A Global Antitrust Paradox?

The FTC is harming America’s race with China

Executive summary

In today’s Washington, bipartisan consensus is rare. But at least two points of consensus remain. The first is that America’s defining geopolitical challenge in the 21st century lies in its competition with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and that this competition is worth winning. The second is that US national advantage in that competition, to no small extent, is – and will continue to be – a function of technological innovation in cutting-edge technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI).

In the eyes of a bipartisan consensus, then, Lina Khan’s agenda at the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) should be regarded as a threat to vital US national interests. In a best-case scenario, it will slow down the pace of innovation in technologies, namely AI. In a worst-case scenario, it will result in a 21st Century that sees the CCP displace the US as the world’s preeminent geopolitical power.

The role of technologies like AI in shaping US geopolitical competition with the CCP may be unusual. If so the costs to the US national interest of Khan’s agenda may be unusual. But the bad economics of antitrust agendas like Khan’s is not unusual at all.

When the stringency of competition policy rises, all else equal, consumer prices typically rise and inflation-adjusted economic growth falls. If the typical relationships hold, if the US were to adopt the competition policies of Canada, US Gross Domestic Product (GDP) would be $134 billion lower and consumer prices would be between 0.5 and

0.98 percent higher. These results imply that increases in the stringency of a country’s competition policy come at the expense of national competitiveness and a country’s share of global GDP.

That represents, if not a paradox for antitrust policy, then at least a dilemma. The intentions of tighter antitrust measures may be domestic in nature. But even policies made with the best of intentions can lead to unintended costs. And this paper documents that antitrust agendas like Khan’s, whatever their intentions may be, come with unintended costs – costs that place the entire nation at an economic disadvantage compared to the rest of the world.

Lina Khan’s antitrust in an era of great power competition

A bipartisan consensus exists with regards to US competition with the CCP. That consensus rests on two pillars. The first is that America’s defining geopolitical challenge now lies in its competition with the CCP.

In their National Security Strategies, both President Biden and President Trump identified competition with the CCP as America’s preeminent geopolitical challenge. The second is that technological innovation will play a huge role in this competition. The last two US presidents said as much in the National Security Strategy that each released. In 2017, the National Security Strategy spoke of a focus on “preserv[ing] our lead in research and technology.”1 In 2022, the National Security Strategy spoke of “our innovation” as one of the “foundations of our strengths at home.”2 The verbiage has changed, but the substance has not. There is little doubt that US technological innovation is tied to US national interests.

The great importance of technological innovation to US national interests raises the stakes for the brave new direction that antitrust has taken under the Biden administration. Under Biden, a clear target of the antitrust spear is the US technology sector. A foundational document of the Biden administration’s antitrust agenda is Executive Order 14036. Signed by President Biden in July 2021, the Executive Order states that it is “the policy of my Administration to enforce the antitrust laws to meet the challenges posed by new industries and technologies.”3

FTC Chair Lina Khan has zeroed in on the specific technologies, like artificial intelligence, that are likely to be central to US competition with China. “We must regulate AI. Here’s how” is a headline that appeared above Lina Khan’s byline in the New York Times in May 2023.4 AI is likely to shape the future of US-China competition in commerce and even potentially on the battlefield itself. The People’s Liberation Army, the military wing of the CCP, has identified the integration of AI into its capabilities as a top priority.5

So has the US military.6 The US Department of Defense now even has Task Force Lima, its own for generative AI, the type embodied by ChatGPT.7

Among the examples of how Khan’s FTC has already undermined US national interests is its thwarting of NVIDIA’s proposed acquisition of chip-design firm Arm. Computer chips are at least as central to national security as they were during the 1970s and 1980s, when they were quite central.8 At the time NVIDIA contemplated acquiring Arm, Arm was owned by SoftBank, a Japanese firm, and NVIDIA is an American-based firm. NVIDIA’s acquisition of Arm, then, would have increased the degree control over the global supply chain for computer chips that resides in the United States. Yet Khan’s FTC sued to prevent NVIDIA’s acquisition of Arm from happening. It’s unlikely the FTC would have attempted to stop the acquisition were Khan not its Chair: its justification cited theories of harm from “vertical mergers” that the FTC typically did not cite until her arrival.9 Within months, NVIDIA ultimately dropped its pursuit of Arm, citing “regulatory challenges.”10 Around a year after that, President Biden himself was talking about the importance of having the supply chains that produce America’s computer chips reside within the United States.11 NVIDIA’s acquisition of Arm, thwarted by Khan’s FTC less than a year before, would have advanced the specific national security interests that Biden was talking about.

