Trump Regulatory Reform Agenda By the Numbers: End of One-In, Two-Out?

The Trump administration has released the Fall 2019 edition of the twice-yearly Unified Agenda of Federal Regulatory and Deregulatory Actions.

Around since the early 80s, the blockbuster Unified Agenda updates an excited world about regulatory priorities of the federal bureaucracy.

Actually it bores people, but Trump’s regulatory cuts and liberalization agenda have distinguished versions of the beefy report up to this point, with the administration boasting that agencies continue to meet Trump’s requirement (initiated in Executive Order 13771 on Reducing Regulation and Controlling Regulatory Costs) to eliminate two significant regulations for every new one added, and maintain net-zero new costs.

The Agenda has long revealed regulatory priorities of the federal regulatory bureaucracy, however, and Trump’s emphasis on reviewing the inventory for cuts—its new deregulatory character—has been unique.

Released last year on October 23 with more fanfare, the Agenda was not accompanied this time by a regulatory reform results update on the status of the “one-in, two-out” directive and whether there has been continued success by the administration in maintaining the pace. (here’s FY2018’s)

We’d always said it was getting tougher.

In fiscal year-end 2017, the Administratin claimed a rules-out to rules-in ratio 22-to-1 (yes, criticisms abounded). The ratio for significant regulatory actions in 2018 was four-to-one, with 14 significant new regulatory actions and 57 significant deregulatory ones (the overall count had been 176 deregulatory actions and 14 significant regulatory actions, for an overall ratio of 12 to one). In the first year, additional eliminations of rules not officially considered “significant,” as well as eliminations of agency guidance documents argued to have regulatory effect also took place (guidance documents are a category for which the Administration recently issued new executive orders).

The Agenda landing page now states that “Fulfilling longstanding principles to review and assess existing regulations, the Agenda includes new deregulatory actions, as well as the withdrawal and reconsideration of other regulatory actions,” but it doesn’t breathlessly detail deregulatory moves swamping regulatory ones.

So we’ll assess that here.

Overall, the new Agenda shows that agencies have 3,752 rules in in the pipeline (at the active, completed, and long-term phases), compared to 3,209 in fall 2017. A comparison of Trump’s tenure with former President Barack Obama’s final Unified Agenda, appears here:

Trump’s total flow for the past two years exceed Obama’s exit total and sets his own record. An important difference, however, is items classified “deregulatory,” via the “E.O. 13771 Designation,” a reporting innovation under Trump. Rule counts remain in the several thousands, but a deregulatory measure also counts as a “rule,” which confuses things. Many rules of course are routine safety directives from bodies like the Federal Aviation Administration and Coast Guard rather than new initiatives.

Last year—in fall 2018—there was a total of 671 of these “deregulatory” rules among the 3,534 total, for a “net” of 2,863.

This time around the overall “deregulatory” count is 689; a similar number to last year, but with more rules overall, a “net” of 3,063. The Environmental Protection Agency has separately reported today that its section of the Agenda “includes 56 actions that are expected to be deregulatory and 37 actions appearing for the first time.” It does not give an explicit ratio, however it maintains its own running web tally, as some other agencies do.

The administration has emphasized “significant rulemakings” in its year-end two-for-one updates. The Unified Agenda presents a similar subset of all rules classified as “economically significant,” loosely meaning they have $100 million in effects. Here’s how recent years compare with the new fall Agenda:

Other specifics regarding E.O. 13771 deregulatory actions via “E.O. 13771 Designation” in the database now include radio-button selection options for each of the following:

- Deregulatory

- Regulatory

- Fully or Partially Exempt

- Not subject to, not significant

- Other

- Independent agency

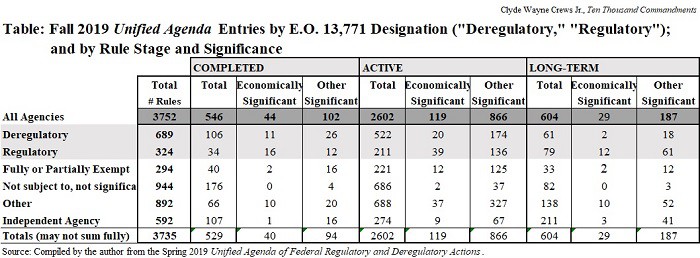

So to get a better look at the two-for-one results, it is helpful to look separately at a grid of “completed,” “active,” and “long-term” rule categories in the aggregate as well as split up into “economically significant” and “other significant” components. This is done in the table below:

As the table shows in the grey-highlighted area, overall there are 689 “deregulatory” actions and 324 “regulatory” ones in the fall update pipeline; this means a broad ratio of just a bit over two-to-one is met taking the entire flow and recently completed inventory into account.

