Chapter 2: Why we need a regulatory budget

Well before Biden’s unique transformations, policymakers recognized a role for regulatory restraint, transparency, and disclosure. Federal programs are funded either by taxes or by borrowing, with interest, from future tax collections. That disclosure is elemental to holding representatives accountable for spending, plus the public can readily inspect the costs of programs and agencies in Congressional Budget Office publications and in a formal federal budget with historical tables.

Regulation is different. Although spending and regulation are both mechanisms by which governments act or even compel, the costs of regulation are less transparent and less disciplined. That means Congress might sometimes find it attractive to act via off-budget regulation rather than spending or raising taxes. And even when regulatory compliance costs do prove burdensome and attract criticism, Congress can escape accountability by blaming agencies.

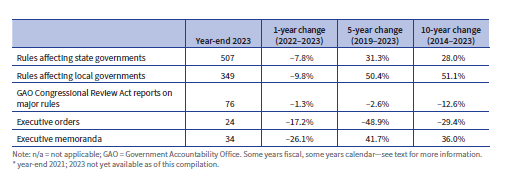

Granted, disclosure of federal spending obviously has not restrained deficits and runaway debt. Yet transparency is vital for wrestling the budget back under control. In similar fashion, policymakers should publicly disclose regulatory costs, burdens, and vital information to the fullest extent possible despite leadership that is more open to a carbon budget than a regulatory one. Table 1 provides an overview of the 2023 federal regulatory enterprise discussed in the following pages, as well as a flavor of the kinds of components to embed in a “regulatory report card” and transparency that should come from officialdom.

About our $2.1 trillion estimate

A regulatory budget would be a great idea to keep Congress and the executive branch honest about the costs they are offloading to the private sector. However, the reality is that total regulatory costs are immeasurable, often unfathomed, and have not and cannot be truly calculated. It has been a quarter century since the federal government even tried.

There are no objective metrics to assess, apart from raw outlays on the likes of equipment and personnel. The subjective and internally felt opportunity costs of regulation cannot be calculated by an outsider any more than economies can be centrally planned. Make no mistake: there is no agreement on the costs and benefits of regulation, whether individually or in the aggregate, and there never will be.

Nonetheless, demanding some aggregate regulatory cost baseline is a reasonable ask of officialdom. In the wake of Biden’s Executive Order 14094 on modernizing regulatory review, the official narrative in large part denies that interventions are costs at all, and it makes questionable claims of savings, such as the White House assertion that water heater regulation and forced replacement are “going to help consumers save about $11 billion a year.”

