NHTSA’s proposed fuel economy reset: Putting consumers in the driver’s seat

Photo Credit: Getty

On Wednesday, I submitted comments in support of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s (NHTSA) proposed Safer Affordable Fuel Efficient (SAFE) Vehicles Rule III. SAFE III would significantly reduce the stringency of Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards. In turn, it would reduce manufacturer compliance burdens, enhance US auto industry competitiveness, promote consumer choice, and avert an estimated $900 increase in average new car prices.

Better still, SAFE III would clarify and enforce Section 32902(h) of the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA). Section 32902(h) prohibits NHTSA from setting CAFE standards that would rig the market in favor of electric vehicles (EVs) and other “dedicated automobiles” and against automobiles that operate chiefly or solely on gasoline or diesel fuel.

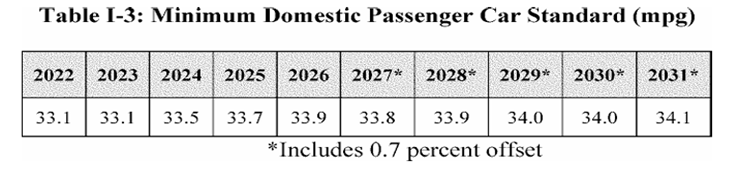

Consider the proposed changes in regulatory stringency. Here are the current CAFE standards promulgated by the Biden NHTSA in June 2024:

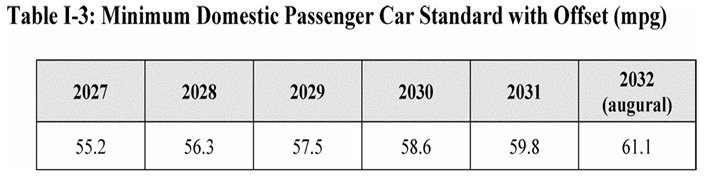

Here are SAFE III’s proposed standards:

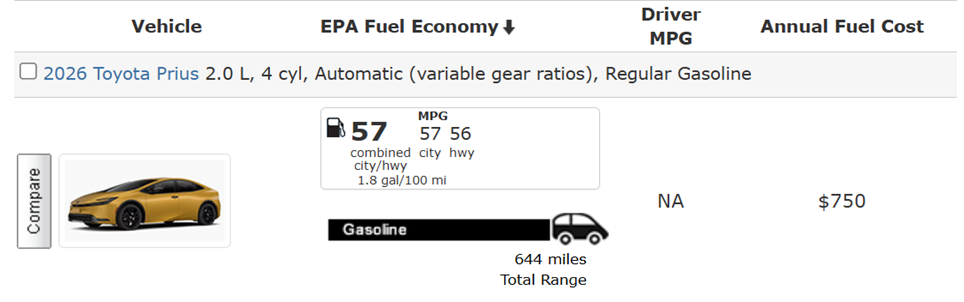

Perhaps the easiest way to see the problem with the Biden-era NHTSA standards is to compare them to the fuel economy of Toyota’s best-performing Prius hybrid.

Keep in mind that CAFE standards are fleet-average requirements, and that Toyota also manufactures hybrids and non-hybrids with lower mpg ratings, such as the Crown Hybrid AWD, rated at 41 mpg, and the non-hybrid Corolla (1-mode TM), rated at 35 mpg. Even if all Toyota passenger cars achieved the mpg of the Prius hybrid shown above, the fleet average would fall short of the current standards for model years 2029-2032.

How, then, can legacy automakers comply? They can sell more battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHEVs) and fewer internal combustion engine vehicles. They can also purchase CAFE compliance credits from full-time EV companies, which “earn” large numbers of credits for each EV sold. In other words, legacy automakers can comply by conferring billion-dollar windfall profits on Tesla.

This pressure to either produce and sell EVs or subsidize EV makers is exactly the sort of market-distorting compulsion EPCA § 32902(h) was intended to prevent. But first, some quick background on the CAFE standard-setting process.

A related provision, EPCA § 32902(f), requires NHTSA to set fuel economy standards at the “maximum feasible” level. To determine what that level is for each class of vehicles in each model year, NHTSA weighs and balances four statutory factors: technological feasibility, economic practicability, the effect of other federal vehicle standards on fuel economy, and the nation’s need to conserve energy. The weight NHTSA assigns to those factors may vary as circumstances change. For example, when US oil production is high and gasoline prices are low, there is less need to conserve energy than under the reverse conditions.

EPCA § 32902(h) states that when determining what levels of CAFE standards are the maximum feasible, NHTSA ‘‘(1) may not consider the fuel economy of dedicated automobiles [such as BEVs]; (2) shall consider dual fueled automobiles [such as PHEVs] to be operated only on gasoline or diesel fuel; and (3) may not consider, when prescribing a fuel economy standard, the trading, transferring, or availability of credits under section 32903.”

How did the Biden NHTSA evade those strictures? Since 2012, NHTSA has construed the statute “narrowly,” which really means it has construed it loosely. Under loose construction, the fleet average fuel economy “baseline” NHTSA uses to calculate maximum feasible levels may reflect the projected market share of dedicated automobiles due to factors other than CAFE standards, such as California’s zero-emission vehicle mandates and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) motor vehicle greenhouse gas (GHG) emission standards, which implicitly regulate fuel economy. The baseline may also reflect the availability of CAFE credits in model years before and after the period for which NHTSA is setting standards.

Those interpretations inflated the apparent affordability and feasibility of aggressive CAFE standards — even those exceeding the technical limits of gasoline- and diesel-powered cars.

SAFE III would put an end to such mischief. As SAFE III states, the restrictions in EPCA § 32902(h) are “unequivocal” and the prohibition against considering the market share of alternative fueled vehicles is also “clear” from the legislative history. See former Rep. John Dingell’s (D-MI) floor statement on the House and Senate’s passage of the provision.

In short, in SAFE III, NHTSA determines that CAFE standards “must be feasible and practicable” for gasoline- and diesel-powered vehicles without “any reliance” on alternative-fueled vehicles or compliance credits.

NHTSA also proposes to eliminate the inter-manufacturer credit trading system, starting in model year 2028. Legacy manufacturers would no longer need the flexibility provided by credit trading, because they would no longer be subject to onerous standards. Manufacturers would be able to focus more on satisfying consumers and less on navigating regulatory complexities.

Thanks to the Trump administration and Congress, America is on the cusp of liberating the US auto industry from decades of overregulation. Congress and President Trump repealed the waiver for California’s Advanced Clean Cars II program, which would prohibit in-state sales of new gasoline- and diesel-powered cars by 2035. EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin has proposed to repeal the EPA’s motor vehicle GHG standards, which increasingly function as de-facto EV mandates. Now, with SAFE III, NHTSA proposes to terminate and preclude the agency’s unauthorized participation in forced vehicle electrification.

If all goes according to plan, America can look forward to an era of more affordable automobiles, more choices for consumers, and a more competitive auto industry.