Constitutional Restoration: How to rebuild the separation of powers

Introduction

A specter is haunting America—the specter of unlimited government.

A central feature of our Constitution is that it restricts the federal government’s powers. These restrictions are, in part, structural. Not only does the Constitution designate the limits of federal power beyond which the government cannot go, but the structure of the Constitution also separatesand balancesvarious executive, legislative, and judicial powers. These restrictions not only limit what the government can do, but they also limit which part of the government may do it. This demarcating, separating, and balancing is supposed to prevent any one branch of government from wholly dominating another.

There is tension between this classical vision of American constitutionalism and the day-to-day proceedings of the modern administrative state. In particular, many federal agencies—some that are independent and others that are part of the executive branch—now wield a multitude of both executive and non-executive powers. That is: some of these powers appear to be executive in nature, but others appear to be legislative or judicial. For instance, several Cabinet agencies now exercise powers once confined to just one of the three branches of the constitutional triad. Such agencies now investigate and prosecute those who are alleged to have broken the law (an executive function); they issue rules with the force of law (a legislative function); and they conduct hearings, trials, and appeals to apply the law (a judicial function). Those who observe these agencies exercising various powers—especially when those powers cross intragovernmental property lines—may wonder what is left of the Constitution’s promise of the balance and the separation of powers.

Both the separation and the balance of powers are vital elements of American governance. In this paper, we recommend setting new boundaries to restore these structural aspects of governance to their proper place. We provide a detailed plan to divest non-executive powers from federal agencies. Broadly, legislative powers should be reassigned to Congress, and judicial powers should be reassigned to Article III federal courts. This restructuring would revive classical American constitutionalism. It would also be a sea change in American governance. If a label is needed for this reconstruction and repair, it might be called Constitutional Restoration. Constitutional restoration will banish the specter of unlimited government, relegating it to the dustbin of history.

The importance of restoration

Constitutional restoration, as applied to the modern administrative state, is essential to good government—and not just because it makes for a cleaner or more aesthetically elegant federal structure. In Federalist #47, when James Madison wrote that “the accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands” may justly be called “the very definition of tyranny,” he was not just explaining the formal beauty or the aesthetic importance of a well-designed organizational chart. Madison’s fundamental concern was that a collapse of the separation of powers would create terrible consequences for real people’s lives, because it would demolish the system of limited government that is a necessary condition of individual freedom.

The failure to preserve the separation of powers has led to much injustice today. Many federal agencies have in-house court systems. These are administrative law courts for which the agencies hire and fire their own judges, set their salaries, and write binding rules of procedure. These agencies employ both prosecutors and judges; it is no coincidence that the agency’s position almost always prevails in its own court. It is reasonable to suspect that a judge who regularly decides cases in which his or her own at-will employer is a party might find it difficult to mete out impartial justice. Consider the Federal Trade Commission: It has won every case in the last 25 years that it has brought before its own administrative judges.[1]

Some agencies administer their own appellate courts. In the event that the agency’s position does not prevail at trial, the agency routinely appeals to its own appellate division. In other agencies, the agency head serves as the appellate body. In such cases, the agency head is authorized to overrule the agency’s trial courts. The private litigant at odds with any such federal agency is, therefore, in a far worse position than the typical opponent of the government in court. After all, most people who are told that “you can’t fight City Hall” nonetheless receive, at the very least, the protections offered by an independent judiciary. The idea that the head of an agency might exert control over both a prosecutor and a judge in the same case will strike many as not just a breach of due process, but a breach of natural justice.

Furthermore, an independent or executive agency with rulemaking powers can enable a different kind of system failure—which is to say, a different kind of injustice. Such agencies issue rules with binding force. That rulemaking power is, fundamentally, a legislative power. People vote for U.S. senators and representatives: these elections authorize and legitimize congressional legislation. Without the public accountability that is created by elections, the moral authority of government actors to make law appears relatively weak. When legislative authority is delegated to government officials without direct accountability to the voters, this short-circuits the public’s ability to exercise self-government through the ballot box. In other words: bureaucracy replaces democracy.

Furthermore, the abundance and variety of directives from federal agencies creates a related problem: both the volume and the nature of such directives make it increasingly difficult to understand what the law is.[2] This is not solely a point about the relationship between how many laws there are and the difficulty involved in understanding them. The problem is, at least as much, that federal offices and agencies now regularly issue a dizzying number of “guidance documents, memoranda, bulletins, circulars, and letters that carry practical (if not always technically legally) binding regulatory effect.”[3] These are commands that bind the public in a manner that Congress has typically never seen or considered; furthermore, a substantial portion of these binding commands are not subject to any kind of formal rulemaking and public comment procedure at all. This is a failure both of accountability and of the rule of law.