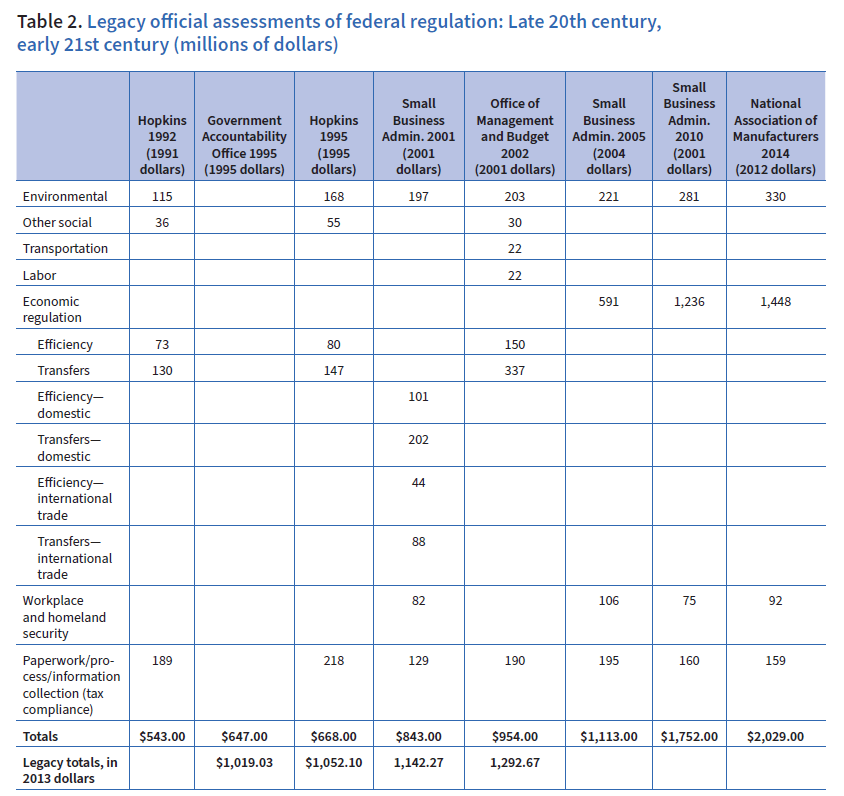

For purposes of maintaining a conservative accounting, Ten Thousand Commandments has employed a roughly $2 trillion estimate annually for years. This approach is based largely but not entirely on the federal government’s own reckonings that emerged from the mid- to late 1990s reform era encompassing compliance costs, economic and gross domestic product (GDP) losses, and social and other costs, supplemented with irregular White House updates of select costs and benefits.

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) estimate of $954 billion in 2002 (in 2001 dollars) would translate to over $1.64 trillion now. Of course, a lot has happed since then, including the addition of such rulemaking engines as the Department of Homeland Security, the Dodd-Frank financial law, the Affordable Care Act, federal pushes against fossil fuels and functional household appliances, and more.

The recent four years of lockdown, infrastructure, inflation, and technology spending and control constitute a marked channeling of private-sector resources and energies toward government-chosen ends via direct spending, contracting, procurement, and attendant regulation, all capable of compound ripple effects that, like most regulation, go unquantified.

Notable examples include the Federal Communications Commission’s 2023–2024 resurrection of its net neutrality campaign, as well as broadband social-policy schemes, in particular the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA)-rooted rule on “Prevention and Elimination of Digital Discrimination” and its build-out mandates and price controls. Similar IIJA-rooted digital-welfare campaigns stem from the Commerce Department’s National Telecommunications and Information Administration that—alongside endorsing FCC in its “digital discrimination” regulatory proceeding—boasts its own haphazard allocation of over $42 billion in BEAD (Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment) funding with social agenda strings not contained in the IIJA legislation itself.

A new National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) report, titled The Cost of Federal Regulation to the U.S. Economy, Manufacturing and Small Business, finds regulatory costs of $3.079 trillion for 2022 (in 2023 dollars). Employing bottom-up approaches and top-down regression modeling rooted in “academic literature finding that macroeconomic performance and living standards are systematically linked to regulatory policies,” the NAM assesses regulatory costs this way:

- Economic: $2.067 trillion

- Environmental: $588 billion

- Occupational safety/heath and homeland security: $124 billion

- Tax compliance: $300 billion

According to the report, the $2 trillion economic component encompasses rules affecting decision-making in, for example, “markets for final goods and services, markets for physical and human resources, credit markets and markets for the transport and delivery of products and factors of production.” Such interventions “affect who can produce, what can (or cannot) be produced, how to produce, where to produce, where to sell, input and product pricing and what product information must be or cannot be provided.”

Direct compliance outlays by firms, which understate the whole, include “investments in capital equipment, expenditures on O&M [operations and maintenance], payments to outside consultants, in-house employees devoted to compliance activities and so forth.” For reference, the last column of Table 2 also depicts the NAM’s 2014 estimate of $2.029 trillion.

Other assessments in recent years find regulatory costs even higher than the NAM’s new reckoning. Others look at components. For example, a report using 2002–2014 data on occupational tasks and firms’ wage spending finds that the “average US firm spends between 1.3 and 3.3 percent of its total wage bill on regulatory compliance” and that the “wage bill devoted to regulatory compliance workers in 2014 was between $79 billion and $239 billion, depending on the stringency of the regulatory compliance measure, and up to $289 billion when equipment is included.”