At present, Lina Khan’s tenure at the FTC appears on track to include a role in undermining US innovation in AI. Under her leadership, the FTC has shown no hesitancy in targeting the firms at the cutting-edge of AI. For instance, the creator of ChatGPT, OpenAI, is a crown jewel of the global AI universe that calls the United States home. It’s now under scrutiny by Khan’s FTC. In July 2023, it received notification that the FTC was investigating whether it “engaged in unfair or deceptive privacy or data security practices or engaged in unfair or deceptive practices relating to risks of harm to consumers.”12

At a minimum, OpenAI will now need to dedicate time and money to dealing with the inquiry. Beyond that, OpenAI’s innovators may also demur from technologically fruitful lines of inquiry for fear that it will run further afoul of Khan’s FTC, at least until the courts weigh in. Judges have ruled against the FTC when it brought cases motivated by Khan’s novel theories of how antitrust law might apply to new technologies. For instance, the FTC attempted to block Meta’s acquisition of a virtual reality company, Within, based on potential rather than actual harms. The case was brought by Khan’s FTC over the objections of the agency’s career staff.13

Misperceptions of law matter greatly for the economy when it’s the FTC Chair who has them. FTC cases and investigations that fail to lead to cases still impose costs on firms in terms of time, financial resources, and opportunity costs. The FTC’s inquiry into OpenAI may or may not prove to be fruitless as its inquiry into Meta’s acquisition of virtual reality content maker Within. Even if it is not, however, it will impose costs on OpenAI that undermine AI innovation in America.

Khan’s “big is bad, and Big Tech is especially bad” attitude has already led the FTC to harm many organizations that fuel AI innovation. That’s because of where the funding for AI innovation in the United States tends to come from. The biggest investors in AI are Big Tech firms. These firms fund investments in innovative new technologies with retained earnings that have been generated by their other lines of business. They do not fund it by issuing new equity or new bonds. Their investments in AI are no exception. These investments, and by extension US innovation in AI and competitiveness with China, are threatened by Khan’s ongoing litigation against Big Tech.

Meta is a case study in AI’s reliance on internal funding. In April of 2023, Meta, the parent company of Facebook, announced that it would invest $33 billion in artificial intelligence.14 In the universe of all US AI investment, that’s a nontrivial sum. By some accounts, in the first half of 2023, all venture capital investment in AI amounted to $15.3 billion.15

Meta is funding this investment from its retained earnings, which are, in effect, corporate profits from the past. For Meta, those stand at around $68 billion. Meta could not fund its AI investments with current profits, which were $23.1 billion in 2022.16 Nor is it issuing new equity, or shares of stock, that could fund these investments. In 2022, in fact, it bought back existing stock.17 Nor is it using bond markets to fund research and development projects like AI. It has issued corporate debt only once.18 Without these retained earnings, Meta’s investments in AI, which are much of America’s investments in AI, would not be possible.

It is worth emphasizing that other Big Tech firms fund their AI investments in ways that are as reliant on retained earnings as Meta is. Alphabet, parent company of Google, is another case-in-point. It does not seem to have turned to public stock and bond markets for new capital since 2020.19 Its ability to fund investments in cutting-edge technologies like AI relies on retained earnings and profits from existing lines of business. And the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division is now suing Google in a case that would threaten its core, profit-generating lines of business.20 If the Department of Justice succeeds, the source of the funds that allow Google to invest in AI will be, if not eliminated, at least harmed.