Some make the counterargument that the public’s ability to reward or punish the president at the ballot box solves this problem of accountability: this is the theory that the president faces electoral accountability for the choices made by executive appointees. This counterargument is weak: the electorate should not be punishing or rewarding the chief executive for decisions that are fundamentally legislative in nature. The modern administrative state’s failure to achieve the separation of powers—replaced by its combination of executive and legislative powers into one entity—is at the center of this problem: fundamentally, the problem of mixed and mingled political accountability will not be solved by holding the president responsible for the policy decisions of executive or independent agencies.

Congress is a deliberative body that makes decisions through a fundamentally different process than a single-headed executive. At its best, the legislative process incorporates minority views to improve the policy implementations proposed by the majority. It is a fact of life that presidential and congressional decisions will sometimes be in conflict. Our constitutional structure of separation of powers and balance of powers is supposed to mediate that conflict by forcing accountability to be legible—and, ideally, completely transparent. Modern institutions that evade such mediation by lumping executive and legislative powers together have failed to comport with the political protections that the Constitution is supposed to provide. The Framers certainly did not believe that democratic accountability was a sufficient condition for good government; they believed that the divided government of the Constitution offered what they called “auxiliary precautions.”[4] An agency that both makes law and then executes it may not quite qualify for Madison’s “definition of tyranny,” but it certainly is slouching towards it.[5]

As Professor Todd Zywicki once told us:

I remember the first day I went to work at the Federal Trade Commission. I had previously had relatively little exposure to the agency: I certainly knew the law of antitrust and consumer protection, but I didn’t know as much about agency practices. So I sat down with one of the staff lawyers in the office, who explained to me how FTC adjudication worked: first the FTC launches an investigation, then the commission votes on charges. Then the agency pretends like it has never heard of the case before, it goes to an FTC administrative law judge, and the theory is that the agency sets up an internal, impenetrable wall between the enforcement division, the general counsel’s office, and the commissioners. Then the judge issues the verdict; then, if necessary, there’s an appeal to the FTC commissioners after the trial stage. I heard all this and I said “No. No way. You’ve got to be kidding me. That can’t be true.” Of course, it’s all true. And the point of my story is that there’s a deep and indeed fundamental tension between the real world of the FTC and the way that just about everyone in the world thinks that the federal government, constitutionally, is supposed to function.[6]

Congress has made some attempts to move closer to the classical vision of the separation of powers: some of those attempts are less than ideal.[7] Most notably, the U.S. House of Representatives passed H.R. 2811 earlier this year: the central purpose of the bill was to raise the debt ceiling, but it also contained a secondary provision that would give Congress significantly more control over policy measures established by the rulemaking process. More specifically, if H.R. 2811 were to become law, then Congress would have to enact a joint resolution of approval for each major rule to make it go into effect; without such a resolution, the rule at issue would not become binding.[8] Although Congress’s attention to rebalancing constitutional powers is a welcome phenomenon, this secondary provision is less than ideal in at least one respect: it preserves the core of policymaking power in the executive branch. In this paper, we describe a way to accomplish what we take to be the goals of H.R. 2811’s secondary provision: one way in which our proposal is different is that it situates policy decisions in Congress, the branch of the federal government that is best suited to make such decisions. Our proposal thus describes a viable avenue to reform: it assigns Congress regulatory and policymaking power; it avoids the criticism made of many regulatory reforms (namely, that such regulatory reforms are an ill-disguised attempt to stifle regulation generally); and, for the most part, it can be passed into law with the votes of a simple majority of the House and the Senate.

Implementing constitutional restoration

Any significant change to a complex system will present challenges. Constitutional restoration in the administrative state is no exception. Just below, we provide a clear and concise set of recommendations to achieve the goal of constitutional restoration. There is nothing mysterious about the idea that the executive should be in charge of executing, the legislature should be in charge of legislating, and the judiciary should be in charge of judging. The nature of constitutional restoration is easy to explain and understand, even though politically it will likely be challenging to accomplish. (As a former governor of California famously said: “There are simple answers, there just are no easy answers.”[9])

A proposed scope and pace of reform. We do not recommend immediate, across-the-board implementation of constitutional restoration. Instead, the implementation should begin by choosing one or two agencies—say, the Department of Commerce and/or the Federal Communications Commission—and then putting constitutional restoration into action on a small-scale basis. Incremental reform—that is, reform that can be implemented over time, not in a single episode—will allow for the capable and efficient administration of both our proposed reform and of government generally.

