EPA’s latest unlawful assault on vehicle affordability and choice

Photo Credit: Getty

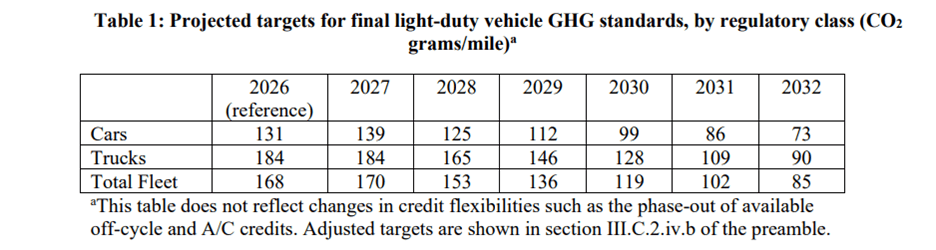

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) today announced final emission standards for passenger cars, light-duty trucks, and medium-duty vehicles for model years 2027 through 2032 and later. The pre-Federal Register draft of the rule, all 1,181 glorious pages, is available here. The rule sets standards for both conventional air pollutants and greenhouse gases (GHGs).

The EPA’s press release crows that the rule will “expand consumer choice in clean vehicles.” That’s a little like saying prohibiting the sale of alcoholic beverages will expand consumer choice in soft drinks.

The fact is, the EPA is waging war on vehicle affordability and choice. As has often been said, truth is the first casualty in war. When the EPA proposed this rule in May 2023, it stated that, unlike California’s zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) sales mandate, “the GHG program in this proposal is performance-based and not a ZEV mandate.” However, like the California program, the EPA program compels automakers to manufacture and sell increasing percentages of electric vehicles (EVs), only at a somewhat slower pace. It is a de facto EV mandate.

That is easily demonstrated. Toyota’s most fuel-efficient Prius hybrid, which is also the world’s top-selling hybrid, gets 57 miles to the gallon and emits 155 grams of carbon dioxide per mile (CO2/mi), according to fueleconomy.gov. Toyota also sells several other hybrids and non-hybrids with lower mileage and higher CO2 emission rates. But even if Toyota scrapped all those models, and just sold Priuses, the company’s fleet-average CO2 emissions per mile would still be more than double the standard that the EPA has set for model year 2032 passenger cars—73 grams of CO2/mile.

Clearly, automakers cannot comply with the EPA’s allegedly “technology-neutral” and performance-based GHG program without rapidly phasing out sales of gasoline- and diesel-powered vehicles, including fuel-efficient hybrids, and rapidly ramping up sales of EVs.

EVs have several well-known drawbacks compared to comparable internal combustion engine cars. EVs cost more. They have inferior range. Recharging an EV takes much longer than filling up a gas tank. There are far fewer recharging stations than gas stations.

Due to those and other issues, unsold EVs are piling up on dealer lots. In November 2023, 4,000 auto dealers urged President Biden to “tap the brakes” on his vehicle electrification agenda. Despite “deep price cuts, manufacturer incentives, and generous government incentives,” the dealers noted, EVs “are not selling nearly as fast as they are arriving at our dealerships.” “With each passing day,” they stated, “it becomes more apparent that this attempted electric vehicle mandate is unrealistic based on current and forecasted customer demand.”

As if that were not bad enough, Ford Motor Company lost $4.7 billion on its EV program in 2023. As energy analyst Robert Bryce reports, that means Ford lost $64,731 for every EV it sold.

It is no wonder then, that the EPA decided to relax somewhat the tailpipe CO2 standards for model year 2027-2030 vehicles. But in 2032 the standards for passenger cars still end up at 73 grams CO2/mi, and the standards for light-trucks and combined fleet (passenger cars + light trucks) are virtually identical to the standards in the EPA’s May 2023 proposed rule.

Proposed vs. Final tailpipe GHG standards

Cars Trucks Combined

Proposed Final Proposed Final Proposed Final

| 2027 | 134 | 139 | 163 | 184 | 152 | 170 |

| 2028 | 116 | 125 | 142 | 165 | 131 | 153 |

| 2029 | 99 | 112 | 120 | 146 | 111 | 136 |

| 2030 | 91 | 99 | 110 | 128 | 102 | 119 |

| 2031 | 82 | 96 | 100 | 109 | 93 | 102 |

| 2032 | 73 | 73 | 89 | 90 | 82 | 85 |

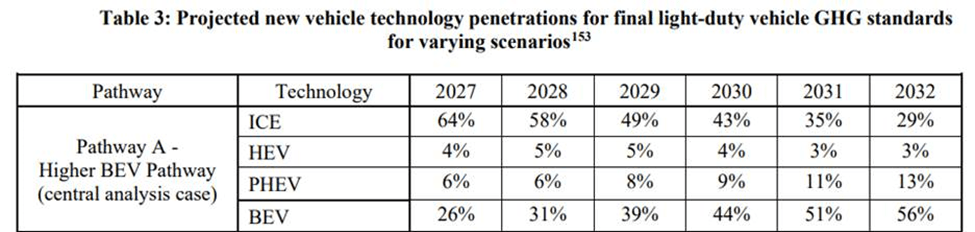

Although slightly less stringent than the proposed standards, the final standards drive approximately the same level of vehicle electrification.

“The moral of the story,” my colleague Daren Bakst observes, “is that almost 70 percent of new cars and light trucks will be plug-in electric vehicles, and less than 30 percent of new light-duty sales will be internal combustion engine vehicles.”

The good news is that, legally, the EPA is cruising for a bruising. The final rule flagrantly flouts the Supreme Court’s ruling in West Virginia v. EPA (2022), which vacated the agency’s so-called Clean Power Plan. Whether gasoline- and diesel-powered cars should be banned is a major question of national policy. Whether the EPA should wield the powers of an industrial policy czar for the automotive sector is a major question of national policy. Neither Section 202 of the Clean Air Act nor any other provision of law expressly authorizes the EPA to phase out internal combustion engine vehicle sales or restructure the automotive sector. The EPA’s rule is unlawful and merits prompt review by the Supreme Court.