In law but not in practice, the primary official reckoning citizens receive regarding the scale and scope of regulatory costs is a would-be annual OMB survey of a subset of regulatory costs and benefits, the Report to Congress on the Benefits and Costs of Federal Regulations and Agency Compliance with the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act. The report invokes the Regulatory Right-to-Know Act, but the mandatory aggregate reports that law requires have not appeared in two decades. Those had been replaced by a 10-year lookback (thereby conveniently omitting the first years of the 21st century and the entire 20th), which has itself lapsed despite the nearly unlimited resources at the federal government’s command.

In 2023, the White House released three catch-up draft editions of the Report to Congress in a

composite format encompassing fiscal years 2020–2022. FY 2023 has yet to appear. Table 3 depicts 270 major rules over the period reviewed, compared with 9,778 rules—from large to inconsequential—finalized in the Federal Register during the same time frame. Like its predecessors, the Report to Congress contains a limited overview of executive agency major rules and partial monetary quantification of some costs and benefits. Only 31 major rules featured both benefits and costs quantified and monetized. This category is what administrations typically point to when touting net benefits of the regulatory enterprise. However, another 56 major rules had costs alone quantified, which historically OMB does not sum up. Although the Report covers agencies’ compliance with the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act, the independent agencies, which include formidable regulators such as the FCC and financial regulatory bodies, are exempt from OMB cost–benefit review. Overall, as Table 3 also shows, about 32 percent of the reviewed major rule subset features quantitative cost estimates. Beyond the designated major rules, the proportion of rules with cost analysis averages less than 1 percent.

The 2022 edition of Ten Thousand Commandments employed an estimate of $1.927 trillion for annual regulatory costs that had incorporated OMB Report(s) to Congress through FY 2019, making it a touch-point of sorts now for the first two decades of the 21st century and the incremental costs that OMB is now revealing.

As Table 3 also shows, the first three years of the 2020s had 31 rules with both benefits and costs quantified, adding $13 billion to annual regulatory costs. The inventory of what those rules are is presented in Appendix A, among which are familiar examples like vehicle fuel efficiency, building energy conservation, and industrial admissions standards, as well as the presence of the then deregulatory Trump-era moves on “waters of the United States.” That $13 billion was added during this time frame, when the first two of the three fiscal years represented Trump savings, and is noteworthy, given that the first 20 years of the century found OMB noting $151 billion in annual costs added, averaging around $7 billion annually. Although not a trend, increasing rule costs that policymakers might monitor are indicated.

The 56 rules noted in Table 3’s fourth column with costs alone quantified were also impactful, adding $46 billion to ongoing annual costs. Appendix B details these rules for fiscal years 2020–2023, some of which have also been prominent, such as COVID-19 paid leave. Going back to 2002, there are dozens of such cost-only rule disclosures, with high-end cost estimates that totaled $53.71 billion. Notably, the first three years of this decade alone have added nearly that amount, indicative yet again of rulemaking costs on the rise.

To this incremental $59 billion in quantified rules of 2020–2023 from the Report to Congress, we might also incorporate a small annual paperwork cost component for independent agencies. In addition to the tardy composite Report to Congress, five laggard Information Collection Budget of the U.S. Government volumes appeared in belated compliance with the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1980. The FY 2022 component reported that 10.34 billion hours were required to complete mandatory paperwork from 40 departments, agencies, and commissions. Paperwork is also tracked online: as of January 22, 2023, OMB’s website reported that government-wide totals for “Active Information Collections” imposed a “total annual cost” of $143,731,031,418 and take up 10,419,273,111.45 hours. One might note with amusement the $418 and the three-quarters-of-an-hour precision on time consumed.