You could write a version of this script for Khan’s FTC harming US innovation, while swapping out Meta for other Big Tech firms, like Amazon or Apple. Each of these firms is investing in AI and other cutting-edge technologies like it. Each of these firms funds these types of investments with profits accumulated in the past and retained until the present. Each of these firms has faced a level of heightened scrutiny from the FTC under Khan, whose hostility towards Big Tech predates her time at the FTC. At each of these firms, then, Khan’s FTC seems poised to pursue an agenda that would have the effect of undermining the firm’s ability to accumulate and retain earnings to fund investments in AI.

If the FTC’s does ultimately undertake regulatory or enforcement action that causes Big Tech’s existing investments in AI to cease to be profitable, the costs would fall on a range of actors beyond Big Tech. That’s because such FTC action would have the effect of lowering the expected rate of return on future investments in AI. With a lower expected rate of return, there would be less investment the AI space, including for newer start-up firms. That decrease in funds available for AI startups would, in turn, harm downstream businesses that benefit from innovation in AI as well as consumers. The breadth of these implications for the returns on existing investments in AI, much of which has been made by Big Tech, clarifies another conceptual point. The case against FTC enforcement that jeopardizes investment in AI, then, is not a case for Big Tech for Big Tech’s sake. It is a case for investment in AI for America’s sake.

The nature of competition between the US and the CCP may upgrade FTC action that harms US innovation in AI from an issue of direct economic costs to one of geopolitical as well as direct economic costs. But this upgrade to worse comes from a baseline of bad. The agenda of Khan’s FTC would have real economic costs regardless of the state of geopolitics. As the next section documents, where antitrust agendas like Khan’s appear, for the country as a whole, bad economic consequences tend to follow.

The economics of antitrust in global perspective

Economists and other scholars have spent decades quantifying how some policies affect country-level economic outcomes. The ideal analysis permits causal inferences that separate the wheat of causation from the chaff of mere correlation. Antitrust policies have not been a great focus of such efforts. To some extent, that may reflect the tendency of debates in antitrust policy to revolve around legal debates, which can center around questions of intent, rather than around economic debates, which tend to focus on the unintended consequence of policies as much as their intended consequences. This section attempts to fill that gap by quantifying the effects of antitrust policy on economic outcomes like real GDP per capita and inflation.

Any quantification of the effects of economic policy on outcomes requires data over time on that set of economic policies within countries. The current gold standard for such data, which was introduced in 2018, is the Competition Law Index (CLI) by Columbia University’s Anu Bradford and the University of Chicago’s Adam Chilton. The CLI Index spans 1890 to 2010 and covers 134 countries.21 For each country and year in the sample, the CLI assigns a value between zero and one to the overall stringency of competition law.22 Beyond this headline rating, the CLI assigns numeric values to subcomponents of competition law, like merger control.

Google Scholar reveals that existing scholarship has used the CLI index to quantify the effects of competition policy only on equity-motivated outcomes, like income inequality and labor’s share of income.23 Attempts to quantify the effects of competition policy on efficiency-motivated outcomes appear to be absent. This paper attempts to fill that niche.

This paper’s baseline set of regressions merge economic data from the World Bank with data from the CLI. Because the World Bank data start in 1960, in the merged data, the timeframe runs from 1960 until 2010.24 These panel regressions also include two sets of controls. The first is a control for the income group that the World Bank classifies a country as belonging to in a given year.25 The second is a control for the calendar year.26 To deal with the influence of outliers like Zimbabwe on estimates of average inflation, annual rates of inflation were top-coded at fifty percent. An effect of that is to bias the estimated average effect of increases in the stringency of competition law downward, as outliers higher than 50 are encoded only as 50.

This statistical setup addresses a number of concerns that may be raised. The first is that country-level characteristics that affect inflation and real GDP growth, like corruption, may correlate with the level of stringency in a country’s competition policy. But these regressions are looking at the influence of year-over-year changes in the level of the stringency of competition policy. Country-level characteristics that tend not to vary much over individual years with a given country, like the independence of monetary policy, would not be expected to influence their results. And the inclusion of variables for World Bank income classification addresses, however imperfectly, the influence of policy characteristics, such as corruption, that may tend to vary little over years but much over the course of decades, perhaps like antitrust policy, as a country develops. There are certainly omitted variables that are liable to bias these estimated effects of competition policy to be too large. By construction, however, they are likely limited to things that change within countries specifically in years in which competition policy changes.