However we don’t necessarily know what all the “other,” “not subject to” and “partially exempt” are really getting at or referring to — and there are thousands of them. This could be something of a red flag since the bulk of the administrative state’s rules get placed in these categories. These classifications, as well as agency guidance documents, need audit.

Completed Rules No Longer Meet Trump’s Two for One Directive in a Technical Sense, But It’s Always Been Getting Tougher

For recently Completed rules, the counts are 106 Deregulatory and 34 Regulatory, for a seemingly still healthy ratio of 3.1-to-one. Likewise, in the “active” (pre-rule, proposed, and final) category, there are 522 “deregulatory” and 211 “regulatory” actions in the pipeline, for a 2.5-to-one ratio. The table depicts both of these elements.

The E.O. 13771 directive applies to “significant” rules, however, so let’s see where things stands now for completed significant rules.

As the table details, of the 106 completed “deregulatory” actions in the Fall 2019 Agenda, just 11 are in the “economically significant” category. Twenty-six completed deregulatory rules in the table are deemed “other significant.” As for “regulatory” actions, 34 completed ones appear in the Spring Agenda, with 16 of them deemed “economically significant” and 12 “other significant.”

So there are 37 significant deregulatory actions overall, but also 28 significant regulatory ones. The ratio here does not meet the required one-in-two out criterion as it has in past fiscal year-end updates.

Increasingly, “significant” actions appear to be getting overwhelmed, such that enlisting other deregulatory but not significant measures will be needed to make the ratios work. That move is still acceptable as far as the executive order’s no-net-cost mandate is concerned, but troubling if one’s hope was rollback of the administrative state.

Significant “Active” Deregulatory and Regulatory Actions Need Attention to Make 2-for-1 Work Again

Active actions—those sitting in the pipeline at the “pre-rule,” “proposed,” and “final” rule stages—might be thought of as rules in the production process. The table above shows that a total of 522 deregulatory “active” actions in play well exceed 211 regulatory ones, for a 2.5-to-one margin overall when non-significant rules are included.

As non-completed actions, these rules are not obligated at this point to meet the two-for-one goals, but they might be regarded a leading indicator.

Of more concern are the costlier subsets of active rules. There are 39 economically significant regulatory actions in the table, but only 20 economically significant deregulatory actions in play, potentially putting two for one on a path to being inverted, not just unmet. In the “other significant” category, 136 regulatory actions are outweighed by 174 deregulatory ones, but not by a factor of two-to-one. Since active rules encompass both proposed and final undertakings, there is time to course-correct as rules in the pipeline move closer toward finalization.

Warning Signs: “Long-term” Planned Regulatory Actions Greatly Outstrip Deregulatory Ones

The “Long-term” rules category makes the concern over the longevity of one-in, two out even clearer. Here, agencies unabashedly show they plan more regulating than deregulating. At the moment, agencies anticipate 79 “regulatory” actions but only 61 “deregulatory” ones, and the situation is far worse for the costlier “economically significant” and “significant” subsets.

The fact that only two economically significant long-term deregulatory actions are listed as planned this deep into Trump’s term is a concern. By contrast, 12 economically significant regulatory actions are planned. “Other significant” long-term regulatory actions also exceed deregulatory ones by more than 3-to-1. How will those be offset?

These are warning signs because the more costly rule subsets are presumably where tomorrow’s cost savings need to come from. The “long-term” category in particular illustrates how regulatory liberalization will require congressional action, but Democrats have no interest in working with Trump on any of this, of course.

What next? Trump’s two-for-one policy does not cover every part of the regulatory apparatus. It doesn’t apply, for example, to “non-significant” rules nor to rules mandated by Congress (as opposed to those agencies self-generate) although agencies have been reducing these. It also does not apply to the so-called independent agencies like the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) or the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). Regulatory liberalization measures can exceed what we see just in the Unified Agenda. It can include some rollbacks of guidance documents, which do not generally appear in the Unified Agenda, in addition to formal rules. These need to be better accounted for to get a more complete picture of what the administration is doing, and to that end, there will now be more formal roundups of those informal documents too, because without a similar “status report” like what Trump has given us for two-for-one and for caps, we miss their impact.

I have noted before that the Trump reforms have not changed the fundamental regulatory impulses of the bureaucracy. Agencies like the FCC, the CFPB, and the Environmental Protection Agency have shifted gears under pressure from the current administration; but the increase in deregulatory actions will be transitory unless Congress enacts longer-term regulatory reform, and unless guidance documents are addressed.