The 10.34 billion hours Washington says it takes to complete federal paperwork in its Information Collection Budget snapshot translates into the equivalent of 14,883 human lifetimes. For our purposes, executive branch agencies’ paperwork costs are assumed to have been incorporated into the Report to Congress. However, since independent agencies’ costs are not, the release of paperwork reports allows the incorporation of a small amount of incremental costs here. Assuming $35 per hour, costs that were $22.14 billion at the time of the 2022 Ten Thousand Commandments now stand at $28.05 billion. Interestingly, in keeping with the OMB shift from regulatory streamlining to greasing the pursuit of net benefits, the new Information Collection Budget is packaged as “Tackling the Time Tax,” wherein the thrust is not reducing paperwork burdens on the regulated public but increased access to taxpayer-provided benefits via the likes of automatic eligibilities and partnerships with community-based organizations.

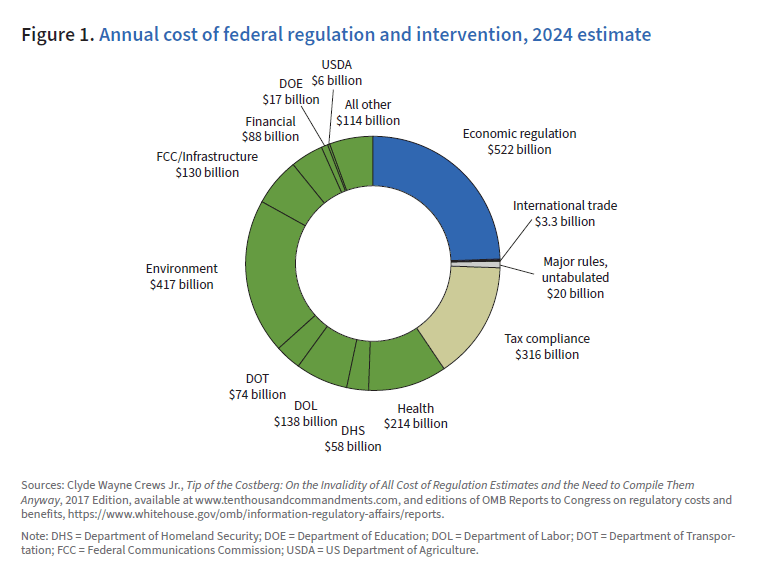

The paperwork cost increment plus the $59 billion Report to Congress addition brings our placeholder for the cost of regulation to $1.993 trillion. To this—particularly given the context and framing of the NAM report’s economic cost component and from the legislative interventions of the past two decades—it is appropriate to cautiously recognize the higher economic costs that we have pointedly left flat since OMB referenced some $487 billion in 2001 dollars (Table 2) in keeping with the imperative to have official federal reports occupy center stage and their own inadequacy spur upgrades and reform. In yet another bow to conservatism, rather than $487 billion, this report has used a far more cautious $399 billion baseline in 2013 dollars. Updating that government-rooted but downsized figure to 2023 dollars yields a $522 billion marker we shall use. That’s still far below the NAM’s analysis but serves our purpose of setting some baseline.

Incorporating higher economic costs brings the total to $2.117 trillion, as reflected in Figure 1. We do not here credit four significant figures, but present them in the same spirit as OMB in its paperwork assessments that presented dollar values to the hundreds place, and time-spent precision to the quarter hour. This figure serves as a baseline to compare with metrics such as federal spending, and also a platform to which the FY 2023 and subsequent cost and paperwork revelations may be incorporated as a basis for coaxing and reiterating the administrative state’s duty to assess aggregates.

Inflating figures from a quarter century ago is a sketchy exercise, and it is fashionable for critics of cost–benefit analysis to claim that old rules like those in the legacy federal reports no longer impose costs because of technological change or adaptation. The distortions of regulation over time make that untrue, but nonetheless the NAM figures act as a container within which a conservative reckoning keeping government estimates intact can illuminate the inadequacy of official government reporting and spur improvement. For example, this report embeds a $418 billion annual estimate for environmental costs, also below the NAM $588 billion tabulation for that category, so we could have also updated that figure and may elect to do so in future editions of this report.

