The compliance crisis: Unveiling the regulatory loopholes agencies love

Photo Credit: Getty

While federal regulatory reform is critical, it’s equally important that existing oversight laws be followed. Unfortunately, many of these laws are routinely disregarded, with little consequence.

We at CEI often point to the fact that no one really knows how many federal agencies exist. A new report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) emphasizes a related problem: we also don’t know how many federal spending programs exist either, despite a 2011 law requiring a comprehensive inventory from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Recent national defense authorization legislation, GAO notes, has given OMB until January 2025 to comply.

We also often point to a growing fusion between spending and regulation, so this lapse by OMB is troublesome to say the least. Unfortunately, skepticism is warranted with respect to the thoroughness of OMB’s upcoming inventory. OMB’s track record on compliance with regulatory oversight laws is also poor, as I detail in a new column at Forbes, and Congress has been largely indifferent to holding them accountable. Consider the following:

The Regulatory Right-to-Know Act mandates an annual report to Congress on the benefits and costs of major rules. However, these reports are consistently overdue and incomplete. The most recent, covering fiscal years 2020-22, was published in early 2024. Most glaringly, the requirement for an aggregate cost estimate for federal regulations have been ignored since the early 2000s, leaving little transparency about the cumulative burden of the administrative state.

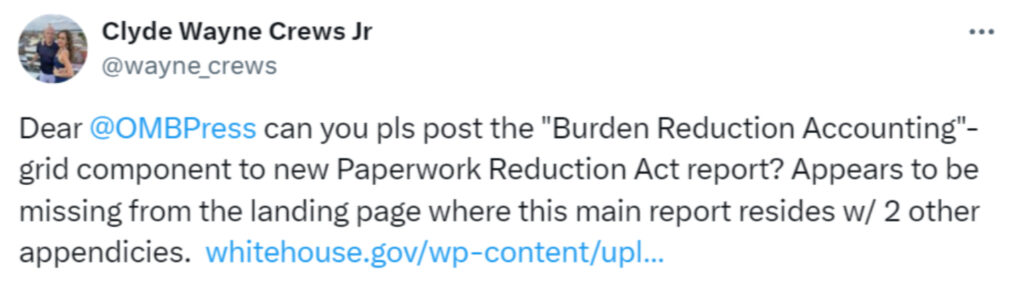

The Paperwork Reduction Act also suffers from neglect. The Information Collection Budget (ICB) required by the Act has been sporadically published in recent years, with several delayed editions appearing in 2023. The latest ICB shifts focus away from reducing paperwork burdens toward increasing access to government benefits (of the very sort OMB neglects to thoroughly inventory, conveniently enough)—neglecting its original purpose. Additionally, the annual “Paperwork Burden Accounting” roundup, which traditionally documented over 10 billion hours of paperwork, is conspicuously absent from the latest edition. We did inquire, but it remains unaddressed:

The Regulatory Flexibility Act (RFA), intended to ease small business burdens, is also often ignored. A 2024 report from the House Small Business Committee found that agencies frequently misclassify rules to bypass RFA analysis and underestimate the impact on small businesses. They also fail to assess whether new rules duplicate existing regulations, resulting in unnecessary burdens.

The Congressional Review Act, designed to give Congress a window to review and disapprove major rules, is also underutilized. Despite thousands of rules being issued since its passage, fewer than two dozen have been overturned. But elements of it are also unlawfully disregarded. Some major rules are not properly submitted to GAO and to both houses of Congress, which raises questions about their validity.

There are a couple recent laws that could improve matters that I discuss in the Forbes article, such a 2023 law that Biden signed requiring 100-word summaries to accompany rules in the Federal Register, and one just signed this month (the GAO Database Modernization Act, to supplement GAO’s database by requiring agencies to notify GAO whenever a rule is revoked, suspended, replaced, amended, or otherwise made ineffective.

These two developments represent a silver lining on a dark regulatory cloud. Congress needs to remain vigilant that they do not lapse in the manner of their predecessors. Addressing widespread noncompliance with regulatory oversight laws should be a priority in the coming months and years as the 118th Congress enters its final weeks.

For more, see Forbes, “Exposing Loopholes: How Federal Regulatory Oversight Laws Are Being Ignored.”