterprise would prove useful to scholars, third-party researchers, members of Congress, and the public. By making agency activity more explicit, a regulatory transparency report card would help ensure that policy makers take the growth of the administrative state seriously, or at least afford it the same weight as fiscal concerns.

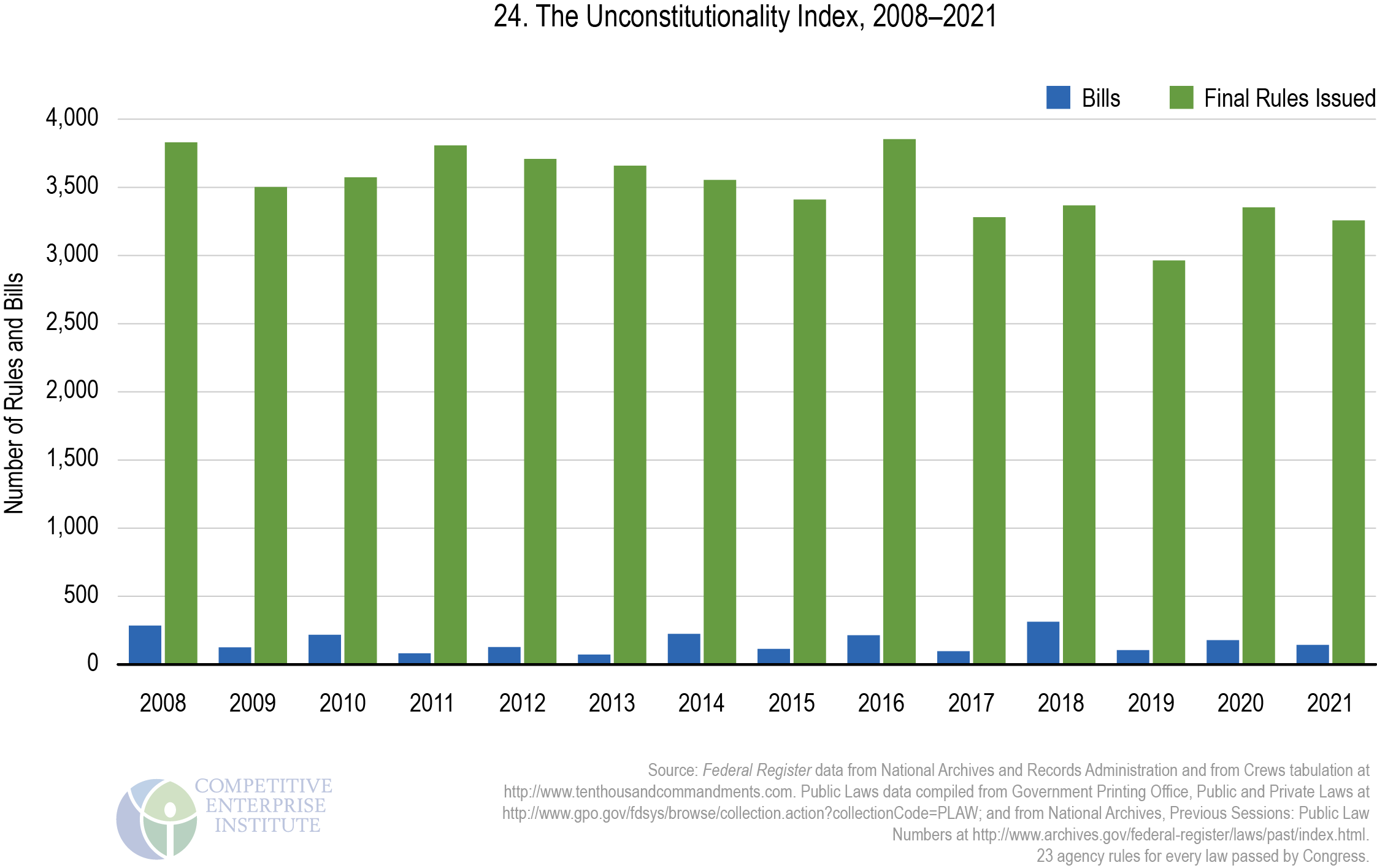

Ending Regulation without Representation: The “Unconstitutionality Index”—23 Rules for Every Law

Administrative agencies, rather than the elected Congress, do the bulk of U.S. lawmaking. Columbia University legal scholar Phillip Hamburger has described the rise of the modern administrative state as running counter to the Constitution, which “expressly bars the delegation of legislative power.” But agencies are not the primary offenders. For too long, Congress has shirked its constitutional duty to make the tough calls. Instead, it routinely delegates substantial lawmaking power to agencies and then fails to supervise them.