Indeed, much federal economic and social intrusion is not captured as costs of regulation or coercive intervention in any of the formats that purport to address or score them. Even mere numbers of rules were not tabulated before 1976. Like the NAM report, other assessments acknowledge regulatory costs far beyond the official reckonings, such as former White House Council of Economic Advisers chief economist Casey Mulligan’s report, “Burden Is Back: Comparing Regulatory Costs between Biden, Trump, and Obama.” These exercises to broaden understanding are appropriate since OMB reports do not entail third-party objectivity but, as OMB acknowledges in recent editions of the Report to Congress, “All estimates presented . . . are agency estimates of benefits and costs, or minor modifications of agency information performed by OMB.”

In that vein, this report’s Appendix C presents a work-in-process sampling of omissions that involve more than a century and a half of economic consolidations and administrative state escalations. As the Competitive Enterprise Institute’s founder Fred L. Smith Jr. framed this dilemma, “The genius of the Progressives in the late 19th century was to preempt or push large sectors of the emerging future (the environment, schools, electromagnetic spectrum, infrastructure, welfare, the medical world) into the political world.”

These outside-the-framework costs include those of antitrust regulation, the predominance of public–private partnerships in large-scale infrastructure projects such as electric vehicle charging networks, clean hydrogen hubs, regional technology hubs, and other top-down cartelization and steering by subsidy, the perpetuation of ill-founded common carriage, resource-use restrictions on western lands, and the “too big to fail” stance toward large financial institutions—just to name a few.

The administrative state routinely disregards political failure, underplays the importance of private property, and fails to appreciate its own role in aggravating inequality. Yet the welfare-industrial complex is booming, extending even to an Internet for All initiative.

Even transfer and budget rules like the 104 noted in Table 3 can displace what would have been private activity in, for example, retirement and health care funding, distorting those markets in perpetuity. Washington’s insatiable appetite for inducing dependency on federal government transfers is as fundamental as social regulation and the custodial administrative state can get, yet it is not counted among costs. And of course, costs of subregulatory materials, such as agency memoranda, guidance documents, bulletins, circulars, and manuals, do not appear in OMB’s annual assessments.

Abundant, therefore, are the routes for getting to $2 trillion and beyond in costs of regulatory intervention, displacement, and consolidation. Equally abundant is the official inclination to disregard the scale and scope of such encumbrances. Regulatory costs have only compounded since the government bothered to tabulate aggregate social, environmental, and economic costs two decades ago. Table 3 and Appendixes A and B depict tens of billions of dollars added in only the most recent three years by a handful of the 400 federal agencies and subunits.

Regulatory cost burdens compared with federal spending and the deficit

Comparing regulatory costs with federal taxation and spending helps provide perspective on the foregoing. According to the newly released Congressional Budget Office (CBO) Budget and Economic Outlook, covering FY 2023 and projections for FY 2024–FY 2034, the federal government posted $6.135 trillion in outlays on revenues of $4.439 trillion, thus a deficit of $1.695 trillion.

According to the CBO, outlays are expected to cross the $7 trillion mark by 2026 and top $10 trillion annually by 2034. Deficits exceeding $1.5 trillion annually persist as far as the eye can see, passing $2 trillion in 2031.

Figure 2 compares deficits and outlays for fiscal years 2022 and 2023, and projected amounts for FY 2024, along with regulation. Regulation now stands at about 34 percent of outlays and easily exceeds 2023’s $1.695 trillion deficit. Applying the NAM regulatory aggregate cost figure of $3.079 trillion means regulation would reach 50 percent of the level of outlays.

Although spending and debt are tracked, official measurements to capture likely increased regulatory costs generated by highly regulatory legislative enactments are not prioritized. Unremitting projected deficits can also increase pressure to regulate instead of spend.