A proposal for judicial reform. In theory, the judicial reform portion of a constitutional restoration agenda is simple. Congress should end all relevant funding for all binding adjudicators and quasi-judicial bodies housed in executive and independent agencies. Simultaneously, Congress could expand funding for additional Article III trial courts that can hear the cases and controversies that agency courts would formerly have heard. One difficulty with this proposal is that, when enacted, it might create disproportionate influence for the president who chooses judges at that time; another difficulty is the time and labor involved in the selection of new federal judges.

Therefore, an arguably superior option would be for Congress to fund a new system of federal magistrates with more or less the same function as current administrative courts: these new tribunals could issue judgments that would be directly appealable to Article III appellate courts. These federal magistrates would be appointed by and accountable to the circuit courts that would hear appeals of the magistrates’ judgments. These federal magistrates could be experts (or be charged with becoming experts) in specific areas of law; they would be accountable only to and removable only by independent judges. The composition of this new collection of magistrates would be driven by the choices of judges; the current balance of the circuit courts would likely give neither political party an appointment advantage.

The jurisdiction of these new judicial bodies could be limited to matters of administrative law, which would allow the members of the new bench to be selected only from attorneys and judges with specialized technical training and experience. The requirements that this proposal implies for subject-matter jurisdiction and technical expertise are certainly not unique to it, as can be seen by the existence of the Court of Federal Claims and the Court of International Trade.

Not only would this proposal restore judicial power to where the Constitution vests it, but it is also likely to speed up final decisions. It has been noted since the days of Magna Carta that justice delayed is justice denied. Indeed, many of the worst excesses of current administrative enforcement procedure are represented by long, drawn-out judicial proceedings where it can be said that the process is the punishment. In effect, administrative enforcement procedure regularly allows an interested party (that is, the agency) to have practical control of the litigation calendar and to abuse that control for strategic reasons—to, for example, slow-walk a case when it’s to a prosecutor’s advantage. This is just one of many reasons that litigants before an independent judiciary can have greater confidence that they will be treated fairly.

Would the implementation of this judicial reform plan be cost-free? Almost certainly not. But a large portion of the costs in creating new courts would likely be covered by resultant savings from elimination of the quasi-judicial duties currently carried out by administrative agency personnel. The use of federal magistrates would also relieve the burdens of selection and confirmation faced by the executive and Congress, which must choose all judicial personnel in Article III courts.

A proposal for legislative reform. Similarly, the implementation of legislative reform that would create constitutional restoration is, in theory, not hard to understand: Congress should do its job. More precisely, Congress should be encouraged to do its job—legislating—through institutional incentives that will encourage it to carry out its duties. Congress regularly produces relatively broad and vague statutes. These statutes regularly include authorizations for executive agencies to write new rules to plug the legislative gaps that Congress has left open. Our proposed reform consists of a detailed plan that disciplines Congress to do the work it currently leaves undone.

The very first sentence of the first Article of the Constitution explains that all federal legislative powers shall be vested in Congress—which is to say: Congress, and only Congress, may legislate. Our view is that when Congress passes legislation that contains instructions like “the Commission may prescribe rules which define with specificity acts or practices which are unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce,”[10] it has dropped the ball. Or to put it a bit more charitably: in such circumstances, Congress has behaved like a runner at a track meet who passes the baton to someone else. If it is true that Congress, and only Congress, may legislate, then delegating legislative duties to federal agencies should be discouraged—and, ideally, eliminated. We provide a plan to accomplish this goal—which, as a practical matter, would essentially replace agency rulemaking with what we call supplementary legislation, which we describe below.[11] Just as we propose replacing administrative courts with judicial courts, we propose replacing executive rulemaking functions with legislative functions. Just below, we provide a specific plan to restore Congress’s proper constitutional role and function.

First, Congress should end certain funding by using appropriation riders—that is, the funding that currently supports the rulemaking staff operations that are found in most agencies. This excision would leave enforcement and administrative operations untouched. Zeroing out this funding, and the operations it supports, would, for the most part, strip the agencies of resources they currently need to issue rules; such rulemaking would therefore end. Similarly, the issuance of guidance documents would, for the most part, end. However, as part of their enforcement and administrative functions, agencies would remain free to issue guidance documents to explain the limits of and defenses to their enforcement powers.