In policy debates, a number of other jurisdictions have served as references with regard to possible directions for US antitrust policy. One is the European Union (EU). The EU is often referenced in discussions of antitrust in the United States, including by policymakers.27 Another is Canada. Judged by a letter from Khan and the assistant attorney general in charge of antitrust at the Department of Justice to the Canadian Ministry of Innovation, Science, and Economic Development, US antitrust policymakers and their counterparts are in regular contact to exchange ideas.28 That exchange of ideas addresses areas of active policy upheaval, like merger oversight. A third is China, a frequent reference point for antitrust approaches to the technology sector.29

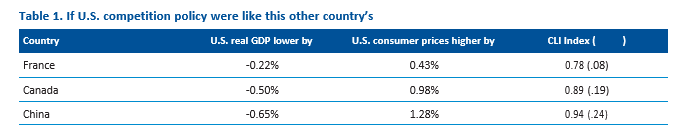

The table below shows the expected effect of the US moving to the level of stringency in competition policy in each of these three jurisdictions on real GDP and consumer prices.30 France serves as the country-level stand-in for the EU. Each row in the table shows the economic effects that the US economy could expect to experience if it mimics the competition policy of that other country. The estimated effects are significant and troubling. If the US adopted a competition policy as stringent as Canada’s within a single year, for example, in the following year you could expect the growth of US GDP per capita to be 0.5 percent lower and consumer prices to be 0.98 percent higher than they’d otherwise be. The final column shows each country’s overall CLI Index, as well as its difference over the US level of 0.70.

These estimates of average effects on real GDP and consumer prices are plausible upper-bounds on the effects of competition policy.31 That’s because they are based on increases in the stringency of antitrust policy that likely correlate, in their timing, with other country-level changes in economic policy that raise inflation. At least in the case of Khan’s arrival to the FTC, that concern about correlated policy changes seems to be borne out. A number of policies undertaken under the Biden administration, unrelated to the FTC itself but co-incident in timing to her arrival at the FTC, have plausibly raised consumer prices.

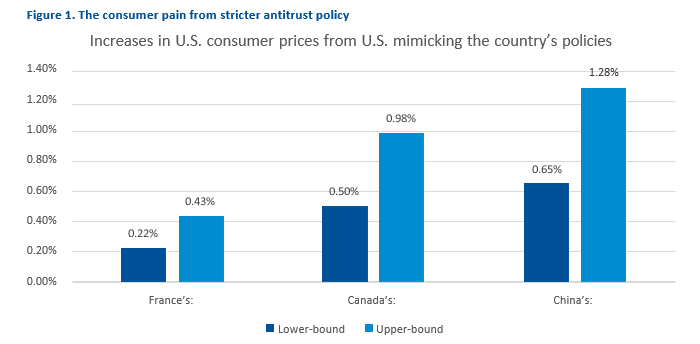

One method for calculating a lower-bound for the inflationary effect of increases in the stringency of antitrust enforcement comes from the Quantity Theory of Money.32 If the money supply determines the level of nominal GDP, holding money supply constant, any decrease in real GDP necessarily implies a corresponding increase in the price level. Antitrust policy does not generally affect the money supply. It is plausible to hold the money supply constant when calculating its expected effects of changing antitrust policy on inflation, when using this approach. If you use this approach, any decrease in real GDP is equal in percentage terms to the increase in the price level. Because of that, the decreases in real GDP documented in Table 1 double as the lower-bound estimates for increases in inflation that are shown above in Figure 1. Figure 1 shows these lower-bounds alongside Table 1’s estimated effects, which serve as the upper-bounds, for each of these three scenarios for US competition policy.

These are not annual effects that would be expected to show-up every year as the US converged towards Canadian levels of antitrust over time. They are the cumulative effects that you’d expect to arrive once that convergence finished. If the US were to ratchet- up toward Canada’s level of competition policy over four-years, for instance, that 0.98 percent increase in consumer prices would increase average consumer price inflation by 0.24 percent per year.33

The expected decrease in real GDP of 0.5 percent from the US adopting Canada’s competition policies implies that Q2 2023 US GDP would have been $134 billion lower if it had Canada’s competition policies. That may strike some observers as high enough to stretch the imagination. But a glimpse at the full set of economic effects that would arrive from FTC enforcement on Amazon, to take one company as an example, suggests that it is not implausibly high at all.