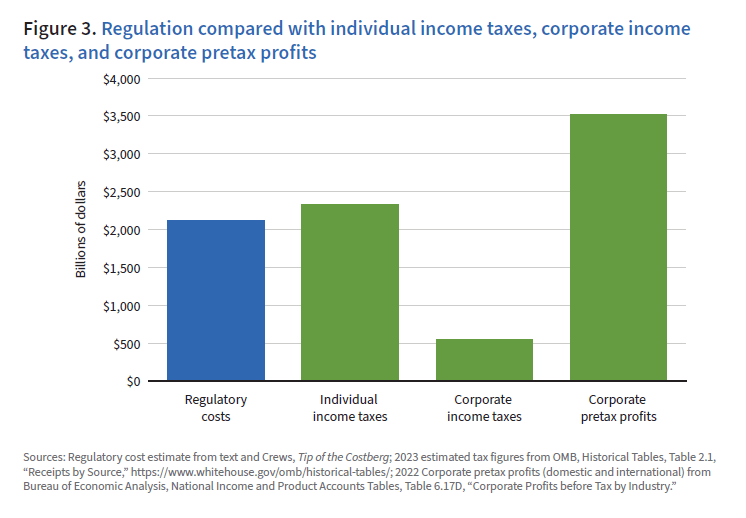

Regulatory costs compared with income taxes and corporate profits

Figure 3 provides a snapshot of our regulatory cost estimate of $2.117 trillion compared with taxes and corporate profits. Income tax collections from individuals stand at an estimated $2.33 trillion for FY 2023; corporate income taxes collected by the US government are estimated at $546 billion for FY 2023. Regulatory costs are nearly four times corporate income taxes and approach the level of individual income taxes. The NAM cost figure of $3.1 trillion annually would exceed the sum of both ($2.9 trillion). Meanwhile regulatory costs as depicted here are over 60 percent of corporate pretax profits of $3.5 trillion. The NAM cost figure of $3.1 trillion would consume nearly all corporate profits.

Regulatory costs compared with US gross domestic product

In January 2024, the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Economic Analysis estimated US current-dollar GDP for 2023 at $27.36 trillion. The regulatory cost figure of $2.117 trillion annually is equivalent to approximately 8 percent of GDP, or 11 percent if the NAM’s $3.067 trillion reckoning is used. Combining $2.1 trillion in regulatory costs with federal FY 2023 outlays of $6.135 trillion, the federal government’s share of the economy stood at $8.2 trillion in 2023, 30 percent of GDP (see Figure 4). None of these metrics include state and local spending and regulation.

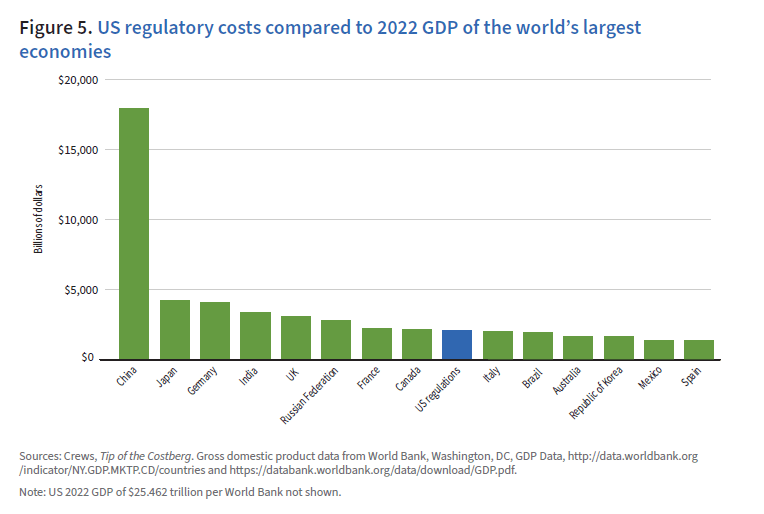

US regulation compared with some of the world’s largest and freest economies

If US regulatory costs of $2.1 trillion were a country, it would be the world’s ninth-largest economy, ranking just behind Canada, with its 2022 GDP of $2.14 trillion, and ahead of Italy at $2.01 trillion (see Figure 5). Using the NAM cost estimate, federal regulation would be the fifth-largest country, just ahead of the United Kingdom’s $3.071 GDP.