Second, Congress should provide funding for two new congressional committees, consisting mainly of specialized, professional staff. The main output of these new committees would be supplementary legislation—that is, the committee’s output would largely be confined to gaps in the law that Congress, in previously passed legislation, had left unspecified. When passed into law, these instances of supplementary legislation would have more or less the same functions and consequences as agency rulemaking does now. (As a formal matter, a central norm of agency rulemaking is that it must stay within the subject-matter boundaries of what one might call the “primary” legislation that enables it. The supplementary legislation that is implied by constitutional restoration would have to stay within the same boundary line.) These two committees (one in the House, the other in the Senate) might each be named the Committee on Supplementary Legislation.

These committees’ jurisdiction would be confined to producing supplementary legislation that explains, with a high degree of specificity, matters of binding law that already-passed legislation had left unresolved. The legislative rules governing the production of supplementary legislation would require each piece of such legislation to include a clause explaining that, in case of any conflict between the supplementary legislation and the primary legislation that enabled it, the primary legislation would govern.

These two committees would have special jurisdictions and powers specified by the House and Senate rules that create them. Each of these two committees would have the power to issue supplementary legislation; as described at some length below, the production of such legislation would be subject to unique legislative procedures. Any such supplementary legislation would necessarily be limited to elaboration and explanation of gaps in the law that had been described in already-passed primary legislation. In other words, the function of supplementary legislation issued by this committee is, by and large, to replace the rulemaking process and the regulation that it creates.

From the perspective of legislative representation, each of these two committees on supplementary legislation could be structured in much the same way that the House Rules Committee and the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration are now. Each committee would be structured so as to contain reasonable legislative representation from both the majority and minority party. The staff requirements and workload implied by the creation of these two committees would be relatively large, however, mainly because our proposal requires technically knowledgeable professional staff to draft the supplementary legislation.

Alternate staff configurations could also be considered. The architects of constitutional restoration might choose instead to create a relatively small cohort of committee staff who would work cooperatively with already-existing professional staff on other committees; those committees might either repurpose existing staff to perform this new legislative work or beef up staffing on currently existing committees to shoulder the new workload. Other permutations of staffing that would satisfy these new congressional needs might even include funding additional positions for non-partisan staff with specialized or technical knowledge at the Congressional Research Service. The specifics of organization charts do not matter very much, so long as the overall goal is met: namely, ensuring that the specialized knowledge held by agency regulators will be preserved in the course of staff transfer to Congress.

Notably, this legislative structure would, by and large, make the ordinary notice-and-comment procedure that is required by the Administrative Procedure Act unnecessary.

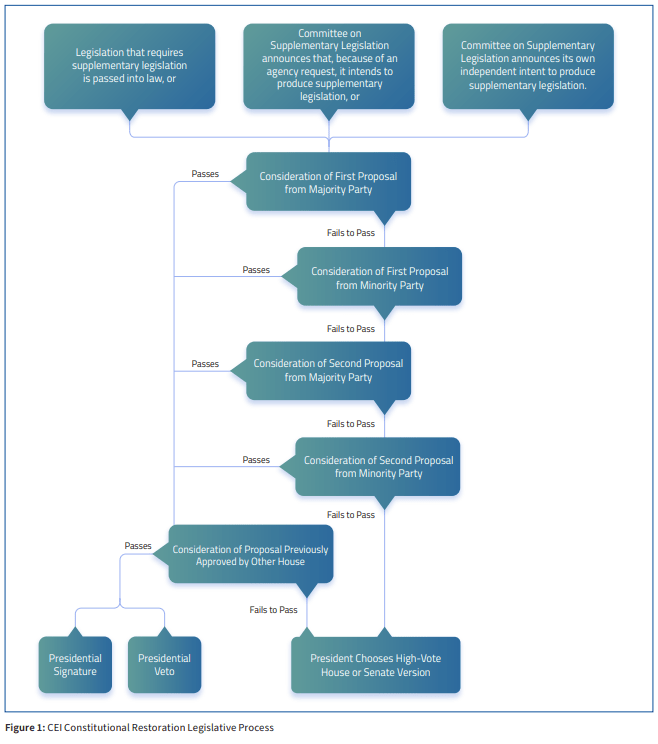

The establishment of special floor procedures would be necessary to make this proposal operate successfully. A central goal of constitutional restoration is to encourage Congress to act, rather than to behave passively and therefore fail to produce supplementary legislation. In our view, the best way to organize the appropriate legislative procedure is to deem one day of each month’s legislative calendar Supplementary Legislation Day. Ideally, both the House and the Senate would establish a Supplementary Legislation Day on their legislative calendars, such that a Supplementary Legislation Day would occur roughly every two weeks. On that day, the bills created by the Supplementary Legislative Committees would be sent to the floor. The bills emerging from this committee, unlike the product of most legislative committees, would be non-amendable, non-debatable, and (in the Senate) not subject to filibuster.[12]