For starters, a likely effect of inaugurating a post- Amazon world would be to raise prices for consumers. Economists have documented an “Amazon Effect” on brick-and-mortar retail pricing.34 That effect is consistent with competition from Amazon holding down the ability of brick-and-mortar retailers to raise mark-ups on goods sold to consumers. A consequence of the loss of that “Amazon Effect” would be higher prices at brick-and-mortar stores around the country. That would lower real GDP both by definition (prices for the same goods are now higher) and by depriving customers of money they would then not be able to spend elsewhere in the economy. As prices rise for once-on-Amazon goods, like energy drinks, then customers would have less cash to spend on their never-on-Amazon services, like haircuts.

Beyond that, through the stock market, consumers would face a massive wealth shock from any transition to a post-Amazon economy. Amazon’s market capitalization is now around $1.7 trillion. According to one recent estimate, households spend wealth at a rate of 14.6 percent annually.35 That means that $1 in lost wealth means 14.6 cents in lost spending by the end of the year. By one estimate, US investors own around 90 percent of Amazon’s stock.36 Taken together, these numbers imply that FTC enforcement on Amazon that caused its share price to fall by 50 percent would result in a drag to consumer spending of $111.7 billion, and that enforcement that caused its share price to drop by 25 percent would result in a drag to consumer spending of $55.9 billion. These numbers do not seem at odds with a $134 billion overall cost number from the US adopting antitrust as stringent as Canada’s.

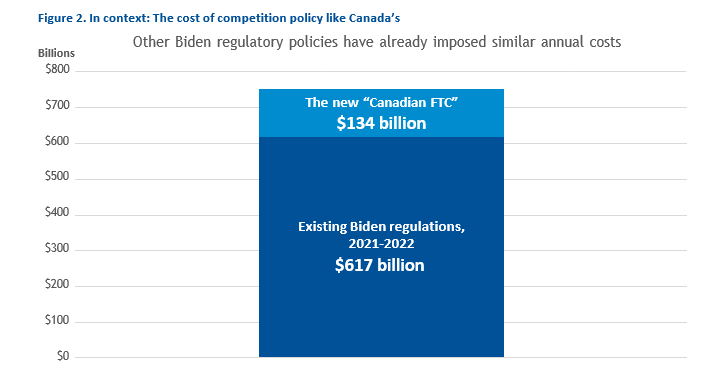

Nor would an $134 billion cost increase be out of step with the magnitude of the costs imposed by the other regulatory actions of the Biden administration. The cost-benefit estimates prepared by the federal agencies themselves, according to University of Chicago professor Casey Mulligan, indicate that the regulatory actions undertaken by the Biden administration through the end of 2022 impose annual costs of $173 billion.37 Mulligan’s own analysis addresses a richer range of economic effects than the cost-benefit analysis of the federal agencies. That analysis suggests the regulatory activity undertaken by the Biden administration through the end of 2022 impose overall economic costs of $617 billion per annum. An additional $134 billion in costs arising from the FTC matching Canada in terms of stringency of competition policy does not look like a stretch.

Because the $134 billion in costs is comparable more to Mulligan’s overall $617 billion in new costs than the agencies’ $173 billion in costs, Figure 2 puts these estimated costs in the context of Mulligan’s $617 billion figure.

In addition, the CLI allows for additional scrutiny of an antitrust policy area of particular focus for Khan’s FTC: mergers. The FTC’s new Merger Guidelines, released in July 2023, aim even at mergers between vertical suppliers that do not compete in the “horizontal” manner that has been the traditional focus of antitrust.38 The CLI has a sub-index specifically for the scrutiny of mergers.

If we consider changes in competition policy for mergers, the direction and nature of the results do not change. The estimated effects for both real GDP and inflation remain in the expected direction. That said, the sizes of the estimated effects do decrease. The size of the estimated effect of the merger sub-index on inflation is 63 percent of what it is for the overall index of competition policy, and the size of its estimated effect on real GDP growth is 72 percent of what it is for the overall index. But these are still non-trivial and negative expected effects.