The primary measure of an agency’s productivity—other than the growth of its budget and number of employees—is the body of regulation it produces. Agencies face significant incentives to expand their turf by regulating even without genuine need. It is hard to blame agencies for carrying out the very regulating they were set up to do in the first place. Better to point a finger at Congress and restore accountability there.

The “Unconstitutionality Index” is the ratio of rules issued by agencies relative to laws passed by Congress and signed by the president. In calendar year 2021, federal regulatory agencies issued 3,257 final rules, whereas the 116th and 117th Congresses under Trump (in January 2021) and Biden secured passage into law a total of 143 bills (the corresponding figure in 2020 was 177 bills). That means nearly 23 rules were issued for every law passed in 2021 (there were 19 rules for every law in 2020; see Figure 24). There is overlap between Congresses in the calendar year depiction here. For example, the 143 laws enacted in 2021 included 62 signed by Trump.

The number of rules and laws can vary for many reasons, but the Unconstitutionality Index still provides some context about rules. The Unconstitutionality Index average over the past decade has been 26 rules issued for every law passed. However, in the context of Trump-era streamlining, the fact that eliminating a rule requires issuing a new one meant that the Index, ironically, grew because of deregulation. (Appendix: Historical Tables, Part I, depicts the “Unconstitutionality Index” dating back to 1993 and the number of executive orders and agency notices, which could arguably be incorporated into the Index.) Rules issued by agencies are not usually related to the current year’s laws; typically, agencies’ rules comprise the administration of prior years’ legislative measures.

Mounting debt and deficits, now at unprecedented peacetime levels, can incentivize Congress to enact regulatory legislation rather than to increase government spending to accomplish policy ends. Congress often relies on “must-pass” appropriations and reauthorizations to push through some initiatives, while the dedicated legislation it does pass—like the Affordable Care Act and Dodd-Frank financial reform law—spawn thousands of pages of regulations.

By regulating instead of spending, government can expand almost indefinitely without explicitly taxing anybody one extra penny. For example, if Congress wanted to boost job training, funding a program to do so would require legislative approval of a new appropriation for, say, the Department of Labor, which would appear in the federal budget and increase the deficit. As an alternative, one regulatory approach Washington could take would be to direct Fortune 500 companies to implement job training programs, to be carried out according to new regulations issued by the same Department of Labor. The latter option would add little to federal spending but would still let Congress take credit for the program.

Meanwhile, agency guidance documents and presidential directives now constitute a significant part of federal government activity. Such non-legislative policy making should be subject to greater disclosure.

An annual regulatory transparency report card is needed, but is not the complete response. Regulatory reforms that rely on agencies policing themselves within the limited restraints of the Administrative Procedure Act will not rein in the growth of the regulatory state or address the problem of regulation without representation. Rather, Congress should vote on agencies’ final rules before rules become binding on the public. Affirmation of new major and controversial regulations would ensure that Congress bears direct responsibility for every dollar of new regulatory costs.

The Regulations from the Executive in Need of Scrutiny Act (REINS) Act (H.R. 1776, S. 68, 117th Congress) offers one such approach. It would require Congress to vote to approve economically significant agency regulations. Versions have passed the House in previous Congresses, but have not moved forward in the Senate. To avoid getting bogged down in approving myriad agency rules, Congress could vote on agency regulations in bundles rather than individually. Another way to expedite the process is via congressional approval or disapproval of new regulations by voice vote rather than by tabulated roll-call vote. What matters most is that members of Congress go on record for the laws the public must heed.

If Congress does not act, states could step in. The Constitution provides for states to check federal power, and pressure from states could eventually prompt Congress to address regulation. Many state legislators have indicated support for the Regulation Freedom Amendment, which reads, in its entirety: “Whenever one quarter of the members of the U.S. House or the U.S. Senate transmit to the president their written declaration of opposition to a proposed federal regulation, it shall require a majority vote of the House and Senate to adopt that regulation.” That amounts to an impelled version of the REINS Act for the rule in question. Congressional—rather than agency—approval of regulatory laws and their costs should be the main goal of reform, along with reassessment of bounds on the exercise of power by Congress in modern times.

When Congress ensures transparency and disclosure and finally assumes responsibility for the growth of the regulatory state, the resulting system will be one that is fairer and more accountable to voters. Legislative reform of regulatory processes and executive branch streamlining are parts of more fundamental debates. Congress is responsible for the fiscal budget, yet deficits remain the norm. The larger questions are over the role and legitimacy of the administrative state and the role of government in a constitutional republic.