An essential feature of our proposal is the contingent right of the minority leader in each House to bring up his or her own version of supplementary legislation—but only if either the majority party’s version fails to receive a majority of the vote, or if nothing pertinent is brought to the floor by congressional leadership within some fixed period of time. If either party’s version is brought up on the floor but fails to receive a majority of the vote, this failure would create an opportunity for the other party to bring up their own version of the supplementary legislation at issue after some given period of time.

For instance, the rule might be: after the majority party’s version is brought up and fails to receive a majority vote, then the minority party’s version is brought up on the next month’s Supplementary Legislation Day. Further: if the minority party’s version of supplementary legislation then either is not introduced after a given period or fails to receive a majority vote on the floor, then the majority party’s alternate (second) proposed version of the supplementary legislation may then be brought up on the next month’s Supplementary Legislation Day. If history repeats itself—that is, if the majority party’s second version of the legislation fails, as did the first, to get a majority vote or the majority party fails to present anything at all in the way of supplementary legislation, then the minority (like the majority before it) would get a second bite at the apple. This iteration would end if these four legislative opportunities for passage failed on the floor—although the four-step iteration might begin again if the majority party then decided to bring up another version of supplementary legislation on the same issue in the future.

For purposes of floor consideration, the legislative clock for any supplementary legislation would start to run for any proposed piece of supplementary legislation upon the occurrence of any of the following events:

(1) When legislation expressly requiring further detail is enacted;

(2) When the Committee on Supplementary Legislation announces that, because it has received a request from an independent or executive agency requesting a clarification of an existing law, it will begin work on producing supplementary legislation; or

(3) When the Committee on Supplementary Legislation announces that it has independently decided that an existing law needs clarification, it will begin work on producing supplementary legislation.

Some periods of time in the legislative rules that govern this procedure should be specified for reasons of notice. For instance, the period of time between the public notices described above and floor consideration might be a minimum of three months; the period of time between disclosure of the text of the supplementary legislation and the scheduled vote on that legislation might be a minimum of one week; the period of time at which the majority party’s first opportunity to present its legislation expires might be six months.

If one house were to pass supplementary legislation, the other house could then vote on that legislation at the next Supplementary Legislation Day. If that vote did not occur on that day, any member of the second house could then bring it up on a privileged motion thereafter. (In the event that some given number of Supplementary Legislation Days occur without the other house taking up the matter, the legislation would die.) When the two houses both pass supplementary legislation that is identical, it could then—like any other piece of legislation—be sent to the president for signature or veto.

As must be obvious, this proposed procedure is designed to encourage congressional action, not passivity. But we also propose one final failsafe measure: the exercise of some degree of presidential discretion. In the event that the Senate and the House failed to jointly pass a final version of some supplementary legislation, or if the president vetoed that final version, the president might then choose to send his or her own preferred version of the rule to the appropriate agency for public approval—which is to say, the agency must begin to subject the rule to the notice and comment process. But the president’s choice would be significantly constrained, because that choice would be restricted to one of the two previously proposed supplementary legislative proposals with the most support—that is, the president could only opt for a measure that is substantively identical either to the proposal that received the most votes on the House floor or the proposal that received the most votes on the Senate floor. (If two or more proposals each received the highest number of votes in either House of Congress, the scope of the president’s allowable choice would extend to any proposal that received the highest number of votes in either House.)

This presidential choice provision could be implemented for most agencies by means of an appropriation rider: the rider would prohibit the use of taxpayer funds to issue any regulation unless the content of that regulation had previously been selected by the president after undergoing the legislative process described above and receiving at least as many votes as any other alternative. Substantive authority to issue such regulations already exists; the rider would confine such issuances to the special circumstances described immediately above.