These results sound a cautionary note for policymakers in the United States who are inclined to view European Union, with policies like the Digital Services Act, as something of a model of antitrust policy in the United States. Those policymakers, if the FTC’s coordination with its counterparts in the EU is any indication, may include Lina Khan herself.39 Much of the European Union has spent the last few decades lagging the US in economic growth, with the advantage that the US enjoys over much of the EU in terms of inflation-adjusted GDP per capita growing over time.40 This paper’s results suggest that the EU’s lackluster growth is no coincidence, given its antitrust policies. These results, after all, document that antitrust policies like the EU’s tend to come with lower rates of inflation-adjusted economic growth. Unless policymakers want to replicate the EU’s anemic rates of growth in the United States, then, they should not seek to emulate the EU’s antitrust policies.

Beyond the United States, they’re also a cautionary tale for policymakers in other countries, like the United Kingdom. The UK appears to be contemplating changes in antitrust policy that would increase its stringency.41 The UK is also experiencing a “cost of living crisis” characterized by high inflation and low inflation-adjusted growth. According to these results, policymakers in the UK would be ill-advised to move forward on tightening antitrust policy, unless they want to see the “cost of living crisis” worsen. Policymakers, in the UK as in elsewhere, tend not to think of antitrust as an issue that has macroeconomic consequence. They should think again.

A global antitrust paradox?

These results complicate cases for antitrust enforcement that are rooted in claims that antitrust increases measures of relative gain within countries. Labor’s share of output, a measure of wages as a share of GDP, is one example. It is a measure of relative gain that some have cited to argue in favor of stringent antitrust. “If it is the case that competition policy and the labor share are related in a positive way,” in the words of one observer, “then this suggests that effective competition policy could generate positive effects beyond its traditional efficiency goals and result in labor receiving a higher share of welfare gains.”42 This paper’s results show that is not the right way to think about competition policy.

Wages as a share of GDP can rise not because wages are rising, but because GDP is falling while wages are either stagnating or falling at a slower rate than GDP. In such a world, labor’s share of output has risen, but workers have not received a “higher share of welfare gains” from antitrust enforcement. Instead, they’ve borne a lesser share of the welfare losses that antitrust policy has imposed. This paper’s results on inflation and GDP suggest that we are living in such a world. Stricter antitrust really does tend to lower real GDP.

In such a world, antitrust policy would have effects that look, at least to some, like a paradox. It would improve some measures of equality, like labor’s share of output, that define success as the gains of one group relative to another. But that purported “success” at turning one set of Americans into relative winners would be thanks to having shrunken the GDP available for all Americans. You give some a growing slice of the American pie, in effect, by shrinking the pie.

Can that be considered a policy success? It seems hard to say that the answer is yes. If success is defined relative to others, some Americans have succeeded. Viewed at a global level, however, America as a whole is worse-off relative to other countries.

Conclusion

Khan’s agenda at the FTC is a bad idea that could scarcely come at a worse time. To say that the fate of the free world depends on US competition with the CCP is only to paraphrase what is now a bipartisan consensus. The outcome of that competition may depend on the pace of US technological innovation in fields including AI, which Khan is working hard to thwart.

More broadly, a country’s competition policy has serious and previously underexplored ramifications for economic growth, inflation, and global competitiveness. And the effect size is non-trivial, even by macroeconomic standards. America’s real GDP would shrink by half of a percentage point, or around $134 billion, if the FTC adopted competition policies like Canada’s.

Because stricter antitrust harms real economic growth and raises inflation, even if it benefits some within a country, it ultimately causes the country as a whole to fall behind the rest of the world. In the race of the US versus China, that could have negative geopolitical implications as well.

About the author

Joseph W. Sullivan is a senior adviser at The Lindsey Group, a macroeconomic advisory and forecasting firm. He is also a Visiting Scholar at Florida International University’s Institute of Environment. From 2017 to 2019, he served as a staff economist and the special adviser to the chairman at the White House Council of Economic Advisers.