United Kingdom Invokes Article 50 to Leave the European Union

In a historic moment, British Prime Minister Theresa May today invoked Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union, which formally starts the process of Britain leaving the bloc. Her Majesty’s Government has announced plans to fold all of existing EU law into British law as part of the process, to be included in the Great Repeal Bill, which will be published on Thursday.

In a historic moment, British Prime Minister Theresa May today invoked Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union, which formally starts the process of Britain leaving the bloc. Her Majesty’s Government has announced plans to fold all of existing EU law into British law as part of the process, to be included in the Great Repeal Bill, which will be published on Thursday.

The Great Repeal Bill will begin what may prove the greatest deregulatory endeavor undertaken by any modern government. Some 19,000 pieces of EU law will have to be translated into a form compatible with Britain being outside the EU, and then Parliament and government will have to work together to deliver the promise of freedom from bureaucracy that was an important part of many people’s decision to vote to leave the EU.

How they will do it remains to be seen, but last year Rory Broomfield of The Freedom Association and I suggested that a Royal Commission on Regulatory Reduction would be appropriate in our book, “Cutting the Gordian Knot.”

We also outlined the Article 50 process and some potential questions surrounding it as follows.

Article 50 of the Treaties on European Union states:

A Member State which decides to withdraw shall notify the European Council of its intention. In the light of the guidelines provided by the European Council, the Union shall negotiate and conclude an agreement with that State, setting out the arrangements for its withdrawal, taking account of the framework for its future relationship with the Union. … It shall be concluded on behalf of the Union by the Council, acting by a qualified majority, after obtaining the consent of the European Parliament.

Article 50 has never been tested. As a result, there is considerable uncertainty over how it will apply. The EU’s executive body, the European Commission, has no formal role in the process. Negotiations are conducted by the European Council (the “Senate” of member states) after obtaining the consent of the European Parliament. …

Assuming the Parliament grants consent, the negotiations will need to be conducted in light of the fact that Article 50 assumes the “end of the application of the Treaties and the Protocols thereto in the state concerned from that point on.” Therefore, Article 50 negotiations will need to cover such things as the phasing out of various EU programs, such as the diverse forms of EU financial aid. Other topics of discussion likely will include transitional arrangements for trade with third parties covered by EU agreements and the future of the UK’s trade arrangements with the EU itself. However, the most important aspect of the negotiation for many people will be the status of UK and EU citizens resident in the others’ jurisdiction. [This remains the case – an attempt by PM May to secure reciprocal rights in advance of the negotiations was rebuffed by German Chancellor Angela Merkel.]

Under Article 50, if no agreement on these matters is reached by the end of a period of two years after the invocation of the article (which can be extended), then the UK will simply cease to be a member of the EU and could be considered to have been kicked out, with no special arrangements for its future relationship.

Whatever happens, March 29, 2017 will be remembered as one of the most important dates in British history, the start of what may prove to be an astonishing act of regulatory liberalization. If Britain begins to strike new forms of trade deals based around mutual recognition, it may also prove to be the beginning of a new order for global trade.

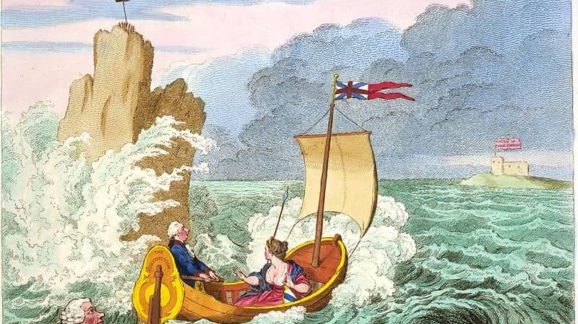

The cover of our book shows Pitt the Younger and his companion Britannia sailing his ship, The Constitution, between the Scylla of populism and the Charybdis of autocracy to the haven of Liberty. If Britain is to survive her journey through Article 50, her ancient liberal constitutional order will be needed as much now as ever before.