The US regulatory figure of $2.1 trillion not only exceeds the output of many of the world’s major economies, but also greatly outstrips even those ranked as the freest economically by two prominent annual surveys of global economic liberty. Figure 6 depicts the 2022 GDPs of the five nations ranked in the top 10 common to both the Heritage Foundation Index of Economic Freedom and the Fraser Institute/Cato Institute Economic Freedom of the World report. The Fraser/Cato index ranks the United States 5th, whereas the Heritage report ranks the United States 25th.

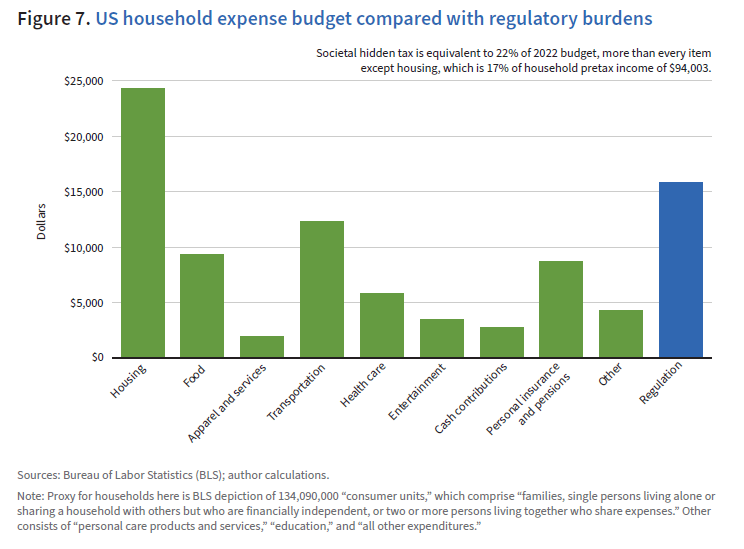

Regulation: A hidden tax on the household budget

Regulations are sometimes called a “hidden” tax for good reason. Ordinary income taxes are itemized on pay stubs and merit an annual household reckoning, whereas most regulatory costs are embedded in prices of goods and services. Regulations can affect households directly, or they can occur indirectly, such as when businesses pass on regulatory costs to consumers just as they do the corporate income tax. Other costs of regulation that percolate throughout the economy can find their way to households in their capacities as workers and investors in stock and mutual fund holdings of companies subject to regulation of all stripes.

The true incidence of regulatory costs is of course indeterminate. But by assuming a full pass-through of all regulatory costs to consumers, one can look at American households’ share of regulatory costs and compare it with total annual expenditures at the household level, as those are compiled by the Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics.

For America’s 134.1 million households, the average 2022 pretax income was $94,003 (compared with the prior year’s $87,432). If one were to allocate annual regulatory costs, assuming the full pass-through of costs to consumers, US households pay $15,788 annually in embedded costs ($2.117 trillion in regulation divided by 134,090,000 consumer units), or 17 percent of an average income before taxes (and of course more as a share of after-tax income). The NAM’s $3.079 trillion regulatory assessment would imply costs of $22,962 per household, or 24 percent of income.

Using the $2.1 trillion baseline, the buried regulatory tax exceeds every annual household expenditure item except housing (see Figure 7). Regulatory costs amount to up to 22 percent of the typical household’s expenditure budget of $72,967. That means the average US household spends more on hidden regulation than on health care, food, transportation, entertainment, apparel, services, or savings. The NAM’s $3.079 trillion regulatory cost of $22,962 amounts to fully 31 percent of household expenditures, still not exceeding housing costs but coming uncomfortably close.

Costs are one means of assessing the size and scope of the federal regulatory enterprise. Another is to assess the production of paper—the regulatory material that agencies publish each year in sources like the Federal Register.