This final component of our proposed procedure should be sufficient to encourage the production of congressional legislation that will, for the most part, supplant and replace the system of administrative regulation we have today. (However, the reader who judges that our proposal is insufficiently attentive to legislative perspectives that are not embodied in the decisions of congressional leadership may find our alternative proposal, explained in Appendix B below, to be of interest.) To repeat: congressional action, not congressional passivity, is what is needed. That concern is the fundamental driver of our proposal. It’s easy for Congress to do nothing: it’s easy for Congress to avoid hard decisions (indeed, the delegation of policy choices by Congress to agencies bears a certain resemblance to the avoidance of hard decisions). The reason that our recommended procedure includes so many options for congressional decision-making is that we hope it might encourage our federal legislature to settle on one of them. The status quo, which now provides Congress with cover so that it can avoid making legislative and policy decisions, is a moral and constitutional failure.

Most of the functioning parts of our proposal for legislative reform could likely be written into House and Senate rules. This is not true with respect to the portion of our proposal that allows the president to choose his or her favored version of the rule: that is, a measure that requires the president to choose among various proposals to send one through the notice and comment process might require either or both an appropriations rider or substantive legislation. If this particular portion of our proposal never passed into law, or if this portion passed into law but the president failed to choose one particular instance of supplementary legislation with which to move forward, then it would ultimately be up to the courts to figure out how to fill gaps and ambiguities in statutes. It is our view that political pressure from the regulated community—a community that is highly attuned to the dangers of legal ambiguity and that requires a high degree of certainty in law in order to accomplish its goals—makes punting such questions to the courts significantly less likely.

Notably, our proposal for constitutional restoration creates a bevy of incentives for representatives of each party to put supplementary legislative proposals forward—either to produce a bill that will receive a majority on the floor or, failing that, to produce a bill that will receive more votes than any of its competitors. Our recommendations for constitutional reconstruction on the legislative side are meant to encourage Congress to decide and act (and, in some respects, to encourage the executive to decide and act), rather than to stay passive and produce nothing. These incentives should lead to rapid decisions when compared to the status quo. According to a GAO case study, the average time it took to issue a rule after first consideration was four years; the shortest time of issuance on record was one year.[13]

In other words, constitutional restoration has the virtue of speedy deliberation and resolution; it is realistic to assume that many instances of supplementary legislation could be issued by Congress and signed by the president within a year or so of the passage of some piece of enabling legislation that requires supplementary clarification. But speed is not the most important value that this proposal would advance; a much more important value lies in encouraging the responsible use of the constitutional powers of our federal legislature. Ultimately, the goal is to place the power of policymaking back into Congress’s hands—and, perhaps more importantly, to restore a significant measure of legislative responsibility and accountability.[14]

CONCLUSION

We predict that some readers of this paper will be more sympathetic to our diagnosis of American governance today—namely, that the constitutionality and the consequences of American governance are sub-par—than our proposed solution to the problem. Those readers might say: why not simply and immediately end the existence of the extra-constitutional functions of the administrative state today, and then let the current judicial system sort out the gaps and ambiguities of the law that remain? The answer to this question is twofold. First, too many people and groups have come to expect and depend on the kind of extensive federal regulation that is a feature of the American administrative state, and so the kind of root-and-branch extinction that the question contemplates is unrealistic. Second, Congress itself has become used to passing legislation that, once passed, intrinsically creates more questions and uncertainties. Our proposal preserves the public expectations created by the expansion of the American regulatory state. However, it also guides and disciplines the congressional legislative process in a way that encourages a gradual reduction in the kind of federal overreach we see today. It is, at minimum, a valuable thought experiment about how to restore constitutional norms. We think it becomes much more valuable to the extent that it becomes something more than a thought experiment. Justice Brandeis famously wrote, “The doctrine of the separation of powers was adopted by the Convention of 1787, not to promote efficiency but to preclude the exercise of arbitrary power. The purpose was not to avoid friction but, by means of the inevitable friction incident to the distribution of the governmental powers among three departments, to save the people from autocracy.”[15] A program of constitutional restoration would also have an array of positive effects, chiefly on Congress. It would encourage Congress to finish each job that it begins, rather than settling for the status quo: namely, avoiding hard policy questions by delegating them to policymaking agencies outside the legislature. It would restore the protections provided by an independent judiciary to litigants who are matched against the immense resources of the government. The administrative changes it implies would be difficult for the Congress and the president to avoid or reverse. A program of constitutional restoration would be a giant step forward for the vision of self-government expressed in the text at the very beginning of the Constitution.